By Mason B. Webb

During the whole of the Pacific campaign, no single mission was more difficult or challenging than the mission assigned to a unit of American GIs in New Guinea. With the Japanese Imperial Army poised to invade Australia from New Guinea, General Douglas MacArthur sent the untried 32nd Infantry “Red Arrow” Division—a composite of the Wisconsin and Michigan National Guard—to that island nation in September 1942 in a desperate effort to forestall the enemy invasion. It was an act that earned MacArthur the division’s undying hatred. What happened thereafter staggers the imagination.

Totally unprepared for war in the “green hell” of New Guinea, the Red Arrow boys were plunged into what one historian has called “some of the harshest terrain ever faced by land armies in the history of the war”—the steep, formidable, jungle-choked, disease-ridden, and unbearably hot and humid Owen Stanley mountain range that forms the crest of New Guinea. In The Ghost Mountain Boys: The Terrifying Battle for Buna—The Forgotten War of the South Pacific (Crown, New York, 2007, 384 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95), author James Campbell recounts the harrowing ordeal of the 32nd Division.

Totally unprepared for war in the “green hell” of New Guinea, the Red Arrow boys were plunged into what one historian has called “some of the harshest terrain ever faced by land armies in the history of the war”—the steep, formidable, jungle-choked, disease-ridden, and unbearably hot and humid Owen Stanley mountain range that forms the crest of New Guinea. In The Ghost Mountain Boys: The Terrifying Battle for Buna—The Forgotten War of the South Pacific (Crown, New York, 2007, 384 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95), author James Campbell recounts the harrowing ordeal of the 32nd Division.

While the six-month battle for nearby Guadalcanal was considered one of the most brutal battles ever fought, the battle for New Guinea was every bit as harsh—or worse. So difficult were the conditions that one 32nd Division veteran said, “If I owned New Guinea and I owned hell, I would live in hell and rent out New Guinea.”

Just getting to the enemy and closing with him required super-human effort. One soldier said, “In the beginning, we were all young, healthy GIs, eager to conquer the world … In a matter of weeks, long before we met the enemy force, all of us had been transformed into ghosts of our former selves.”

On New Guinea, the terrain rendered tanks and artillery useless. When men met the enemy it was often at point-blank range and at arm’s length, with the weapons being grenades, bayonets, even bare hands. The GIs did not even have insect repellent with which to keep the ferocious insects at bay.

Yet, despite the conditions and privations, the men of the 32nd Division managed to prevail —but just barely. The campaigns to take Buna and Sanananda cost the Red Arrows heavily; out of 11,000 men in the division’s three regimental combat teams, there were 9,688 casualties (over 7,000 due to disease—malaria, dengue fever, blackwater fever, dysentery, scrub typhus, hookworms, and more). Of the 131 officers and 3,040 enlisted men of the 126th Infantry Regiment who went into battle in November 1942, only 32 officers and 579 enlisted men were still standing by January 1943.

Campbell’s extraordinary, well-crafted story is made all the more vivid by the fact that he retraced the route taken by the Ghost Mountain Boys, something that no other author has ever done. He discovered a forbidding wilderness virtually unchanged during the past 60 years.

This book highlights one of the great untold stories of World War II and pays tribute to the extreme sacrifices of everyone who fought the battles of New Guinea.

The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine, by Michael Sturma, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2008, 232 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine, by Michael Sturma, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2008, 232 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

Following his gripping story of the loss of the submarine USS Harder (Death at a Distance, 2007), Michael Sturma has created another tale of tragedy below the waves.

On August 13, 1944, the USS Flier, on only its third war patrol, struck a mine in the Philippines’ Sulu Sea and began its fatal plunge. Only 14 men managed to escape, leaving the other 72 to their doom. Of these 14, six died in the water from exposure, wounds, fatigue, and other causes. After enduring 18 hours afloat, the eight remaining survivors were able to swim to Mantangule, a small nearby island that was crawling with enemy soldiers.

Like shipwrecked sailors over the centuries, the crew of the Flier found themselves confronted with a life-or-death challenge. Without food or drinking water, and with capture and instant death just a heartbeat away, the crew’s struggle to live had just begun. Using their last reserves of strength to escape to another island not occupied by the Japanese, the Americans were found and aided by local Philippine guerrillas, who were being supplied by Allied submarines in exchange for information and the safekeeping of stranded sailors.

The persistence and ingenuity of the handful of men in the face of overwhelming odds has all the elements of a classic World War II adventure—sudden disaster, physical deprivation, a ruthless enemy, friendly natives, and a dramatic escape behind enemy lines.

Sturma’s story of the Flier’s sinking and the survival of eight men sheds light on the nature of submarine warfare and naval protocol, demonstrating the high degree of cooperation that existed between submariners, coast watchers, and Philippine guerrillas. This is one book that is hard to put down.

Hitler, Dönitz, and the Baltic Sea: The Third Reich’s Last Hope, 1944-1945, by Howard D. Grier, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2007, 289 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Hitler, Dönitz, and the Baltic Sea: The Third Reich’s Last Hope, 1944-1945, by Howard D. Grier, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2007, 289 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Why Adolf Hitler, in the last days of the Third Reich, appointed Admiral Karl Dönitz to become Führer upon Hitler’s death has long been something of a mystery. With the publication of Grier’s Hitler, Dönitz, and the Baltic Sea, the mystery is solved.

In this, his first book, Grier, a professor of history at South Carolina’s Erskine College, persuasively argues that, far from being the deranged ideas of a madman, Hitler’s plan to win the war was actually well reasoned. Indeed, Hitler believed even until the final months of his regime that Germany could salvage victory from the jaws of impending defeat, with the maintaining of control of the Baltic Sea crucial to his plan.

The key to victory, Hitler and Dönitz believed, was a fleet of an entirely new class of U-boats that the Nazis were confident would sweep the seas of Allied ships, cut the supply lifeline and force Britain and the Soviet Union into starvation, and prevent additional American troops from reaching Europe.

To test the new submarines and train the crews, the Nazis needed to control the Baltic Sea and its ports. To launch their renewed U-boat offensive, the Germans also needed to maintain control of Norway, the only suitable location for U-boat pens following the loss of France in 1944.

But the new submarines came too late and in too few numbers to save the Third Reich. Hitler’s strategy to win the war by holding on to the Baltic failed.

The only disappointment is that the book contains just four photos, all of them of German Type XXI submarine U-3008. Disregarding that minor shortcoming, Hitler, Dönitz, and the Baltic Sea is a fascinating, well-written, and deeply researched book filled with important information that deserves to be more widely known and considered.

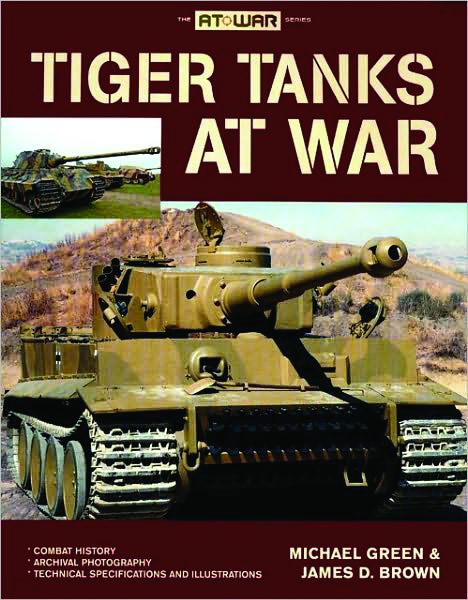

Tiger Tanks at War, by Michael Green and James D. Brown, Zenith, Osceola, Wisconsin, 2008, 128 pp., photographs, index, softcover, $19.95.

Tiger Tanks at War, by Michael Green and James D. Brown, Zenith, Osceola, Wisconsin, 2008, 128 pp., photographs, index, softcover, $19.95.

The Tiger tanks produced by Nazi Germany during World War II are legendary. As with all legends, however, there is as much myth as truth in their story. Part of the Tiger tank’s mystique originated during the war, when what little information the Germans gave out was exaggerated for propaganda purposes and to strike fear into the hearts of the enemy soldiers who would have to face these iron beasts.

Authors Green and Brown say that the truth lies somewhere between a machine that was considered almost impossible to knock out and one with plenty of vulnerabilities.

Tiger Tanks at War is filled with photos (scores of which are high-quality color views of restored tanks at museums and reenactments in the U.S. and Europe) that illustrate many points: the Tiger’s design and development, armament, armor, mechanics, operation, performance, strengths, weaknesses, and tactical employment.

Also included are numerous schematic drawings that show every detail of this famous panzer, plus text that spotlights some of Germany’s outstanding tankers as well as the vehicle’s successes and failures on the war’s far-flung battlefields. As an added bonus, there are also descriptive text and photos of American, British, and Soviet armor, and information about how Allied tanks and antitank weapons fared against the Germans.

Although not an exhaustive technical or detailed combat history of the Tiger tanks, the authors have done a fine job in providing the reader with a better understanding of how the vehicles and their crews actually functioned in combat. Anyone with an interest in armor will want Tiger Tanks at War on their bookshelf.

Order of Battle: German Panzers in WWII, by Chris Bishop, Zenith, Osceola, Wisconsin, 2008, 192 pp., photographs, maps, index, softcover, $19.95.

Order of Battle: German Panzers in WWII, by Chris Bishop, Zenith, Osceola, Wisconsin, 2008, 192 pp., photographs, maps, index, softcover, $19.95.

A superb companion piece to Tiger Tanks at War is Bishop’s detailed study of German armored formations deployed with devastating effect in all European, North African, and Mediterranean theaters during the whole of the war.

This lavish, graphic depiction of German armor is a rich compendium showing how the Panzerwaffe organizations worked and how armored warfare evolved from the stunning Blitzkrieg victories in 1939 and 1940 until Germany’s defeat in 1945.

The first entry in Zenith’s new “Order of Battle” series, Bishop’s book examines the organization and strength of the German tank forces that took part in each major German campaign, from the first thrust into Poland to the last-ditch gamble of the “Bulge” offensive in December 1944. Extensive coverage is also given to battles on the Eastern Front.

For each campaign, the author describes the panzer forces used, giving strength and orders of battle for the formations along with easily understood charts and 100 full-color detailed maps of the campaigns and battles.

Illustrated with over 150 photos of panzers in action, this dazzling, fact-filled book will appeal to both the scholar and military buff— and anyone with an interest in armored warfare, particularly its changing role in the German armed forces as the tide of war turned against them. Highly recommended.

Short Bursts

The Souvenir: A Daughter Discovers Her Father’s War, by Louise Steinman, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, California, 2008, 224 pp., bibliography, softcover, $15.95.

The Souvenir: A Daughter Discovers Her Father’s War, by Louise Steinman, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, California, 2008, 224 pp., bibliography, softcover, $15.95.

There seems to be a plethora of books recently by children of World War II veterans setting out to write about their fathers’ wartime experiences, experiences that their fathers were reluctant to write or even talk about. Many of these books were written by authors with a burning desire to honor their fathers’ memories but who lack the skills of a professional writer.

Within this genre comes The Souvenir: A Daughter Discovers Her Father’s War. Happily, the author’s abilities as a writer make this book a standout among the competition.

The “souvenir” in the title refers to a Japanese flag that her father, an enlisted man who served with the 25th Infantry Division, picked up somewhere on a battlefield and which the author decides to return to the fallen soldier’s family in Japan. Swinging expertly between her father’s letters to his wife, the historical record, and her own journey to follow her father’s footsteps back to the Pacific, Steinman has crafted a tremendously moving, poignant memoir of what war does to the human psyche and spirit.

Even if one has never heard of the battle for Balete Pass on the Philippine island of Luzon or has no interest in the Pacific Campaign, this is a book not to be missed.

U.S. Navy PBY Catalina Units of the Pacific War, by Louis B. Dorny, and U.S. Navy PBY Catalina Units of the Atlantic War, by Ragnar J. Ragnarsson, both from Osprey, Botley, Oxford, U.K., 2007, 96 pp. each, photographs, illustrations, index, softcover, $20.95.

U.S. Navy PBY Catalina Units of the Pacific War, by Louis B. Dorny, and U.S. Navy PBY Catalina Units of the Atlantic War, by Ragnar J. Ragnarsson, both from Osprey, Botley, Oxford, U.K., 2007, 96 pp. each, photographs, illustrations, index, softcover, $20.95.

For anyone with an interest in naval aviation, these two books fill a glaring hole in our knowledge of the aircraft of World War II. While much has been written about B-17s, B-24s, Corsairs, P-51s, P-38s, Thunderbolts, and the other so-called “glamorous” American warplanes, Consolidated Aircraft’s PBY Catalina flying boats have received short shrift when it comes to portraying their contributions to the war effort.

In fact, it is probably safe to say that many readers do not even consider the PBYs to be combat aircraft, so closely are they associated with reconnaissance and rescue missions and the guarding of convoys. Yet, the relatively slow and lumbering PBYs valiantly performed numerous combat missions—everything from being the very first U.S. Navy aircraft credited with shooting down an Imperial Japanese Navy Mitsubishi A6M Zero (on December 10, 1941) to bombing German U-boat wolfpacks.

As Dorny and Ragnarsson point out in their separate books, the PBYs were the unsung workhorses in both ocean campaigns, performing a variety of tasks in yeomanlike fashion. Besides providing a history of the development of seagoing aircraft, the authors describe many of the combat actions in which the PBYs were involved, and the wealth of photos and color illustrations depict the unit markings and other features in fine detail.

The Causes, Course and Outcomes of World War Two, by John Plowright, Palgrave, New York, 2007, 230 pp., maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

The Causes, Course and Outcomes of World War Two, by John Plowright, Palgrave, New York, 2007, 230 pp., maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

Anyone looking for a brief and readable history of World War II will be well advised to peruse this book by the former head of the history department at Britain’s Repton School.

Within its 230 pages, the book provides concise chapters dealing with a range of topics: the Versailles Conference of 1919 which effectively ended the Great War and planted the seeds for the next world war; Nazi foreign policy; appeasement by the French and British which emboldened Hitler; the fall of France; Britain facing Germany alone; the Eastern Front; the strategic bombing offensive against Germany; the Holocaust; the Pacific War; and the impact of the war on Great Britain, its empire, and the United States, and its role as a springboard toward the Cold War and today’s world situation.

Although these topics are well known to the majority of World War II buffs, Plowright’s cogent text will be welcomed by readers seeking a generalized coverage of the major issues.

King of the Oilers: The Story of the USS Chiwawa AO-68, by Jon L. Strupp, Beaver’s Pond Press, Edina, Minnesota, 2007, 166 pp., photographs, maps, softcover, $22.00.

Suffice it to say, there were no gas stations in the middle of the oceans where warships could stop and fill up. It is also safe to say that very few, if any, books have been written until now about America’s fleet of oilers, seagoing vessels whose mission it was to make sure that the battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, transports, and more had the fuel oil they needed to carry out their combat assignments.

Jon L. Strupp’s well-written and profusely illustrated book about his father’s ship, the USS Chiwawa (pronounced shee-wa-wa), which served in both the Atlantic and Pacific during the war, is a loving tribute to the ship, to the men who served aboard her, and to all of the millions of unsung men who toiled in anonymity to provide the logistical support without which the war could not have been won. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments