By Al Hemingway

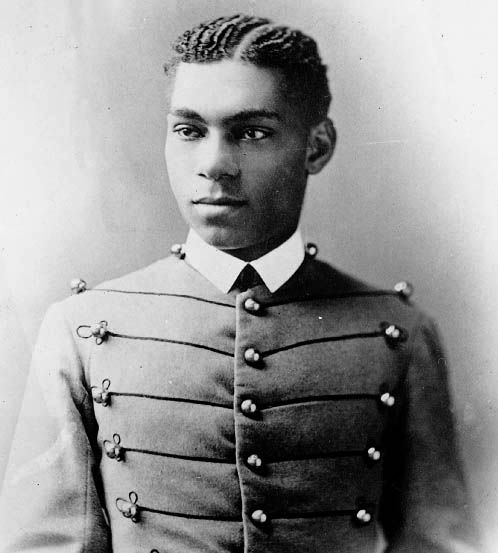

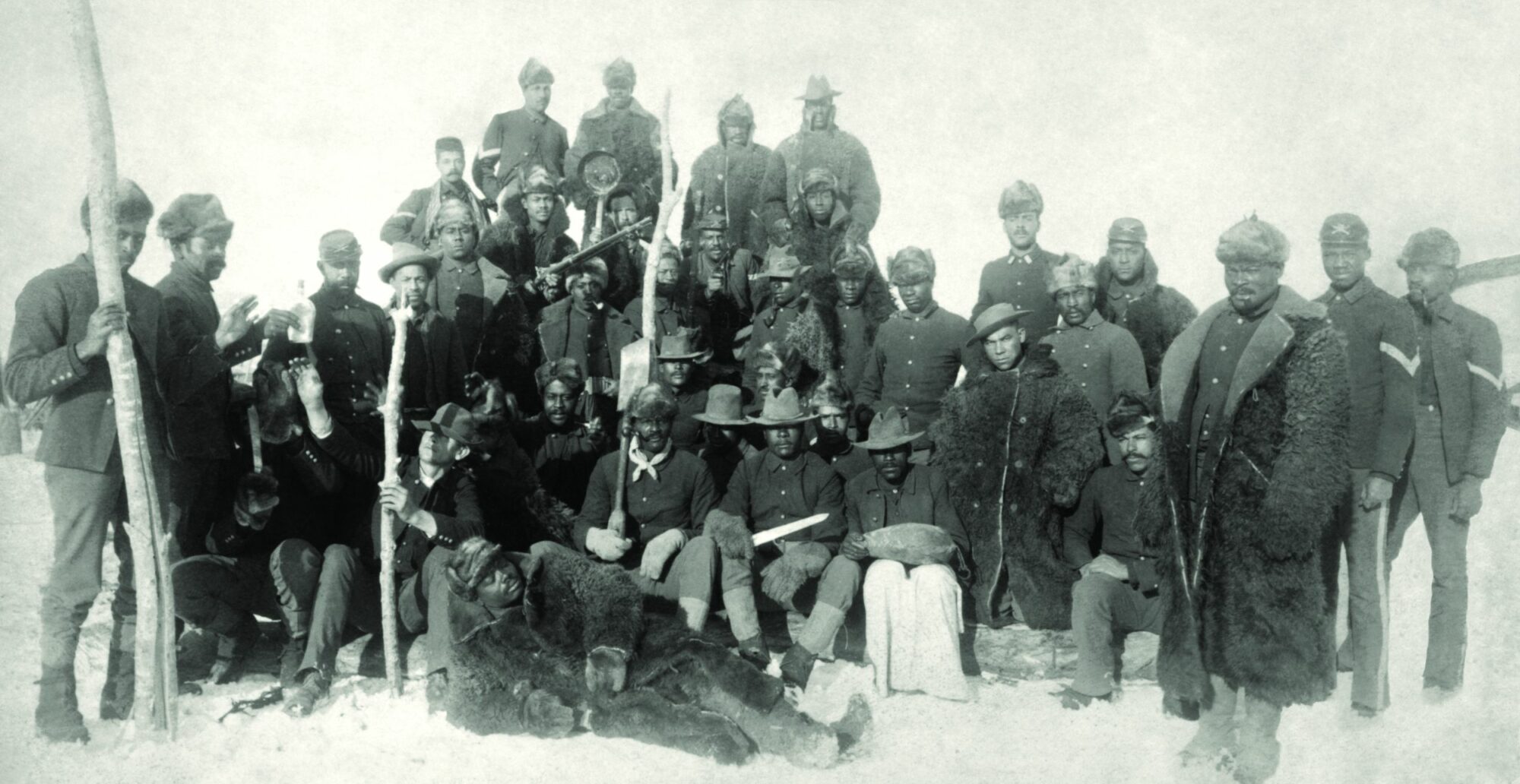

The case of Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper, the first African-American cadet to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point, is a fascinating if cautionary tale. Flipper endured bitter racial slurs and rejection by white cadets to complete his four-year term and receive his diploma in 1877, only to throw away his promising career a few years later on a mixture of love, carelessness and pride.

Flipper was assigned to the 10th Cavalry, one of four all-black regiments in the U.S. Army, and he was the first black officer to command troops in the field, assisting in the cavalry campaign against the Apache warrior Victorio in 1879. A bright, talented individual, Flipper served in several remote outposts in Texas and Oklahoma. At Fort Sill, in what was then Indian Territory, Flipper in his capacity as an engineer designed a series of drains to assist in the prevention of malaria, which was rampant in the region. It became known as “Flipper’s Ditch.”

Flipper was assigned to the 10th Cavalry, one of four all-black regiments in the U.S. Army, and he was the first black officer to command troops in the field, assisting in the cavalry campaign against the Apache warrior Victorio in 1879. A bright, talented individual, Flipper served in several remote outposts in Texas and Oklahoma. At Fort Sill, in what was then Indian Territory, Flipper in his capacity as an engineer designed a series of drains to assist in the prevention of malaria, which was rampant in the region. It became known as “Flipper’s Ditch.”

By all accounts, the young man born into slavery in Thomasville, Georgia, was slowly gaining the respect of his superiors and civilians he encountered. In 1880, he was named to the position of commissary officer at Fort Davis, Texas. Then the unthinkable occurred. Money was found to be missing from the post’s fund, and Flipper was charged with embezzlement and conduct unbecoming an officer. A court-martial convened in late 1881 and lasted nearly three months. In the end, Flipper was found not guilty of embezzlement but guilty of the other charge of conduct unbecoming. He was dismissed from the Army with a dishonorable discharge.

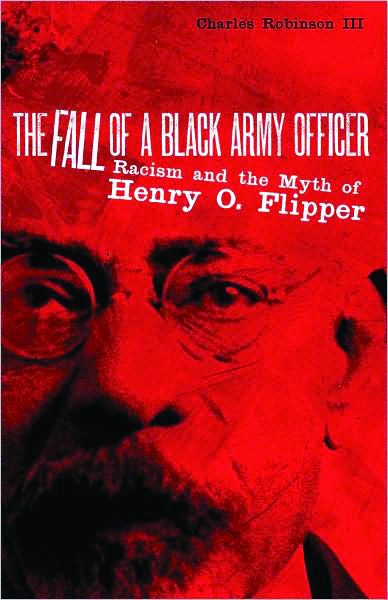

The question that author Charles M. Robinson III attempts to answer in his new book, The Fall of a Black Army Officer: Racism and the Myth of Henry O. Flipper (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2008, 197 pp., photos, index, notes, $29.95, hardcover), is how much of a role racism played in Flipper’s conviction and dismissal. To be sure, racism was prevalent at that time against black troops. Robinson contends, however, that it did not play a major part in the proceedings against Flipper. His new book shines much-needed light on the controversial issue of racial politics in our nation’s military.

Although something of a racist himself, Colonel William R. Shafter, Flipper’s commanding officer, believed that he was innocent. Flipper, however, mistakenly believed that Shafter was out to destroy him. He published a letter in the New York Globe claiming that Shafter had commented, “I got him where I want him.” Shafter, who typically allowed the mundane day-to-day duties to fall on his subordinates, was partially culpable for the missing money because of his neglect in not reexamining Flipper’s books while he was commissary officer. He was the final arbiter.

But if Flipper did not abscond with the funds, who did? According to Robinson, one of the prime suspects was Lucy Smith, his black servant, with whom he was rumored to be having an affair. Flipper never mentioned her in his subsequent memoirs, or in any of his numerous appeals. Robinson writes: “It is as though she ceased to exist. Yet Lucy, of all people, had the most access to the money in Flipper’s trunk. In spite of his protestations of caution, the evidence shows he was notoriously casual in letting her go through his things. If anyone stole the money, it was Lucy, either alone or together with any of the shadowy figures who, testimony revealed, apparently had routine access to Flipper’s quarters.”

But if Flipper did not abscond with the funds, who did? According to Robinson, one of the prime suspects was Lucy Smith, his black servant, with whom he was rumored to be having an affair. Flipper never mentioned her in his subsequent memoirs, or in any of his numerous appeals. Robinson writes: “It is as though she ceased to exist. Yet Lucy, of all people, had the most access to the money in Flipper’s trunk. In spite of his protestations of caution, the evidence shows he was notoriously casual in letting her go through his things. If anyone stole the money, it was Lucy, either alone or together with any of the shadowy figures who, testimony revealed, apparently had routine access to Flipper’s quarters.”

Ironically, the African American community at that time did little to promote Flipper’s innocence. He was a considered an elitist, even among his own race, and blacks simply ignored his numerous appeals for help. Robinson believes that the conviction was just, due to Flipper’s slipshod accounting methods. But he was no thief. Lucy Smith, with or without cohorts, probably stole the money, Robinson concludes.

“In successfully completing the program at West Point, and receiving his commission, Flipper did much to advance the cause of equality in the army,” Robinson writes. “In throwing it all away, he set the cause into slow motion, and it took decades to recover. In the end, his brief military career did more harm than good.”

Flipper unsuccessfully appealed his conviction for the rest of his life. In 1898, he attempted to reenlist in the Army during the Spanish-American War, but Congress refused to reinstate his commission. Late in life, he returned to Washington, D.C., as a special assistant to Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall, who ironically would be implicated in a scandal of his own—the Teapot Dome scandal of Republican President Warren G. Harding’s corrupt administration. Flipper, not part of the latter contretemps, died in New York City in 1940.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton granted Flipper a posthumous pardon, and the Army upgraded his discharge, more than a century after the fact, to “honorable.”

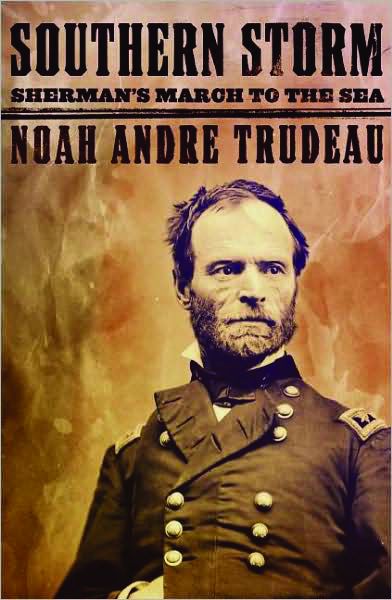

Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea by Noah Andre Trudeau, HarperCollins, New York, 2008, 671 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $35, hardcover

Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea by Noah Andre Trudeau, HarperCollins, New York, 2008, 671 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $35, hardcover

Following his successful Atlanta campaign from May to September 1864, Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman rested his war-weary army in the Georgia capital and contemplated his next move. Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s forces had evacuated Atlanta after a four-month siege and were now threatening Sherman’s supply lines from Chattanooga, Tennessee. Instead of chasing Hood, Sherman opted for a bold strategy. He split his army, sending Maj. Gen. George Thomas to confront Hood’s troops while he took his remaining 62,000-man contingent and marched 300 miles across Georgia to the port city of Savannah.

Sherman had several reasons for employing his men in this manner. He wanted to split the Confederacy and “smash things generally,” he said, including railway lines, food stock, horses, mules and other supplies and materiel. He also wanted to “demonstrate the vulnerability of the South” by destroying an area that “thus far [had been] spared war’s suffering.” Finally, as he conceded grimly, “I want to make Georgia howl.”

In his new book, Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea, longtime Civil War historian Noah Andre Trudeau has done considerable research on the celebrated—or infamous—March to the Sea. There is no doubt that Sherman’s troops did considerable damage in the Peach State, but the author has dispelled some of the common misconceptions of the campaign.

Sherman’s forces were divided into two corps. The left wing was led by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, the right by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Brig. Gen. Judson “Kill Cavalry” Kilpatrick’s mounted horsemen functioned as Sherman’s eyes and ears on the campaign. The two-pronged command cut a 60-mile-wide path of devastation as they made their way to the Atlantic coast. Soldiers tore up more than 200 miles of track, heating the iron rails and twisting them into what would become known as “Sherman’s hairpins.” Foraging parties confiscated food supplies from farms and houses they encountered along the march. These individuals became known, not always affectionately, as “bummers.”

Confederate President Jefferson Davis sent Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee to defend Georgia as the overall commander. Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith was put in charge of the state’s militia units, and Maj. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler commanded the southern cavalry, which some Georgia residents claimed stole as much from them as the Union troops did.

Although suffering from a disjointed command structure, the Confederates put up a determined defense, but nothing could stop the blue juggernaut. The only serious attempt at halting the advance was at the factory town of Griswoldville. Although the butternut defenders fought heroically, they suffered more than 650 dead and wounded before quitting the field. In the end, Hardee was forced to evacuate Savannah, which Sherman then offered to President Abraham Lincoln as a derisive “Christmas gift.”

Sherman estimated that his raid cost the South $100 million dollars in supplies. By January 1865, however, the rail line between Macon and Milledgeville was again operational. Even the telegraph service was up and running between Richmond and Mobile. “Ironically, from Sherman’s standard of values the March to the Sea was a failure,” writes Trudeau. “It was his hope to end the Civil War in such a way that the country would be able to turn back the clock to the idealized society that had (in his opinion) existed prior to the outbreak of the conflict. Political and social changes that he neither understood nor could control doomed that aspiration.”

There is no doubt that Sherman’s Savannah campaign had a profound psychological effect on the civilian population. Many had never even seen a Yankee this late in the war. But even if the Confederates had mounted a more effective effort to stop the blue-clad invaders, they probably could not have succeeded, Trudeau believes. “Sherman’s troops were simply too good and too experienced, their commander too fixed in his purpose,” he states.

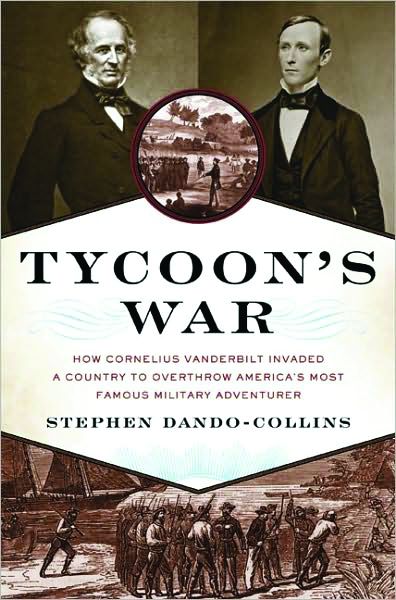

Tycoon’s War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America’s Most Famous Military Adventurer by Stephen Dando-Collins, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 372 pp., photos, index, notes, $26.00, hardcover.

Tycoon’s War: How Cornelius Vanderbilt Invaded a Country to Overthrow America’s Most Famous Military Adventurer by Stephen Dando-Collins, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 372 pp., photos, index, notes, $26.00, hardcover.

No one stood in the way of the loud, arrogant, and ruthless New York tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt. A descendant of Dutch immigrants, Vanderbilt had accumulated a huge fortune in the steamship business by means of often questionable tactics. In 1849, following the California gold rush, the tireless entrepreneur had a brainstorm: he would build a canal through Nicaragua to ferry people to the gold fields. He obtained a charter in Nicaragua for what he named the Accessory Transit Company and made improvements to the San Juan River, erecting docks on both coasts and even constructing a 12-mile-long road through the Central American jungle.

Vanderbilt turned over the company to Charles Morgan and Cornelius K. Garrison to manage in his absence. The wily pair basically stole the business out from under him by means of some underhanded stock deals. Vanderbilt, infuriated, swore that he would regain control of the company.

Meanwhile, William Walker, a Tennessee-born adventurer who had degrees in law and medicine, traveled to Nicaragua with 300 mercenaries to overthrow the government and put a halt to Vanderbilt’s scheme by teaming up with Morgan and Garrison. After several victories, Walker was declared president of the country in a trumped-up election in 1856, only to be run out office the following year. In the end, Vanderbilt got his revenge on his enemies, including Walker, who was executed by Honduran forces in 1860 while engaged in another filibustering mission.

Author Stephen Dando-Collins provides an insightful look at American history in this absorbing story of greed and power in 19th- century America, a story that spanned seven different countries. It demonstrates just how far Vanderbilt, hardnosed and calculating when it came to business, was willing to go to defeat anyone who stood in the way of his massive profits and power.

The Brusilov Offensive by Timothy C. Dowling, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 209 pp., notes, index, photos, $24.95.

The Brusilov Offensive by Timothy C. Dowling, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 209 pp., notes, index, photos, $24.95.

In The Brusilov Offensive, Timothy Dowling, a specialist in German and Russian history, provides a welcome new perspective on World War I and the fighting on the much-neglected Eastern Front.

Dowling goes into great detail to trace the 1916 Brusilov Offensive, named for Russian General Aleksei Brusilov, who masterminded the operation. The French had approached the Russians and requested their help in breaking the ongoing stalemate at Verdun. The Russian High Command responded by attacking the German Army along the Eastern Front, hoping that the bold maneuver would draw German troops away from the French lines. The subsequent offensive, unfortunately for the Allies, proved to be a disaster.

On June 4, Busilov’s campaign began with a huge but too short artillery barrage aimed at the Austro-Hungarian lines. In all, the Russians massed 40 infantry divisions and 15 cavalry divisions. The ensuing blitzkrieg tore through the opposing forces, and the Russians steamrolled more than 100 miles in some sectors.

As the months passed, however, Brusilov’s advance stalled. By late September, the attack had fizzled out completely and additional Russian soldiers had to be dispatched to Romania, where the Austro-Hungarian and German armies had successfully invaded. Despite the setback, Busilov was acclaimed a hero by his countrymen. His innovative tactics were watched closely by the Germans, who would put them to good (or bad) use in France in World War II.

American Rifle: A Biography by Alexander Rose, Delacorte Press, New York, 2008, 495 pp., notes, index, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

American Rifle: A Biography by Alexander Rose, Delacorte Press, New York, 2008, 495 pp., notes, index, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

When someone sits down to pen a biography, it is usually about the life of a prominent individual in history. Military historian Alexander Rose, however, has chosen a most unusual subject in terms of a biography—the American rifle.

From the minutemen at Concord and Lexington to the modern-day servicemen fighting the war on terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan, the rifle has been the mainstay of the American fighting man. Rose traces its beginnings to the Kentucky Rifle, a weapon that was difficult to load, but one that in the hands of a skilled woodsman was lethal at long distances. Many presidents were fascinated with firearms. George Washington wanted to be painted with a rifle in his official portrait. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln personally test fired various weapons on the White House lawn. Former Rough Rider Theodore Roosevelt, always an avid hunter, loved the Springfield Model 1903 bolt-action rifle.

The last chapter in the book is of particular interest. Rose feels that “we are reaching the beginning of the end in terms of current rifle development.” Experts are predicting that by the year 2010, newer developments are on the horizon for “the next generation of small arms.”

The Pirate’s Pact: The Secret Alliance Between History’s Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America by Douglas R. Burgess, Jr., McGraw Hill, New York, 2008, 288 pp., notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

The Pirate’s Pact: The Secret Alliance Between History’s Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America by Douglas R. Burgess, Jr., McGraw Hill, New York, 2008, 288 pp., notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Pirates are typically viewed as barbaric cutthroats with little regard for governments or laws. Images of swashbuckling movie star Errol Flynn immediately come to mind.

Author Douglas Burgess, however, paints a more complex picture of pirates. With the growth of North America, England’s relationship with her corsairs was transferred to the colonies. The colonial governors, Burgess notes, enjoyed a “widespread collusion” with the bawdy group. Some pirates were given commissions by benevolent administrators, offered safe havens and presented monetary awards by some of the colonies’ richest families. “Pirates, I discovered, could be both enemies of the state and, simultaneously, allies of its colonial administration,” Burgess writes.

As England attempted to rid the world of this scourge, her own colonies were aiding and abetting them. Burgess delves into the “golden age of piracy” that lasted from 1660 to 1725, an era that has long been misunderstood in the sweep of our nation’s history.

Merchant Mariners at War: An Oral History of World War II by George J. Billy and Christine M. Billy, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2008, 324 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $30.00, hardcover.

Merchant Mariners at War: An Oral History of World War II by George J. Billy and Christine M. Billy, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2008, 324 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $30.00, hardcover.

“An army travels on its stomach,” Napoleon famously declared. However, long before he uttered his notable quote, other military leaders had recognized the importance of supplies for their troops. If an army were to win on the battlefield, it was imperative that the men be well-equipped, well-armed and well-fed.

During World War II, the U.S. Merchant Marines provided just such a service, often through dangerous waters where German and Japanese vessels lurked, ever ready to send the supply ships to the bottom of the ocean. The authors, a father-daughter team, have collected numerous interviews from former graduates of the Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York.

Liberty Ships, the mainstay of the merchant fleet, “became the workhorses of the American merchant marine,” they write. An amazing 2,700 of the vessels were constructed, some in as little as 40 days. By war’s end, 200 of these ships had been sunk—an astonishing 50 of them on their first voyage. Merchant mariners numbered over 200,000 during the conflict, and 7,000 were killed. Of that total, 142 were midshipmen who never lived to see their graduation from the United States Naval Academy.

This collection of personal vignettes offers the reader a rare glimpse into the training and subsequent duty aboard a ship traversing perilous seas to deliver much-needed supplies to America’s fighting men.

Philip II of Macedonia by Ian Worthington, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2008, 304 pp., index, notes, illustrations, $35.00, hardcover.

Philip II of Macedonia by Ian Worthington, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2008, 304 pp., index, notes, illustrations, $35.00, hardcover.

Although much has been written about Alexander the Great, the accomplishments of his father, Philip II, have been largely ignored. Ian Worthington has set out to correct that imbalance.

While a prisoner of the Greeks for three years, Philip watched with great interest how they trained their soldiers and employed them during battle. When he was freed from captivity, Philip took what he learned and set about making the Macedonian army one of the most feared at that time. He developed the sarissa, an 18-foot spear, for his men. This terrifying weapon could run a man through at an incredible distance of 20 feet. When the rear ranks of the phalanx held them skyward, they obstructed the enemy’s view of their troop movements.

A military genius, Philip was also an astute politician. He used tact and diplomacy when dealing with his rivals, rather than engaging them in a mutually costly war. By his sheer determination and will, he carved a vast Macedonian empire. At the time of his death in 336 bc, he had conquered northern Greece, southern Yugoslavia, most of Albania and Bulgaria, and all of Turkey.

“Philip saved Macedonia in its hour of need,” writes Worthington, a history professor at the University of Missouri-Columbia, “and in forging what would be the first nation-state in Europe he created a first-class army that became the best in the Greek world, united his kingdom, stimulated the economy and laid the foundations of what would become the vast Macedonian empire under Alexander.”

Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization by Cathal J. Nolan, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2008, 607 pp., index, maps, $149.95, hardcover.

Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization by Cathal J. Nolan, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2008, 607 pp., index, maps, $149.95, hardcover.

Although admittedly expensive, this new encyclopedia of the wars of Louis XIV is a beautifully done reference book for those researching or merely intrigued by a notably colorful period of European history.

Author Cathal Nolan has included more than 1,000 entries defining military technology, appropriations for war, the social order of the day and the “evolution of professional standards for the new armies and navies of the post-1650 world.” He has also added brief profiles of important leaders and figures of the era. Significant battles, wars, and sieges are described in exact detail, as well as lesser-known skirmishes which, although did not decide an outcome of a conflict, added a new dimension to the fighting.

Wars of the Age of Louis XIV is an impressive attempt to understand the complex historical character who became the “Sun King” of France. Although arrogant at times, Louis led France to become the unsurpassed military power on the European continent under his reign. In the end, his quest for territorial gain would impose a heavy burden on the country. On his deathbed at the age of 77, Louis muttered to his great-grandson: “Try to remain at peace with your neighbors. I loved war too much.”

Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare by R.G. Grant, DK Publishing, New York, 2008, 360 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $40.00, hardcover.

Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare by R.G. Grant, DK Publishing, New York, 2008, 360 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $40.00, hardcover.

Around the year 2450 bc, an Egyptian force ferried across the Nile delta to attack an enemy in present-day Lebanon and Palestine. This amphibious assault was the first recorded instance of combatants utilizing a warship to confront a foe. From that primitive beginning to the massive warships and super carriers of today’s navies, the author traces the history of naval warfare.

This coffee table-size book is crammed with numerous photographs, maps and descriptions of the ships, armament, equipment below decks and other auxiliary apparatus necessary in the smooth operation of a naval warship. Grant covers many of the clashes at sea among France, Spain, Holland and Great Britain. On the American side, he describes the battles of Mobile Bay, Vicksburg, and Hampton Roads in the Civil War. He also writes about the emergence of the U.S. Navy as a force to be reckoned with on the high seas during the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II and the First Gulf War.

From ancient galleys to the high-tech world of today’s ships, the author does a marvelous job of entertaining and informing the reader.

Medieval Warfare: The Rise and Fall of English Supremacy at Arms, 1314-1485 by Peter Reid, Running Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 561 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $15.95, softcover.

Medieval Warfare: The Rise and Fall of English Supremacy at Arms, 1314-1485 by Peter Reid, Running Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 561 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $15.95, softcover.

Peter Reid, a retired major general in the British Army, has written a captivating tale of waging war during the14th and 15th centuries in England, Scotland, and France. Not only does he go into remarkable detail on the battles of Agincourt, Poitiers, Crecy, and Calais, he also describes how these campaigns were financed and supplied, how armies were raised, and what strategies were used at the time.

Although the king was a powerful entity, he still needed to obtain the approval of Parliament to enter hostilities with an adversary. The governing body was comprised of the educated class and had enormous power when the issue involved the cities and hamlets of the country. Power was inevitably divided.

There were also two separate armies during that period. The first was a general army, which consisted of semi-trained soldiers who were ordered to arms during the clashes along the Scottish border and other internal threats to the security of England. The selective army, recruited to fight overseas, was better-equipped and possessed much better weapons and supplies. Medieval Warfare details how the English, by dividing their forces and duties, enjoyed unparalleled dominance over France and Scotland. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments