By Charles Whiting

Adolf Hitler loved children. Before the war consumed all his energies he entertained children at his holiday home on the “mountain” all the time. Over the years, his court photographer, Professor Heinrich Hoffmann, filled whole albums with pictures of the Master and children.

Naturally, it is clear, they had to be blond and smile winningly when he took their hands for a walk, bent down to talk to the very small ones, and patted their bright yellow hair. Although the Master and most of his admiring court were dark-haired, their ideal was the blond Aryan race.

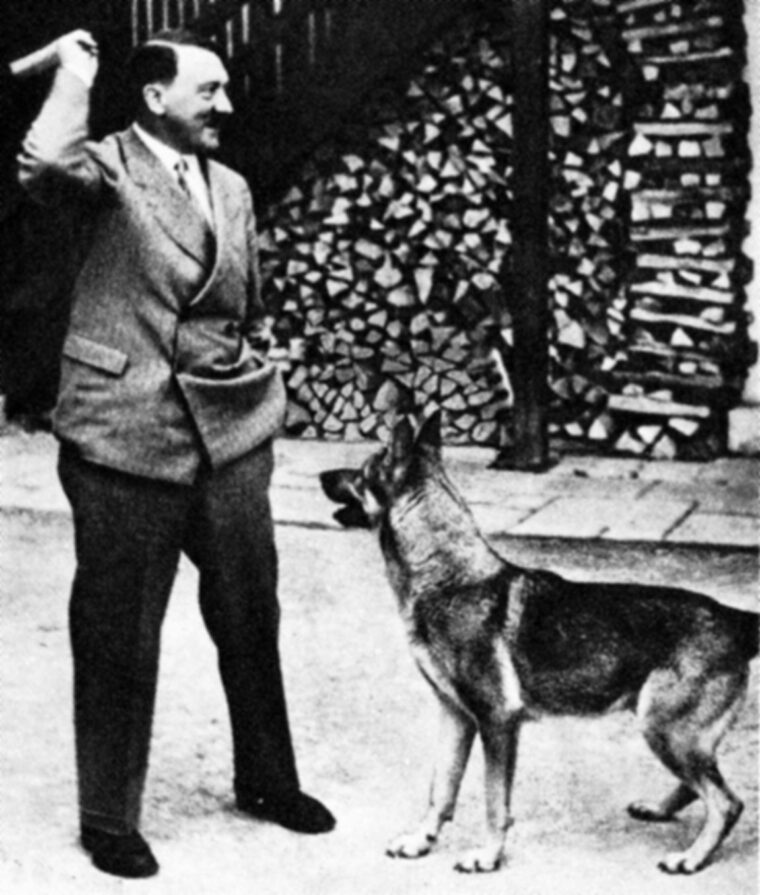

He loved dogs, too, especially German shepherds. Some of his court maintained that he loved dogs more than he did human beings. Even at the height of his power when he ruled virtually all of Europe from North Africa to Norway and from the English Channel to the Caucasus, he personally trained his own dogs. The most powerful man on the Continent apparently did not find it demeaning to be seen running in front of one of his puppies, carrying a stick in his mouth to demonstrate to the young dog how it should carry such an object.

Indeed, despite his status as one of the four most powerful men in the world, he remained the simple man of the people. He slept on a spartan cot, not much better than those of his soldiers. He wore a white cotton nightshirt, used a chamber pot for his needs during the night, and when it was very cold on the mountain, he donned an old-fashioned nightcap to keep his head warm.

He abhorred strong waters, but on occasion he might drink a glass of champagne or on hot days a beer. It was the same with food. Again, he did not indulge in the rich foods and exotic foreign dishes that many in his exalted position enjoyed. Instead, he was a vegetarian, sticking to the homely vegetables grown in his own greenhouses on the mountain—carrots, peas, leeks and the like. But if forced, he would eat a stew made with the cheapest cuts of meat or a slice of ham cut straight from the shank in the peasant fashion.

An Obsession With Health

Some said he had sexual problems. Malicious tongues maintained he was inadequate both physically and psychologically. But he had at least two known mistresses, and the servants who spied on him and his last mistress, Eva Braun, on the mountain and examined their bed in the morning after they had slept there always stated they had evidence enough from the sheets to prove the relationship was perfectly normal.

Those who saw the Master naked testified he was quite adequate in the nether region. When the Master went on picnics from the mountain, one of his greatest pleasures, he would urinate against the trees with the rest of the male entourage, who were naturally interested in the Master’s physical endowments. None of them ever reported that he was lacking in that quarter.

It was noted, however, that he worried greatly about his own health—he was something of a hypochondriac. He suffered from dizziness, flatulence, gastric and chest pains, neck pustules, and restrictive palsy, and, in the end, was taking up to 60 pills a day. At the same time, he was also very concerned about the health of his subjects.

The result was that he instituted measures that are strangely contemporary. He introduced cancer registries, the first to note new cases of the disease (incidence and not just fatal cases as was customary in other countries). Pesticides containing arsenic, which can cause cancer, were banned. Naturally, smoking was frowned upon, and Germany was the first to introduce antismoking campaigns.

The Master’s ideology promoted diets with less sugar, fat, and meat and fewer canned foods. By law, that great German staple, bread, had to contain a minimum percentage of whole grain flour. Lead-lined toothpaste tubes were banned. Hitler was basically vegetarian, as was his SS chief, Heinrich Himmler, who even had his own vegetable garden.

By 1941, the hazards of smoking were taught in schools, and 60 cities were banning smoking in their public transport systems. One year later, in the midst of total war, the Master was worrying about whales, writing, “The increasing consumption of whale oil is diminishing the population of whales.” How environmentally friendly can you get?

A Man of Extreme Contradictions

What can one make of such a man, so modern in his thinking, embodying in many ways the traits that we are taught to admire in our own time—the vegetarian, who instituted campaigns against radiation hazards and tobacco (Hitler’s Germany had the world’s first Institute of “Tobacco Hazards Research” at the University of Jena); who used his state offices and research facilities to protect the national “germ plasma,” the forerunner of our own genetic heritage?

Was this the same man who forced a great war on Europe, which resulted in some 30 million deaths? Could this lover of dogs and young blond children really institute a wave of mass anti-Semitism, which ended in the Holocaust? How could Hitler, who abhorred hunting and criticized his own followers, in particular Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, for indulging in the shooting of birds and the killing of wild pigs, ship off men, women, and children by the thousands, and in the end by the hundreds of thousands, to be liquidated in the ovens of his concentration camps?

Could such forward-looking, benevolent modernity go hand in hand with this medieval, almost pathological cruelty? In the case of Adolf Hitler, the new master of Germany since 1933, it could. And it is, in reality, not all that difficult to comprehend. Hitler, like so many of his generation, had been brutalized by four years in the trenches in World War I. Wounded and temporarily blinded in that war, he was released from a beaten German Army, which had been his first real home, into a chaotic new German Republic. Like so many others of that “Front Generation” the “stubble-hoppers,” as they called themselves, he felt he had been betrayed by the Socialists and the Jewish plutocrats he believed now ran this new decadent Germany.

Thus, it was while he absorbed the new ideas current in the 1920s (and it must be remembered that the Germany of that time was a forerunner of modernity in virtually every field), that Hitler and many others fell back into the cruel culture of an older Germany. By the time Hitler and his followers came to power, there was a kind of polarity of two extremes that many foreigners found puzzling, and then repelling. How could the Nazi guards in concentration camps give some of the kids in their charge a typical German Christmas, filled with all its sentimentality and kitsch, and then consign those same children to the ovens a day or so later?

The Bourgeois Berghof

It was little different when Hitler built his holiday home in the Bavarian Alps, which later became the site of his court. Haus Wachenfeld, later called the Berghof after Hitler remodeled it, was a bizarre blend of the grandiose—a natural stage set for one of Wagner’s pompous operas—and the mundane. Its great windows provided breathtaking panoramic views of the surrounding peaks. But its architecture was Bavarian suburban: checked tablecloths, wooden chairs with hearts carved in them, pewter plates and drinking mugs on the shelves. The décor might have been lavish, but the overall effect was not palatial but bourgeois.

At the Berghof where his court was mostly held, the Führer’s lifestyle was similarly contradictory. There he might receive famous politicians, heads of state, even an ex-king of Britain; yet between affairs of state, Hitler’s days at the Berghof were a monotonous round of boring meals, silly Hollywood movies (the Master’s favorites were Charles Laughton in The Private Life of Henry VIII and Gary Cooper in The Lives of a Bengal Lancer) and tedious hour-long monologues.

“Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler”

But there was another secret side to Adolf Hitler, discovered in 2003. Back in 1943, General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), commissioned a top secret report on Hitler. Thirty copies of the report compiled by Dr. Henry Murray were found at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, nearly 60 years later.

The report was titled “Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler.” Murray presents a picture of Hitler different from the kind, simple dog-loving persona that he presented to the prewar world. Based on psychoanalysis and statements of Hitler’s former intimates such as “Putzi” Hanfstaengl and Otto Strasser, who had fled to the United States, Murray stated that Hitler suffered from neurosis, hysteria, paranoia, oedipal tendencies, and schizophrenia.

Two years before Hitler’s suicide Murray concluded with amazing foresight, “There is a powerful compulsion in him to sacrifice himself and all of Germany to the revengeful annihilation of Western culture, to die, dragging all of Europe with him into the abyss.”

Murray speculated that Hitler might arrange for himself to be assassinated or would retreat to his bunker and shoot himself. The German generals’ plot to assassinate Hitler in July 1944 failed. In the end Hitler, as is well known, committed suicide in 1945. Murray’s task was also to propose ways of “converting the Germans into a peace-loving nation” after the war. He does not disguise his belief that the German people shared Hitler’s guilt. He wrote, “This demi-god almost exactly met the needs, longings and sentiments of the majority of Germans.”

Adolf Hitler and “The Mountain People”

This was the Master, who assembled a kind of Nazi Mafia around him on the mountain. In due course, he and they would conquer most of Europe from the English Channel to the Ural Mountains. Their soldiers would achieve tremendous victories, fighting the British, the Americans, the Russians, and a score of smaller nations. In an indirect way, they would break the British, French, and Dutch empires and start the Cold War, from which the United States would emerge as the world superpower. But this Nazi Mafia, “The Mountain People” as they called themselves, dominated by the megalomaniac Hitler, remained essentially a group of second-rate toadies. Once Hitler was dead, his followers melted away as if they had never existed.

The late Charles Whiting was himself a veteran of World War II and, subsequently, the author of numerous acclaimed books on the subject.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments