By Mason B. Webb

In the West, the Soviet Union’s contributions to the Allied victory over the Third Reich are generally unknown or underappreciated. While a variety of reasons contribute to this lack of knowledge or appreciation, it must be acknowledged that the Soviets suffered greatly (an estimated death toll of 20 million Soviet civilians and military) and fought heroically against the German invaders long before any American troops set foot on the European continent.

Indeed, it is accurate to say that, had Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union not prevailed against Adolf Hitler’s Germany and decimated the enemy’s forces on the Eastern Front, the U.S. and Britain would not have enjoyed the successes they did from 1943 to 1945. Hitler might even have won the war.

We recently received four new books that go a long way in providing Western readers with a clearer picture of the immense role played by the Soviet Union.

In Master of the House: Stalin and His Inner Circle (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 313 pp., 2009, bibliography, index, hardcover, $38.00), author Oleg V. Khlevniuk, a senior research fellow at the State Archive of the Russian Federation and a renowned expert on the life of Josef Stalin, goes behind the curtain to reveal the secret workings of the dictatorship.

Using previously unavailable documents from the Soviet archives, Khlevniuk focuses on the top organ in Soviet Russia’s political hierarchy—the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (“Politburo”)—and on the political and interpersonal dynamics that weakened its collective leadership and led to Stalin’s rise to supreme dictator.

Khlevniuk challenges the existing theories and assumptions on the workings of the Politburo, uncovering along the way new information about Stalin’s previously hidden political machinations.

A thoughtful, well-researched, scholarly, yet very readable work that goes far to explain much and give the reader a solid grounding in Soviet-style wartime politics. Translation work is by Nore Seligman Favorov.

In The Korsun Pocket: The Encirclement and Breakout of a German Army in the East, 1944 (Casemate, Philadelphia, 2008, 374 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95), Swedish authors Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson have crafted a superb and highly detailed study of Germany’s second Stalingrad—the defeat of another enemy army.

In January 1944, six divisions of Army Group South found themselves surrounded following a massive counteroffensive mounted by the 1st and 2nd Ukranian Fronts of the Red Army. As Stalin ordered his forces in for a battle of annihilation, the wily German commander, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, took steps to extricate the trapped divisions without waiting for Hitler’s approval. But his efforts then bogged down due to the fierce winter and even stiffer Soviet resolve. It appeared that the men in the pocket were doomed.

Low on supplies, an airdrop of food and ammunition not nearly enough to sustain life and combat effectiveness, the surrounded German units decided to try a last-ditch effort—an explosive breakout, led by the 5th SS Division Wiking. Incredibly, the escape was mostly successful, with the Germans able to squeeze out of the pocket but forced to leave behind most of their wounded and heavy weapons.

The Korsun Pocket is a well-written, fast-paced chronicle of what desperate men facing certain death are capable of achieving.

In Marshal Zhukov at the Oder: The Decisive Battle for Berlin (Sutton Publishing, Chalford, UK, 2008, 308 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $37.95), author Tony Le Tissier provides readers with a brilliant analysis of what Soviet armies were doing in the East while British and U.S. forces were heading eastward during the opening weeks of 1945.

While still recovering from the shock of the German counteroffensive known as the Battle of the Bulge, the Americans found themselves stuck trying to break through German resistance along the Siegfried Line and in the Hürtgen Forest. On the other front, however, the Red Army was having better success; Stalin expected that Zhukov’s armies, less than 50 miles from Berlin, would soon be sweeping into Berlin and bringing about a swift conclusion to the war.

Meanwhile, however, the Soviets ran into a solid wall of incredibly fierce resistance—much of it conducted by boys and old men and the remnants of battered German divisions—who knew that they were the last line of defense and the only ones who could prevent an early collapse of the Fatherland.

For two months a bloody stalemate took place on the Eastern Front until the Soviet bridgeheads north and south of the German fortress at Küstrin were united and the resistance overcome. Next came the bloody April battles for the Seelöw Heights, the last line of defense to the east of Berlin. Once this strategic position was wiped out, the road to the German capital was clear.

Le Tessier, a British author with several books about the battle for Berlin to his credit, has drawn upon considerable material not previously available to construct in spellbinding fashion the final months leading up to the end of the Third Reich.

Vladimir Yakubov and Richard Worth have combined their considerable knowledge and talents to bring us a history of a little-known aspect of the Soviet military machine, the navy. In Raising the Red Banner: The Pictorial History of Stalin’s Fleet, 1920-1945 (Spellmount Publishers, Chalford, UK, 2008, 224 pp., photographs, hardcover, $39.95), readers are finally given a look at this little-known subject.

Yakubov, a Russian-born U.S. Navy veteran, and Worth, author of the acclaimed Fleets of World War II, tell the neglected story of the impressive but troubled growth of the Soviet Navy, the obsolete collection of the Czar’s warships inherited after the 1917 revolution, an event that led to Russia’s capitulation and takeover by Communist leaders.

With scores of photos and charts and chapters on battleships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and other surface vessels, plus ordnance data and major supporting units, this is the first book to cover in detail the history and composition of the Red Navy. Extremely valuable for anyone wanting authoritative naval information about one of WWII’s major combatants.

All four of these books are recommended.

Two recently published books by sons of men who served on U.S. Navy attack transports explore the role of two ATs in World War II—but in entirely different ways. The Lady Gangster: A Sailor’s Memoir, by Del Staecker (Cable Publishing, Brule, WI, 2009, 172 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $23.95), and Attack Transport: USS Charles Carroll in World War II, by Kenneth H. Goldman (University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2008, 320 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.00), offer revealing perspectives of life aboard wartime attack transports.

ATs were the unsung naval heroes of the war and, for the most part, they are all but forgotten today except by their aging crews, the combat troops who sailed on them, and the families of the veterans.

This lack of recognition is curious for, after all, attack transports were needed to ferry vast numbers of troops across thousands of miles of ocean in order to engage enemy forces holed up on islands and foreign shores.

But ATs were more than just passenger ships; they often found themselves under fire by enemy submarines, surface vessels, and aircraft, and frequently had to battle for their lives—and the lives of the men on board. It was a dirty, dangerous business with little of the glamour associated with cruisers, carriers, battleships, and the like.

Staecker’s book is a combination of his father’s memoirs as a sailor aboard the USS Fuller, called both “The Lady Gangster” because many of her crew were from Chicago and the “Queen of the Attack Transports,” and the unique way he got his father to finally open up and talk about his wartime experiences. As such, the book puts Irvin Staecker front and center.

Goldman’s book, on the other hand, admittedly subordinates the role played by his father, Robert, in telling the story of the “Lucky Chuck.” Goldman, a Hollywood scriptwriter, does supplement excerpts from his father’s wartime diary and letters home with those of other crew members to capture the boredom, fears, excitement, and humor shared by sailors aboard any ship at war. Anecdotes and memories collected from a number of interviews give Attack Transport an immediacy lacking in many operational histories.

Staecker’s book grew out of an 18-hour father-son car trip in 1967 from Florida to Illinois with a broken car radio. The two had been making uncomfortable small talk until the son (Del) asked, “Dad, will you tell me what you did in the war?”

The father’s answer is the firsthand account of the Fuller and its courageous crew who braved enemy attacks while delivering troops and supplies during many of the toughest battles in the South Pacific. It is also the poignant tale of how a simple question forged a lasting bond between father and son.

Both books have a charm all their own and get two thumbs up.

Dawn of D-Day: These Men Were There, June 6, 1944, by David Howarth (Skyhorse Publishing, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 255 pp., photographs, maps, softcover, $14.95).

Dawn of D-Day: These Men Were There, June 6, 1944, by David Howarth (Skyhorse Publishing, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 255 pp., photographs, maps, softcover, $14.95).

Before his death in 1991, David Howarth was one of Britain’s finest and most prolific chroniclers of World War II, and Dawn of D-Day, a republishing of his 1959 classic, D-Day, The Sixth of June 1944, is arguably Howarth’s finest book.

In it, he brilliantly breaks down all the facets of the immensely huge and complex Operation Overlord into easily read chapters that never fail to capture the broad scope of the plan while focusing on the derring-do of the men who were called upon to carry it out.

Howarth had a fine gift for descriptive narration. For example, he writes that a platoon of 82nd Airborne troopers were on their way to capture a key bridge: “At last, [James R.] Blue thought, things were getting interesting. This is what he had come for. Then he saw his first German. A motorcycle and sidecar came up from the bridge, and the rider did not seem to see the parachutists before it was too late to stop. He came on, and succeeded in passing all forty riflemen at point blank range, because none of them could fire without risk of hitting their friends on the opposite side of the road. He nearly got through with his life, but not quite. The machine gunner shot him in the back as he rode away towards Sainte-Mère-Eglise, and the motor bike crashed into the hedge. It was terribly easy.”

From the early planning stages of Operation Overlord to the moments when it became clear that the Allies’ great gamble had succeeded, Howarth captured it all. It is a shame that he is no longer with us.

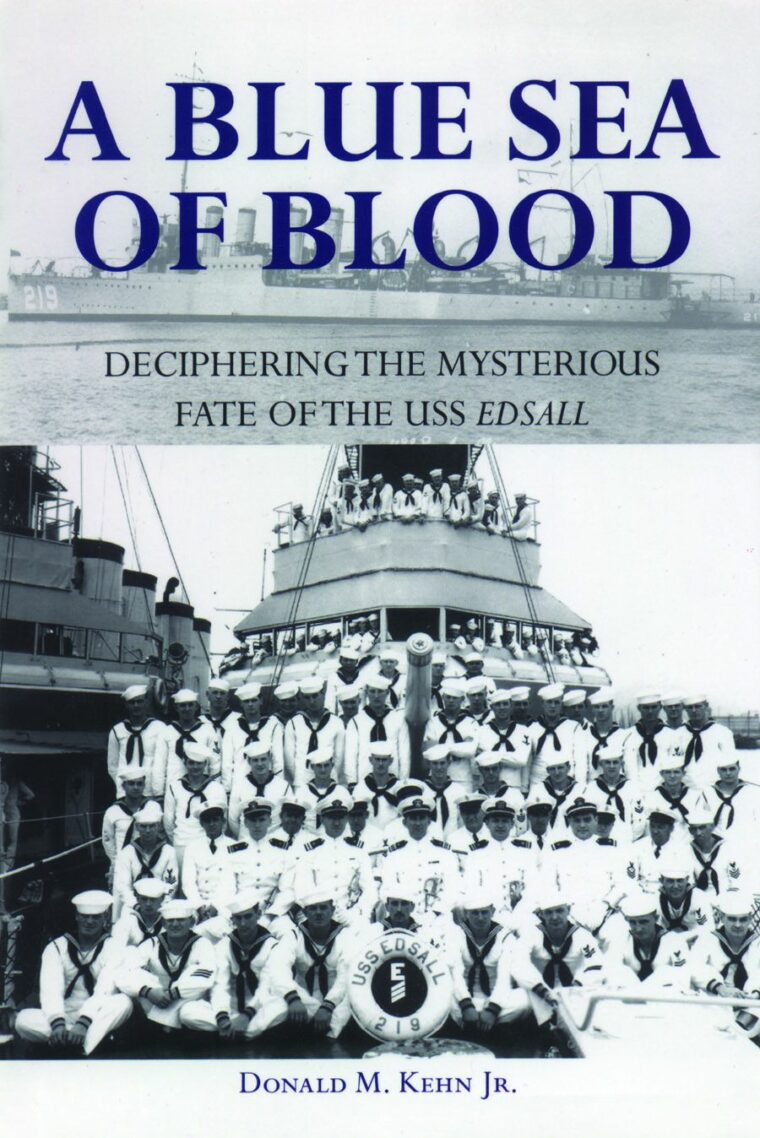

A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall, by Donald M. Kehn, Jr., Zenith Press, New York, 2008, 286 p., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $26.00.

A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall, by Donald M. Kehn, Jr., Zenith Press, New York, 2008, 286 p., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $26.00.

At 6 pm on March 1, 1942, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Edsall (DD-219) and fuel ship USS Pecos (AO-6) came under fire by Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft from a task force operating in the Indian Ocean, some 360 miles south of the American naval base at Tjilitjap, Java.

In A Blue Sea of Blood, his first book, author Kehn does a masterful detective job in delving into long-sealed Japanese records, previously unknown material from crewmembers’ families, and U.S., Dutch, and Japanese documents to reveal, as completely as possible, what happened to the Edsall and her crew.

After detailing Edsall’s prewar service in the 1920s, Kehn explores her brief but heroic World War II actions. For example, on January 20, 1942, she became the first U.S. destroyer to participate in the sinking of a full-sized enemy submarine (I-124) in World War II.

While performing convoy escort duty in late February 1942, Edsall, along with the destroyer Whipple and the seaplane tender Langley, were attacked by a swarm of Japanese Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers. Langley was so badly damaged that she was abandoned. Edsall rescued 177 survivors; another 308 were saved by Whipple. After transferring her load of survivors to Pecos off Christmas Island, Edsall sailed for Tjilitjap but was attacked by surface ships and dive-bombers during the Battle of the Java Sea and sunk.

A handful of Edsall survivors were picked up by Japanese vessels and incarcerated in POW camps; all later died in captivity. In 1952, five headless skeletal remains of Edsall crewmembers were found in a grave in present-day Indonesia, indicating that they had been beheaded by their captors.

In this detailed, comprehensive look at a doomed ship and her dutiful crew, Kehn examines how the Edsall was used by both sides in their propaganda efforts and how her heroic service and final battle were relegated to obscurity in naval histories.

The U.S. lost 71 destroyers in World War II. Most of them, sadly, have been forgotten by all but the aging veterans who once served on them or their family members. With the publication of the riveting A Blue Sea of Blood, it is unlikely that the Edsall and her crew will be forgotten any time soon.

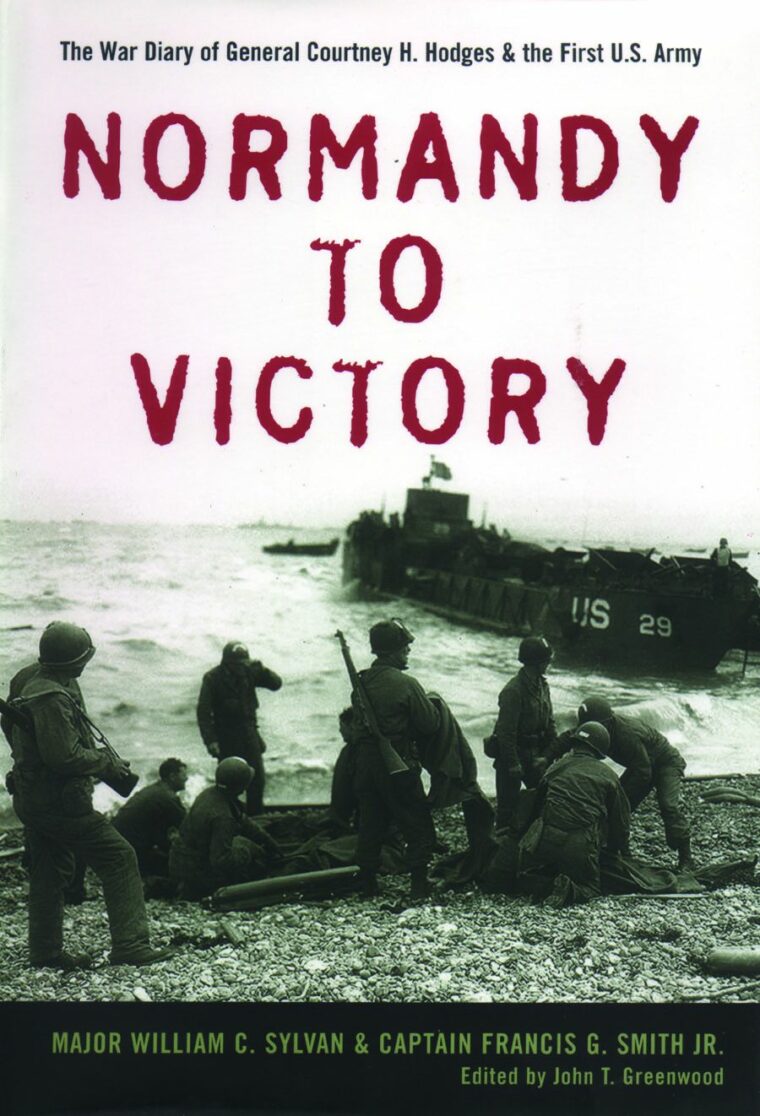

Normandy to Victory: The War Diary of General Courtney H. Hodges & the First U.S. Army, by William C. Sylvan and Francis G. Smith, Jr., edited by John T. Greenwood (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2008, 575 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $50.00).

Normandy to Victory: The War Diary of General Courtney H. Hodges & the First U.S. Army, by William C. Sylvan and Francis G. Smith, Jr., edited by John T. Greenwood (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2008, 575 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $50.00).

During Operation Overlord, Maj. Gen. Courtney Hicks Hodges was Omar Bradley’s deputy commander of the First U.S. Army; when Bradley was promoted to command 12th Army Group, Hodges succeeded him as head of First Army.

For an ordinary man, such a promotion might have been daunting, for First Army was destined to be involved in the bulk of the fighting on the Continent, but Hodges was no ordinary man, as his wartime diaries, written primarily by two of his aides, Major Sylvan and Captain Smith, make abundantly clear.

Although Hodges did not personally write the diary, he controlled its contents so that it reflected his viewpoints and concerns. As such, it is filled with the small details that inevitably crop up during battle and make war a uniquely personal adventure.

For example, this entry for March 14, 1945: “General Huebner [1st Infantry Division CG], anxious to get into the scrap once again, called on [Hodges] at ten o’clock this morning and stayed for lunch. He told [Hodges] a wonderful story of a GI who engaged in a brisk fight outside of Gemund, refuged underneath a Boche tank which had been ‘knocked out.’ During the course of the fighting, firing constantly with his carbine, he accounted for 9 Boche. Suddenly the tank moved on, leaving a bewildered and flabbergasted GI lying in the middle of the road. In General Huebner’s words, ‘he flagged it the hell out of there.’”

Hodges and First Army were in the thick of the fighting in Europe—from the hedgerows of Normandy to the liberation of Paris to the battles along Germany’s Siegfried Line and Hürtgen Forest to the Battle of the Bulge. First Army troops were the first to cross the Rhine at Remagen. Later, units of First Army linked up with Soviet forces at the Elbe. “Been there, done that,” could have been Hodges’s motto. His range of experiences among officers was second to none.

As part of the AUSA’s “American Warriors” series, Normandy to Victory makes for interesting, insightful reading about the many command decisions and facets of responsibility faced by an Army commander. Highly recommended.

Short Bursts

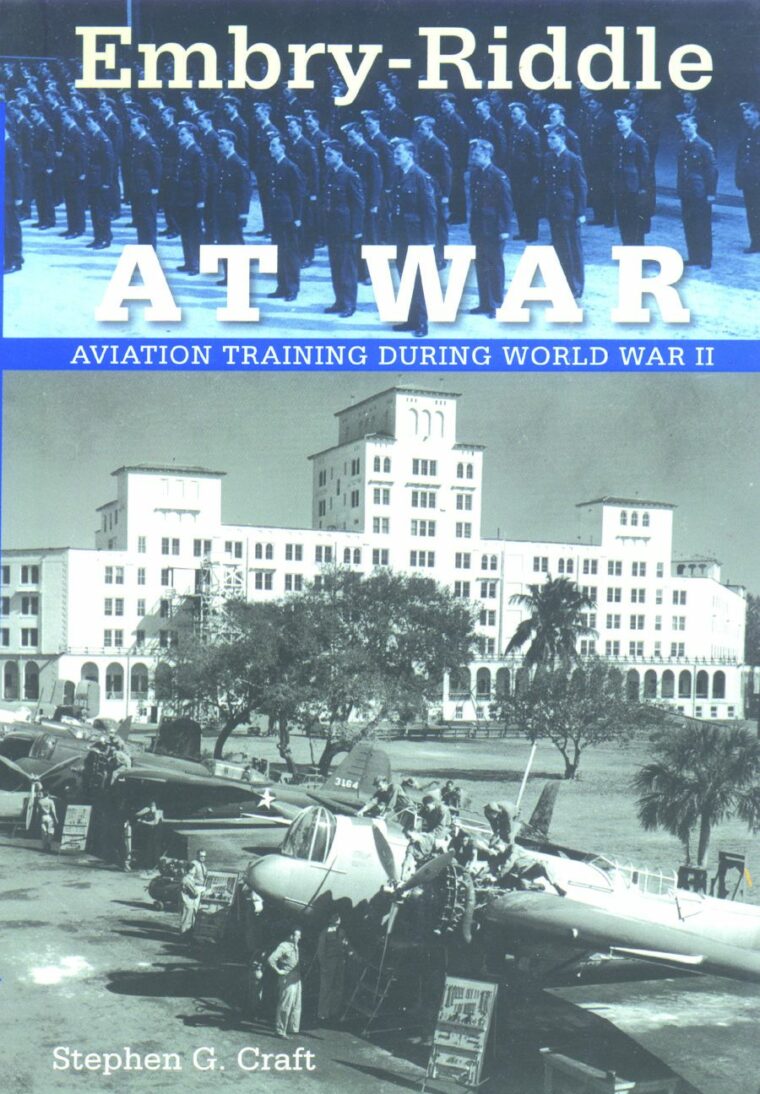

Embry-Riddle at War: Aviation Training During World War II, by Stephen G. Craft (University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2009, 316 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95).

Embry-Riddle at War: Aviation Training During World War II, by Stephen G. Craft (University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2009, 316 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95).

The story of how American aviators were trained for service in World War II has, until now, been largely neglected. With the publication of Embry-Riddle at War, much of that information gap has been spanned.

In October 1939, Embry-Riddle, a private flight instruction school, opened for business in Miami. It quickly became one of the country’s largest facilities for the training of pilots, mechanics, instructors, and aircraft factory workers. By 1944, some 26,000 people had received training at the school.

In his new book, Stephen G. Craft, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, examines the varied components of aviation training, the evolution of a civilian company’s contributions to the war effort, the lives and experiences of those who attended the school, and the role played by Florida during the war.

All in all, a fascinating look at an often overlooked aspect of World War II.

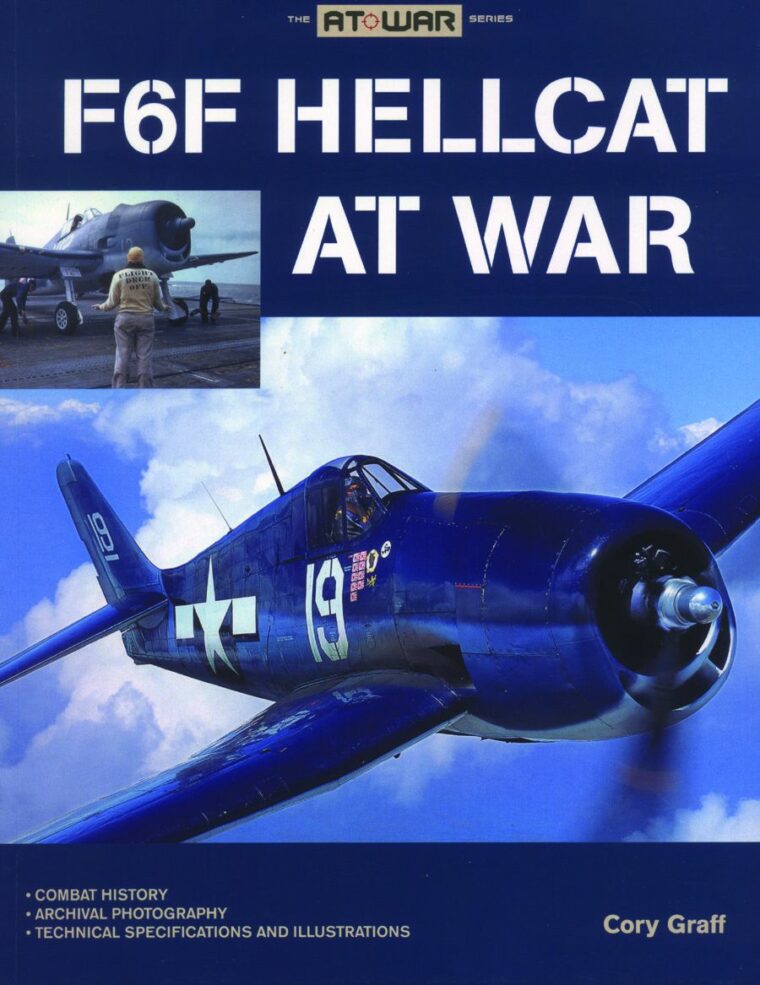

F6F Hellcat at War, by Cory Graff (Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2009, 160 pp., photos, schematics, bibliography, index, softcover, $24.99).

F6F Hellcat at War, by Cory Graff (Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2009, 160 pp., photos, schematics, bibliography, index, softcover, $24.99).

A new addition to Zenith’s oustanding “At War” series, F6F Hellcat at War is bound to get any naval aviation buff’s blood stirring. Over 100 photos, many in color, present the complete history of this legendary, carrier-launched warbird from its initial design and development in the mid-1940s by Grumman Aircraft Corporation at its Long Island factory to its successful combat career in the Pacific.

While the F6F was not the fastest or most maneuverable fighter, pilots loved their Hellcats because they were incredibly tough, marvelously powerful, and easy to fly. During the last two years of the war, Hellcats dominated the skies over the Pacific, turning enemy aircraft into flaming meteors and tallying an astounding kill ratio of more than 19 to 1.

Through compelling accounts, previously unpublished photos, and detailed engineering drawings, Graff does an excellent job of tracing the Hellcat’s lineage and its manufacture, then its role as one of the most feared fighters of the war.

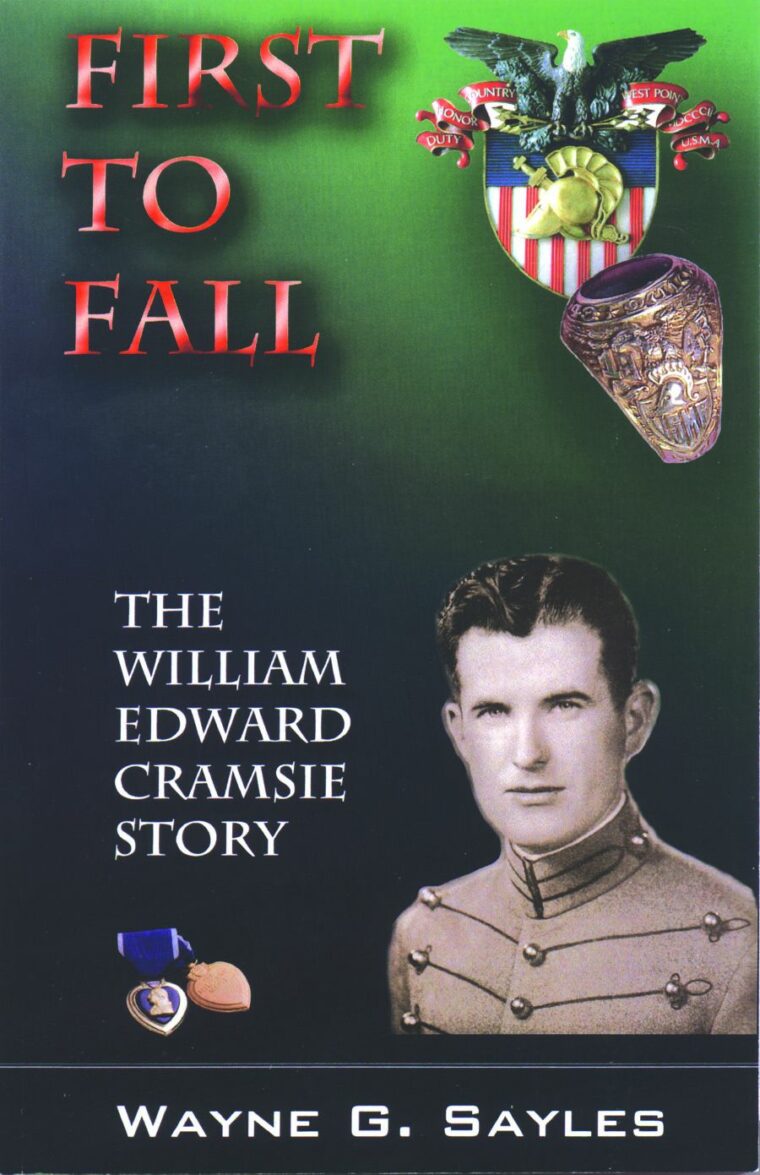

First to Fall: The William Edward Cramsie Story, by Wayne G. Sayles (Clio’s Cabinet Press, Gainesville, MO, 2009, 221 pp., photographs, softcover, $16.95).

First to Fall: The William Edward Cramsie Story, by Wayne G. Sayles (Clio’s Cabinet Press, Gainesville, MO, 2009, 221 pp., photographs, softcover, $16.95).

This fine little book was born when the author came into possession of the West Point class ring of a U.S. Army aviator, the first member of the Class of 1943 to be killed in action. Cramsie, the pilot of a Douglas A-20 Havoc light bomber, was downed in the English Channel in April 1944, his body never recovered.

Yet, somehow, his class ring survived and after more than half a century the author came to own it, a mysterious act that prompted him to dig deeply into the past, discover who Lieutenant Cramsie was, and to write a book about the strangely metaphysical aspects that led to a spiritual bonding of the present with the past.

P.O.W.—A Kriegie’s Story, by Frank Farr (Authorhouse, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 176 pp., photos, softcover, $14.95).

P.O.W.—A Kriegie’s Story, by Frank Farr (Authorhouse, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 176 pp., photos, softcover, $14.95).

Tens of thousands of soldiers, sailors, and airmen were taken prisoner during World War II, but there seem to be relatively few books by or about them.

That is one reason why it is refreshing to come across this self-published memoir by a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress navigator of the 91st Bomb Group. Lieutenant Farr was wounded on his second mission over Germany and shot down on his 17th, during the great aerial battle over Merseburg on November 2, 1944, often called the greatest aerial battle of the war. The 91st lost 13 out of 37 B-17s on that mission. Farr then spent six months in captivity as a kriegie, or a prisoner of war, most of that time at Stalag VII-A.

A fine, well-written memoir that accurately and poignantly describes life behind the wire.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments