By Al Hemingway

Hard-charging and charismatic, U.S. Army General David Petraeus, together with a cadre of subordinates, attempted to rewrite the methods used by the military to wage future wars. As a 1974 graduate of the Military Academy at West Point, he and his classmates were taught the conventional way to fight a war—huge land battles using tanks and artillery. America’s failure in Vietnam, viewed as a counterinsurgency (COIN) conflict, was still fresh in everyone’s mind. The top Army brass were returning to their roots and low-intensity conflicts were forgotten. Petraeus, however, had different ideas.

In his book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2013, 352 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover), Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe correspondent Fred Kaplan has written a timely blockbuster in the wake of the downfall of Petraeus after it was discovered he had an illicit affair with a member of his inner circle, Paula Broadwell, herself a West Point graduate. With his retirement from the Army, Petraeus took over the reins of the Central Intelligence Agency but immediately stepped down when the scandal was unearthed. Broadwell, who had written a book titled All In: The Education of General David Petraeus, may have had access to sensitive top-secret information stored on his computer. That charge was later found to be false.

In his book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2013, 352 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover), Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe correspondent Fred Kaplan has written a timely blockbuster in the wake of the downfall of Petraeus after it was discovered he had an illicit affair with a member of his inner circle, Paula Broadwell, herself a West Point graduate. With his retirement from the Army, Petraeus took over the reins of the Central Intelligence Agency but immediately stepped down when the scandal was unearthed. Broadwell, who had written a book titled All In: The Education of General David Petraeus, may have had access to sensitive top-secret information stored on his computer. That charge was later found to be false.

Kaplan’s story digs deep into what made Petraeus tick. He was an insatiable reader, devouring everything he could that dealt with counterinsurgency wars and the strategies other countries used to win hearts and minds. He firmly believed that, if properly applied, it was the road to winning the war on terrorism. It was, unfortunately, a long, uphill battle for him. Slowly, instructors at West Point began to teach courses dealing with the subject, but they were pejoratively referred to as “Sosh” or the Social Sciences Department.

COIN was created by George Arthur Lincoln, a 1929 graduate who firmly believed that postWorld War II officers had to be “very broad-gauged individuals” if America was to be successful, militarily speaking, in its future conflicts. Students who followed his thinking were called the Lincoln Brigade, another dig because that was the term used for U.S. volunteers with leftist leanings who fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s.

Despite these beginnings, men like Petraeus never backed off and felt that COIN was the way to go, especially in the 21st century. He pushed himself to the limit intellectually as well as physically. When he was accidentally shot in the chest while on a live-fire exercise in 1991, he survived the surgery and was told it would be weeks before he could resume his duties. After several days, he did 50 push-ups for the doctors to demonstrate that he had sufficiently recovered and was subsequently released from the hospital.

As he climbed the promotional ladder, Petraeus made friends who agreed with his assessment of COIN as being the strategy of choice for future conflicts. But Petraeus made enemies as well, other officers who found him overbearing and condescending. In his first tour of Iraq commanding the 101st Airborne Division, his COIN policy enjoyed some measure of success, especially in the city of Mosul, by creating a new political system, screening candidates, and providing services to the city’s inhabitants, all without the approval of his superiors. Later, as commander of all forces in Iraq, he gave the go-ahead to raid Sadr’s Shiite militia, and the Mahdi Army, without letting the Iraqi leaders know his intentions. These were big chances to take, things that could have ended his career. But, they were successful. Sadly, the same results were not achieved in Afghanistan.

Although COIN is a strategy that can be applied for some situations, it is not the solution to every conflict we become involved in. The images of large-scale amphibious assaults, naval gunfire, and massive airpower are what America is accustomed to when fighting a war. The seemingly mundane scenario of nation building does not sit well with many Americans. Spending taxpayers’ dollars only to find that it has failed, as in the case of Vietnam, is just not the American way of war.

Guardian Angel: Life and Death Adventures with Pararescue, the World’s Most Powerful Commando Rescue Force by William F. Sine, USAF (Ret.), Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 239 pgs., photographs, $29.95, hardcover.

Guardian Angel: Life and Death Adventures with Pararescue, the World’s Most Powerful Commando Rescue Force by William F. Sine, USAF (Ret.), Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 239 pgs., photographs, $29.95, hardcover.

At last, a book that gives long overdue and much deserved praise to one of the most respected branches of the military: the U.S. Air Force pararescue jumpers (PJs). For nearly seven decades these highly trained airmen have saved thousands of lives in both war and peacetime situations and, sadly, go largely unnoticed for their gallant efforts. The author, a 27-year veteran of the Air Force, most of that as a PJ, not only delivers a factual account of the teams, including his own personal experiences, but also pays tribute to the sacrifices of his fellow PJs.

Sine wastes no time in grabbing the reader’s attention by starting his book with a 2002 mission in Afghanistan to rescue a seriously wounded member of an Australian Special Air Service team. His description of the mission, the preparation, jumping, and linking up with the Aussies in the desert, is superb. His graphic narrative will hold the reader spellbound as the PJs do everything humanly possible to save a fellow warrior. Unfortunately, on the flight back to Kandahar, the soldier died. Although extremely saddened, Sine is very proud of his team’s performance.

The book follows Sine’s entry into the Air Force and ultimately his decision to become a PJ. His world travels and hair-raising exploits will hold the reader’s attention and give a better insight into a part of the Air Force that is so misunderstood. Unlike their counterparts, Navy SEALs, Army Special Forces, and Marine Recon, the PJs had been overlooked. One hopes Sine’s book will overcome that injustice and bring the PJs from obscurity into the limelight. Sine and his peers have certainly lived up to the PJ motto, “That Others May Live.” An extraordinary book about an extraordinary group of men.

Battle of Stones River: The Forgotten Conflict Between the Confederate Army of Tennessee and the Union Army of the Cumberland by Larry J. Daniel, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 2012, 313 pgs., maps, photographs, notes, index, $38.50, hardcover.

Battle of Stones River: The Forgotten Conflict Between the Confederate Army of Tennessee and the Union Army of the Cumberland by Larry J. Daniel, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 2012, 313 pgs., maps, photographs, notes, index, $38.50, hardcover.

As the author states, the Battle of Stones River, fought near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, has been largely ignored. Although historians declare the battle a draw, Daniel claims it was “strategically a Northern victory” that was sorely needed after the South had won numerous battles in the Eastern theater of operations. Inept leadership had played a major role in the Union defeats and had President Abraham Lincoln frantically searching for a competent general for his Army of the Potomac.

However, the opposing commanders in the Western theater, Confederate General Braxton Bragg of the Army of the Tennessee and Union General William Rosecrans, were far from the best leaders in their respective armies. Rosecrans’s penchant for drinking and quarreling with his superiors was well known. The antisocial and melancholy Bragg was not well liked by his peers, but Confederate President Jefferson Davis placed him at the head of the army nonetheless.

Although Bragg struck first, a dogged defense by the infantrymen of Brig. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s division held the line, preventing it from being breached. In the end Bragg, as he would often do in many battles that he participated in, left the field to set up headquarters in Tullahoma, Tennessee, so his army could regroup. Both sides sustained horrific losses, nearly 13,000 Yankees and more than 11,000 Rebels were killed, wounded, or missing.

The Battle of Stones River initiated the drive to seize the state of Tennessee, and ultimately Atlanta, to win the war in the West. If anything, Stones River and other battles demonstrated that the conflict would be a long, drawn-out affair with both North and South suffering astronomical casualties. However, as New York lawyer George Templeton Strong later observed, “It may have been indecisive, but our troops will stand the wear and tear of indecisive conflict longer than those of slavedom, and soon can be repaired.”

Deliverance from the Little Big Horn: Doctor Henry Porter and Custer’s Seventh Cavalry by Joan Nabseth Stevenson, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2012, 213 pgs., map, photograph, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Deliverance from the Little Big Horn: Doctor Henry Porter and Custer’s Seventh Cavalry by Joan Nabseth Stevenson, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2012, 213 pgs., map, photograph, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

A fresh look at the Little Big Horn massacre—the battle that took the life of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and 210 troopers from the 7th Cavalry—but this time from a medical perspective. Among Custer’s command were three surgeons, two of whom would die that summer day in June 1876. Henry Porter was a contract surgeon, which was a physician who signed a contract that outlined his pay and other benefits for a specific period of time in exchange for care of sick or wounded soldiers.

Ironically, Porter nearly joined Custer’s unit when its doctor, George Lord, was ill. Custer changed his mind when Lord protested and Porter went along with Major Marcus Reno’s horse soldiers. The author vividly describes Reno’s attack on the Indian village and his subsequent retreat across the river to the hilltop where they, and Captain Frederick Benteen’s unit, made their stand. Porter was the lone doctor caring for dozens of wounded and dying men. The intense heat and lack of water added to the misery of those suffering from their wounds until the beleaguered force was rescued by elements of Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry and Colonel John Gibbon’s column the following day.

During Reno’s military court of inquiry in January 1879, Porter testified against him saying he seem embarrassed and confused during the fighting. In the end, Reno was cleared of any wrongdoing but his career was essentially over.

This is a superb book about the hardships and lack of respect contract surgeons were given by the Army in the years after the Civil War. Shunned by the officers of the 7th Cavalry who testified in Reno’s behalf to save the honor of the regiment, Porter nevertheless spoke the truth. According to military surgeon and historian Colonel Percy M. Ashburn, doctors like Porter “have never been accorded their just dues. Many were splendid men.”

African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album by Ronald S. Coddington, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2012, 338 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album by Ronald S. Coddington, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2012, 338 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Photography was still in its infancy during the Civil War. But despite the crude cameras that photographers used and remaining perfectly still while having their picture taken, thousands of soldiers were fascinated by the new technology. Coddington has scoured the country and found dozens of tintypes of African American soldiers who were as proud as their white counterparts when donning their dress uniform to have their photos taken for posterity. The author has identified each individual and has written a brief synopsis of their service during the war and their lives when they were discharged.

The soldiers highlighted in this book fought in every theater of operation. Fifteen-year-old David Moore of Boston was a drummer with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and was present at the Battles of Fort Wagner and Honey Hill in South Carolina and Olustee, Florida, respectively. Private Jesse Hopson served with the 108th Colored Infantry in Illinois and Louisiana. Seaman Alfred Bailey hailed from Virginia and was part of the crew aboard the USS Roanoke.

The work is a moving tribute to the estimated 200,000 African Americans who enlisted in the Union Army—and to those who made the supreme sacrifice.

Pirate Alley: Commanding Task Force 151 Off Somalia by Rear Admiral Terry Knight, USN (Ret.), and Michael Hirsh, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 272 pgs., map, photographs, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Pirate Alley: Commanding Task Force 151 Off Somalia by Rear Admiral Terry Knight, USN (Ret.), and Michael Hirsh, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 272 pgs., map, photographs, index, $29.95, hardcover.

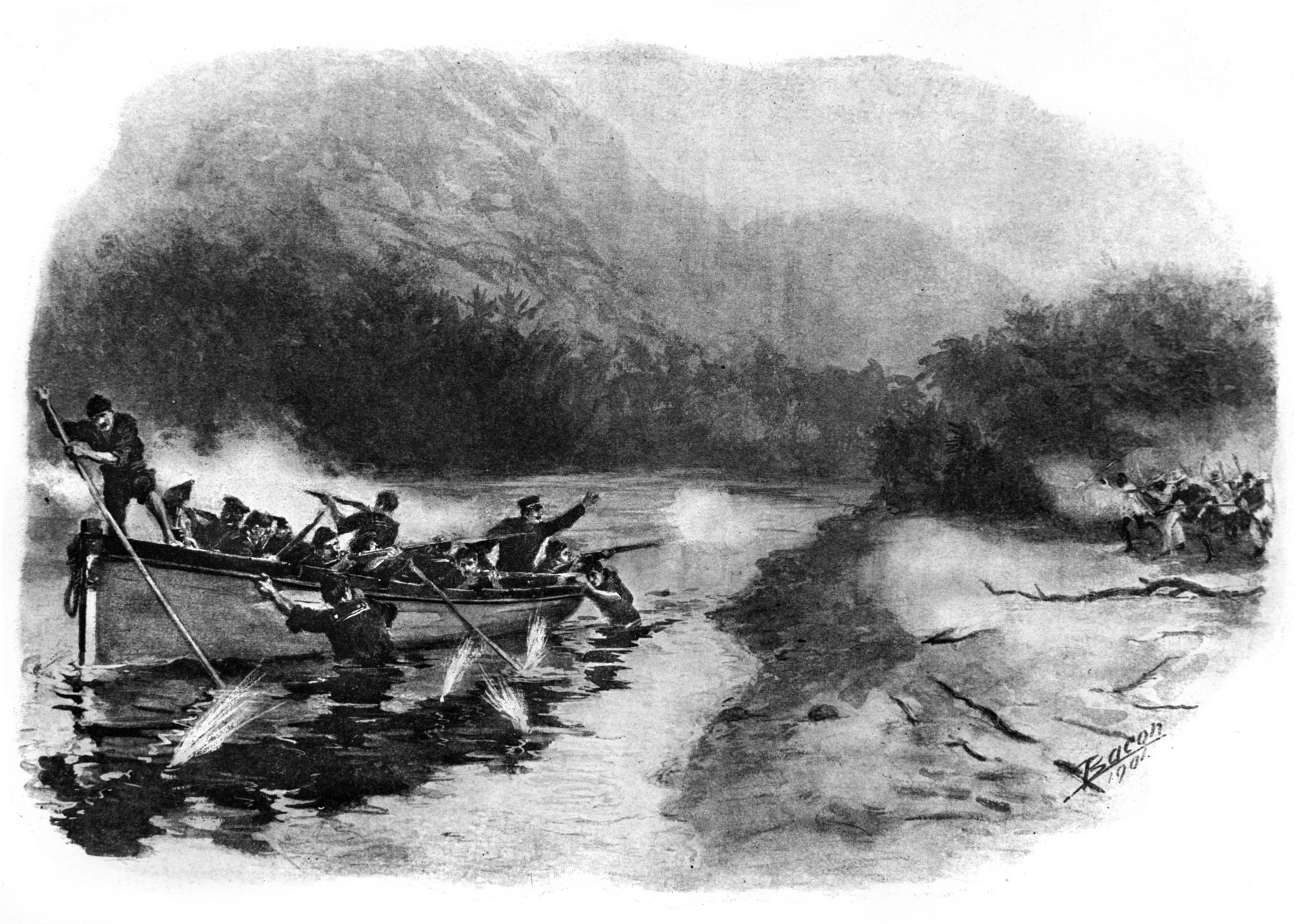

Piracy remains a constant threat today just as it did during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration when U.S. Marine Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon went ashore with eight leathernecks and a few bluejackets to subdue the Barbary Pirates in the early 19th century. Retired Rear Admiral Terry Knight led Task Force 151 as part of a multinational naval group in the Gulf of Aden to keep a watchful eye on the Somali pirates preying on merchant vessels. This waterway is a haven for gun-toting kidnappers who regularly board unsuspecting vessels and take crews and cargo captive in exchange for ransom money. Pirates have a negative impact on today’s global markets, accounting for an astronomical $13 billion annually in lost revenue.

Knight and journalist Michael Hirsh are well aware that these are not the sword-wielding days of swashbucklers where a cannonade from a naval armada would bring most pirates to their knees. But rather it is the 21st century where the rules of engagement are applied. The authors suggest that one method of crippling piracy is to choke off their supply of ransom money.

This intriguing book deals with a subject that should be scrutinized closely by U.S. authorities if piracy is to be curtailed so that ships can travel freely without being molested by seagoing criminals.

Furies: War in Europe, 1450-1700 by Lauro Martines, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013, 336 pgs., illustrations, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Furies: War in Europe, 1450-1700 by Lauro Martines, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013, 336 pgs., illustrations, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Medieval historian Lauro Martines has written a chilling account of the seemingly endless parade of wars that engulfed mainland Europe during the 15th and early 18th centuries. His vivid description of the armies and leaders is a real eye opener for those readers with a keen interest in this period of world history.

But Martines does more than just relate tales of battles, he delves into the logistics, pay, and recruitment of the common soldier, who was more often than not a poor villager himself. The foot soldier was ill fed, underpaid, and severely mistreated by the noble class that commanded the troops.

But it was undoubtedly the civilians who suffered the horrors of warfare more than any other group. The author describes siege warfare, the plundering of helpless villages where looting, murder, rape and torture were commonplace. A terrifying close up of war’s misery during the so-called Renaissance Period when mankind produced tremendous works of art and performed terrible acts of atrocities as well.

The Bazooka by Gordon L. Rottman, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 80 pgs., illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

The Bazooka by Gordon L. Rottman, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 80 pgs., illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

Bazookas are a common weapon in infantry battalions today. But, years ago, they were shunned by the U.S. military as a “devious weapon.” Devious or not, bazookas became an essential piece of armament in World War II to assist the foot soldier in destroying or least damaging enemy tanks. The book goes into the development of the bazooka, its introduction into the military, and how it evolved. From its earliest beginnings to today’s modern army, the weapon is a mainstay against armored vehicles.

Accompanying the text are numerous photographs and the usual detailed illustrations that are in every Osprey book. Another noteworthy addition to the publisher’s weapon series.

Float Planes & Flying Boats: The U.S. Coast Guard and Early Aviation by Captain Robert B. Workman, Jr., USCG (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 324 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $41.95, hardcover.

Float Planes & Flying Boats: The U.S. Coast Guard and Early Aviation by Captain Robert B. Workman, Jr., USCG (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 324 pgs., photographs, notes, index, $41.95, hardcover.

This significant book closely follows the development and expansion of U.S. Coast Guard aviation just before World War II. From its humble beginnings, when flyers took off from the decks of ships in flimsy airplanes, the U.S. Coast Guard has been in the forefront. The author has collected nearly 300 vintage photographs of early aircraft and the pilots who flew them.

Captain Workman gives accolades to the Coast Guard’s first aviator, Cmdr. Elmer F. Stone, a 1913 graduate of the Coast Guard Academy. Stone learned to fly from aircraft pioneer Glenn Curtis and later attended flight school at Pensacola Naval Air Station. He flew his NC-4 aircraft on a historic trans-Atlantic flight in 1919 and later was instrumental in utilizing planes for rescue and patrol. He contributed to the development of catapults and arresting gear on aircraft carriers as well.

For aviation buffs, this book is an important addition to any home library.

For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012 by Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, Free Press, New York, 2012, 736 pgs., maps, photographs, notes, index, $28.00, softcover.

For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012 by Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, Free Press, New York, 2012, 736 pgs., maps, photographs, notes, index, $28.00, softcover.

Since it was first published in 1984, For the Common Defense has been referred to as “the preeminent survey of American military history.” Now, in this new third edition, the authors have extended it to the present day and the terrifying and often complex war on terrorism. The authors relate the interesting fact that victims of terrorist attacks in Europe and the Muslim world outnumber those of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Their number exceeds U.S. military casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan as well.

The authors also provide data on the defense budget cuts proposed by the Obama administration—an estimated $400 billion over the next 10 years. They state that our political leaders should render “security decisions on the basis of expert advice from their civilian and military professionals.”

“Only then,” they say, “will the United States have a common defense.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments