By Blaine Taylor

At 3 am on Sunday, April 29, 1945, a yellow furniture truck stopped at the Piazzale Loreto, a vast, open traffic roundabout where five roads intersected in the northern Italian city of Milan. This industrial center had been held for only four days by Communist partisans, but from 1919 on it had been the spiritual headquarters of the Fascist Party founded there by former journalist and World War I Army mountain corps veteran Benito Mussolini.

In a very real sense, his first political career, ended the day before by his demise, had now come full circle as Mussolini’s dead body was dumped from the van onto the wet cobblestones of the empty roundabout, followed by those of 16 other men and a lone female, his mistress since 1933, Claretta Petacci. All 18 people, their dead bodies thrown out by 10 men, had simply been murdered by Communist Party execution squads in hails of gunfire.

Without any sort of trial, 15 men were shot in the back at the town of Dongo on the shore of Lake Como, with Marcello Petacci slain in the water as he swam in vain for his life.

As for the Fascist Duce (Leader) and his lady, how, where, why, and by whom they were shot are all still unsolved mysteries even today. While the executions of the men were thinly disguised, politically motivated assassinations, the killing of Claretta Petacci was and remains a shameful, common criminal act by ruthless men who had power over her and wrongfully exercised it—no more and no less.

By 8 am, word had gotten around the city via a special newspaper edition as well as bulletins on Radio Free Milan that the hated Duce, revered just four months earlier at public rallies by this very same citizenry, was dead and available for scorn in the Piazzale Loreto. It was there, on August 13, 1944, that the Fascists, egged on by the German SS, had shot 15 partisans. This day’s butchery had been allegedly in revenge for that earlier deed.

A large, ugly, depraved, and nasty crowd of civilians and partisans gathered and quickly got out of control; neither fire hoses nor bullets fired in the air could deter or disperse it.

Two men kicked the late Mussolini in the jaw while another put a pendant in his dead hand as a mock symbol of his lost power; a woman fired five pistol shots into his head as retaliation, she asserted, for the same number of her dead sons, all slain in Il Duce’s series of imperialistic wars since 1935. A fiery rag was thrown in his face, his skull was cracked, and one of his eyes fell out of its socket.

Another woman hitched up her skirt, squatted down, and urinated on his face, which others spit on with abandon, while yet a third brought forth a whip with which to beat his battered corpse. A man tried to stuff a dead mouse into the former Italian premier’s slack, broken mouth, chanting all the while, “Make a speech now!” over and over again.

Pushed beyond hatred and emotional endurance, the angry mob stormed forward and actually trampled the 18 bodies where they lay.

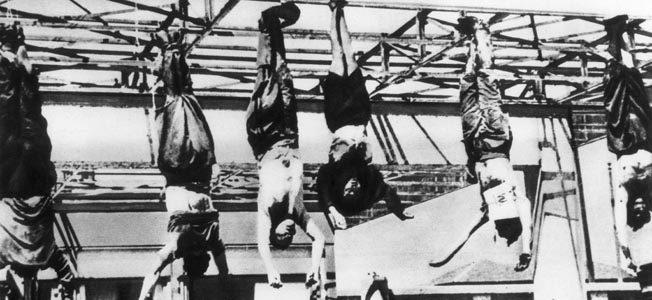

When a burly man picked up the slain Duce by the armpits and held him for the throng to view, the latter chanted, “Higher! Higher! We can’t see! String them up! To the hooks, like pigs!” Thus it came to pass that the bodies of Il Duce, his mistress, and four others were tied with ropes and hoisted six feet off the ground, their dangling bodies lashed by the ankles to the crosspiece of an unfinished Standard Oil gas station that has long since disappeared.

As the sole female corpse was raised, the belle of that gruesome ball’s skirt fell downward around her face, revealing a panty-less torso to the taunts of the crowd. Some accounts say that a woman, others say a male partisan chaplain stepped forward and placed a rope taut around her legs, thus securing her skirt in place for the cameras of the world to film.

A woman gasped aloud, “Imagine, all that and not a run in her stockings!”

Il Duce’s face was blood splashed, and his famous mouth gaped open, while Claretta’s eyes stared dully into space. The former Fascist Party secretary, Achille Starace, dressed in a jogging suit for his daily run, was brought forth, faced the dead, and incredibly gave the stiff-armed Fascist salute to “My Duce!” He was then shot in the back by a four-man firing squad.

Just then, the rope holding the dead body of Francesco Barracu snapped, and his corpse hit the ground below with a sickening thud; Starace was strung up in his place like a piece of meat beside the others. Next, Mussolini’s rope was cut, and he fell to the cobblestones on the top of his head, his brains oozing out onto the wet street.

At 1 pm, the combined protests of the Catholic cardinal of Milan and the just arriving American military government succeeded in having the bodies taken down, placed in plain wooden coffins, and sent to the city morgue.

There, the body of Mussolini was formally autopsied. The 5-foot, 6-inch tall Duce weighed 158 pounds, with sparse white hair on his battered, bald head. Because he was hit by seven to nine bullets while still alive, the immediate cause of death was determined to have been four shots near the heart. His stomach bore ulcer scars, but none of the long-rumored syphilis was visible. He had had a minor gall bladder problem, however.

Mussolini’s corpse was buried anonymously in Milan’s Musocco Cemetery in section 16, grave 384, while part of his brain was handed over for study to St. Elizabeth’s Psychiatric Hospital in Washington, D.C., and only returned to his widow, Donna Rachele, decades later.

Claretta had been killed by two 9mm bullets, which added to the mystery of the weaponry used. She was also buried in Milan under the name of Rita Colfosco and in 1956 was exhumed by the Petacci family, which had meanwhile returned to Italy from its Spanish exile at the end of the war. Today her remains rest in Rome’s Verano Cemetery in a pink marble tomb topped with a white marble statue. Rumor had it that her corpse had been retrieved to secure hidden gems sewn into the hem of her skirt.

The bloody killings and their gruesome aftermath horrified the world, but to the Italians the entire episode conjured up mainly postwar political connotations: to the beaten Fascists, the partisans had acted simply as “the Italian arm of the Red Army,” as the agents of Josef Stalin in Moscow; while to the rest of the body politic, the events at the Piazzale Loreto symbolized the birth pangs of the coming socialist republic that even Mussolini himself would have supported over the monarchy that had both hired and fired him.

The final saga for Mussolini and Petacci began when Il Duce arrived in Milan at 7 pm on April 18, just ll days before his death, with Ms. Petacci, the eldest daughter of a former Vatican physician, following later. On the 21st, an American OSS plan to capture Mussolini by paratroopers was vetoed, while his own German Waffen SS battalion-sized escort was removed and sent to the front to fight the advancing Allies and Communist partisan forces.

Even some of his own Fascists, as well as Claretta’s larcenous brother Marcello, were plotting to have Mussolini murdered while suspicions were running deep among members of his circle that the Germans were planning to trade him to the Allies to save their skins.

The Catholic Church offered Il Duce asylum, as did several South American countries. He refused and vowed he would never surrender but instead would lead a Fascist last stand in the Valtellina region, on the far side of Lake Como.

When the betrayed Duce heard of German plans for a secret surrender of all Axis forces in northern Italy on April 25, he left Milan in a huff for the town of Como, 25 miles distant, trailed by his SS bodyguard chief, Lieutenant Fritz Birzer and Secret Police Lieutenant Otto Kisnatt, each ordered not to let him out of

their sight or to shoot him themselves if he tried to escape.

He did try—twice. He was now a man on the run, but why?

Although informed that neutral Switzerland would not accept him, his family, or any other Fascists, Mussolini nevertheless seemed to be headed there rather than, as he asserted, to a final battle that drew only 12 faithful soldiers.

It has also been suggested that Mussolini meant instead to cross the frontier into the Nazi-held South Tyrolean region of Austria and there stand until death with still-resisting German troops, but even now no one really knows for sure.

Yet another theory has lingered since 1945— that Il Duce was trying to rendezvous with British secret agents to trade his life and those of the members of his sizable entourage in return for secret prewar letters between him and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, as well as for others penned during the final stages of the war.

There was also the hoard of loot that the fleeing Fascists took with them in a convoy of 28 vehicles, an estimated millions in cash, checks, jewels, gold bullion and other riches taken from slain Jews, all later stolen by the partisans and used to launch the postwar Italian Communist Party as the largest in Western Europe. This has been referred to ever since as Il Duce’s Gold or the Dongo Treasure in reference to where it was captured on April 27 along with Mussolini and his fleeing minions.

All of this has been endlessly discussed since 1945 in a veritable phalanx of articles and books in both English and Italian, the most recent being an excellent trio of works brought forth for the 60th anniversary of the end of the Italian campaign and the Duce-Petacci-Fascist slayings of April 28, 1945.

The first two books, written by Ray Moseley and Luciano Garibaldi, respectively, appeared in 2004 and were titled Mussolini: The Last 600 Days of Il Duce and Mussolini: The Secrets of His Death/Did Winston Churchill Order Mussolini’s Execution? The third volume of this trio, Sergio Luzzatto’s lyrical The Body of Il Duce: Mussolini’s Corpse and the Fortunes of Italy appeared in 2005.

On Friday, April 27, the convoy of German SS, Luftwaffe, and Italian Fascist vehicles of uncertain numbers was stopped by a small, vastly outnumbered unit of the 52nd Garibaldi Partisan Brigade commanded by Count Pier Luigi Bellini delle Stelle, alias Pedro, at the small village of Musso along Lake Como. Bluffing as to the size of their actual force, the Red negotiators told the Germans that they could proceed unharmed, but only on the condition that no Italians were in the enemy column.

Luftwaffe Lieutenant Hans Fallmeyer, according to Moseley, and Lieutenant Fritz Birzer agreed to these conditions. The latter hastened to the hidden Duce, who was inside an armored car and armed with a submachine gun and wearing his standard gray-green forage cap and uniform of the Fascist Militia.

Mussolini argued that all of his entourage should be allowed to continue, but the Nazi lieutenant was firm, insisting that only the Duce himself could go and that even Claretta had to be left behind. Urged by her to accept the terms, an embarrassed Duce reluctantly agreed.

Birzer got his own overcoat and steel helmet from a Luftwaffe sergeant and gave them to Mussolini to wear, but the mortified Duce protested that he would be ashamed to be found dressed as a German and hidden in a German vehicle. However, he finally relented.

The disguised Duce slipped out of the armored car and into a truck of Luftwaffe men, wearing the German steel helmet backward until Lieutenant Birzer righted it. Tearing off his own Fascist Militia jacket, the crestfallen Mussolini replaced it with the field gray overcoat that was discovered in Rome in 1999, to further hide the rest of his own uniform, complete with the traditional black shirt of the Fascisti. Sitting quietly at the far end in the left corner of the fourth truck in line, Mussolini pretended to be drunk.

The hidden Duce was betrayed by an Austrian who told the partisans, “There are Italians; have the trucks searched,” as well as an Italian Fascist, Nicola Bombacci, who lamented, “He is with us! It is not fair that he should get away!” Thus forewarned, the Communists stopped the convoy a second time, at the next village, Dongo, just opposite the town hall.

A former sailor in the Italian Navy, a clog-maker from Dongo named Giuseppe Negri who had joined the Partisans, searched the truck and was startled to see the profile of the man he had formerly served. He reported immediately to Urbano Lazzaro (alias Bill), asserting, “Oh, Bill! We’ve got the Big Bastard! … It’s really Mussolini! … I’ve seen him with my own eyes!”

Incredulous, Lazzaro climbed into the truck himself and approached the mysterious figure pointed out to him obligingly by the real Luftwaffe men who knew the truth. Lazzaro tapped the seated man on the shoulder and called out, “Comrade!” but got no answer. He then stated louder, “Your Excellency!” and tapped his shoulder once more, but was still met with silence and no movement. He addressed the silent figure yet a third time: “Cavalier Benito Mussolini!”

Later he recalled, “I take off his helmet and see his bald pate and the characteristic shape of his head. I take off his sunglasses and lower the collar of his coat. It is he, Mussolini.”

Lazzaro removed the man’s machine gun and was offered in turn from his unbuttoned coat a 9mm, long-barreled Glisenti automatic pistol without a word in response to the question, “Do you have any other weapons?”

He stood up and said, “I am Mussolini. I shall not make any trouble.”

Arrested by Lazzaro, the now meek Duce told the Germans not to defend him; he was taken from the truck and marched to the town hall, his captors following respectfully behind. There, according to Moseley, “He took off his coat, which was too long for him, and was found to be wearing a black shirt and a pair of Militia trousers. He wore boots, but had no jacket.”

At Milan, the slain Duce still had on the trousers and the boots, but the shirt had disappeared while he swung from the girders of the filling station and was also absent from the coffin in the morgue, as photographs clearly show.

Also taken by Lazzaro from the captured Duce was a briefcase and other baggage that had the originals of his most important, personal papers, to which Mussolini exclaimed, “Take care of those bags! They contain Italy’s destiny!” These files included his letters to and from Churchill, correspondence with Hitler, and a document covering the January 1944 Verona Trial of the traitors who had voted against him in 1943. A fourth set of papers detailed the alleged homosexual activities of Italian Crown Prince Umberto, then the designated lieutenant general of the realm.

Lazzaro gave all of this to his superior, Luigi Canali (alias Captain Neri), who wanted to honor the terms of the 1943 armistice with the Allies that required the Duce to be turned over to them for trial. The top Communists in Milan ignored this legal clause. Neri also opposed the seizure of the Dongo Treasure by his Communist bosses, and some have accused him of having shot Mussolini himself.

According to some sources, Neri was assassinated by the Communists in May 1945, not because of having done that, but for bringing the British secret service into the affair.

Ironically, Neri had been drafted into the Italian Army in 1936 as a lieutenant of engineers in East Africa, later took part in the retreat of the Expeditionary Corps in Russia, became a Communist, and helped found the 52nd Garibaldi Partisan Brigade that captured his former Duce.

A further twist to this complicated tale was that of Neri’s own mistress: Giuseppina Tuissi (aka Gianna), who was shot by their Communist colleagues on June 23, 1945. Her body was dumped into Lake Como.

The first and last of Mussolini’s files of personal papers disappeared forever, but the others were copied by the Allies and then deposited in the Italian State Archives after being examined by the Communists. As a precaution, however, Mussolini had made a three copies: one for Claretta, which she gave to Marcello and which the partisans seized; and a second for the Imperial Japanese ambassador to the Salo Republic, Baron Shinrokuro Hikada, which was delivered by him to the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo. Mussolini gave the third and final set to his Fascist Education Minister, Carlo Alberto Biggini, who died supposedly of cancer in the hospital in the autumn of 1945, one of the few top Fascists not to have been shot.

There were, too, the now infamous Duce Diaries, 10 notebooks in his own handwriting that were given to Baron Hikada as well. Most of these vanished. Of the Duce’s own original papers and documents personally seen by Lazzaro, 344 pages dwindled to little more than 70 after several deletions by interested parties.

Some historians speculate that on September 15, 1945, at a secret meeting held between British agents and Como Communist leader Dante Gorreri, the latter turned over 62 Duce-Churchill letters for an estimated 2.5 million Italian lira laundered in Switzerland and then returned to Italy to be used to launch the new republic. Supposedly, during this exchange, the partisans agreed to accept the blame for the killing of Claretta, who had allegedly been shot by the British because she knew of the secret correspondence.

According to Bruno Giovanni Lonati (alias Ciacomo), a British Special Operations Executive agent, “Captain John,” the alias of Robert Maccarrone, shot both the Duce and Claretta. The name of a second British agent, Malcolm Smith, aka Johnson, also surfaced. All this was part of a fantastic yarn known as the so-called British Thread.

Taken away, Mussolini was rejoined at the De Maria farmhouse at Bonzanigo by Petacci, who begged her captors to shoot her as well if that was to be the ultimate fate of the apprehended Mussolini. They spent the night together in a peasant bed.

Meanwhile, a Communist murderer codenamed Colonel Valerio was sent from Milan to execute them both. Valerio has been identified over the decades as several different Communists.

As he went into the De Maria farmhouse to meet the captive Duce for the first and only time, Valerio chortled, “I’ll tell him I’ve come to rescue him!” The men hustled the Duce, now sporting a black beret, and Claretta, frantically searching among the bedsheets for her missing panties, out the door and into a waiting car.

Later, 19-year-old Dorina Mazzola claimed to have seen both victims gunned down just outside the De Maria farmhouse, and it was then that the long-accepted version of their having been shot by the gate of the Villa Belmonte was first challenged by historians.

Exactly who actually shot first Claretta and then Mussolini has been debated. It was even asserted that a second shooting of the already dead bodies was held at the Villa Belmonte. Some others said that the doomed pair committed suicide inside the De Maria farmhouse instead.

At a Communist rally in Rome in March 1947, a former partisan named Audisio was officially proclaimed before an audience of 40,000 as the killer of Mussolini and Petacci. This occurred during a campaign for the Italian Parliament, and he was elected.

It was also subsequently agreed that both Audisio’s submachine gun and pistol failed to fire in succession and that it was a 7.65mm L/MAS 1938 model F20830 submachine gun with a red ribbon tied to the end of the barrel and belonging to another partisan named Moretti that was the actual murder weapon. Captured from the Fascists, the weapon reportedly fired five French-made bullets into Mussolini while the mysterious 9mm rounds fired into Petacci came from an unknown weapon.

No mention has been made of where the weapons are today. In all, Audisio is said to have given as many as 22 different published accounts of these events before his death in 1971.

Valerio claimed that Il Duce was a trembling coward in death, begging that his life be spared: “I will give you an empire!” But other accounts stated that he pulled himself together after being told “Your luck has run out,” and having seen how Claretta argued with the murderers, “You cannot kill us like this!” before being gunned down herself.

One partisan claimed that Mussolini’s last words were, “Shoot me in the chest!” while another felt that “Aim for my heart!” was, in fact, more accurate. Still other versions are ”Long live Italy!” and “But, colonel….”

Afterward, Audisio was supposed to have said, “Look at his face! It suits him, doesn’t it?” In any event, the man contemptuously called “Hitler’s gauleiter for northern Italy” by his enemies and code-named “Karl Heinz” by the Germans was dead.

Formal Fascism died on the Piazzale Loreto on April 29, 1945. In perhaps the greatest irony of all, Audisio and his men very nearly never made their rendezvous with destiny in Milan. After having bluffed their way past U.S. Army patrols, which never searched the yellow truck, they were arrested by yet another partisan unit while on their way into the city at 10 pm on the 28th.

“They’re Fascists!” screamed the irate officer in command, and this seemed to be confirmed when he found the list of the top Fascists that Colonl Valerio himself had written to identify those to be shot.

The names of the slain “Dongo 16” have rarely been noted. They included Fascist Party Secretary Alessandro Pavolini; Francesco Maria Barracu, Paolo Zerbino, Fernando Mezzasoma, Ruggero Romano, and Augusto Liverani, Salo Republic ministers all; Inspector for Lombardy Paolo Porta; the Duce’s secretary Luigi Gatti; Bologna University Rector Goffredo Coppola; Stefani News Agency Director Ernesto Daquanno; Agricultural Federation employee Mario Nudi; Duce aide Vito Casalinuovo; Italian Air Force pilot Pietro Calistri; public relations man Idreno Utimpergher; Mussolini’s longtime socialist friend, Nicola Bombacci; and Claretta’s brother, Marcello, whom the partisans initially mistook for a Spanish diplomat and then for Il Duce’s son, Vittorio.

Neo-Fascism lives on mainly in the person of the Duce’s granddaughter, Italian film actress Alessandra Mussolini, child of Mussolini’s jazz musician son Romano and Sophia Loren’s divorced sister. Alessandra was elected to the nation’s legislature in the 1990s.

When neo-Fascist Domenico Leccisi of the MSI Party stole the Duce’s body on April 23,1946, he unwittingly launched the late Duce’s second political career as a traveling corpse. Leccisi had seen Mussolini twice, in 1936 and 1945, and found his remains to be still recognizable. Later, Leccisi was also elected to Parliament and even concocted a plot to kill Audisio. Fascist deputies were returned to office in the 1953 elections.

As for the missing Duce, his body was surrendered to a pair of Franciscan friars and hidden in the convent of Cerro Maggiore with the knowledge of the cardinal of Milan and of the Italian Socialist government for 11 years. By that time, the remains were skeletal and fit into a small trunk.

The so-called Padua Trial began on April 29, 1957, to resolve the issue of the disappearance of the Dongo Treasure and the subsequent murders of those linked to it. The trial adjourned inconclusively the following August and was never reconvened.

On September 1, 1957, Mussolini’s remains were finally returned to his widow and entombed in the family crypt at Predappio, the town where Il Duce was born in 1883. It has since become a shrine for 70,000 pilgrims and tourists who visit annually. It is guarded around the clock by twin neo-Fascist sentries in long capes.

The crossbar of the Milan gas station became a sort of monument to socialist and communist unions that staged parades past it, and painted upon it were the names of the five slain Fascisti and Claretta Petacci who had been suspended from it. Later, a merchant supposedly bought the piece as an investment for resale. Ironically, the flames of the memory of that day in Milan were fanned not by the Socialists who wanted to forget it, but rather by the neo-Fascists as a symbol of rightist anger.

It appears that the long-forgotten Claretta Petacci may yet have a final word. In 1945, when she took her leave of Lake Garda to chase after her departed Duce, she left behind with the caretakers at the Villa Mirabella her own papers.

These were two large boxes of 600 love letters from the Duce spanning the 12 years of their passionate association from February 1933 to April 1945. Containing not only gossip but also highly valuable military, political, and diplomatic tidbits, they were buried for safekeeping at Gardone and willed by Claretta to her younger sister and confidante, Myriam Petacci.

Dug up by the family in 1950, the 15 volumes were immediately confiscated by the Italian Socialist Republic. Myriam lost her case for repossession in the courts and died in 1991. The documents were ordered sealed for 50 years, or until April 25, 1995. When that date came and went, they remained sealed as they are today.

Today, the sole family heir is the younger son of Claretta’s murdered brother Marcello, broke and living in a trailer park in Phoenix, Arizona. Someday, when his legal inheritance is duly honored, Signor Petacci will become one of the most famous and richest men in the world as his late aunt’s papers are released and published globally.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments