By Al Hemingway

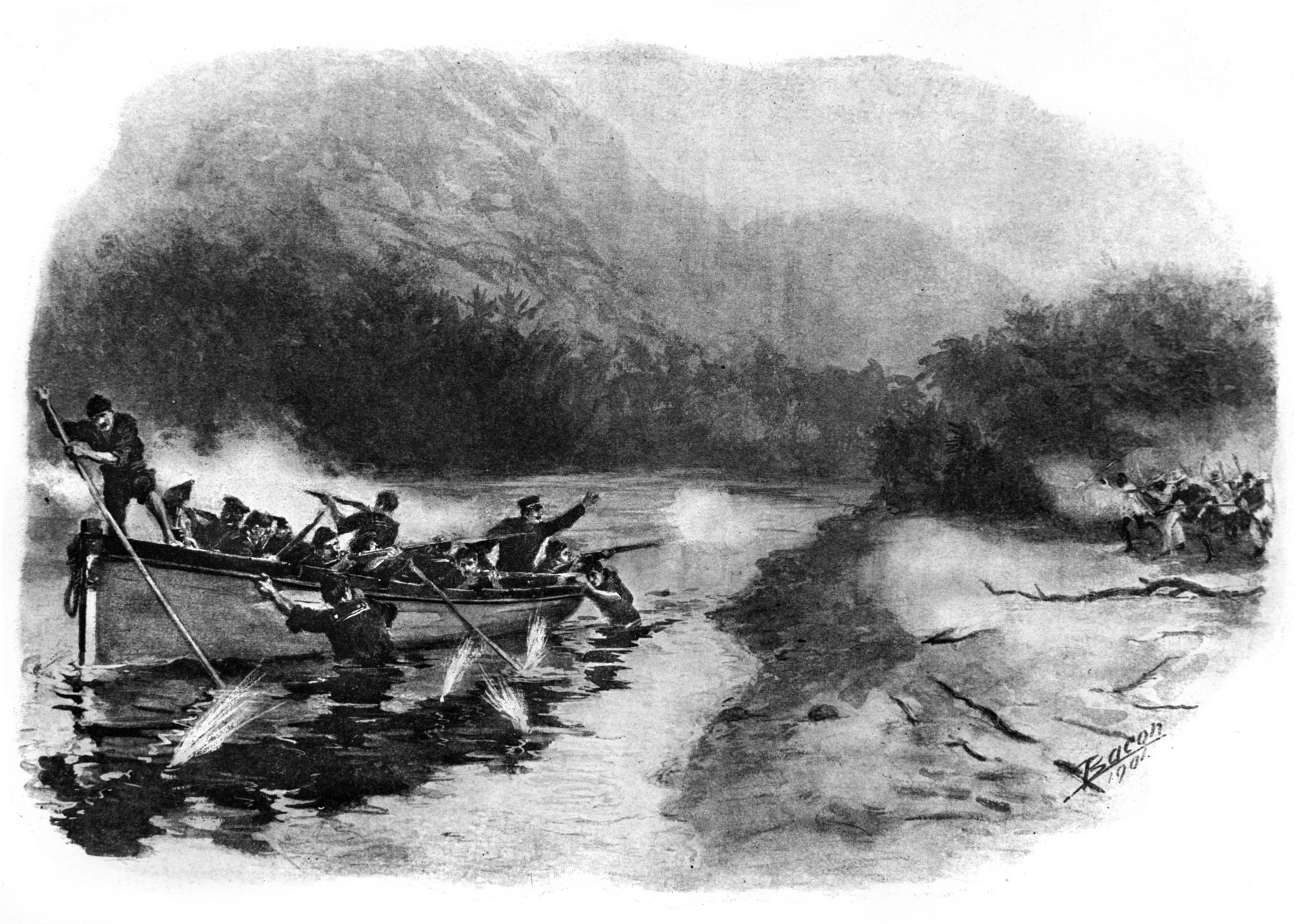

On the morning of April 12, 1899, a U.S. Navy cutter from the USS Yorktown with a crew of 14 sailors and one officer cautiously made its way up the Baler River in the province of Aurora in the northeastern section of Luzon Island in the Philippines. In command was the Yorktown’s navigator, Lieutenant James C. Gillmore, Jr., a 45-year-old naval officer who had volunteered for the dangerous assignment to bolster his lackluster career. Several hours earlier, Ensign William H. Stanley and Quartermaster 3rd Class John Lysaght, who had accompanied Gillmore to shore, were let off to reconnoiter the surroundings, especially the local church where a garrison of Spanish soldiers was holding off rebel forces led by Captain Teodorico Novicio.

What happened next is still shrouded in mystery. Gillmore deliberately disobeyed orders and maneuvered the vessel upriver until it was greeted by a volley of rifle fire from the thick underbrush along the bank of the waterway. Within minutes, the crew was in trouble. Two men were killed outright and five others wounded, two of them seriously. Insurgents seized the surviving Americans, who ultimately would have to endure a horrific eight-month-long journey that would take them hundreds of miles from civilization, in what Gillmore would later refer to as “the devil’s causeway,” before being rescued by two U.S. Army battalions.

What happened next is still shrouded in mystery. Gillmore deliberately disobeyed orders and maneuvered the vessel upriver until it was greeted by a volley of rifle fire from the thick underbrush along the bank of the waterway. Within minutes, the crew was in trouble. Two men were killed outright and five others wounded, two of them seriously. Insurgents seized the surviving Americans, who ultimately would have to endure a horrific eight-month-long journey that would take them hundreds of miles from civilization, in what Gillmore would later refer to as “the devil’s causeway,” before being rescued by two U.S. Army battalions.

In his new book, The Devil’s Causeway: The True Story of America’s First Prisoners of War in the Philippines and the Heroic Expedition Sent to Their Rescue (Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2012, 432 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover), Matthew Westfall has written a marvelous account of the crew members of the ill-fated Gillmore party and the hardships their rescuers also had to suffer as they trekked deep into the jungles of Luzon to free them.

The reasons behind Gillmore’s illogical strategy of navigating up the Baler River and putting himself and his crew in jeopardy remain unclear. As Westfall points out, Gillmore had been passed over for promotion because of his repeated bouts with alcoholism and conduct unbecoming an officer. He may have hoped that his assignment to the Philippines could transform his career. He was correct—but at the expense of his crew and others.

Westfall gives an excellent overview of the global picture at the time of the incident and why the United States was fighting in the Philippines in the first place. With the exception of 17-year-old Apprentice 2nd Class Denzell George Arthur Venville, who was left behind at Baler because his wounds would not heal, the remainder of the group was taken across miles of treacherous jungle as pawns to be used against American interests. Elements of the 33rd and 34th Regiments of the U.S. Volunteer Infantry gave chase to free their fellow comrades and snare the leader of the insurrection, General Emilio Aguinaldo, the “center of gravity” in the ongoing fight for Filipino independence from Spain and the United States.

In doing his research, Westfall uncovered numerous little-known facts surrounding the attack, the rescue of the Yorktown’s sailors, the hunt for Novicio, and perhaps saddest part of all, the whereabouts of youthful seaman Venville, who was murdered by natives. Venville’s body was transported back to his hometown of Portland, Oregon, and buried with full military honors.

Ironically, Gillmore went on to have a successful career despite his inexcusable blunder that spring morning in Baler. No one dared criticize the man who was then being praised in the media for his heroism. He retired in 1911 with the rank of commodore. On June 13, 1927, Gillmore succumbed to the aftereffects of a massive stroke he had suffered three years earlier. Newspapers still praised his exploits in the Philippines and his gallantry during the Spanish-American War.

“The story of Gillmore is more than a tragic tale of one man,” Westfall writes. “It is a study of impetuous decisions and misused privilege, of arrogant attitudes and failed leadership, all on a desperately human scale, and which came to embody one nation’s anxious grasp at empire at the end of the nineteenth century. Through that lens, it was at the terminus of Baler, during Gillmore’s failed rush up the river, where that grasp at expansion stuttered and then stalled.”

Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence by Alan Gilbert, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2012, 369 pp., notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence by Alan Gilbert, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2012, 369 pp., notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Many African Americans during the American Revolution were recruited and promised their freedom by British forces following the release of the Dunmore Proclamation in November 1775. That proclamation, by the Earl of Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia at the time, stated that any slaves who left their masters and fought for the British would be granted their freedom. Slave owners throughout the South were incensed at the offer and feared a widespread slave revolt. But though an ambitious move, the proclamation ultimately failed and Dunmore (a slaveholder himself) fled Virginia the following year.

In the end, an estimated 20,000 African Americans fought on the British side during the Revolution. Following the surrender at Yorktown to General George Washington’s Continental forces, many of the black soldiers made their way to Nova Scotia, Great Britain, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and other Caribbean islands. The compilation of their names, called the Book of Negroes, contained more than 3,000 entries.

Author Alan Gilbert, a professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, gives readers a fascinating account of the trials and tribulations of African American slaves who embraced the British cause hoping that it would give them the victory they so desperately yearned for—freedom from bondage. It would take another army, this one American, to complete that task in the Civil War.

Terrible Swift Sword: The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan by Joseph Wheelan, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2012, 387 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Terrible Swift Sword: The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan by Joseph Wheelan, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2012, 387 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover.

There is little doubt, as author Joseph Wheelan makes clear, that Philip H. Sheridan was among the top three Union generals, Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman being the other two. Together, the three contributed greatly to the Union victory in the Civil War. Their “total war” policy was eagerly embraced by President Abraham Lincoln, and Sheridan’s troopers ruthlessly carried it out, in the biter Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1864-1865, burning crops and supplies and executing suspected Confederate guerrillas.

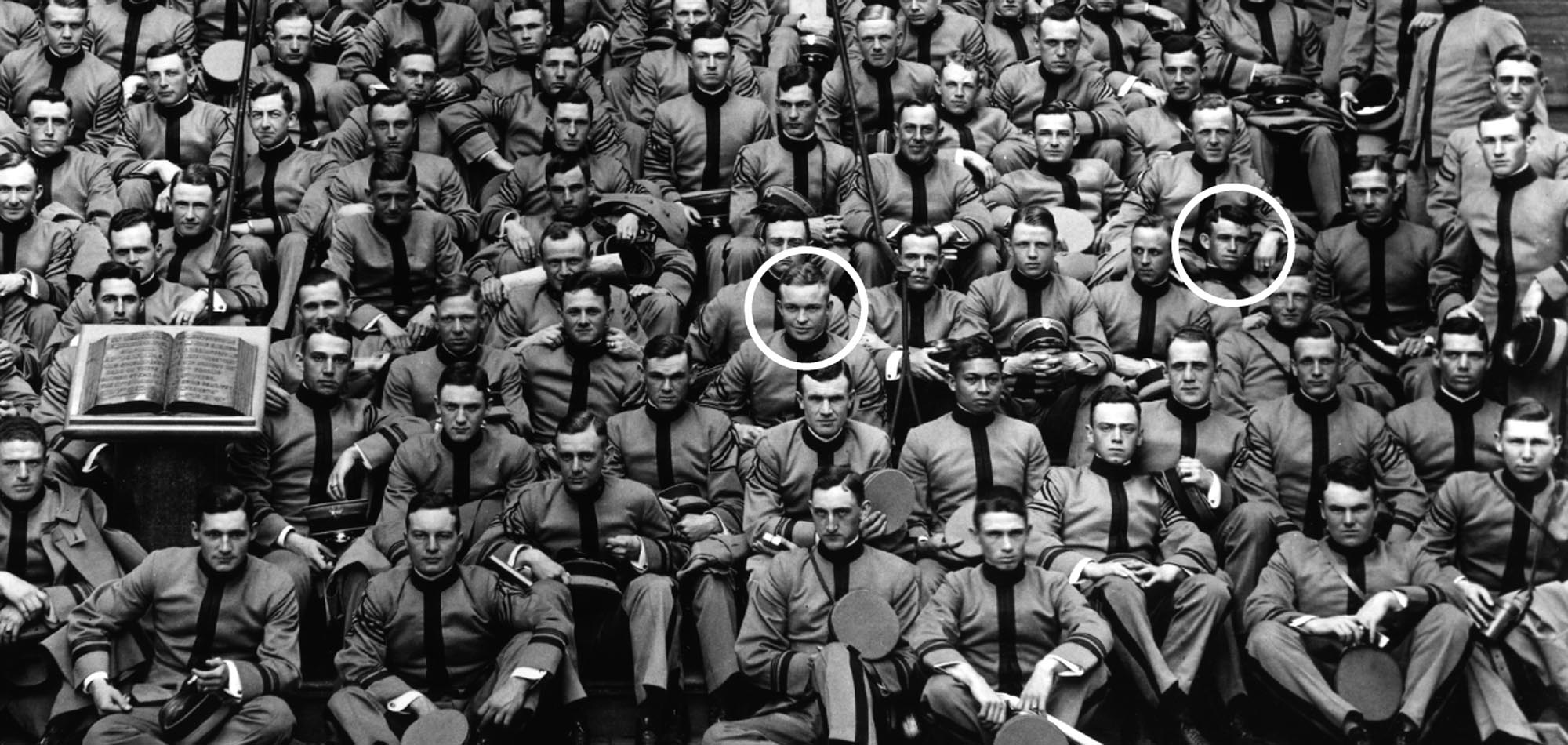

The diminutive Sheridan came from an obscure background. No one is exactly sure where he was actually born, perhaps at sea during his immigrant parents’ journey from Ireland to America. Although graduating in the bottom third of his class at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Sheridan nevertheless rose through the ranks during the Civil War by “leading from the front.” His audacity and leadership on the battlefield were demonstrated most clearly at the Battle of Cedar Creek in October 1864, when he turned his army’s rout after a surprise Confederate attack into an overwhelming victory later that same day.

Sheridan went on to become General of the Army when Sherman retired and oversaw the ongoing campaigns against the Plains Indians and Apache warrior Geronimo. Surprisingly, Sheridan was also a staunch supporter of the national parks system and took a leading role in preserving such natural treasures as Yellowstone National Park.

Sheridan made enemies along the way, especially his old Civil War subordinate, General George Crook, whom Sheridan replaced with General Nelson Miles during the Army’s lengthy efforts to capture Geronimo. After his death in 1887, Sheridan’s mystique continued, and a statue was dedicated to him in Washington, D.C., in 1908. He is depicted, atop his favorite horse, Rienzi, leading his troops at Cedar Creek—his shining moment captured for all eternity in bronze in the nation’s capital.

Gentlemen Bastards: On the Ground in Afghanistan with America’s Elite Special Forces by Kevin Maurer, Berkley Caliber Books, New York, 2012, 243 pp., photographs, $26.95, hardcover.

Gentlemen Bastards: On the Ground in Afghanistan with America’s Elite Special Forces by Kevin Maurer, Berkley Caliber Books, New York, 2012, 243 pp., photographs, $26.95, hardcover.

Since their inception, the U.S. Army Special Forces, commonly referred to as Green Berets, have been in the middle of America’s various wars, from Vietnam to Iraq to Afghanistan. Their behind-the-lines clandestine activities have produced valuable intelligence for conventional troops in the field. Award-winning journalist Kevin Maurer has written an intriguing book dealing with today’s special forces and how they are coping with the insurgency conflict in Afghanistan, especially their experience with the Afghan National Civil Order Police, or ANCOP.

Maurer has done an exceptional job of writing about the day-to-day duties of the special forces soldiers. For 10 weeks he was imbedded with a team assigned to ANCOP. The author suggests that the special forces are “slowly losing [their] unconventional mindset” by not being in civilian clothes and interacting with the local populace to gain their trust, as they did in Vietnam. Nevertheless, he argues that the Afghans in ANCOP “will be better in the future” because of the presence of SF teams. He has succeeded in capturing the obstacles the soldiers face daily from an inaccessible Afghan culture and a bureaucratic system that “takes the fight out of units.”

Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History by John Fabian Witt, Free Press, New York, 2012, 512 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $32.00, hardcover.

Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History by John Fabian Witt, Free Press, New York, 2012, 512 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $32.00, hardcover.

War, it is said, brings out the best and the worst in people. Armed conflict can transform ordinary individuals into cold and callous beings bent on killing the enemy or unarmed civilians with little or no remorse. But when has one gone too far? Indiscriminate killing of civilians, executing prisoners of war, torture, and inhumane treatment of prisoners would certainly seem to cross the line

Yale law professor John Fabian Witt has written a provocative book about that subject. Long before the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War and the water- boarding of suspected terrorists after the September 11 attacks, the United States was struggling to come to grips with the question of appropriate conduct for soldiers in the field and the treatment of prisoners.

It was not until the Civil War that President Abraham Lincoln issued a set of 157 rules intended to guide Union soldiers in their behavior during wartime. In the end, Lincoln’s comparatively enlightened laws of war were adopted by many nations, becoming a blueprint of international law that remains in operation today.

Ibn Saud: The Desert Warrior Who Created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by Michael Darlow and Barbara Bray, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2012, 598 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Ibn Saud: The Desert Warrior Who Created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by Michael Darlow and Barbara Bray, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2012, 598 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

This is an intriguing biography of the George Washington of Saudi Arabia, Ibn Saud, who rose to become the leader of the oil-rich country. From his humble beginnings as a nomad, Saud demonstrated a keen interest in the politics of his country. As a guerrilla fighter and tactician, he had few equals. Within a few years, his army had doubled the size of the country and had seized the holy city of Mecca. In the early 1930s, the charismatic desert warrior consolidated the territories and became king of Saudi Arabia. When oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1938, Saud used his newfound wealth to convince nomadic tribes to abandon their raiding and wars against each other and unite. He would father more than 40 sons, the third of whom, Prince Faisal, would become king in 1964 and rule until 1975.

The authors have penned a timely book that is relevant today. As they point out, Saudi Arabia now controls one-fifth of the known oil reserves in the world. That gives the country an important position in global affairs. But, as the authors write, if that oil suddenly vanishes, will Saudi Arabia have diversified itself to maintain its influential standing on the world stage? If not, the Arab kingdom that Ibn Saud helped shape might well crumble under the pressure.

Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain’s Greatest Frigate Captain by Stephen Taylor, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2012, 320 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain’s Greatest Frigate Captain by Stephen Taylor, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2012, 320 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Edward Pellew, the first Viscount Exmouth, was arguably Great Britain’s greatest admiral in the 18th and early 19th centuries. A peer of Horatio Nelson, the best known of England’s naval heroes, Pellew had many friends and not a few enemies. Growing up in modest circumstances on the Cornish coast, Pellew rose through the ranks and was promoted to rear admiral in 1804. His defeat of the Barbary pirates in Algiers in 1816 with a combined English and Dutch fleet made him a national hero after that victory freed more than 1,000 Christian slaves.

Described by some as rude, boisterous, and impudent, Pellew nonetheless was generally considered to be the greatest sea officer of his time because of his leadership and ingenuity as a seaman. The author tackles the question of comparing Nelson and Pellew, describing it as interesting but misguided. “Whatever Nelson’s genius as a commander, it was his death and the manner of it that made him a quasi-religious figure, beyond comparison or criticism,” Taylor writes. Pellew didn’t die in combat, but his gallantry on the high seas, especially in his defeat of the Barbary pirates at Algiers, was legendary in itself, making him, as Taylor says, one of Great Britain’s ablest naval officers.

Service: A Navy SEAL at War by Marcus Luttrell with James D. Hornfischer, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2012, 365 pp., photographs, $27.99, hardcover.

Service: A Navy SEAL at War by Marcus Luttrell with James D. Hornfischer, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2012, 365 pp., photographs, $27.99, hardcover.

Former U.S. Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell has written a riveting account of his service in Iraq and Afghanistan, particularly during the disastrous Operation Redwing when his SEAL team was inserted near the Sawtalo Sar Mountains in June 2005 and ambushed by Taliban insurgents. Of the four-man group, only Luttrell survived. After recuperating from his wounds, Luttrell returned to combat duty and joined SEAL Team 5, where he spent six months in Ramadi during the intense house-to-house fighting there. He later received our nation’s second highest award for valor, the Navy Cross.

After leaving the Navy, Luttrell pondered why such men volunteer for hazardous duty and offer their lives for their country. He showcases some of his comrades who exemplified this warrior tradition, including his twin brother, Morgan, who is also a SEAL. Luttrell has paid fitting tribute to today’s fighting forces, men who risk their lives every day while serving in Afghanistan.

Reminiscences of Conrad S. Babcock: The Old U.S. Army and the New, 1898-1918 edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2012, 152 pp., maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Reminiscences of Conrad S. Babcock: The Old U.S. Army and the New, 1898-1918 edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2012, 152 pp., maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

The diary of Brig. Gen. Conrad S. Babcock provides readers with a glimpse of the U.S. Army prior to its entry into World War I and how it was transformed from a comparatively small force to a modern army. Babcock graduated from West Point in 1898. With the defeat of the Spain in the short-lived Spanish-American War, the U.S. acquired Cuba, Guam, and the Philippines and was propelled onto the world stage. Babcock was assigned to the Philippines during the insurrection that pitted American troops against the Filipinos insurgents fighting for their independence. During World War I, he was a regimental commander of the 28th Infantry and fought at the first and second Battles of Soissons. He retired in 1937 and died in 1950.

Babcock’s journal lay in obscurity at the Hoover Institution in Palo Alto, Calif., until it was discovered by Ferrell while he was writing about the Meuse-Argonne campaign. He has inserted notes at various points in Babcock’s memoirs to aid the reader. A keen observer of military tactics, Babcock’s manuscript is a valuable work in assessing how the U.S. Army moved from small-unit tactics to large-scale operations in “the war to end all wars.”

Promotion or the Bottom of the River: The Blue and Gray Naval Careers of Alexander F. Warley, South Carolinian by John M. Stickney, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2012, 186 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Promotion or the Bottom of the River: The Blue and Gray Naval Careers of Alexander F. Warley, South Carolinian by John M. Stickney, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2012, 186 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Much has been written about the Southern-born officers in the Union Army resigning their commissions when the Civil War started in 1861. Little, however, has been said about those Southerners in the Union Navy who chose to give up their blue uniform for a gray one. One such individual was Alexander F. Warley, a fire-eater from South Carolina (he was court-martialed four times in the Union Navy) who went on to have an illustrious, albeit short-lived, career as a Confederate naval commander. He reached the pinnacle of his success when he was given command of CSS Manassas, the first ironclad to see combat, during the Battle of New Orleans in 1861. After the war, Warley and his family relocated to New Orleans, where he died in 1885 at the age of 72.

The author does a good job of tracing Warley’s eventful life, gleaning information from ship’s logs, journals, and other historical archives to give readers a lively, accurate account of a relatively unknown naval officer who fought gallantly for the Confederate cause.

The Browning Automatic Rifle by Robert R. Hodges, Jr., Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 80 pp., photographs, illustrations, index, bibliography, $17.95, softcover.

The Browning Automatic Rifle by Robert R. Hodges, Jr., Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 80 pp., photographs, illustrations, index, bibliography, $17.95, softcover.

The Browning Automatic Rifle, simply known as the BAR, was one of the most innovative rifles to emerge in the waning days of World War I. It provided an infantry squad with the blistering automatic rifle fire of a machine gun with the accuracy and portability of an infantry rifle, by utilizing a 20-round or 40-round magazine. Between the world wars, U.S. Marines found the firepower of the BAR valuable when battling insurgents in Haiti, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, and China. World War II saw the BAR’s popularity rise among Army and Marine units. In the mid-1950s, the BAR was retired by the military after nearly 40 years of faithful service.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments