By Mason B. Webb

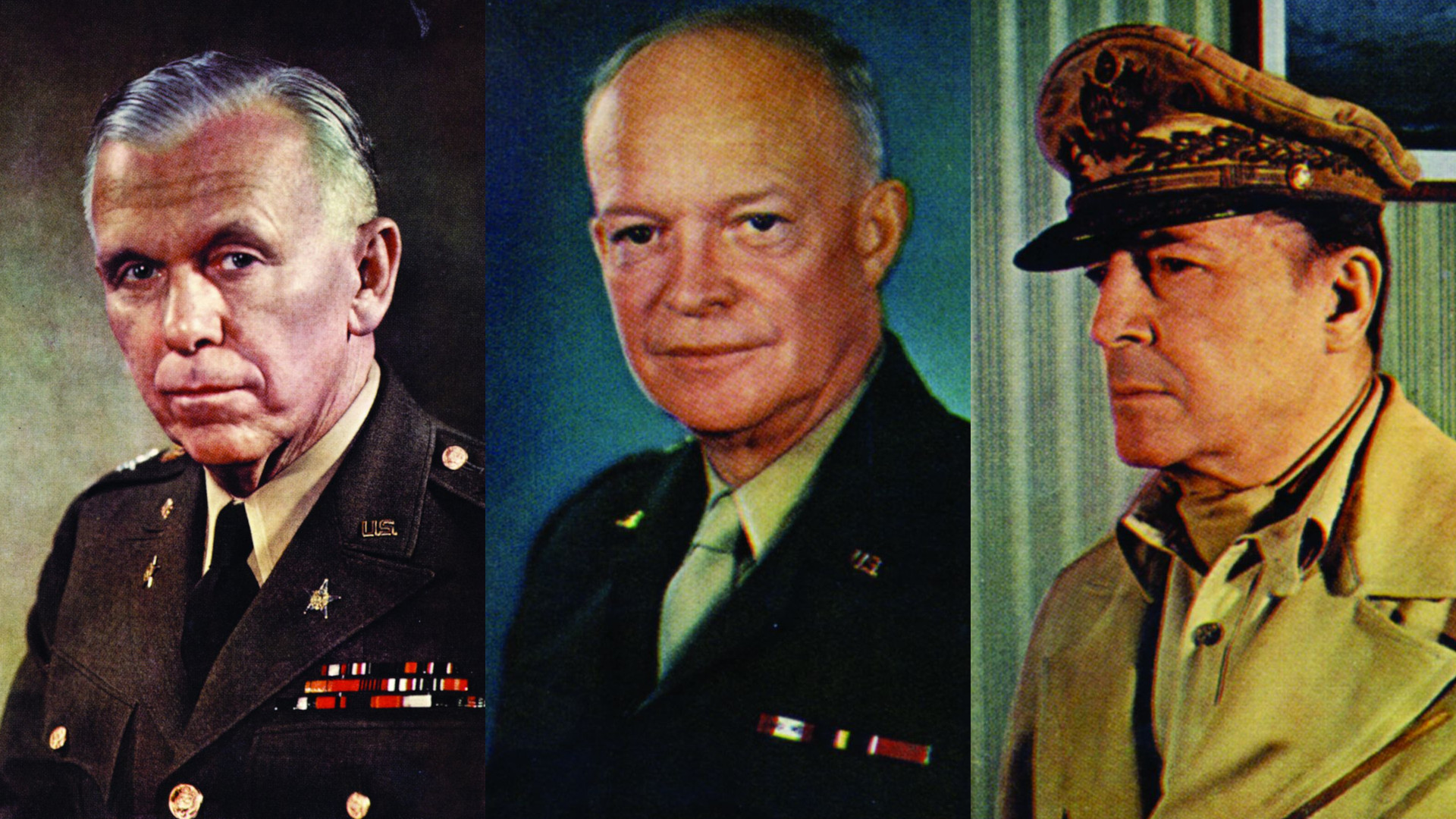

Only five modern American Army generals have ever been authorized to wear the five stars denoting the rank of General of the Army. Three of them—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur, and George C. Marshall—have been captured in 15 Stars: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Marshall—Three Generals Who Saved the American Century (Free Press, New York, 2007, 541 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $30.00), a fascinating multi-biography by the esteemed historian Stanley Weintraub.

So famous were these three men that, as the author writes, all three “were each featured on the cover of Time [magazine], when that accolade, in a pre-television era, confirmed a sort of eminence. All three would appear on postage stamps evoking their signature traits. Their immediately recognizable faces were remarkable indices of personality. MacArthur’s hawklike gaze conveyed his headstrong, contrary tenacity. Marshall’s seamed, inscrutable look suggested the austere middle America portraits by Grant Wood. Eisenhower’s ruddy, balding head and familiar grin brought to mind less the Kansas of his boyhood than the Everyman which admirers always saw in him.”

So famous were these three men that, as the author writes, all three “were each featured on the cover of Time [magazine], when that accolade, in a pre-television era, confirmed a sort of eminence. All three would appear on postage stamps evoking their signature traits. Their immediately recognizable faces were remarkable indices of personality. MacArthur’s hawklike gaze conveyed his headstrong, contrary tenacity. Marshall’s seamed, inscrutable look suggested the austere middle America portraits by Grant Wood. Eisenhower’s ruddy, balding head and familiar grin brought to mind less the Kansas of his boyhood than the Everyman which admirers always saw in him.”

In a narrative that weaves the lives of these three generals together—from their early beginnings, their entry into the Army through West Point (in the case of Eisenhower and MacArthur) and the Virginia Military Institute (Marshall), and their careers that intersected, diverged, then intersected again during World War II—Weintraub deftly handles what could have become a morass in the hands of a less skilled author.

As Weintraub points out, World War I forged the unique character of each man, and each man brought his own style of leadership to the task at hand during the second global conflict.

Here is MacArthur, vain and egotistical, yet brave and uncompromising; Ike, friendly, genuine, self-effacing, yet fiercely driven to hold a shaky coalition together and overcome a negative perception that his British allies had of him; and Marshall, cold, aloof, yet quietly efficient and trust-inspiring. Each man would stamp his own personality on the job he was called upon to perform, and each would perform magnificently.

The three generals mentored and competed with one another in the 1930s, then cooperated (but also still competed) during their collective triumph in World War II. All three became harbingers of global peace once the conflict ended.

After the war, MacArthur became the benevolent dictator of Japan and helped her write a new constitution and rebuild her economy. Marshall, too, helped rebuild Europe through the Marshall Plan and oversaw the integration of West Germany into the community of peaceful nations, work that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. Eisenhower went on to become president of the United States and helped end the Korean War (which MacArthur, as the top U.N. general, nearly turned into a nuclear conflict with Red China) while simultaneously arming the nation to confront the threat posed by the Soviets.

A highly satisfying and intriguing work that every history buff will find of interest.

Mussolini and His Generals: The Armed Forces and Fascist Foreign Policy, 1922-1940, by John Gooch, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2007, photographs, index, bibliography, 650 pp., $35.00, hardcover.

Mussolini and His Generals: The Armed Forces and Fascist Foreign Policy, 1922-1940, by John Gooch, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2007, photographs, index, bibliography, 650 pp., $35.00, hardcover.

Hundreds of books have been written about Adolf Hitler, the Nazi Party, and German foreign policy, but, surprisingly since Hitler obtained many of his ideas about fascism from Mussolini, very little has been written about the inner workings of Benito Mussolini’s state.

Fortunately, that glaring gap has finally started to be filled with the publication of John Gooch’s monumental, 650-page Mussolini and His Generals. This work is the first English language study to detail the military policies pursued by Fascist Italy, setting them in the context of the foreign policy advanced by Il Duce during this period. Unlike other recent books on Mussolini, this one is primarily a military history that explores the invasion of helpless Ethiopia and the failed operations against the British in North Africa, and not a biography or a look at life under fascism.

By the time Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, Mussolini had been the leader of Italy for more than a decade. He had been successful improving the Italian economy and bringing stability (albeit with heavy-handed policies) to a country wracked by economic collapse and internal turmoil and was seen as Italy’s savior by a large majority of the Italian populace. Mussolini’s ambition was to regain for his nation the power and prestige once enjoyed by the Roman Empire, things that Hitler also sought to achieve.

Ever since the inglorious collapse of fascist Italy following the Allied invasion in September 1943, the goals and achievements of Mussolini have been the subject of many studies and debates. Some historians see Mussolini as a buffoonish, inept, and power-hungry dictator whose chosen path to his goal was violence and absolute control, lacking effectual leadership once accomplished, while others have characterized him as a skilled leader who sought to create an Italian empire, but misguidedly allied himself with the genocidal madman Hitler.

Gooch, a professor of history at the University of Leeds in England, shows that while Mussolini bore ultimate responsibility for Italy’s fateful entry into World War II, his generals and admirals shared the blame for policies that all too often rested on irrationality and incompetence. Mussolini and His Generals is an important book for anyone who wants to understand more about the roots of mankind’s most devastating war.

Flights into History: Final Missions Retold by Research and Archaeology, by Ian McLachlan, Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire, U.K., 2007, 224 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $36.95.

Flights into History: Final Missions Retold by Research and Archaeology, by Ian McLachlan, Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire, U.K., 2007, 224 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $36.95.

During wartime, a family can receive no more devastating news than that a loved one is missing in action. Death, while emotionally painful to the survivors, at least brings closure to the family, whereas the designation of “missing in action” and the “subsequent lack of information only exacerbated their misery,” writes author Ian McLachlan.

His new book focuses on archaeological detective work that volunteer researchers have performed in an effort to solve the mysteries surrounding long vanished aircraft and airmen. Flights into History relates the fate of 14 flights undertaken by British, American, Belgian, and German airmen.

Some of the stories in the book (accompanied by more than 100 photos) record the final flights of aircraft that have disappeared forever, with only tiny fragments or mangled pieces of wreckage surviving. Archaeological evidence is, in many cases, all that now remains of proud aircraft that once soared into the skies, lifting high the hopes and spirits of young men who took them into battle.

Decades later, these wrecks and relics can reveal their secrets to the expert investigator, and their excavation and preservation can serve as monuments to the bravery of their crews, not to mention healing some of the emotional wounds of those left behind.

McLachlan’s book demonstrates how, by reconstructing wartime events from evidence in the wreckage, eyewitness accounts, and contemporary documentation, aviation archaeologists are able to identify the flyers involved and shed new light on the air battles that took place in the skies above Europe. A superb salute to those who gave their lives anonymously for their countries.

Forgotten Raiders of ‘42: The Fate of the Marines Left Behind on Makin, by Tripp Wiles, Potomac Books, Inc., Dulles, VA, 2007, 169 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $23.95.

Forgotten Raiders of ‘42: The Fate of the Marines Left Behind on Makin, by Tripp Wiles, Potomac Books, Inc., Dulles, VA, 2007, 169 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $23.95.

One of the most tragic yet least known episodes of World War II is what happened to a group of U.S. Marines who took part in the 1942 commando raid on Japanese-held Makin Island.

The raid began on August 8, 1942, when two companies of Marines, 211 hand-picked men commanded by Colonel Evans F. Carlson, along with President Roosevelt’s son, Marine Major James Roosevelt, crammed themselves into two giant submarines, the Argonaut and Nautilus, and headed for Makin Island.

Their mission was to create a diversion and siphon off enemy units that could be used to resist the 1st Marine Division, which had just landed on Guadalcanal, nearly a thousand miles to the south.

The raid, a morale boost for the Navy and the American public, which had endured a steady diet of bad war news for eight months, was hailed at home as a smashing success, and made Carlson, his Raiders, and Major Roosevelt national heroes. The truth, however, was something else. The raid was less successful than had been publicly reported, and, in the chaos that developed as the Marines reboarded their rubber rafts under enemy fire on the night of August 17 and returned to the subs lying offshore, nine Marines were inadvertently left behind.

Their fate was not pretty. Taken to the Japanese stronghold on Kwajalein, the nine blindfolded Americans were ceremoniously beheaded on October 16, 1942, by their captors.

After recounting the details of the dramatic raid, author Wiles focuses on the Raiders’ withdrawal from Makin and on Carlson’s decisions that directly affected the men who were left behind. Wiles also examines the actions, inactions, and conditions that led to the nine Raiders’ unintentional abandonment.

Finally, he reviews the Navy’s private reactions and, using new documents and interviews, the Raiders’ fate, bringing an end to the final chapter in the story of the disappearance and execution of the forgotten Raiders of ‘42. A thoroughly engrossing and moving book.

Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, by Spencer F. Wurst and Gayle Wurst, Casemate Publishers, Drexel Hill, PA, 2007, 266 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, by Spencer F. Wurst and Gayle Wurst, Casemate Publishers, Drexel Hill, PA, 2007, 266 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $32.95.

There is something about stories by paratroopers and about airborne operations that is of continual fascination to the reading public. It seems that history buffs just cannot get enough of the exploits of derring-do by raiders from the sky. To feed this never-ending hunger for airborne stories comes a remarkable book by Spencer F. Wurst, a member of the 82nd “All-American” Airborne Division.

Wurst (with a little help from his niece Gayle) has crafted a fine memoir about what life was like in the prewar Army. He enlisted in his local National Guard outfit in 1940, when he was just 17, subsequently enduring airborne training and time in combat.

Wurst made three of the regiment’s four combat jumps, dropping into Italy, Normandy, and Holland; the only one he missed was Sicily. Recalling the drop into Ste. Mère Eglise, Normandy, Wurst, a squad leader, writes, “To my surprise, there were fires in the town. Almost immediately after—these things happen in microseconds—I started receiving very heavy light flak and machine gun fire from the ground. This was absolutely terrifying. The tracers looked as if they were actually coming up at an angle. Many rounds tore through my chute only a few feet above my body.”

Wurst also remembers being puzzled by explosions below him as his fellow paratroopers descended. At first thinking the Germans were zeroing in with artillery on the 505th’s drop zone, he quickly realized that “these explosions resulted from our mine bundles. Either the speed of the plane pulled the chutes [of the bundles] off, or the bundles dropped faster than expected, and the impact bent the safety clips on the fuses, causing them to explode.” Shortly thereafter, he was wounded, but not badly enough to keep him out of further action.

After a month battling through the hedgerows of Normandy, he was wounded again, yet recovered in time to take part in Operation Market-Garden, where he and his unit were swept up in the fierce fighting against SS troops for the highway bridge at Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

One reviewer wrote, “Wurst’s book ranks as one of the best war memoirs written by a World War II veteran. Highly recommended.”

We concur. Filled with unforgettable tales of combat as seen from the perspective of a very lucky paratrooper, Descending from the Clouds is hard to put down and is destined to become a classic of World War II literature.

Stalingrad: How the Red Army Survived the German 0nslaught, by Michael K. Jones, Casemate Publishers, Drexel Hill, PA, 2007, 270 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Stalingrad: How the Red Army Survived the German 0nslaught, by Michael K. Jones, Casemate Publishers, Drexel Hill, PA, 2007, 270 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Stalingrad has always been portrayed as one of the pivotal battles of World War II, and now comes a book that portrays all the grim realties of that immense struggle in a new and revealing light.

Using a considerable amount of eyewitness testimony from Russian veterans and fresh archival material from war diaries and official unit histories, Michael K. Jones offers a radical new interpretation of this famous, almost mythical battle that lasted from August 1942 until February 1943 and resulted in 1.5 million combined casualties. His compelling account gives refreshing insight into the thinking of the Soviet command and the mood of the ordinary Red Army fighters.

Jones, known for his innovative and controversial studies of warfare, focuses his story on the Russian 62nd Army, which began the campaign in a state of utter demoralization, yet bravely held off savage attacks by the powerful German Sixth Army, an army which Hitler boasted could storm the gates of heaven itself.

As he recounts the course of the battle and seeks to explain the Red Army’s extraordinary performance in inhuman winter conditions and under unrelenting German fire, Jones uses a novel approach—battle psychology, emphasizing the vital role of leadership, morale, and motivation in an eventual triumph that many historians have called the turning point of the war.

Working from extensive interviews with veterans such as Anatoly Mereshko, a staff officer to the 62nd Army’s commander, General Vasily Chuikov, Jones presents considerable new and startling testimony about the battle. These accounts show that the oft-repeated stories of Stalingrad’s two most crucial days—September 14, 1942, when the Germans broke into the city, and October 14, when von Paulus’s men launched a massive attack on the factory district—disguise how really desperate was the plight of the defenders. In their place was a far more terrifying reality.

Understanding this, Jones shows the reader that Stalingrad was more than simply a victory of successful tactics but rather, despite overwhelming odds, an astounding triumph of the human spirit. Very highly recommended.

The Killing Skies: RAF Bomber Command at War, by Simon Read, Spellmount Publishing, Gloucestershire, U.K., 2007, 232 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00.

The Killing Skies: RAF Bomber Command at War, by Simon Read, Spellmount Publishing, Gloucestershire, U.K., 2007, 232 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00.

Long before the United States entered World War II and added the considerable weight of its bombs on German targets, the British Royal Air Force Bomber Command carried the heavy end of the stick against the enemy. While much has been written about the U.S. Eighth Air Force’s role in the war against Germany, Americans know little about the RAF Bomber Command’s contributions. The Killing Skies corrects that knowledge void.

Simon Read, whose grandfather flew on 51 combat operations over Nazi Germany, tells the story well. Currently a reporter for a San Francisco newspaper, Read has captured exactly the bravado and the fear that accompanied every mission into the killing skies. Expertly weaving between official reports and the air crewmen’s personal remembrances, he tells the story vividly, as though he had been there.

Read takes the reader along on mission after mission as the RAF switched to night bombing of German urban and industrial centers after daylight bombing proved too costly in terms of men and machines. Facing the ravages of marauding enemy night fighters and freezing temperatures that made skin stick to metal and coated their Lancasters and Wellingtons and Whitleys with thick sheets of ice, thousands of young British and Commonwealth pilots and crews performed their duty with unusual zeal.

Since the end of the war, Bomber Command’s efforts to destroy Germany’s means and will to continue the fight have been vilified by many as mere acts of wanton terror and destruction. To this day, the veterans of Bomber Command remain without a campaign medal, while present-day critics who did not themselves live through the terrifying “Blitz” equate the veterans’ actions with those of war criminals. This book shows that not only was the bomber offensive necessary for Britain’s survival, it also played a vital role in the ultimate Allied victory.

As Read points out, “It is impossible to argue that Bomber Command’s actions were not brutal, but to categorize the campaign as simply a means to terrorize the German populace is to ignore the greater context of the times in which it was waged.”

Of the more than 125,000 airmen who flew with Bomber Command, 55,573 died and 8,403 were wounded along the treacherous aerial road to victory. Read’s book is a magnificent memorial to them.

The Tank Killers: A History of America’s World War II Tank Destroyer Force, by Harry Yeide, Casemate Publishers, Dreel Hill, PA, 2007, 338 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $16.95.

The Tank Killers: A History of America’s World War II Tank Destroyer Force, by Harry Yeide, Casemate Publishers, Dreel Hill, PA, 2007, 338 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $16.95.

The tank destroyers battalions of World War II are a good example of the phrase, “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

The Allies learned early on that German panzers were virtually unstoppable, and weapons such as the 37mm and 57mm antitank guns were no more effective against superior enemy armor than peashooters. Even the Sherman- and Grant-mounted main guns were of little value against their heavier enemy counterparts.

At first, half-tracks were employed as TDs and equipped with 3-inch (76.2mm) guns, but the thin armor of the half-tracks made them unsuitable for crew longevity. A better solution needed to be found. That solution came in the form of the M10 Wolverine and, later, the M18 Hellcat, and M36 Jackson tank destroyers. The TD—basically a high-velocity gun in an open turret mounted on a tank chassis—was conceived to be light and fast enough to outmaneuver and hunt down Germany’s hard-to-kill panzers. Indeed, American doctrine stipulated that the TD’s primary role was to fight enemy tanks, while American tanks would concentrate on achieving and exploiting breakthroughs of enemy lines.

By the time the M36 reached the European Theater in September 1944, it sported a 90mm gun that could tear apart practically anything the Germans had to offer. The M36 was also used during the Korean War, where it again proved its value.

Very little has been published about American tank destroyers, however, which is one reason why Harry Yeide’s superb new book on the subject is such a welcome addition to the growing library of World War II subjects. Deeply researched and well written, The Tank Killers is a dramatic story of the role played by the U.S. Tank Destroyer Force in North Africa, Italy, and Europe, and the men who served in the TD battalions.

Yeide takes the reader through the organization and doctrine of the TD force, the training of the crews, and the continuing development of the vehicles and armament of the TD—changes required by the changing conditions of the battlefield and improvements in enemy armor. Yeide also goes into detail about the many engagements in which the TD battalions fought.

An excellent tribute to an arm of service that has for too long been overlooked.

Short Bursts

African American Troops in World War II, by Alexander Bielakowski, Osprey, Oxford, U.K., 2007, 64 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $17.95.

African American Troops in World War II, by Alexander Bielakowski, Osprey, Oxford, U.K., 2007, 64 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $17.95.

Although only 64 pages long, Bielakowski’s study of African American troops fills a wide knowledge gap about the contributions to victory made by the U.S. “colored” troops, as they were known then.

Half a million black American soldiers, sailors, Marines, airmen, Merchant Mariners, and Coast Guardsmen served overseas during the war, almost all of them in segregated, noncombat units. This stricture artificially limited their potential contribution, but their work, especially along the logisitic lifelines of the fighting divisions, was vital for victory.

Bielakowski’s book summarizes the service of these men and women; it also focuses on the relatively small proportion who overcame barriers of prejudice to reach the battlefield in combat units, such as the 92nd Infantry Division, 761st Tank Battalion, and the 99th Pursuit Squadron (the “Tuskegee Airmen”). Black troops also served with distinction in all theaters of war in segregated artillery outfits and as combat engineers, Seabees, medics, military policemen, and more.

Their story is illustrated with dozens of wartime photos and color plates, including portraits of some of the most outstanding individuals.

African American Troops in World War II is a fine book that is sure to open eyes to a class of brave and patriotic Americans who, despite the discrimination they faced at home, gave their all for their country.

The Library of Congress World War II Companion, edited by David M. Kennedy, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2007, photographs, maps, index, 982 pp., $45.00, hardcover.

If this massive tome had been titled Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About World War II, it would have been appropriate. Within its 982 encyclopedic pages, The Library of Congress World War II Companion covers virtually every World War II-related topic one can imagine, everything from the causes of the war, the main political figures, organization of the major Allied and Axis armed forces, weapons, major battles, propaganda, espionage, sabotage, war crimes, life on the home front, the aftermath, and much, much more.

As historian John Keegan has written, World War II was “the largest single event in human history,” and this book certainly portrays the wide variety of the experience—the ingenuity, industriousness, venality, sacrifice, brutality, and inspiring courage.

A writing team consisting of three senior writers/editors at the Library of Congress Publishing Office, and editor David M. Kennedy, professor of History at Stanford and a Pulitzer Prize winner, did a superlative job of putting together a volume that is at once both concise and detailed. The book is filled with intriguing facts, figures, sidelights, veterans’ memoirs, and excerpts from the private papers of some of the most famous personages of the day.

All in all, The Library of Congress World War II Companion is a tremendous and valuable reference that deserves to be on every World War II history buff’s bookshelf and will be used for many years to come. Worth at least double the $45.00 price.

Panzer Divisions: The Blitzkrieg Years, 1939-1940, by Pier Paolo Battistelli, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007, 96 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $23.95.

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Germany’s armored forces were still in their infancy. The restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles meant that German tank production lagged behind that of its enemies, but Hitler, as the world knows, was not one to be restricted by treaties. Soon Germany began turning out vast numbers of highly sophisticated armored fighting vehicles.

Initial armor campaigns in Poland were not particularly successful, however, and it was obvious that major changes were needed before the invasion of France and the Low Countries could be mounted the following summer. In Panzer Divisions: The Blitzkrieg Years, 1939-1940, Pier Paolo Battistelli examines the history, the organizational changes, developments in doctrine and tactics, and improved command and control that provided the basis for the spectacular success of Blitzkrieg, or lightning war, in 1940. Achieving tactical and operational surprise, the panzer divisions broke through enemy defenses, enveloped British, French, and Polish forces at Dunkirk, and pushed all the way to Paris and the Cotentin Peninsula. The legend of the Blitzkrieg was born.

Filled with photographs, charts, and maps, plus analytical descriptions of the various operations in which panzers were so effectively employed, Panzer Divisions is an invaluable resource for anyone with an interest in armor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments