By Eric Hammel

The seesaw land, air, and sea battles on, over, and around desperately contested Guadalcanal island had been raging since August 7, and still there was no victor. Now, in mid-November 1942, the Japanese and Americans both were racing to build up their respective forces in the area for what both intended to be the final confrontation. Despite the fact that the Imperial Navy generally controlled the narrow waters adjacent to Guadalcanal, the U.S. Navy had no choice but to throw everything it had into transporting fresh ground troops and a massive infusion of war materiel onto the island. The outcome would likely come down to which side could get there first, with the most.

Early on the morning of November 12, Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner’s Task Group 67.1—four troop-laden transports, plus escorts—closed on Guadalcanal’s Kukum village, just west of Lunga Point. All the transports anchored and immediately began unloading troops of the U.S. Army’s 182nd Infantry Regiment into their own boats. Accompanying the transports were destroyers and light and heavy cruisers intent on protecting the supply ships from submarines and air attacks.

The unloading operation proceeded without a hitch until 1:15 in the afternoon, when the radio station ashore warned the flotilla that a large force of Imperial Navy aircraft would be arriving over Guadalcanal in 15 minutes. This news had come from Lieutenant Paul Mason, an Australian coastwatcher manning a post high in the mountains of southern Bougainville. Although sought by Japanese patrols scouring the area, Mason and Paul Read, another coastwatcher manning a station overlooking Buka Passage north of Bougainville, had been providing accurate and timely information about Japanese air strikes and naval surface forces from the day the Guadalcanal action got underway.

As soon as the warning arrived, all the warships that had been dispatched earlier to fire on shore targets were recalled to screen the transports and cargo ships, which ended their unloading operation and got underway in two columns of three ships each surrounded by their array of warships.

The appointed moment came and went. Lookouts aboard all the ships strained their eyes to locate approaching aircraft, but there was nothing. At 1:50, a revised estimate was given: According to the radar station ashore, the Japanese strike group of about 30 warplanes was still 109 miles out and approaching from the northwest. It was expected over the fleet in 20 minutes.

In fact, there were 16 torpedo-laden Imperial Navy G4M Betty medium bombers escorted by 30 Zero fighters. They had completely buffaloed the Marine ground-control station and, by extension, the combat air patrol, which was at 29,000 feet looking for a high-altitude bombing raid when in fact the Bettys were approaching at low altitude. No sooner were the low-flying, twin-engine Bettys spotted by shipboard lookouts, however, than they disappeared behind Florida Island’s eastern cape, the Ass’s Ears.

Then they were back! Seconds after the destroyer Fletcher, the rearmost ship in the American screen, regained a radar fix on the Bettys, her gunners saw them as they popped out from behind Florida’s concealing bulk, sweeping up the wakes of the combined task force in a breathtaking line-abreast formation. Then the Betty formation split into two groups and started an attack at wave-top height. The nearer group flew in from the south while the other swung out to find a position to the north. Americans on the ships were universally awed by the fact that they could see foam streaming back behind propellers beating so close to the water.

Initially concerned with the nearer southern bombers, Admiral Turner first maneuvered his ships so that the fat transports showed their vulnerable sides to the Japanese bombardiers. When the southern Bettys were committed—moments after the fleet’s large-caliber antiaircraft guns opened fire at 2:12—the task force commander ordered an emergency turn to port, thus presenting the narrow, receding sterns of all his ships to the oncoming torpedo bombers.

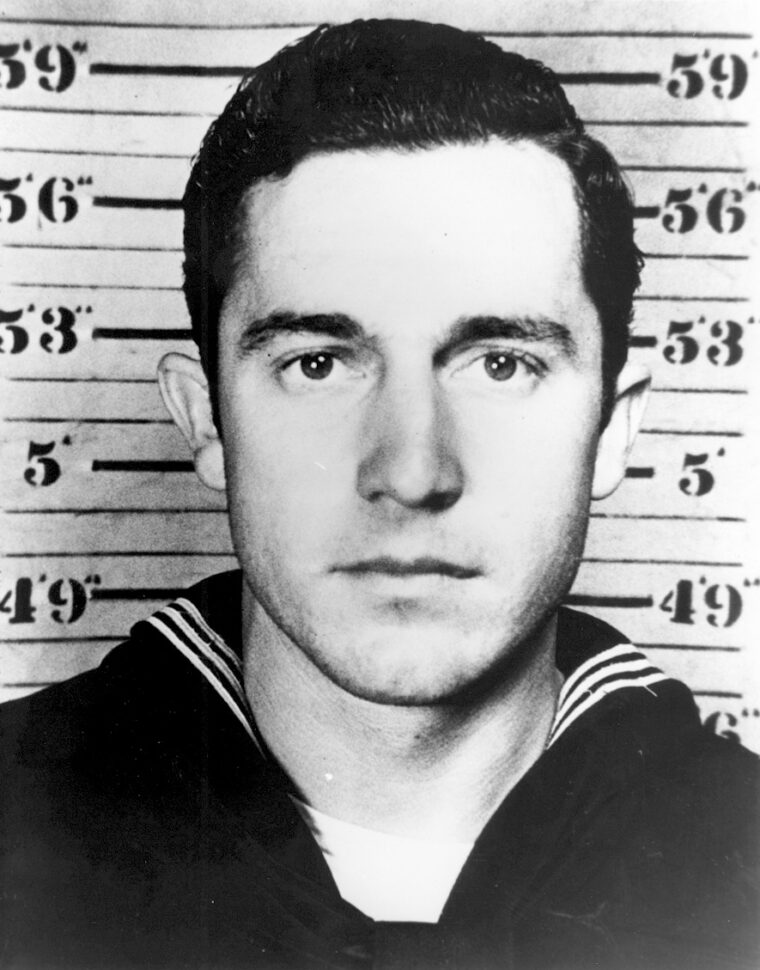

Seaman 1st Class Donald Dahlke, manning the Fletcher’s starboard midships 20mm gun, was able to get a clear bead on the nearest gray-green Betty of the southern bomber formation as it came up the starboard side from dead astern only 30 feet above the water. Dahlke had excelled as a gunner during practice drills, but this was his first opportunity to fire in anger. Everything clicked; all the training he had received in his 11-month naval career came together as he coolly fixed his gun’s ring sight on the glass bombardier’s blister at the nose of the cigar-shaped mid-wing bomber. A light burst of tracer—every fourth round—showed Dahlke that he was dead on, so he opened fire in earnest.

The swift destroyer, one of the newest in the U.S. fleet, was making full speed dead ahead, but the bomber was going more than 150 miles per hour faster as its pilot sighted a target ahead for the deadly 21-inch aerial torpedo slung in the open bomb bay. After each short burst, Seaman Dahlke had to swivel the gun forward to regain his aiming point. Because Dahlke was firmly cinched into the 20mm gun’s harness, sighting was effectively accomplished simply by moving his body to the right in order to carry the gun’s barrel to the left. Tracers were clearly entering the target between the bombardier’s nose blister and the flight deck.

A small, detached portion of Dahlke’s mind registered the fact that dark holes were appearing in the side of the passing bomber. Soon, he and others could see that the explosive rounds were literally chewing sections of metal from the airplane’s side. Then, after what seemed like hours, Dahlke’s gun ran out of space forward. Without hesitating, and with no curiosity whatever regarding his target’s fate, Dahlke swiveled his sights well astern in the hope of picking up yet another viable target.

The moment Don Dahlke turned away, most of the rest of the Fletcher’s topside crew saw the first Betty’s torpedo tumble end-over-end from the bomb bay. Then the Betty itself staggered and fell into the water, where it was consumed by a large ball of fire. Meantime, Dahlke found a second target and poured rounds into it much as he had the first. After only one brief burst, however, the second bomber pulled up to evade Dahlke’s accurate fire. Dahlke immediately noticed a third airplane out of the corner of his eye as it came nose-on right up the Fletcher’s wake. Just as Dahlke got his sight on the dangerous intruder, it dawned on him that he was about to open fire on a friendly but out-of-place Marine F4F Wildcat fighter. Several rounds left the gun before Dahlke could overcome his reflexes, but the Wildcat streaked by, apparently without ill effect.

The two heavy cruisers in the channel, the Portland and the San Francisco, attempted a novel experiment aimed at fouling the oncoming bomber formations. Minutes after her 5-inch secondary battery began putting out rounds aimed at directly destroying the Japanese bombers, the Portland unleashed a six-gun main-battery salvo. The improperly fused 8-inch rounds were hardly capable of destroying an airplane, except perhaps by scoring an accidental direct hit, but the Portland’s main-battery officer was not looking for a direct hit. His objective was to put up a solid wall of white water directly in front of the low-flying Bettys. If his aim was true, the 8-inch detonations might throw off the aim of the bombardiers, or perhaps even cause a Betty to crash.

The experiment was noble, but getting the large rounds to land just right was more a matter of luck than skill. The first six rounds fired were of the armor-piercing type normally carried in the big guns in these waters. These did not make a big enough splash, so the second salvo was six high-capacity bombardment rounds. These made the desired big splash, but they did not land in quite the right spot at quite the right moment, and all the Japanese bombers breasted the white-water tide without being appreciably jarred from their course. The San Francisco’s main battery attempted the same trick, but it had the same results; the guns were fired a bit too early or a bit too short, so the wall of water had receded by the time the Bettys arrived. Moreover, the lighter antiaircraft weapons aboard both heavy cruisers were handicapped by the enormous amount of smoke that was a byproduct of the main-battery salvos.

The well-practiced gunners aboard the cargo ship Betelgeuse, the last ship in the right transport column, picked up a Betty as it bored in from the port quarter. While the 3-inch guns continued to fire, the cargo ship’s 20mm gunners had to watch and wait until the attacker flew into range. As soon as the 20mm cannon opened fire, the Betty staggered in its course only 300 yards from the ship and precipitously veered to the left. It crashed into the water only a thousand yards from the Betelgeuse.

Within two minutes, two more Bettys were observed as they closed on the Betelgeuse from directly astern. Both targets were coming steady on at only 60 feet—easy, stable, no-deflection targets for the cargo ship’s stern 3-inch gun. One proximity-fused round burst beside both planes and sent both Japanese pilots careering from their course. Both planes dropped their torpedoes from 1,500 yards. The starboard Betty’s torpedo was clearly visible to Commander Harry Power, the Betelgeuse’s captain, as it momentarily hung by its tail and plunged into the water at an angle of about 60 degrees. As soon as the torpedo nosed into the water, it was bounced clear off the surface by the force of its momentum, then nosed back into the water and disappeared. Once both torpedoes were away, the Bettys diverged to pass up each side of what had until then been a relatively silent ship. As they came even with the cargo ship at a height of about 50 feet, their wingtips were no more than 75 feet out. In addition to fire from the five hitherto silent 20mm cannon mounted on each side of the ship, both Bettys were suddenly subjected to gunfire put out by scores of infantry weapons in the hands of Marine aviation engineers still embarked.

The starboard Betty began to burn as it came even with one of the midships hatches, and it was a mass of flames by the time Commander Power saw it come even with his flying bridge. Nevertheless, it was still able to put up a fight. The Japanese airman manning the Betty’s waist 7.7mm machine gun returned the Betelgeuse’s fire, and bullets struck the gunner, loader, and assistant loader of a starboard 20mm gun. The Betty then crashed into the water about a hundred yards off the Betelgeuse’s starboard bow, thus obliging Commander Power to order the rudder put over hard left and then hard right to keep the ship from running over flames that were higher than her masts.

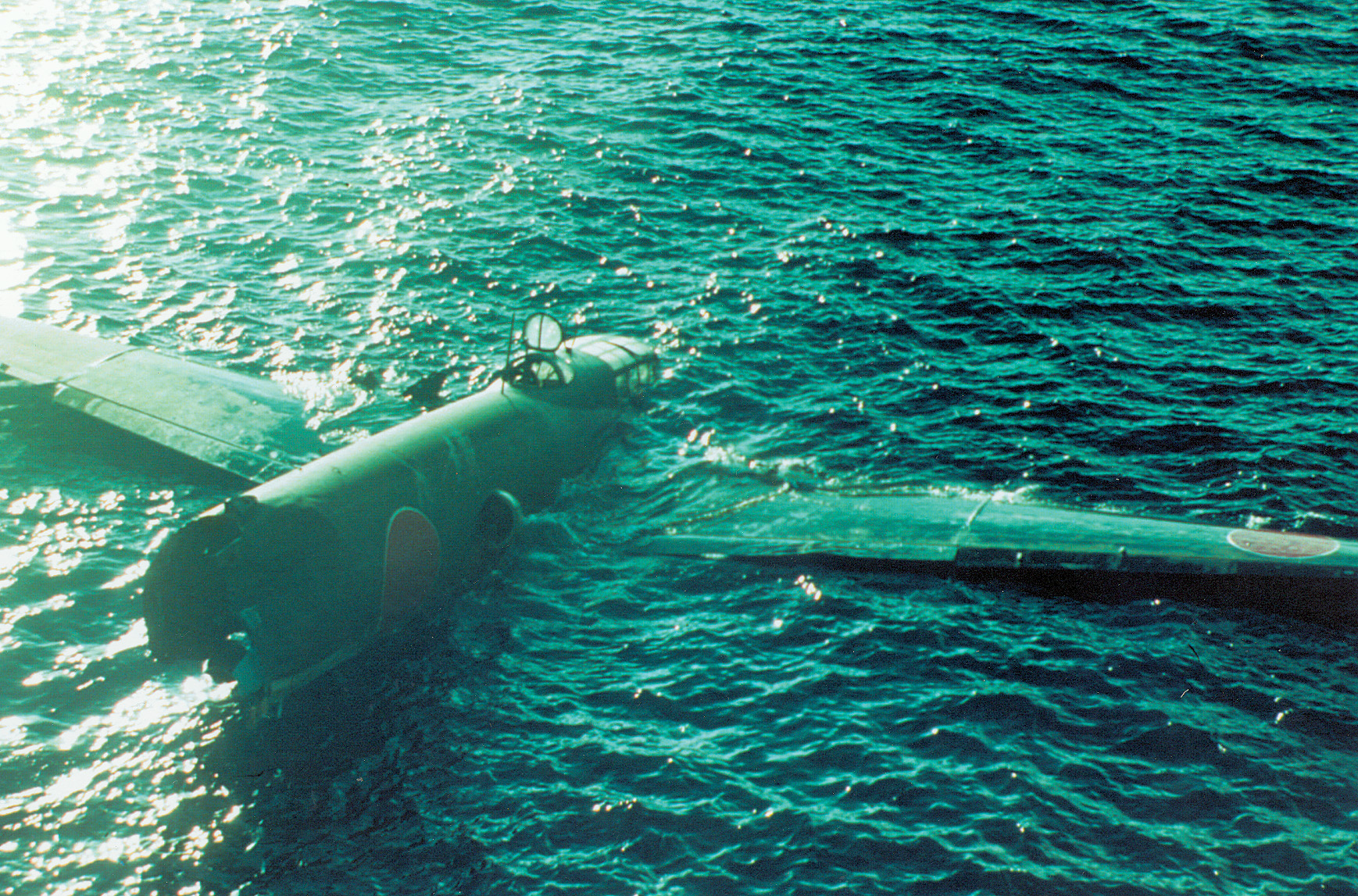

At the same time, massive gunfire ignited a fire beneath the starboard wing of the Betty passing up the Betelgeuse’s port side. Tracers could be plainly seen as it entered the cockpit area, and the plane soon appeared to be out of control, either due to damage to the controls or injury to the pilot. The Betty swerved across the bow from port to starboard and pancaked into the water, where it sank to the top of its fuselage. It was still afloat when last seen from the passing cargo ship. In addition to causing minor material damage, the Betty gunners had wounded six Betelgeuse crewmen and seven Marines.

Only three Bettys came within machine-gun range of the transport Crescent City, the center ship of the left transport column. All three of them passed close aboard the port side. The transport’s topside crew saw only one of the Bettys drop its torpedo, which struck the water tail-first before skidding and diving from view. The transport’s guns clearly struck all three Bettys, as did those of numerous other ships on the far side of the surface formation. The lead Betty burst into flames as it passed the Crescent City’s fantail and fell into the channel moments later. The second plunged into the sea off the transport’s port beam, and the third overtook the formation before veering toward a beach near the Japanese-occupied western end of Guadalcanal. It crashed into the water well short of its objective.

The destroyer Laffey was approached by a lone Betty from the direction of her starboard quarter. Immediately all four of the destroyer’s 5-inch mounts trained out and locked on as the vessel’s master mechanism for finding and following targets, the gun director, did its work. As the 5-inchers opened fire, the 1.1-inch and 20mm guns followed suit, tracking the torpedo bomber from aft to forward as it attempted to retire to safety. Soon, the 5-inch mounts had swung all the way forward into their fixed stops, which had been placed to prevent the guns from firing into any structure on the ship itself. Unfortunately, the designers of the stops had failed to take other factors into account. As Mount-3 fired its last round after the departing Betty, the fireball of burning powder expelled through the barrel completely enveloped the 1.1-inch mount trainer, who was seriously burned from shoulder to waist.

The destroyer-minesweeper Southard’s 4.5-inch guns were able to bear on the dozen Bettys attacking from astern, but there were only five bombers remaining aloft by the time her guns could get a clear shot. When the bombers approached to within 2,000 yards, the Southard’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. John Tennent, ordered the rudder placed hard to port to give the guns on both sides of his ship an opportunity to fire. The move was hardly required since three of the Bettys swerved astern and passed directly over her fantail, thereby providing the ship’s 20mm and .50-caliber guns with superb targets. All three of these Bettys were struck by so many rounds from the Southard and nearby vessels that they fell burning into the channel within a thousand yards of the Southard.

Of the two remaining Bettys, one was struck by fire from the Southard’s machine guns as well as rounds from other ships. It crashed off one of Guadalcanal’s Marine-held beaches. The Southard had the last Betty in the group under fire when a Marine F4F fighter roared in from above, obliging the quick-witted gunners to cease firing. The Betty, which cartwheeled into the water 2,000 yards away, was credited to the Marine pilot.

The Marine combat air patrol—eight Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121) Wildcats led by Captain Joseph Foss—was late getting into the fray because it lost sight of the Bettys as they passed around a large cloud that hung 20,000 feet over Florida. The Bettys were still high enough to make Foss believe they would be launching a high-altitude bombing attack, so he kept his Wildcats tethered at 29,000 feet until the bombers reappeared and he saw that they were low and splitting into two attack groups. Because so much time had been lost, Foss had no choice but to put everything he had on the nearer northern formation. By then, the Bettys were passing below 500 feet.

“Put your engines on low blower,” the flight leader yelled into his microphone. “They’re coming in low. Let’s go get ’em, boys!” Then he pointed his Wildcat’s nose straight down at the far-distant Japanese flight leader’s bomber. The descent from the freezing upper atmosphere was so rapid that the insides of many of the Wildcats’ windscreens frosted over. Captain Foss, among others, had to scratch off the rime in front of his face so he could see through the windscreen again.

Captain Frank Clark, an Army Air Forces pilot at the controls of one of the eight 67th Fighter Squadron Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters that scrambled in response to news of the raid, also apparently had a problem with frost on his canopy. But unlike the Marine pilots, Clark was unable to clear his windscreen or, for some reason, control his dive. His P-39 was seen knifing straight into the water without ever making a move to pull up.

In the meantime, Major Paul Fontana’s ready group of eight VMF-112 Wildcats had been suckered by the high approach of the incoming strike group into a long, fruitless climb from the Fighter-1 dirt airstrip. While climbing leftward at 20,000 feet and about 10 miles north of Henderson Field to come on station as ordered by the ground fighter-control officer, Fontana was told that the Japanese formation had disappeared from radar and might be at low altitude to the south. Fontana obligingly dived to a lower altitude on a southerly heading and thus spotted the Japanese northern formation.

Following through on his long dive, Fontana racked up his second aerial victory of the war when he flew up to within about 50 yards of one of the bombers in the lead “vee” and opened fire. The Betty instantly caught fire and crashed into the water.

Careful to avoid the bursts of friendly antiaircraft fire that were by then reaching out toward the bombers, Fontana was just shifting his attention to a second Betty when his Wildcat was scoured from wingtip to wingtip by an unseen Imperial Navy Zero fighter. Full of holes, the sturdy Wildcat still barely staggered under the impact. Fontana put on full throttle as the faster-diving Zero screamed by and initiated a climbing turn to the left. Fontana nimbly moved inside the Zero’s turn and opened fire. The Wildcat’s six .50-caliber machine guns set the Japanese fighter ablaze, giving Fontana his second victory in as many minutes.

When Major Fontana’s second-section leader, 2nd Lieutenant William Wamel, first saw the Japanese bombers glide beneath his Wildcat’s left wing, he sang out “Tallyho!” on his radio and commenced a diving left turn to get in their tails. As Wamel steadied up in a shallow full-power dive right up the tails of the group of Bettys, he saw another gaggle of the Japanese medium bombers setting up a torpedo run at right angles to the shipping in the channel. Wamel slowly came up to within a half-mile of the nearest destroyer, but all the ships in the channel seemed to open fire right at him. Fearful of having to break away before getting his licks in, Wamel armed all six of his wing guns and fired a three-second burst, but he was far out of range. Suddenly, one of the Bettys blew up from an apparent direct hit scored by one of the ships, and seconds after that, Wamel’s fighter was rocked by a near miss that propelled several large slivers of shrapnel through the cockpit.

Shaken by the near miss, Wamel nevertheless ignored the output of the Betty’s 20mm rear cannon “stinger” and bored on up the bomber’s wake. He opened fire again when he knew he was well within range, but only one of the six wing guns worked. His speed carried him past his target. So he pulled out to the right and dumped speed to get back behind the Betty. It came to nothing. The throttle would not respond, so Wamel pulled away and headed back toward Guadalcanal. His only hope was to get over friendly territory before the Wildcat’s engine died.

The Wildcat carried Bill Wamel almost to the friendly beach, but he felt it give its last gasp well short of land, so he turned into the meager offshore breeze. Although Wamel’s Wildcat was one of the first to arrive at Guadalcanal equipped with a shoulder harness, Wamel had neglected to secure his—now it was too late. He also forgot to lower the landing flaps to slow the fighter. The combination of oversights was potentially fatal. Wamel’s dying Wildcat sliced into the surface at great speed, and the sudden braking action of the water pitched the pilot’s forehead into the gun sight. Wamel unfastened his seat belt and climbed out of the cockpit in one motion. He pivoted to the rear, took one step, and walked right into the water off the trailing edge of the wing. When he looked up, a landing boat was already bearing down on him.

Bill Wamel reached shore safely and had the cut over his eye sutured almost before his squadron mates returned. However, within several days, he had to be evacuated when an undisclosed concussion proved to be the source of some temporary but mighty erratic mood swings.

VMF-112’s 2nd Lieutenant Jefferson De Blanc, Lieutenant Bill Wamel’s wingman, got right on the tail of a Betty and smoked it with a solid burst. As the Betty burned, however, De Blanc came under the influence of target fixation. Staring through the gunsight reflected on his Wildcat’s windscreen and then through the spinning strobelike orb of the propeller, De Blanc was unable to tear his eyes away from the Betty. By the time he was able to yank free of the stunning vision, he was far beyond the fleet. He executed a hasty wingover and raced back toward the action in the hope of meeting another Betty head-on as it tried to escape the mayhem over the channel. He saw only one Betty emerge from the wall of antiaircraft fire surrounding the transports and their escorts, and it was heading straight for him.

Endowed with uncanny 20/10 eyesight, De Blanc was able to select an aiming point and open fire while at the maximum effective range of his fighter’s machine guns. Suddenly, the Betty’s left engine flared. Within seconds, the amazingly fast closing rate carried the Wildcat over the top of the bomber. At the last instant, De Blanc’s attention was arrested by motion in the bomber’s flight deck. He saw three people crowded into the tiny compartment, where the pilot seemed to be slumped forward and the standing man seemed to be struggling to pull him from the control yoke before the bomber nosed downward.

An instant after streaking by, De Blanc pulled a hasty wingover and came up astern of the bomber. He felt like a sitting duck for the 20mm tail gunner, but no fire came his way, because he could see the gun blister was empty. Somehow, the bomber disappeared from view. Jeff De Blanc was certain it crashed, but he did not see it go in and thus accepted credit for a probable victory.

The destroyer Buchanan was sailing between the San Francisco and the light cruiser Atlanta when her 5-inch guns opened fire on the northern formation of Bettys approaching from the starboard bow at a range of about 12,000 yards. The guns held the targets while the destroyer undertook a tortuous turn in company with the flanking cruisers. One of the Bettys crossed ahead of the Buchanan only a hundred yards away and 50 feet off the water. It curved back and dropped its torpedo at a point about 300 yards off the destroyer’s starboard bow. The torpedo was seen to fall cleanly into the water, but its wake was not observed as it passed ahead of the Buchanan because the entire topside crew was diverted by the burst of a misguided, friendly 5-inch shell. The friendly round holed the starboard side of the after stack, severely damaged the torpedo mount, and obliterated a 20mm machine gun along with its crew of three. In all, the round killed five and wounded seven. Seconds later, five 20mm explosive rounds fired from port struck the base of the torpedo mount and the mount-2 5-inch gun shield.

At 2:19, the Buchanan’s port machine-gun battery locked onto a Betty that was passing close aboard at 50 feet. As the Betty drew ahead, its 20mm stinger opened fire. Damage was nil, but a signalman on the port wing of the bridge was slightly injured by shrapnel. The main battery fired at this and other retiring Bettys as they flew ahead, and one of the 5-inch guns got a kill or an assist at long range.

The light antiaircraft cruisers Atlanta and Juneau should have been in their element that afternoon. They had been built specifically to take out bombers intent on wreaking havoc upon other ships. Each was armed with 16 5-inch guns mounted in eight dual mounts, up to seven of which could be trained to one side or the other at any time. Each ship’s main battery was augmented by four quad-1.1-inch mounts and eight single 20mm antiaircraft guns. Altogether, the Atlanta and Juneau were capable of putting an immense cloud of fused rounds in the path of the oncoming Bettys.

Unfortunately, the Atlanta was placed nearly in the center of the formation, and not on a flank, where her rapid-fire guns would have been given freer rein. As soon as the broad line-abreast Japanese bomber formation drew inside the outer ring of destroyers, Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Leighton Spadone, a seven-year Navy veteran commanding the starboard midships 1.1-inch mount located just below the bridge, constantly had to check fire and reacquire targets when the friendly ships he was trying to protect kept appearing in his sights. Other mount captains and the cruiser’s main battery director were experiencing the same difficulty, which cut into the Atlanta’s effective output of rounds.

Busy as he was guiding his mount onto enemy bombers while avoiding friendly ships, Spadone was consciously struck by the resolute bravery of the oncoming Japanese airmen, whom he felt knew they were facing certain annihilation.

Coxswain Ted Blahnik, a gun crew’s pointer controlling the light cruiser Helena’s starboard quad-40mm mount, had been waiting for months to lay his sight on a hostile target. Helena was a veteran of one naval surface battle, but the defense against the Bettys was her first antiaircraft action. Coxswain Blahnik got the word from Sky Control, the position high over the bridge from which the antiaircraft gunnery officer held forth, and had the nearest approaching Betty firmly in his sight within minutes. Once Blahnik was locked on target, the 40mm gun pointer matched bearings with his own sight and locked his control apparatus to the ship’s director; he would resume local control only if the director was disabled. Blahnik received “Open fire!” from Sky Control when the Bettys were 3,500 yards out. He coolly squeezed the trigger and watched the 40mm tracer rounds streak out toward the Betty he was holding in his sight. The well-practiced loaders in the gun tub beneath Blahnik’s position never missed a beat.

Suddenly, the stream of tracers stopped. Nonplussed, Blahnik looked around from his sight to see what was the matter. Wordlessly, the mount captain pointed to one of the transports. Blahnik had not noticed when the friendly vessel entered his mount’s cone of fire as he traversed the director and the mount.

In addition to the 40mm guns, the Helena fired her four dual-5-inch mounts and all the 20mm guns that could bear from positions along the main deck and throughout her superstructure. For all that, the light cruiser claimed only one sure kill and several assists or probables. Unfortunately, it was probably the Helena’s guns that fired the rounds that struck the destroyer Buchanan and killed five Americans.

Captain Joe Foss pulled out of his screaming dive within a hundred yards of a retiring Betty and fired a full burst into its starboard engine, which began smoking. The Betty pilot immediately moved to pancake his laden bomber in the water, but the right wing got low and the Betty cartwheeled and fell apart.

Foss’s momentum carried him through the formation of smoking Bettys and on toward the furiously firing warships, dead ahead. As Foss lined up on a fresh Betty, one of the Zero escorts streaked out of nowhere and delivered a high-side firing pass on Foss’s F4F. Extremely annoyed by the interruption, Foss reflexively pulled his sight up onto the passing intruder and downed it with a short burst. The bomber was still a possibility, so Foss pulled back onto its tail, careful to remain clear of the 20mm stinger’s cone of fire. Still somewhat shaken by the close encounter with the Zero, Foss did not pay careful enough attention to his shooting, and he missed the Betty. He next crossed over from right to left and fired a short burst into the left wing root, where one of the bomber’s volatile and unprotected main fuel tanks lay. Immediately, flames spread from the breached tank to the left engine. The doomed Betty eased into the water for a perfect flame-quenching landing. As Foss streaked by overhead, the bilged bomber’s dorsal-turret gunner put a burst into the Wildcat’s engine housing, but with no apparent effect.

The triple kill on November 11 brought Captain Joe Foss’s score to 22, making him the Pacific War’s highest-scoring ace and, so far, the second-highest-scoring ace in U.S. history.

Foss next went after yet another Betty, but he could not get in a killing shot before he was jumped by a pair of Zeros. He flew as low as he dared and streaked toward Savo Island—still on the bomber’s tail—as bullets from the Zeros’ guns foamed the water around him. Suddenly the Army Air Force’s P-39 piloted by 1st Lieutenant James McLanahan cut in front of Foss and poured fire from its two .50-caliber and four .30-caliber wing guns and single 37mm nose cannon into the bomber. The Zeros chasing Foss turned their attention to the overeager Army airman, who tenaciously clung to the Betty’s tail as it flew up into a cloud. By some miracle, McLanahan not only evaded the Zeros, he destroyed the Betty as well.

Joe Foss willingly dropped out of the fight when his .50-caliber ammunition boxes registered empty and he had to switch to his reserve fuel tank. As luck would have it, he came across an unengaged Betty. Almost tearfully, Foss tried to locate a friendly fighter on the tactical radio, but he could not talk anyone into going after the Betty. On the way back to Fighter-1, Captain Foss counted the remains of a dozen Bettys in the water.

Another VMF-121 pilot who finally made the charts was 2nd Lieutenant Jack Schuler. Schuler had been in plenty of dogfights during VMF-121’s inaugural combat tour at Guadalcanal, but he had never quite gotten a solid piece of any of the many Zeros with which he had tangled. In fact, the only perfect attack he had ever launched had come against a Betty at the very start of his combat tour. Despite the perfect firing run, however, he had drawn a blank; his new Wildcat’s new machine guns had balked because the thin layer of cosmoline they still hosted had frozen solid at altitude.

When Joe Foss peeled out over on the low-flying Bettys, Jack Schuler picked one out of the crowd and kept right on top of it during the long descent. Following the long vertical dive, in which his airspeed indicator showed he was traveling at more than 400 knots, Schuler’s big fear was that he was going to overrun the Betty he was tracking. He had plenty of time to ease out of the dive, but matching speeds was tricky business under the circumstances. Schuler could see smoke-shrouded ships flashing past in his peripheral vision, but it never quite registered that he was following the Betty through the middle of the fleet and its antiaircraft umbrella. His only concern beyond lining up on the Betty was keeping himself from running into a ship, for he was by then only 50 feet above the waves. It never entered his head that he might be downed by friendly fire put out by over-excited shipborne gunners.

Schuler got perfectly lined up behind the as-yet unwary Betty and came up very close on its tail. His mind’s eye clearly saw a human form in the Betty’s tail blister, but his thinking was lagging just a hair behind reality because of his adrenaline-induced high; he was acting and reacting faster than he knew what was going on. So, when the 20mm cannon ahead began winking out bullets, Schuler wasted a precious split second trying to decipher what appeared to him to be a signal-lantern message.

Instantly abashed by his error, Schuler peered through the gun sight reflected on his Wildcat’s windscreen and set the pipper on the bomber. It vividly occurred to Schuler that he had remained scoreless to this point partly because he had wasted ammunition on tricky snap shots. This time, he was determined, he would emerge from the fight with enough bullets left over to scythe a wide path of destruction through the Japanese formation.

The pilot’s trigger finger closed slowly on the trigger, and the guns burped out a brief burst, perhaps only six rounds apiece. The tracers converged perfectly on the 20mm gun blister, and tiny slivers of glass ballooned into the slipstream. As Schuler’s fighter slowly overtook the speeding bomber, and with the immediate danger overcome, he nudged the pipper a hair to the right, directly over the right wing root. Again he nudged the trigger and watched his tracer go in at just the right spot. Almost immediately, a thin wisp of flame shot from the shredded wing root. Schuler instinctively eased back the throttle a hair, just in time to give himself an extra margin of safety as the bomber blew up right in front of his propeller spinner. The large main section of the shattered fuselage plummeted into the water and broke into numerous smaller pieces, each trailing its own plume of smoke. From the main point of impact streamed a long smear of burning gasoline.

With the smell of blood in his nostrils, Schuler became a hunter as he had never been before. His head swiveled to cover the entire sky, questing after another potential victim. But the only Bettys he could see were strewn across the surface of the water. Many of them were whole, but none was airborne. Schuler chased back and forth across the channel in response to several radio reports pinpointing Zeros, but he kept finding empty sky.

The incredible bravery of the Japanese aviators persisted even after the bombers were downed. The destroyer Cushing came alongside one floating Betty to rescue a Japanese airman who was standing in the ankle-deep water on its wing. As the destroyer slowed, the Japanese airman pulled out a small pistol and fired at the 2,500-ton ship. Instantly, a 20mm gunner requested and received permission to return the fire. The 20mm had to be depressed almost vertically to bear on the Japanese, and there was a misfire. Shrapnel from the exploding 20mm round severed an artery in the arm of the loader, but a cook manning the single 20mm cannon near the destroyer’s bows cut the Japanese airman in half with a short burst.

In all, pilots and ships’ gun crews claimed 59 victories against the 16 Bettys and 30 Zeros that participated in the attack, obviously making claims on planes others had as well, or making claims on planes they had fired at but had not seen crash. Of the Bettys, only two returned to Rabaul, three reached the emergency airfield at Buin, and two force-landed off Guadalcanal. Of these survivors, not one Betty was deemed airworthy and all were scrapped. Only one Zero failed to return to Rabaul, stark testimony of their failure to enter the fray with gusto. Fierce must have been the words to the leader of these fighter pilots whose job was to protect the bombers, nearly all of which were destroyed.

At 2:15, gunners aboard Admiral Turner’s flagship, the transport McCawley, which was leading the left transport column, managed to disable one of the last of the passing Bettys. Hundreds of amazed spectators looked on in helpless dismay as the Betty lurched from its course and flew straight up the San Francisco’s wake. It wobbled toward Rear Adm. Daniel Callaghan’s flagship, dropped its torpedo alongside the heavy cruiser’s starboard quarter, and then pivoted inboard.

Seaman 1st Class George Murphy, a gunner’s mate striker serving as first loader on the starboard after 1.1-inch mount, could not see the oncoming Betty, but he thought the ship might be in trouble because of the mount’s angle of deflection and point of aim. But Murphy had no idea how grave the situation was about to become only 80 feet forward of his position. Behind Murphy, the Betty’s starboard wing passed directly over the head of Lieutenant Howard Westin, who was manning the after 1.1-inch battery director.

As a member of the cruiser’s aviation division, Seaman 1st Class William Boyce, a plane captain, had the run of the ship during general quarters. For this action, he had selected a vantage point amidships, near the scout-plane hangar. Boyce was one of many to spot the burning Betty as it curved toward his ship. He was certain it would overfly Battle-2, the emergency after battle station manned by the cruiser’s executive officer and a staff identical to the one manning the fighting bridge. If the Betty indeed overflew Battle-2, Boyce reasoned, it would come down in the vicinity of the volatile hangar. With that thought, Seaman Boyce began running aft to be as far from the hangar as possible when the Betty hit in a few seconds.

As the bomber’s starboard wingtip angled in over the cruiser’s after superstructure, it clipped Lieutenant (jg) Jack Bennett in the elbow and passed forward without inflicting more harm upon him. In another second, however, the wing collided with the cruiser’s after control station.

The Betty’s momentum carried it all the way around into the structure, where the force of the impact caused its fuel tanks to rupture. The impact alone demolished Control Aft, and the flames gutted Battle-2 as well as the after 5-inch antiaircraft battery director and the after radar-control station. The crews of the three 20mm cannon positioned on a platform surrounding the 5-inch director were incinerated as they continued to fire on the Betty during the last instant of its plunge into their ship.

The sailors manning the starboard after 1.1-inch mounts instinctively jumped away from their guns at the moment of impact. The gun trainer, who remained at his station, commanded the rest of the crew to re-man the weapon, but by then there were no more targets. By the time the crew had settled in, the mount captain, Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Reinhardt Keppler, was long on his way forward to help pull wounded and dead shipmates from the flaming structures.

Seaman 1st Class Willie Boyce was still running aft when the Betty struck. Fortunately, his momentum had just carried him beneath an overhang as the flaming aviation gasoline cascaded from above. Boyce stopped on a dime, hemmed in on all sides by walls of flame. As the gasoline continued to pour down, Boyce saw the bomber’s fuselage fall directly over the port side, where it finally came to rest in the water. One of many topside crewmen who hated to wear confining antiflash clothing in the tropical heat, Boyce was thankful to his toes that he had heeded the standing order this day. After taking as much heat as he could, he dashed through the diminishing wall of flame and made a beeline for the starboard side, as far as he could get in the least amount of time.

After taking a quick look around the horizon to see if any more Bettys were coming at him, Lieutenant Westin, the after 1.1-inch battery commander, grabbed a sailor manning a damage-control telephone and, together, they ran out the fire hose located beneath Turret-3, the after triple-8-inch turret. As soon as the hose was deployed, Westin signaled another sailor to turn on the water, but there was not enough pressure to reach the burning 20mm gun platform, which was about 20 feet over Westin’s head. Westin immediately signaled for the water to be turned off, then led the hose up the ladder that climbed the face of Turret-3. The added height did the trick, and the fire on the gun platform was quenched less than a minute after the water was turned on again. Other quick-thinking hose handlers doused all the fires within minutes of impact, though rescuers such as Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Reinhardt Keppler moved right through the flames to pull shipmates from the conflagration.

Fifteen men were killed outright by the impact of the Betty or its flaming fuel. Twenty-nine who were dragged from the inferno suffered a wide range of injuries.

Radioman 3rd Class Robert Coates, who left his station in Radio-2, an unscathed compartment directly beneath the incinerated 20mm gun platform, pulled one grievously burned victim from the smoldering ruins. While awaiting corpsmen and a litter, the terribly burned and somewhat delirious sailor alternately called for his mother and begged Coates to “put me out of my misery.”

Commander Mark Crouter, the San Francisco’s executive officer, emerged from Battle-2 with extensive burns. On reporting to the midships dressing station, however, Crouter refused preferential treatment. In fact, he perched himself on a mess bench and drove the young doctor on duty there to distraction by refusing any treatment whatsoever until everyone else, even men with far milder injuries, had been treated. The doctor did not put up an argument he knew he was destined to lose, but he did detail a corpsman to wrap a blanket around the senior officer’s shoulders and give him a sedative to help ease the pain until the other casualties had been treated. Later, when all the injured were transferred to the transport President Jackson for treatment and evacuation to Noumea, Commander Crouter refused to leave his ship.

After fully recovering from the shock of nearly burning to death in a shower of aviation gasoline, Seaman 1st Class Willie Boyce ventured down to the crew’s messing compartment to visit with a buddy who had come a lot closer. After chiding the burned man for going on duty near the crash site dressed only in a skivvy shirt and dungarees, Boyce asked if there was anything the burned man needed. “Willie,” the shipmate explained, “after the plane crash and during the scuffle I lost my crucifix. I want one. Would you find me another?” Boyce ran topside and asked another Catholic member of the aviation division if he would be willing to give up his crucifix for the burned man. The sailor complied without a word, and Boyce returned to the mess compartment to deliver the article. After placing the crucifix on the burned man’s incongruously unburned chest, Boyce again returned topside. Days later, he heard that his severely injured buddy was among seven San Francisco sailors who succumbed to their injuries aboard the President Jackson.

At 3:30, long after it was determined that there were no more Japanese aircraft in the area or on the way, the American transports and cargo ships returned to their anchorages off Kukum and Lunga Point. The few daylight hours remaining in the day were filled with furious activity, for the word was that all the transports and cargo ships would be sailing that evening to the rear base at Espiritu Santo. News from aerial scouts and coastwatchers operating far up the Solomons chain confirmed rumors that a powerful—perhaps overwhelming—Japanese naval surface battle group was on the way to Guadalcanal.

That night, after the transports and several escort vessels were safely clear of the Guadalcanal area, five U.S. Navy cruisers and eight destroyers under the command of Rear Adm. Daniel Callaghan and Rear Adm. Norman Scott fought the pivotal naval surface battle of the campaign. Both American admirals were killed and six of the U.S. Navy warships were sunk, but the desperate Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was a clear American victory that decisively turned the tide in the Pacific.

Eric Hammel is a professional military historian and author of nearly 30 books, including four on the Guadalcanal Campaign. This article is an edited excerpt from his Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, Pacifica Military History, 1988.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments