By Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

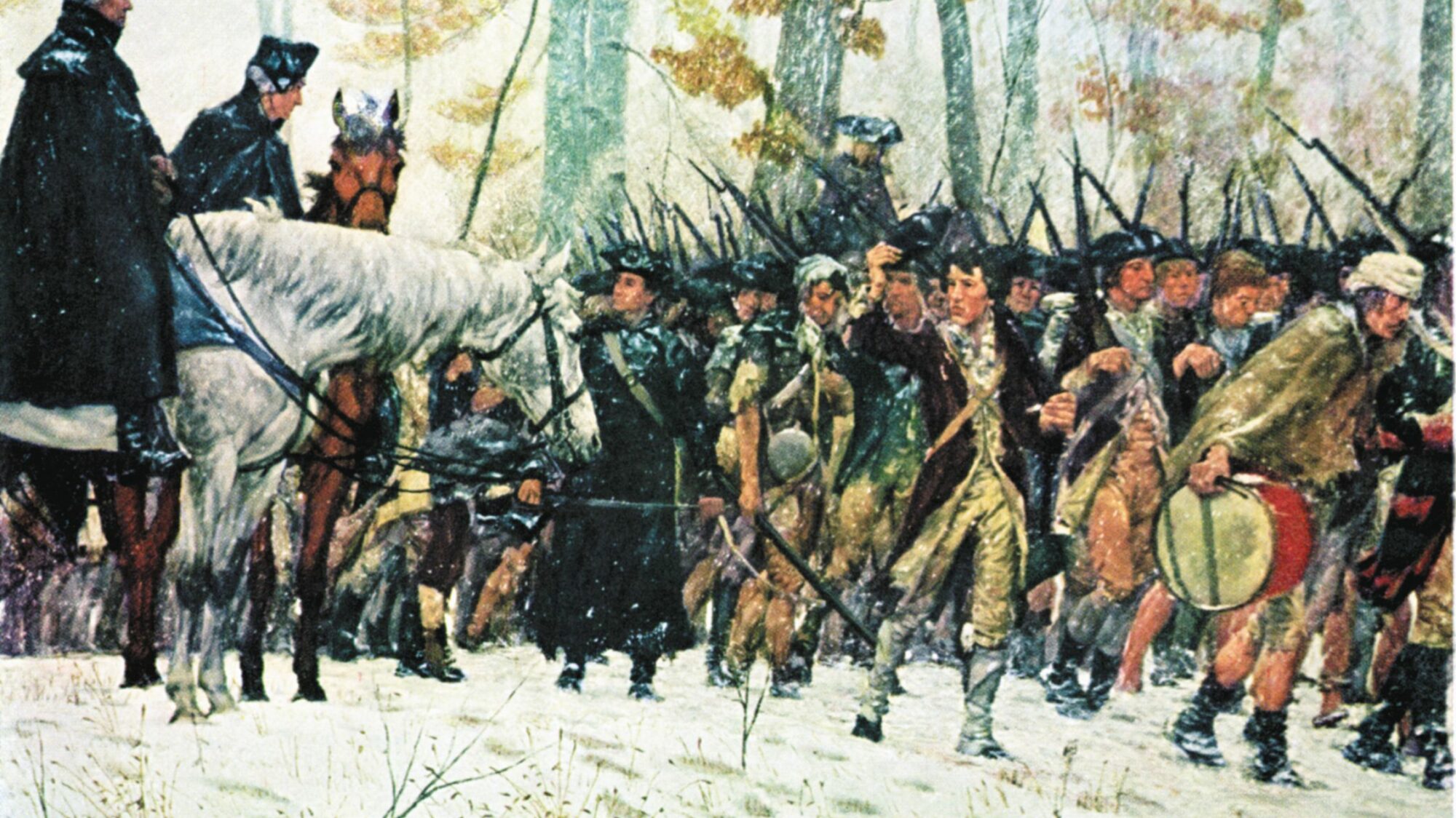

The freezing winter of 1777-1778, which General George Washington’s Continental Army spent on the verge of starvation and collapse at Valley Forge, was a turning point of the American Revolution. The Continental Army emerged from this ordeal a better trained, disciplined, and more cohesive force capable of engaging and defeating the British Army in the field.

During this apparent lull in the fighting, Washington was engaged in a more deadly form of combat that could have resulted in his dismissal as commander-in-chief and the demise of the Continental Army. Washington’s “secret war”—against misguided political zealots, ideological detractors, and jealous competitors—is the subject of Thomas Fleming’s superb popular history Washington’s Secret War: The Hidden History of Valley Forge (Smithsonian Books/Collins, New York, 2005, 384 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover).

During this apparent lull in the fighting, Washington was engaged in a more deadly form of combat that could have resulted in his dismissal as commander-in-chief and the demise of the Continental Army. Washington’s “secret war”—against misguided political zealots, ideological detractors, and jealous competitors—is the subject of Thomas Fleming’s superb popular history Washington’s Secret War: The Hidden History of Valley Forge (Smithsonian Books/Collins, New York, 2005, 384 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover).

The Continental Army that trudged into Valley Forge in December 1777 was demoralized by recent defeats at Brandywine (September 11, 1777), Paoli (September 21), and Germantown (October 4). Moreover, after the rout at Paoli, the Continental Congress fled Philadelphia—America’s largest and most prosperous city and the third largest in the British Empire—which was occupied by the British on September 26.

Disillusionment and defeatism were rife in this environment, and doubts were being expressed about Washington’s generalship and his ability to continue to lead the army. One of Washington’s most outspoken critics was Irish-born Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway. For three months, from September to December 1777, the “Conway Cabal” tried to stir congressional dissatisfaction with the war effort and have Washington replaced by General Horatio Gates. Conway failed and resigned shortly thereafter.

Other factors contributed to Washington’s and his army’s difficulties. The Continental Congress tried to micro-manage the army’s supply system, convinced that no one should make money out of the war, which resulted in shoddy or inadequate equipment. Washington’s soldiers were unable to interdict British foraging parties.

Washington, generally not considered a political figure while in uniform, proved himself a skillful and resolute politician against many domestic foes. One was Samuel Adams, leader of the Massachusetts delegation; another was the “true whig extremist” Dr. Benjamin Rush, who slandered Washington in unsigned letters to other politicians. With the aid of loyal politicians, Washington adroitly outmaneuvered his adversaries. At the same time, assisted by devoted military leaders (such as the Marquis de Lafayette and General Friedrich von Steuben), the charismatic and conscientious Washington molded the Continental Army into a relatively effective fighting force.

While Washington’s political machinations have been neither “secret” nor “hidden,” this compelling narrative sheds new light on the complex character of the American icon General George Washington.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

The Last Duel: A True Story of Crime, Scandal, and Trial by Combat in Medieval France, by Eric Jager, Broadway Books, New York, 2004, 242 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, list of sources, index, $24.95, hardcover.

On a cold December morning in 1386, eager crowds thronged a large field near a Paris monastery. A determined, fully armored knight sat at each end of the rectangular enclosure, ready to fight his opponent to the death. This is the true saga, as told compellingly by Dr. Eric Jager, of French knight Jean de Carrouges, his wife Marguerite, and squire (later knight) Jacques le Gris. When Carrouges returned home to France from campaigning in Scotland, his wife accused Le Gris, her husband’s old friend and rival, of savagely raping her. Carrouges took his complaint and sought justice directly from the king. The deadlocked court decreed a “trial by combat” to settle the case.

In medieval times, the outcome of the judicial duel was certain death for one party, a result believed to be in accordance with God’s will. If Carrouges won the trial by combat, his and his wife’s honor would be avenged. If Carrouges lost, he would not only forfeit his own life and property, but his wife would be burned at the stake since the result of the judicial duel had seemingly proved that she had committed perjury. The chivalric dance of death between Carrouges and Le Gris began with resolute jousts and eventually included excruciating battle on foot with swords, axes, and finally daggers. The suspenseful and lively action, described blow-by-bloody blow, resulted in victory for…. Read this fascinating account of the last legally ordered judicial combat in Paris and find out for yourself!

In Brief

The Greatest War Stories Never Told, by Rick Beyer, Collins, New York, 2005, 214 pp., illustrations, sources, $18.95, small format hardcover.

“War can be a catalyst for change, an engine for innovation,” observes History Channel documentary producer and writer Rick Beyer, “and an arena for valor, deceit, intrigue, ambition, audacity, folly, and yes, humor.” Many of these elements are contained in the 100 two-page and well-illustrated vignettes from military history that Beyer has included in this volume. These “tales” begin in 371 BC with the “Sacred Band,” a unique Theban military unit consisting of 150 homosexual couples who would fight to the death both to protect their lovers and to avoid shaming themselves in front of their lovers. Others include the introduction of cannon into Europe in 1287; the inspirational and “amazing” story of Joan of Arc leading the French to victory at Orleans in 1428; the “defenestration of Prague” in 1618 that began the murderous Thirty Years’ War; and the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Almost 20 stories pertain to World War II episodes, and the last anecdote alludes to predicting the start of the Gulf War in 1991 based on the surge of late-night pizza deliveries at the Pentagon. Many of these short stories do “astonish, bewilder, and stupefy,” but it is definitely an exaggeration to state that these are war stories that have never been told before. Nonetheless, this slim volume is an enjoyable and interesting “read.”

San Francisco’s Presidio, by Robert W. Bowen, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2005, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, $19.95, softcover.

San Francisco’s Presidio, by Robert W. Bowen, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2005, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, $19.95, softcover.

The Presidio (fort) of San Francisco in northern California was established by the Spanish in 1776 to protect their newly claimed territory and the immense anchorage of San Francisco Bay. The United States formally occupied the abandoned Presidio in 1847 during the U.S. Mexican War. From that time to the present, the history of the Presidio of San Francisco is told pictorially and in a chronological manner. The approximately 200 illustrations and photographs included in this volume are interesting, thought-provoking, and poignant. They depict not only the history of this storied military installation, but also the evolution of the U.S. Army and its uniforms, training, weapons, architecture, and culture. The Presidio of San Francisco was one of many military installations closed in 1994, and this fine pictorial history does an outstanding job of preserving and perpetuating the military history and heritage of this memorable military post and the stalwart soldiers who served there.

Blue Water Creek and the First Sioux War, 1854-1856, by R. Eli Paul, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2004, 256 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Blue Water Creek and the First Sioux War, 1854-1856, by R. Eli Paul, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2004, 256 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

The U.S. military campaigns against the Sioux Indians after the Civil War have overshadowed the seminal First Sioux War of 1854-1856. R. Eli Paul reconstructs in absorbing detail, using the first-hand accounts of military and Indian participants, Army reports, and various government documents, this clash between conflicting cultures and westward expansion. A small Army detachment, led by Lt. John L. Grattan, was sent to a Miniconjou Sioux village near Fort Laramie, Wyoming, on August 19, 1854, to apprehend an Indian who had allegedly stolen an emigrant’s cow. In the ensuing confrontation, Grattan and his men were wiped out, and the First Sioux War was ignited. The following year, Brevet Brig. Gen. William S. Harney led a 600-man punitive expedition that attacked a Sioux village on the Blue Water Creek, a tributary of the North Platte River, on September 3, 1855. Most of the 86 Indians killed were shot fleeing the area; less than a dozen soldiers were casualties. This was the major action of the First Sioux War, as chronicled vividly by Paul, which ended with the Fort Pierre treaty council of 1856.

Confederate Courage on Other Fields: Four Lesser Known Accounts of the War Between the States, by Mark J. Crawford, McFarland Publishers, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 189 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, references, index, $29.95, softcover.

Confederate Courage on Other Fields: Four Lesser Known Accounts of the War Between the States, by Mark J. Crawford, McFarland Publishers, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 189 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, references, index, $29.95, softcover.

The large-scale and prominent battles of Shiloh, Antietam, Vicksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and Atlanta, among others, have overshadowed many smaller and little known episodes of the Civil War. In this book, Mark J. Crawford has written four accounts of Confederate combat and valor on lesser known fields. The first chronicles the long march and dramatic Confederate charge across a rain-swollen stream at Dinwiddie Courthouse (March 31, 1865), where many of the attackers were swept away and drowned. The second section is woven around the letters of Colonel Charles Blacknall, 23rd North Carolina Infantry, who yearned for combat. Blacknall was wounded in the foot in 1864, refused amputation, and died shortly thereafter. A series of conflicts and acts of retaliation in southeastern Missouri, frequently including civilians, is chronicled in the third section. The fourth vignette is an account of the history and operations of Confederate General Hospital One, located at the former exclusive resort at Kittrell’s Springs, North Carolina, from 1864-1865. This account is based largely on the observations of the hospital chief surgeon and the chaplain. These interesting narratives, containing much information from soldiers’ accounts, help put a human face on the frequently anonymous aspects of war and suffering.

Lt. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir, by Charles B. Gatewood, edited by Louis Kraft, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Lt. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir, by Charles B. Gatewood, edited by Louis Kraft, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

U.S. Army Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood graduated from West Point in 1877 and reported for duty at Camp (later Fort) Apache, Arizona, in 1878. From March 1879 to June 1880, and again from November 1881 until October 1885, Gatewood was in charge of Indian scouts. This coincided with periodic outbreaks of violence, led by Victorio and later by Geronimo. Gatewood led numerous patrols, and by 1882, he “had ridden the war trail with native scouts constantly since his arrival in the Southwest.” He became known as one of the Army’s premier “Apache” men. These hardships, however, had a negative impact on Gatewood’s health. His empathy with the Indians made him realize that “white men cheated their Indian wards” and set him on a collision course with his superiors and the Army. Gatewood’s significant role in Geronimo’s 1886 surrender was downplayed. He was denied promotion to captain, and he died in 1896. Based on Gatewood’s unpublished memoir, this book reveals many of the good, and not so good, elements of the frontier army and its last campaigns against the Indians.

Franco: Soldier, Commander, Dictator, by Geoffrey Jensen, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 135 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographic note, index, $19.95, hardcover.

Franco: Soldier, Commander, Dictator, by Geoffrey Jensen, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 135 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographic note, index, $19.95, hardcover.

Generalissimo Francisco Franco is best known as the brutal leader of the victorious Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, and as the ruthless dictator of Spain from 1939 until his death in 1975. In this fine biographical account, historian Geoffrey Jensen divides the life of El Caudillo (the “supreme leader”) into six parts. The first chapter chronicles Franco’s life from birth in 1892 until his graduation from the Infantry Academy in 1910. In 1912, as described in Chapter 2, Franco was posted to Morocco where he participated in counterinsurgency operations against Berber tribes. Chapter 3, “The Rising Star,” and Chapter 4, “From Reluctant Rebel to Generalisimo,” cover Franco’s service from 1920 to 1936. The Spanish Civil War, the “dress rehearsal” for World War II in which Franco played a leading role and allied himself with Hitler and Mussolini against the “godless Marxists,” is the topic of Chapter 5. A concluding chapter traces Franco’s life and dictatorship until his death in 1975. This well-crafted book provides an insightful starting point for additional study of Franco’s life, leadership, and times.

Hospital at War: The 95th Evacuation Hospital in World War II, by Zachary B. Friedenberg, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2004, 158 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, index, $32.50, hardcover.

Hospital at War: The 95th Evacuation Hospital in World War II, by Zachary B. Friedenberg, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2004, 158 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, index, $32.50, hardcover.

The 95th Evacuation Hospital was one, and probably representative, of the 107 U.S. Army evacuation hospitals active during World War II. This interesting and perceptive volume, written by a former wartime unit surgeon, is a collective history of the 95th, highlighting its operations, activities in treating combat casualties, and personnel. Elements of the unit assembled at Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky, in early 1943, and the 95th deployed to North Africa in April 1943. The unit landed at Salerno on D-day in September 1943, and served in Italy (including Monte Cassino and Anzio), before landing in southern France in August 1944. The hospital followed the action to the north of France, participated in the Battle of the Bulge, and crossed the Rhine into Germany in March 1945. Motivated by a sense of duty, service, and urgency, the 95th admitted 41,663 wounded combat troops in almost two years of overseas operations. Friedenberg wrote this book to “pay homage to the spirit, energy, and heroism of the members of the 95th Evacuation Hospital and the thousands of wounded soldiers it treated.” On all counts, the mission was accomplished.

Brassey’s D-Day Encyclopedia: The Normandy Invasion, A-Z, by Barrett Tillman, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 302 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover.

Brassey’s D-Day Encyclopedia: The Normandy Invasion, A-Z, by Barrett Tillman, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 302 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover.

This worthwhile volume is an A-to-Z encyclopedia of entries on military, naval, airpower, and cultural topics related to the Normandy invasion of June 6, 1944. Many key, senior, and prominent military leaders of the various Allied and German military services are included. Entries on “Aircraft” and “Weapons,” for example, enumerate with specific information the diverse aircraft and weapons used on D-day. Topics related to popular culture include “music, motion pictures, museums, even D-day quotations.” Apparently for continuity purposes, a number of post D-day military activities in Normandy (such as the capture of Cherbourg) are included. It is annoying, however, that division, brigade, regimental, and battalion numerical designations are spelled out and not given properly as Arabic numerals (e.g., 1st). While Chandler and Collins’s 1994 D-day encyclopedia remains authoritative, Brassey’s D-Day Encyclopedia will be of use and value to American military readers and enthusiasts.

D-Day As They Saw It, edited by Jon E. Lewis, Carroll & Graf, New York, 2004, 336 pp., illustrations, map, appendices, $14.00, softcover.

D-Day As They Saw It, edited by Jon E. Lewis, Carroll & Graf, New York, 2004, 336 pp., illustrations, map, appendices, $14.00, softcover.

The amphibious assault at Normandy on D-day, 1944, was truly watershed battle that has become representative of World War II. This enthralling volume contains first-hand accounts of participants in the preparatory events, the actual amphibious landings and operations on D-day, and the subsequent fighting in France during the summer of 1944. Accounts of prominent military leaders, such as U.S. General Omar N. Bradley and German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, are compiled in this collection, as are the combat reports from experienced war correspondents, including Ernie Pyle, Ernest Hemingway, and Alan Melville. Other soldiers, sailors, and airmen, American, British, Canadian, and German, provide emotion-filled eyewitness accounts that candidly depict the hopes and fears, courage and sacrifices, and trials and tribulations of combat in Normandy. These interesting accounts also serve as a lasting tribute to those who stared death in the face on that “longest day,” June 6, 1944, and the subsequent ferocious military operations in Normandy.

The Gothic Line: Canada’s Month of Hell in World War II Italy, by Mark Zuehlke, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, 2005, 551 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Gothic Line: Canada’s Month of Hell in World War II Italy, by Mark Zuehlke, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, 2005, 551 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The slugfest in the mountains and mire of Italy made this campaign one of the most hard-fought, yet underappreciated, operations of World War II. This was especially true in the fall of 1944, when the Canadian Corps (Canadian 1st Infantry and 5th Armored Divisions) was tasked to spearhead the Eighth Army’s breakthrough of the heavily defended German Gothic Line. In this operation, dubbed Operation Olive, the Canadian Corps attacked northward on the Adriatic road on August 25, 1944. The important role of the Canadian Corps in breaking the Gothic Line is vividly told through the eyes and accounts of participating Canadian soldiers.

The Pacific War Companion: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima, edited by Daniel Marston, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2005, 272 pp., illustrations, maps, endnotes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Pacific War Companion: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima, edited by Daniel Marston, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2005, 272 pp., illustrations, maps, endnotes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

This interesting collection of essays, all written by prominent military historians, was published to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Pacific. Edited by Dr. Daniel Marston of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, the 13 chapters in this fine volume provide American, British, and Japanese perspectives on various topics and issues of the Pacific War. These chapters include Dennis Showalter’s “Storm Over the Pacific: Japan’s Road to Empire and War,” Ken Kotani’s “Pearl Harbor: Japanese Planning and Command Structure,” and “Coping with Disaster: Allied Strategy and Command in the Pacific,” by Raymond Callahan. Early Pacific naval and land operations are examined by Robert Love in “The Height of Folly: The Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway,” and in Marston’s “Learning from Defeat: The Burma Campaign.” The experiences of men in battle are conveyed well in Joseph H. Alexander’s “Across the Reef: Amphibious Warfare in the Pacific,” and “The Island Experience—The Battle for Okinawa: April 1-June 21, 1945,” by Bruce Gudmundsson. The last essay in this handsomely produced, profusely illustrated, and uniformly excellent volume is Richard B. Frank’s “Ending the Pacific War: ‘No Alternative to Annihilation.’” His grim and arguably realistic conclusion about the use of atomic bombs is that they “were awful, but the alternatives were much worse.”

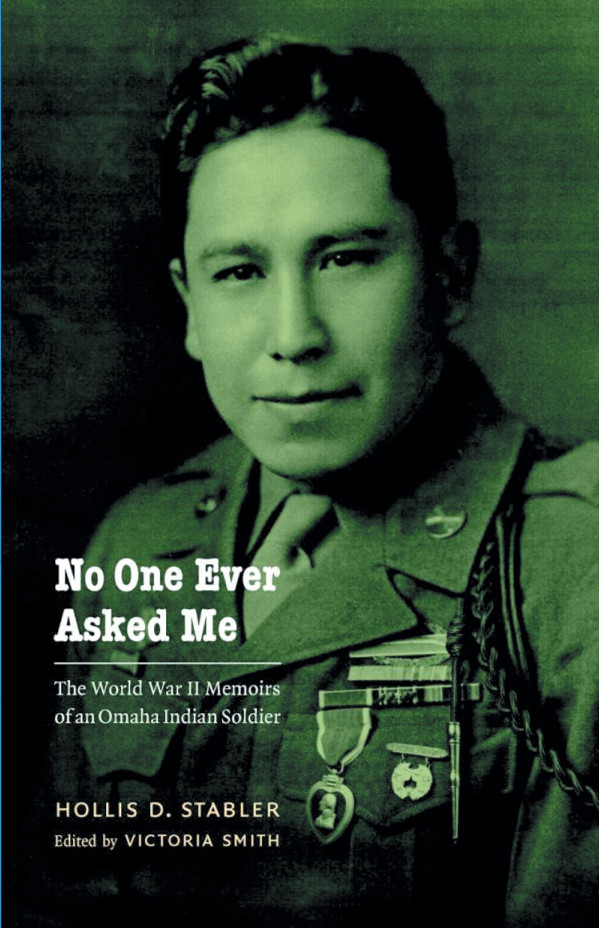

No One Ever Asked Me: The World War II Memoirs of an Omaha Indian Soldier, by Hollis D. Stabler, edited by Victoria Smith, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 182 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, index, $24.95, hardcover.

No One Ever Asked Me: The World War II Memoirs of an Omaha Indian Soldier, by Hollis D. Stabler, edited by Victoria Smith, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 182 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, index, $24.95, hardcover.

“I’m not a hero, you know,” proclaimed Hollis D. Stabler, “I was just a guy in the army, part of a team.” In 1939, before American entry into World War II, 21-year-old Omaha Indian Stabler enlisted in the Army and served largely in combat through the war. He was one of about 25,000 American Indians, out of a total U.S. Indian population of about 350,0000 in 1940, to serve in the armed forces during World War II. Initially serving in the prewar 11th Cavalry Regiment, this unit was converted to an armored cavalry regiment early in the war. Stabler fought in North Africa and Sicily before volunteering to serve with the Rangers, and saw further combat at Anzio and Cisterna. As a member of the 1st Special Service Force, Stabler participated in Operation Anvil. As his brother was killed earlier in the war, Stabler was reassigned to noncombat duty. This collaborative biography, containing extracts from Stabler’s oral interviews and written recollections, is woven together by the editor’s narrative (which contains too many avoidable historical errors). Providing a glimpse into the experiences of a World War II Indian warrior, Stabler’s interesting memoir serves as a reminder that war “is unrelenting hunger and thirst, fatigue, grime, noise, pain, anger, stench, fear, courage, death, homesickness, loneliness, vulnerability, valor, heartache … ingrown toenails.”

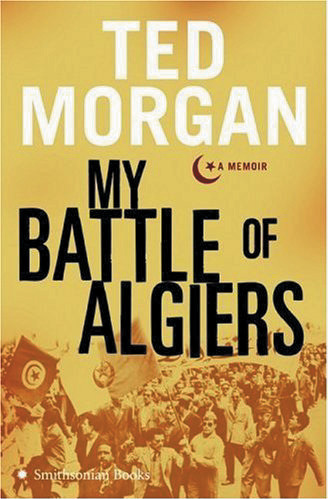

My Battle of Algiers: A Memoir, by Ted Morgan, Smithsonian Books/Collins, New York, 2006, 304 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $24.95, hardcover.

My Battle of Algiers: A Memoir, by Ted Morgan, Smithsonian Books/Collins, New York, 2006, 304 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Noted biographer and historian Ted Morgan was born in France as the aristocrat Sanche de Gramont in 1932. Even though he graduated from Yale University, Morgan remained a French citizen and was drafted into the French Army in 1955. Morgan chronicles in fascinating, thought-provoking, and occasionally ribald detail his French Army training, resulting in his commissioning as a second lieutenant in August 1956. This was during the build-up of French forces in Algeria to fight the growing “insurgent” independence movement. Morgan initially served in the 1st Regiment of the Colonial Infantry, in the countryside south of Algiers. His experiences were harrowing and he admits pummeling to death an Arab during an “interrogation.” A few months later, largely due to family connections and prior journalism experience, Morgan was reassigned to write French propaganda in Algiers. He observed and participated in the fierce but effective urban terrorism in Algiers, and in this book explains the French tactics. This riveting and timely book can serve as a prelude to the current morass in Iraq, where the results will echo those of the French in Algeria.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments