By Michael D. Hull

Outside the Ministry of Defense in London is a statue of one of the most influential yet overlooked leaders of World War II—an officer considered by many to have done more than any other to defeat Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

The statue of Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, Chief of the British Imperial General Staff from December 1941 until 1945, is inscribed, “Master of Strategy.”

Born into a well-to-do Ulster family transplanted to the town of Pau in southern France, a decorated World War I Royal Artillery veteran, and commander of the 2nd Corps at Dunkirk, Alan Francis Brooke was resolute, logical, articulate, and probably the best British strategist since the Duke of Marlborough. He had an unerring grasp of both detail and the broader view, and became the acknowledged conscience of the British Army.

But Alanbrooke does not feature in the mythology of World War II because he did not capture headlines by winning famous battles. Prime Minister Winston Churchill preferred him in charge of those who did, and Alanbrooke, like his American counterpart General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff, put duty before martial ambition. Both were promised command of the Allied invasion of Normandy, but both were ultimately considered indispensable by their superiors, Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But Alanbrooke does not feature in the mythology of World War II because he did not capture headlines by winning famous battles. Prime Minister Winston Churchill preferred him in charge of those who did, and Alanbrooke, like his American counterpart General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff, put duty before martial ambition. Both were promised command of the Allied invasion of Normandy, but both were ultimately considered indispensable by their superiors, Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Alanbrooke himself had turned down “the finest command I could ever hope for”—the Middle East Command—in August 1942, because he believed “it would take at least six months for any successor, taking over from me (as commander of the Imperial General Staff), to become as familiar with Churchill and his ways…. Winston never realized what this decision cost me.”

As detailed in Alanbrooke’s War Diaries 1939-1945 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles; 2001; hardcover; 763pp.; 16 photographs, notes, index; $40.00), the field marshal’s relationship with the prime minister was a close and stormy one, marked by mutual admiration, frequent confrontations, rage, and frustration. In Alanbrooke, the intuitive, impulsive, interfering Churchill had found his perfect foil. Alanbrooke was one of the few with the intellect and temperament to face him down.

Churchill ranted and railed, but never overruled him. As the prime minister reported, “I thump the table and push my face towards him, and what does he do? Thumps the table harder and glares back at me.” While acknowledging that the prime minister “is quite the most wonderful man I have ever met,” Alanbrooke confides in his diary, “He knows no details, has only got half the picture in his mind, talks absurdities, and makes my blood boil to listen to his nonsense…. Without him, England was lost for certainty; with him, England has been on the verge of disaster time and time again.”

The field marshal, whose diaries are replete with caustic observations that he kept to himself and reveal a total inability to suffer fools gladly, concludes that his superior was both a man who stood “head and shoulders above all others” and “a public menace.”

One of the most important World War II books to appear in several years, Alanbrooke’s diaries—penned nightly and against regulations—provide a riveting, high-level, day-by-day record of how the war was won that will enthrall any military scholar. His every moment of triumph, exhilaration, depression, and doubt is recorded, and his rapier judgments spare no one—politicians, Americans, Russians, French, Chinese, and his own generals.

Dark, immaculate, efficient, and crisply British, Alanbrooke was disliked by most Americans, and vice versa. A notable exception was General Douglas A. MacArthur; their adulation was mutual. However, his affection for Marshall and General Dwight D. Eisenhower was not matched by professional respect.

Of Marshall, he says, “There was a great charm and dignity about Marshall which could not fail to appeal to one. A big man and a very great gentleman, who inspired trust, but did not impress me by the ability of his brain.”

And of Ike, he writes, “I am afraid that Eisenhower as a general is hopeless! He submerges himself in politics (as during the 1942 North African invasion) and neglects his military duties, partly, I am afraid, because he knows little if anything about military matters…. As supreme commander, what he may have lacked in military ability he greatly made up for by the charm of his personality.”

As for his protégé, Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, these diaries indicate that Alanbrooke exercised unwavering loyalty and patience when the prickly, uncompromising Monty was under assault from both his American and British associates in 1944-1945: “He requires a lot of educating to make him see the whole situation, and the war as a whole outside Eighth Army orbit. A difficult mixture to handle.”

And the diaries crackle with Alanbrooke’s impressions of the other leaders and generals with whom he worked.

Roosevelt: “Never made any great pretense at being a strategist”; Marshal Josef Stalin: “He has got an unpleasantly cold, crafty, dead face” … but “he had a military brain of the very highest caliber”; Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek: “A shrewd but small man … he was certainly very successful in leading the Americans down the garden path”; General Charles de Gaulle: “Whatever good qualities he may have had were marred by his overbearing manner, his ‘megalomania’ and his lack of cooperative spirit”; Lord Louis Mountbatten: “His half-baked thoughts thrown into the discussion certainly don’t assist … he is the most crashing bore”; Lord Beaverbrook, minister of production: “An evil genius who exercises the very worst of influence on Winston”; Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander: “He must have someone else to lean on!”; General George S. Patton Jr.: “A dashing, courageous, wild and unbalanced leader … but at a loss in any operation requiring skill and judgment”; General Joseph W. Stilwell: “A stout-hearted fighter” … but had little military knowledge and no strategic ability of any kind”; General Claire L. Chennault: “A very gallant airman with a limited brain.”

Candid, provocative, and revealing, the Alanbrooke diaries constitute a unique personal chronicle of the war.

Recent And Recommended

Recent And Recommended

Carlson’s Raid by George W. Smith; Presidio Press, Novato, Calif.; 2001; hardcover; 262pp.; 32 photographs, 2 maps, index; $29.95.

Meeting with Congressional leaders and his military chiefs of staff in the dark early weeks of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt kept asking how the Pacific Fleet could have been caught off guard at Pearl Harbor.

He became obsessed with launching some reprisal attacks against the Japanese—both to deliver a blow to their national pride and to raise American spirits. As reporter Quentin Reynolds observed, the president burned with “a fierce, consuming hatred for the Japanese.”

Two reprisals were hastily planned and effected.

The first was the April 18, 1942, raid on Japan by 16 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers led by Lt. Col. James Doolittle. Flying from the carrier USS Hornet, the bombers inflicted minimal damage on Japanese targets, but the daring raid provided a great lift to American morale.

The second bold initiative, which FDR personally fought for against the objections of Marine Corps generals, was the establishment of Marine raider battalions based on the concept of the British Army Commandos, about whose exploits the president had received glowing reports.

The first such raid—a diversion to the invasion of Guadalcanal by the lst Marine Division—occurred on August 17-18, 1942, when 219 men of Lt. Col. Evans Fordyce Carlson’s 2nd Marine Raider Battalion attacked the small Japanese outpost at Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands. Crammed into two big submarines, the USS Nautilus and USS Argonaut, two stripped-down companies—with Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son, as executive officer—traveled 2,000 miles from Pearl Harbor and waded ashore on Makin on August 17. “Carlson’s Raiders” captured the atoll in two days of fierce fighting, destroyed a radio station, burned enemy equipment, and seized valuable documents.

The operation was hailed as a great victory, and the Raiders were lionized by the American press and public hungry for good news from the Pacific. But, says author Smith in this definitive, balanced, and readable history, the raid’s long-term consequences were less than fortunate. Stirred up by the attack, the Japanese were able to flush out Australian coastwatchers who had been providing valuable intelligence, and they began to fortify the Gilberts.

When the 2nd Marine Division assaulted Tarawa Atoll in November 1943, the Japanese were ready.

A Hartford, Conn., journalist and Vietnam War veteran, Smith has done a thorough job of chronicling the raid—its hasty planning, its hour-by-hour action, and its aftermath—and of portraying its leader, the gaunt, Lincolnesque maverick Marine who had marched with the Communist Chinese Eighth Route Army in the 1930s and adapted its concept of “gung-ho” (work together) for his Raider battalion.

The author shows how the Makin raid was fully exploited by the Navy and Marine Corps public relations machinery. Medals were awarded all around, recruiting received a big boost, and the motto of Carlson’s battalion entered the American lexicon. The following year, Hollywood jumped into the action with the release of Walter Wanger’s Gung Ho!, starring Randolph Scott. It was a box office hit and sold millions of dollars’ worth of war bonds.

Although Carlson was criticized by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz for not acting aggressively enough, for overestimating the enemy strength, and for overreliance on intelligence provided by natives, the Pacific Fleet commander was satisfied that the raid accomplished its primary mission. But, as Smith explains, there was much criticism that the Makin Island raid was a waste of manpower and resources that could have been better used elsewhere. Marine General Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith sniffed, “Carlson’s raid was a spectacular performance, but it was also a piece of folly. The raid had no useful purpose and served only to alert the Japanese to our intentions in the Gilberts.”

The author examines carefully the questions that remained about the loss of 30 of Carlson’s men. There were contemporary rumors that Raiders were “left behind” by their comrades, but Private Brian Quirk insists in this book, “They were accidentally lost either on land or in the water. There is a clear distinction between being left behind or accidentally lost.”

In fact, says Smith, 19 of Carlson’s men were found in a mass grave on the island of Butaritari in December 1999, and positively identified a year later; two were believed missing, and nine were captured and later beheaded on Kwajalein.

The most disturbing chapter in this well-researched and objective study concerns Carlson’s reported—and long hushed-up—consideration of surrendering because of his concern for the wounded and the possible fate of the president’s son. Half of the force’s weapons had been lost in the surf, its ammunition was gone, and Carlson feared that the Japanese had landed reinforcements on the island. “I can see why this was an option for him, a course of action,” says Quirk. “Carlson was certainly not a coward. Believe me, he was one courageous guy.”

He later led the Marine Raiders’ famous 150-mile “long patrol” on Guadalcanal, served at Tarawa and Saipan, and collected three Navy Crosses.

Smith has negotiated deftly through contemporary propaganda, wartime ballyhoo, and many conflicting reports to create a factual and gripping history of the Makin Island raid. It is as reliable as any we are likely to see.

Montgomery and “Colossal Cracks” by Stephen Ashley Hart, Praeger Publishers, Westport, Conn.; 2001; hardcover; 214pp.; photographs, maps, index; $59.95.

Montgomery and “Colossal Cracks” by Stephen Ashley Hart, Praeger Publishers, Westport, Conn.; 2001; hardcover; 214pp.; photographs, maps, index; $59.95.

A D-Day objective only nine miles from the English Channel coast, the historic French city of Caen on the Orne River saw the bitterest fighting of the 1944 Normandy campaign.

There, the British Second and Canadian First armies struggled to make headway against the bulk of the German armor in Normandy, and by the end of June both sides were locked in a bloody stalemate. Criticism mounted that General Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of the British 21st Army Group, had lost control of the campaign.

Yet the wiry, highly professional victor of El Alamein insisted that everything was “going according to plan.” By drawing the panzer divisions to his sector and mounting a series of offensive operations, notably Epsom (June 26-July 1) and Goodwood (July 18-21), Monty’s strategy was aimed at ensuring that the planned breakout in the West, Operation Cobra—by General Omar N. Bradley’s U.S. First Army—would meet minimal opposition.

This strategy, which Montgomery maintained had been his preinvasion plan, eventually worked. But the stigma of Caen—flattened to rubble and finally seized by General Henry D.G. Crerar’s Canadians in late July—would tarnish Monty’s reputation.

The master of the set-piece battle was widely accused of excessive caution by many—both British and American—who did not understand his tactics or the unique problems he faced in Normandy. And he was not aided by a fastidious and egocentric personality that antagonized his fellow officers.

Monty was certainly guilty of caution in more than one instance, of missing opportunities, and of failing to exploit his victories to the fullest. But, as Stephen Ashley Hart points out in this scholarly and penetrating analysis of Montgomery and the 21st Army Group in 1944-1945, the focus placed by most historians on his distasteful personality has clouded his operational abilities.

The author, who is the senior war studies’ lecturer at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, explains convincingly that Monty’s caution, fixation on preoperation buildups, and predilection for overwhelming firepower and air support—“colossal cracks,” as he called them—were fully justified. This strategy was crude and methodical, says Hart, but was an appropriate way of achieving objectives.

The aim was to obtain victory over Germany within a larger Allied effort, and with tolerable casualties.

Montgomery was saddled with a critical British manpower shortage after five years of war and the fact that many of his infantry units were inadequately trained. Ironically, considering its long and unmatched record, the British Army in 1944 “was not very good,” says Hart, and Monty “did not regard his troops as capable of any higher performance” than a set-piece battle style of fighting.

So, Montgomery sought correctly to nurture his limited resources through an adequate, sustained combat performance that would, as part of the Allied effort, slowly grind the enemy down. In this context, says the author, Monty’s attritional “colossal cracks” involving massive artillery barrages and bomber raids on enemy strongpoints utilized the strengths of the British Army, notably its superb gunnery.

Unlike his ranking American counterparts, Montgomery had experienced the wasteful slaughter of 1914-1918. He was no Douglas Haig and strove always to prevent heavy losses, sustain morale by avoiding defeats, and keep Britain’s last substantial field army intact. Unlike Bradley, he could not replace all the casualties his army suffered in the liberation of Europe.

Montgomery’s method was cumbersome and cautious, Hart points out, but it eventually paid off after two months of relentless, heartbreaking slogging around Caen by ensuring the success of Operation Cobra and enabling General George S. Patton, Jr.’s U.S. Third Army to break out for its freewheeling advance eastward. The author reminds us that Patton’s success was as much the product of the Caen struggle and the timely collapse of German logistics as it was of his bold generalship.

All in all, Hart concludes, the “colossal cracks” strategy was a winning method, if not a flawless one.

Incisive, eminently objective, and literate, this thoughtful study advances considerably our understanding of the war’s most controversial field commander and his Normandy campaign.

The Will to Win by Paul F. Braim; Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2001; hardcover; 421pp.; 34 photographs, 18 maps, notes, index; $42.50.

The Will to Win by Paul F. Braim; Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2001; hardcover; 421pp.; 34 photographs, 18 maps, notes, index; $42.50.

When General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff, visited Utah Beach, Normandy, in June 1944, he was told by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander, that there was one regimental commander there who merited an on-the-spot promotion.

Learning that the officer was Colonel James Alward Van Fleet, commander of the 8th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division, Marshall responded testily that he had scratched his name from the promotion lists for years because he had been known in the Old Army as a drunkard. But it turned out that Marshall had been confusing Van Fleet—almost a complete teetotaller—with an officer named Van Vliet.

Marshall did penance by promoting the burly, vigorous, clean-living Van Fleet immediately. He was made assistant commander of the 2nd Infantry Division, took over the 90th Infantry Division from Maj. Gen. Raymond S. McLain in October 1944, and succeeded Maj. Gen. John Milliken as commanding general of III Corps in March 1945. Along the way, Van Fleet collected numerous decorations, including the Distinguished Service Cross, three Distinguished Service Medals, three Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, three Purple Hearts, and the Combat Infantryman Badge of which, like General Matthew B. Ridgway, he was the proudest.

Born in New Jersey, raised in rural Florida poverty, and a 1915 graduate of the West Point “class the stars fell on,” Van Fleet was a soldier’s soldier who believed in rigorous field training and mental conditioning. “The will to win” was his motto.

Optimistic, charismatic, and unassuming, he was a gentle man of inner peace who treated both officers and enlisted men with dignity. In this incisive, revealing, and gracefully written study, history professor Paul Braim has done a masterful job of bringing Van Fleet, one of the outstanding combat leaders of World War II, out of the shadow of more flamboyant commanders. It is a four-star biography of the man whom President Harry S Truman went so far as to call “the greatest general we ever had.”

This is an inspiring story of gallantry and unswerving devotion—an American military success story.

After detailing Van Fleet’s aggressive front-line leadership in action at Utah Beach, Cherbourg, St. Lo, Brest, and Metz, the author examines with admirable detail and authority his brilliant 1948-1950 leadership of the support mission to Greece, where he developed the Greek Army into a fighting force able to defeat a strong Communist insurgency, and his effective tenure as commander of the battered Eighth Army in Korea from 1951-1953, during which the South Korean Army assumed a major role and he earned the undying respect of President Syngman Rhee, who said, “His name is cherished by the Korean people.”

James Van Fleet, the author concludes, was a “field soldier” in the best tradition of taking the hard road of duty. He was a consummate leader who cared for his men, never sought special considerations or was afflicted with a headquarters mentality, and did not choose to be part of an elite. He was professional, selfless and, as Marine Corps Colonel Bruce E. Meyers observed, “one of America’s true centurions.”

Author Braim, a professor emeritus at Embry Riddle University, has crafted an eloquent tribute and a compelling military biography.

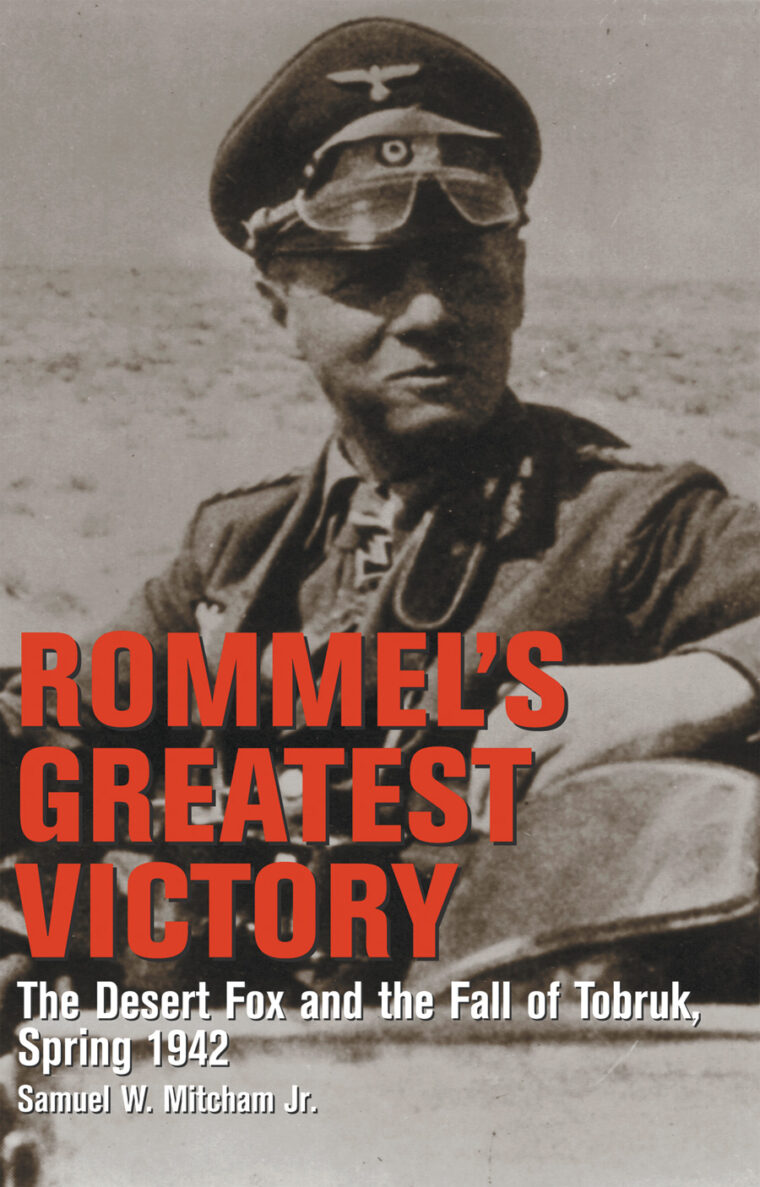

Rommel’s Greatest Victory by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr.; Presidio Press, Novato, Calif.; 2001; paper; 243pp.; 32 photographs, 18 maps, notes, index; $18.95.

Rommel’s Greatest Victory by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr.; Presidio Press, Novato, Calif.; 2001; paper; 243pp.; 32 photographs, 18 maps, notes, index; $18.95.

Tobruk, a town on the Libyan coast and one of the best harbors in the Mediterranean Sea, was a longtime thorn in the side of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, brilliant commander of the German Afrika Korps.

Captured from the Italians by General Archibald P. Wavell’s British forces in January 1941, the vital supply point was stubbornly held by British, Australian, South African, and Indian troops for a year and a half. Repeated German attacks were repelled, and Rommel was forced to bypass Tobruk.

Then, in late May 1942, the famed Desert Fox launched a new offensive against the port by outflanking the heavily mined Gazala Line with his panzers and attacking from the south. Unable to breach the defenses, Rommel withdrew, circled his tanks in a Western-style defense, and fended off furious British assaults before finally smashing the Gazala Line at Knightsbridge, a fortified box held by the Guards Brigade.

Rommel’s audacity left him free to concentrate all his weight on Tobruk. He besieged the port on June 18, 1942, and attacked two days later. Within three hours, he had broken through the defense lines and reached the harbor. On the following day, the garrison was forced to surrender.

The Germans took an estimated 33,000 prisoners and seized 2,000 vehicles, 5,000 tons of provisions, large quantities of ammunition, and 500,000 gallons of precious fuel.

It was, as Samuel Mitcham tells in this lucid and rapidly paced account, Rommel’s greatest victory and the worst British defeat of the protracted, seesaw war in the Western Desert. “The fall of Tobruk came as a staggering blow to the British cause,” said the British official history, while the South African official history stated, “The Afrika Korps was entitled to its hour of glory. The capture of Tobruk crowned what was probably the most spectacular series of victories ever gained over a British army.”

Promoted to field marshal by an ecstatic Adolf Hitler, the Desert Fox celebrated modestly with a can of pineapple and a small glass of well-watered whisky liberated from the British.

Closely following the Singapore disaster and the near loss of strategic Malta, the Tobruk defeat almost toppled Winston Churchill’s government. But he won a vote of confidence, the Eighth Army recovered after a 300-mile eastward retreat, and the Afrika Korps was forced onto the defensive at El Alamein four months later.

The author of several other highly readable books on Rommel and the Luftwaffe, Mitcham has crafted a scholarly and well-balanced history of one of World War II’s closest run and most pivotal battles.

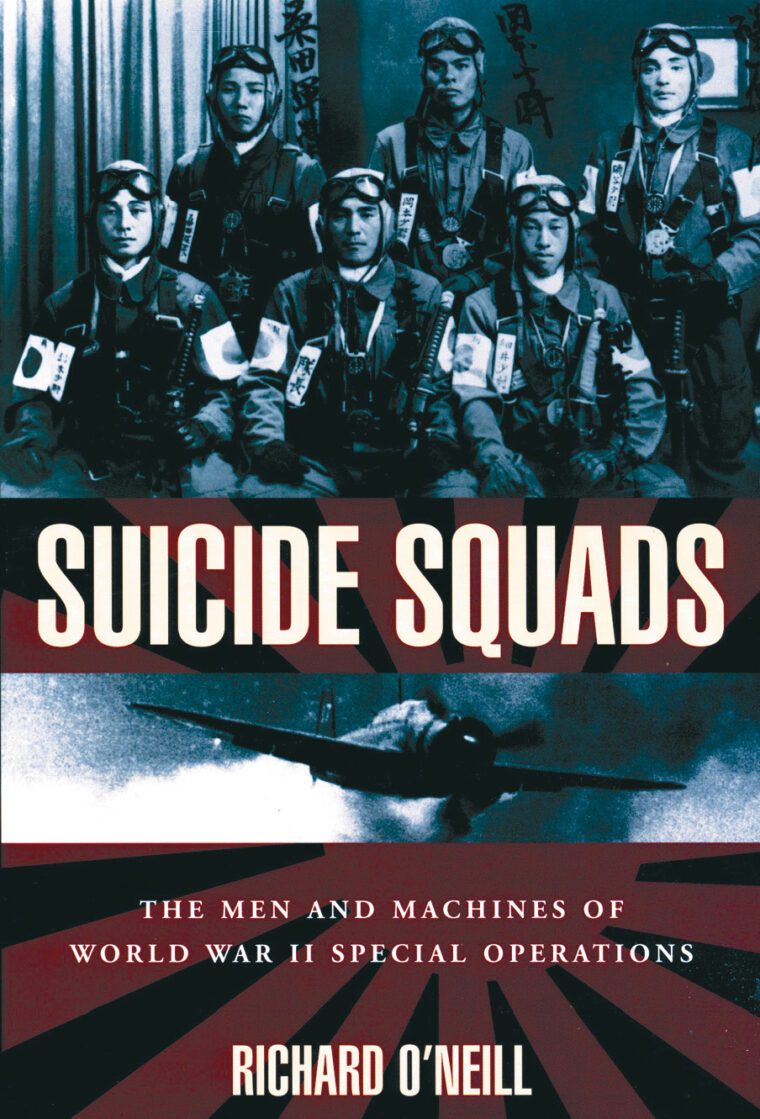

“Suicide Squads” by Richard O’Neill; The Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn.; 2001; paper; 272pp.; 19 photographs, glossary, index; $17.95.

“Suicide Squads” by Richard O’Neill; The Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn.; 2001; paper; 272pp.; 19 photographs, glossary, index; $17.95.

A daring six-man raid into the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt, on the night of December 18-19, 1941, caught the Royal Navy napping and upset the balance of naval power in the Mediterranean Sea.

Launched from a mother ship, the Scire, and led by Lieutenant Luigi Durand de la Penne, three Italian Maiale (“Pig”) manned torpedoes—each with a detachable warhead and a two-man crew—slipped through a gate in the harbor’s net-and-boom barrier and severely damaged the moored 30,000-ton British sister battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth, the tanker Sagona, and the destroyer HMS Jervis. Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, praised “the cold-blooded bravery and enterprise of these Italians,” and rated the damage “a disaster.”

Had the Italian naval general staff proved more resolute, and their German opposite numbers more supportive of their ally, the Pigs’ greatest success might significantly have affected the course of World War II. So says Richard O’Neill in this fascinating study of one of the war’s largely overlooked tactical aspects—the suicide or near-suicide missions carried out by Italian, German, British, and Japanese midget submarines, human torpedoes, explosive motorboats, piloted bombs, and kamikaze airplanes.

In a detailed, thoroughly researched, and crisply written exploration, the author explains the evolution, the types, and the effects of these weapons—from Pearl Harbor and Sydney Harbor to Sword Beach, Normandy, and Okinawa—and the resourcefulness and desperation that initiated such actions. The bravery of the sailors and airmen involved cannot be overestimated, he says.

Because their own country did not find it necessary to resort to such tactics, few Americans have been aware of World War II’s “special attack” operations. They will find this concise yet comprehensive study most enlightening.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments