By Al Hemingway

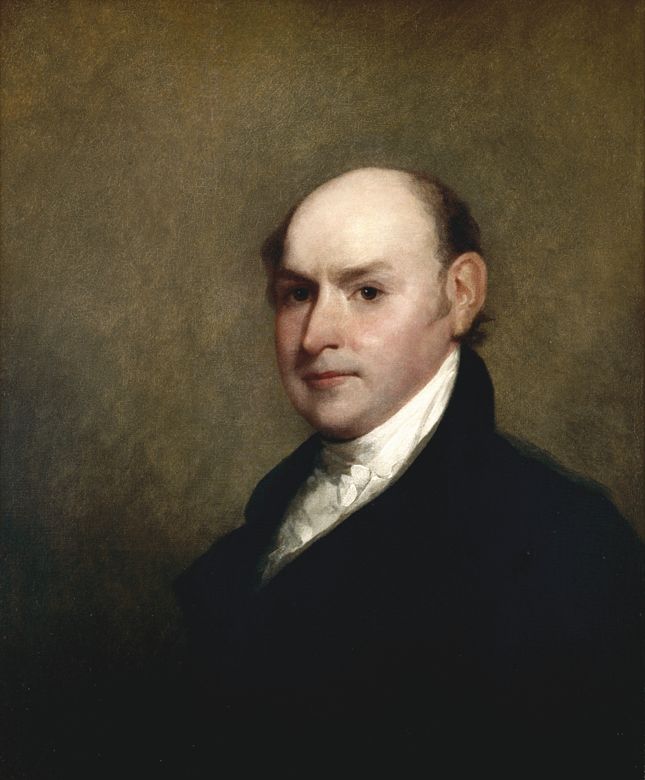

John Quincy Adams, son of the second president of the United States, John Adams, sat across from his counterpart, British Admiral Lord James Gambier, at Ghent, Belgium, desperately attempting to hammer out a peace treaty that would end the War of 1812. The United States had declared war on Great Britain for the second time in the country’s short history for myriad reasons, the main one being the impressment of American sailors by British ships on the high seas.

Adams, arguably America’s foremost foreign affairs expert, was appointed the nation’s chief negotiator by President James Madison. For nearly two years, the two sides met to discuss terms to end the conflict. Although the British had won decisive battles in Maryland and along the U.S.-Canadian border, and had even put Washington to the torch, the fledgling American Navy had performed magnificently against the powerful British, winning decisive sea battles and seizing much-needed war matériel.

Adams, arguably America’s foremost foreign affairs expert, was appointed the nation’s chief negotiator by President James Madison. For nearly two years, the two sides met to discuss terms to end the conflict. Although the British had won decisive battles in Maryland and along the U.S.-Canadian border, and had even put Washington to the torch, the fledgling American Navy had performed magnificently against the powerful British, winning decisive sea battles and seizing much-needed war matériel.

An agreement was finally signed on Christmas Eve 1814, although news did not reach American shores in time to prevent the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, when General Andrew Jackson and a polyglot force of volunteers soundly defeated the cream of the British Army. Adams had performed a minor miracle, even though the treaty was certainly not definitive for either side.

Historian Harlow Giles Unger has written an admiring new biography of America’s sixth president entitled John Quincy Adams (Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2012, 350 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, notes, index, $27.50, hardcover). The book covers Adams’s childhood, diplomatic career, term as Secretary of State under President James Monroe, his own presidency, and his time in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

No doubt John Quincy inherited his oratorical skills from his father, John Adams, the Massachusetts lawyer who managed to get an acquittal for the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre in 1770 and later served as a member of the Continental Congress. The elder Adams took his son on a perilous sea journey to France during the Revolutionary War, when both narrowly escaped being caught by a British man-of-war that chased their vessel for several miles. It was in France that John Quincy’s education flourished. He later attended Harvard, becoming fluent in German, French, and Dutch and even speaking some Russian. This linguistic ability, and his unique diplomatic tact and skills, endeared him to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, all of whom offered him numerous overseas assignments during their tenures as chief executive.

As Secretary of State, Adams penned the Monroe Doctrine that forbade European powers “from the attempt to spread their principles in the American hemisphere or to subjugate by force any part of these continents to their will.” As Thomas Jefferson stated, Adams’s “pointed pen” was the deciding factor that made the Monroe-Adams relationship work so well.

As Secretary of State, Adams penned the Monroe Doctrine that forbade European powers “from the attempt to spread their principles in the American hemisphere or to subjugate by force any part of these continents to their will.” As Thomas Jefferson stated, Adams’s “pointed pen” was the deciding factor that made the Monroe-Adams relationship work so well.

Adams squeaked out a victory in the 1824 presidential election when his longtime friend Kentuckian Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House, threw his support behind the Massachusetts native. This infuriated Andrew Jackson, Adams’s opponent, who called it a “monstrous union” and vowed to destroy his administration by ensuring that any legislation would not pass either the House or Senate. Jackson’s supporters made this threat a reality, and Adams’s term in office did little to advance the fortunes of the country. He was denounced for being out of touch with his America, and his dream of advancing the nation, culturally and economically, was shattered by hyper-partisanship.

As Unger points out, Adams, although a staunch Federalist, was not a down-the-line party man. Instead, he was a person of conscience who tried to cast his vote for the betterment of the United States and its citizens. This was evident in his ardent opposition to slavery, which he called a “great and foul stain.” It was his passionate appeal before the Supreme Court in 1841 that gained freedom for 36 Africans who had rebelled and hijacked a ship while being transported to the United States to become slaves. The men freed themselves and killed the captain and three crew members of Amistad, the ship on which they had been imprisoned. Adams’s magnificent speech had many in the courtroom sobbing, and prosecutors realized that they had lost their case.

While attempting to stand and answer the roll call in the House one cold, wintry day, the 80-year-old Adams suddenly collapsed. He was carried to the Rotunda, then to the Speaker’s office, and muttered his last words before lapsing into a coma: “This is the end of earth, but I am composed.” He died several days later on February 23, 1848. Despite being a failed president, the eloquent orator from Braintree, Massachusetts, left an indelible mark on the nation.

Ground Pounder: A Marine’s Journey Through South Vietnam, 1968-1969 by Gregory V. Short, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2012, 368 pp., map, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Ground Pounder: A Marine’s Journey Through South Vietnam, 1968-1969 by Gregory V. Short, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2012, 368 pp., map, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

As a Vietnam veteran and former Marine who served in Northern I Corps in 1969, I found this to be one of the best memoirs written by a veteran who was also “in country” during the 1968-1969 period. Short’s experiences while serving with different units as a ground pounder, or infantryman, and in a rear-echelon unit in Da Nang, give readers good insight into what life was like for a Marine enlisted man in the Vietnam War.

Short’s accounts of life in the bush and in the rear are excellent, but it is his depiction of his return home that will really ring true for veterans of that unpopular war. His disillusionment, confusion, and attempts to reconnect with family and friends are emotions many veterans shared. And like other veterans, Short keeps asking himself why we were there. Was the tremendous sacrifice really worth all the lives lost?

Short’s book should be required reading in high schools and colleges. It well describes the futility of a war that could have no long-term success, given the strategy—or lack thereof—of politicians attempting to bring the grimly determined North Vietnamese to their knees. It is also castigates those who called returning veterans “baby killers.” “It wasn’t our fault that in the final analysis we were put in an impossible situation, a situation created by forces beyond our control,” writes Short. “Needless to say, the deep emotions that I had felt during my years in the Marine Corps would persist in me for a very long time.” Most Vietnam veterans can relate to that.

The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation by James Donovan, Little, Brown and Co., New York, 2012, 500 pp., maps, illustration, photographs, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover.

The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation by James Donovan, Little, Brown and Co., New York, 2012, 500 pp., maps, illustration, photographs, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover.

Few American battles garner more attention than the 13-day plight of the 200-odd defenders of the Alamo, who held out against thousands of Mexican soldiers led by the self-proclaimed “Napoleon of the West,” General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. For nearly two weeks, Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis, Jim Bowie, David Crockett, and others holed up in the 18th-century adobe structure in San Antonio and repeatedly fought off the enemy hordes before finally succumbing to an all-out pre-dawn assault the killed nearly every defender in less than an hour.

Everyone knows that part of the story, but historian James Donovan does an excellent job at knitting together all the events, the history, and the participants on both sides and why they met at the old Spanish mission on that fateful March day. He describes the flaws of all the major players, both Mexican and American, particularly the political in-fighting within the newly formed provisional government of Texas, whose governing body could not reach an agreement about anything, and the self-serving sycophants who surrounded Santa Anna, an egotistical peacock and ladies’ man.

Donovan closely examines two items that have been hotly disputed for years regarding the battle: Travis drawing his fabled line in the sand and the existence of Moses Rose, who allegedly made good his escape from the fort. The author concludes that both events did indeed take place. As with much about the Alamo, truth continues to be stranger than fiction.

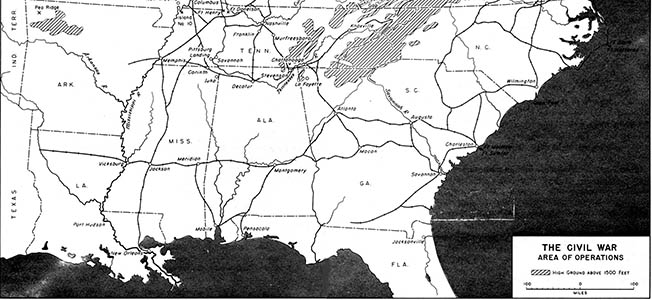

The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History by Louis S. Gerteis, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2012, 250 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History by Louis S. Gerteis, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2012, 250 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

When historians and Civil War buffs discuss the major battles of the war, the state of Missouri is largely overlooked. Despite the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861, most of the fighting in the state, albeit very bloody, was reduced to guerrilla warfare. University of Missouri history professor Louis S. Gerteis asserts that Missouri’s status as a border state was crucial to the Union, and that conventional forces from both sides attempted to outmaneuver each other to gain the upper hand. At stake was the fertile land in the Missouri River Valley, where the flow of Confederate supplies could go on indefinitely if not stopped.

Gerteis makes a solid argument that Missouri was much more than just a sideshow of the conflict. According to the Federal Civil War Sites Advisory Commission, Missouri ranked third in important battles, with three of them listed at the “highest level of significance.” The invasion of the Confederate Army led by the portly Maj. Gen. Sterling Price of the Missouri River corridor and his subsequent defeat at Westport in October 1864 by the Union Army all but sealed the Southern collapse in Missouri. The savage fighting would continue as bands of irregulars rode the countryside dispatching their own brand of cruel justice to the population, even after the end of the war.

Many Were Held by the Sea: The Tragic Sinking of the HMS Otranto by R. Neil Scott, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., New York, 2012, 264 pp., photographs, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover.

Many Were Held by the Sea: The Tragic Sinking of the HMS Otranto by R. Neil Scott, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., New York, 2012, 264 pp., photographs, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover.

On the stormy night of October 6, 1918, one of the worst maritime disasters of the era occurred off the coast of Scotland, near the small village of Islay. HMS Kashmir was transporting American and English soldiers to Liverpool, England, in the waning days of World War I. Kashmir saw land, but was it the coast of Scotland or Northern Ireland? The raging storm, with its strong winds and gigantic waves, obscured everyone’s view. Fortunately, Kashmir made the right decision, figuring it was Scotland, and changed course to a southerly direction. Another ship, HMS Otranto, did not and veered off to the north. A 60-foot wave slammed Kashmir’s bow into Otranto, spinning her around like a top. The accident resulted in the deaths of nearly 500 men.

The author has written a moving and thought-provoking book that carefully describes the terrible tragedy and the heroism of Scottish townspeople who braved the frightful storm to rescue surviving servicemen who washed ashore. Also delineated are the efforts of the local police, who had the grisly task of identifying victims and notifying their kin in England and the United States. This is an intriguing story about a little-known naval disaster and its all-too-human aftermath.

Memories From the Forgotten War: A Memoir by Harris R. Stearns, Vantage Press, New York, 2012, 120 pp., photographs, $14.95, hardcover.

Memories From the Forgotten War: A Memoir by Harris R. Stearns, Vantage Press, New York, 2012, 120 pp., photographs, $14.95, hardcover.

Stearns has written an unusual account of his experiences during the early stages of the Korean War. Instead of writing his memoirs as a first-person account, he has opted to write his book in the third person. The author saw considerable action as a member of the 89th Tank Battalion and was wounded by shrapnel during a mortar attack on his position. He explains in detail the deplorable conditions of the Sherman tanks when he first arrived in South Korea. Many had nonworking radios, bad voltage regulators, deteriorated fan belts, and no ammunition with the exception of armor-piercing shells, which were useless against infantry assaults by the North Korean Army.

Stearns participated in the Battle of Chinju from August 5 until September 19, 1950, near the all-important Masan-Chinju Railroad line. Elements of the 25th Infantry Division, supported by South Korean forces, were finally able to halt the enemy advance. The resulting victory gave the Marines time to land at Inchon, recapture Seoul, and rapidly pursue the retreating North Korean Army.

Surviving the war, Stearns was discharged from the Army and moved back to his native New York. He retired in 1986 as assistant chief on the Gloversville Fire Department after more than 20 years of service. His look at the Korean War from one soldier’s point of view sheds new light on another aspect of that sadly forgotten conflict.

The Business of Martyrdom: A History of Suicide Bombing by Jeffrey William Lewis, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, charts, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

The Business of Martyrdom: A History of Suicide Bombing by Jeffrey William Lewis, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, charts, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Suicide bombers are not new to history. What is new, however, is the technology used to build and ignite their explosive devices. The author, an instructor in International Studies at Ohio State University, delves into the reasons that certain individuals choose to become martyrs, the terrorist organizations who recruit them, and the societies that allow, and even idolize, such murderous methods to achieve their goals. He has penned a fascinating and frightening story of a sinister world that is bent on toppling governments and entire societies by enlisting the aid of radicalized people who are willing to kill themselves to gain what their religions promise to be eternal glory.

Since ancient history, mankind has had many martyrs. Not until World War II, however, when the Japanese used kamikaze pilots to attack American ships, were suicide attacks used on such a large scale. Today, radical groups from Al Qaeda to the Taliban and other largely Muslim factions have rediscovered the technique to carry out attacks against those they view as oppressors.

Over-the-counter technology for terrorist cells is the core to manufacturing dangerous weapons that can inflict the most damage, Lewis says. The author writes that today’s radicals possess the best of both worlds by using “precision and sophistication” as well as “simplicity and reliability” to ensure the success of their mission. They are a difficult enemy to defeat, since they rely on unconventional means to conduct their war. As one Irish Republican Army bomber quipped: “[We] would be nowhere without Radio Shack.”

Burgoyne and the Saratoga Campaign: His Papers by Douglas R. Cubbison, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2012, maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

Burgoyne and the Saratoga Campaign: His Papers by Douglas R. Cubbison, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2012, maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

According to many historians, the Battle of Saratoga, fought on September 19, 1779, was the turning point in the American Revolution. After British General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne surrendered the remnants of his army, a previously uncommitted France entered the conflict on the American side. The author has collected unpublished letters and paperwork by Burgoyne that he intended to use in his defense when he was held accountable by Parliament for the disastrous loss at Saratoga.

Prior to his arrival in North America, Burgoyne had no experience in the type of warfare being waged there. Although Burgoyne was certainly not a great commander, historians now hold Lord George Germain equally accountable in the humiliating loss at Saratoga. As Cubbison writes in his introduction, Germain’s handling of the British war effort was “vacillating, indecisive, and lacked insight into the actual conditions to be found in the North American theater.”

Germain would prevent Burgoyne from seeking a court-martial to clear his name. Could it be that Germain’s inadequate leadership might have come to light? We will never know. In the end, “Gentleman Johnny” would go on to have a career as a successful playwright, a vocation that appeared to suit him much better than that of an officer in the British Army.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments