By Al Hemingway

After the successful invasion of North Africa in November 1942, Allied planners immediately set to work developing a strategy to deliver a new offensive blow against Nazi Germany. There were only two ways that this could be done: through the Balkans, which would sandwich the enemy between the Allies and the Soviet Union, or by striking at Sicily and facilitating an invasion of the Italian mainland. Adolf Hitler and his staff realized an attack was imminent—but from where? Any large buildup of forces would tip the Allies’ hand, and the Germans could reinforce the region, making the operation a risky one.

Since Sicily had already been chosen as the objective, something had to be done to convince the enemy that the invasion was to take place through Greece. What British Intelligence devised was arguably the most outlandish plan ever conceived to dupe the German Army into believing the main thrust would be through the Balkans.

Since Sicily had already been chosen as the objective, something had to be done to convince the enemy that the invasion was to take place through Greece. What British Intelligence devised was arguably the most outlandish plan ever conceived to dupe the German Army into believing the main thrust would be through the Balkans.

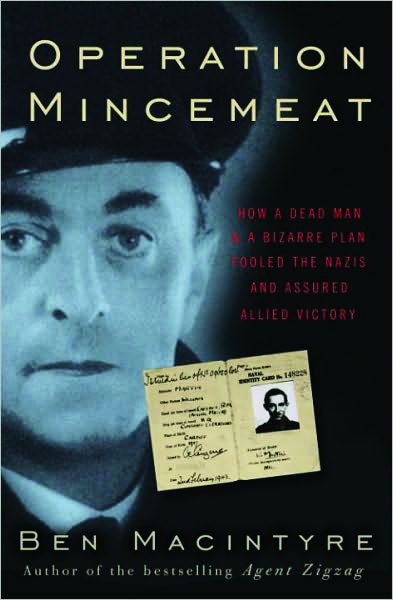

Author Ben Macintyre has written a dazzling account of this scheme titled Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (Harmony Books, New York, 2010, 416 pp., photographs, maps, notes, index, $25.99, hardcover). He delves into great detail on all the members of the team who created Mincemeat. Probably never in the annals of clandestine operations did such a quirky group exist.

It included Flight Lieutenant Charles Cholmondeley of the Twenty Committee, a small department within British Intelligence, who kept track of all the double agents. Although it was first dismissed, Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu of the Royal Navy was intrigued by the idea and decided to pursue it with Cholmondeley. The pair developed a plan to have the dead body of a courier, whose plane had crashed at sea, found floating off the Spanish coastline. This “corpse” would be carrying seemingly sensitive documents describing an assault on Greece. Montagu knew that the Spanish authorities, although neutral, cooperated with German intelligence, known as the Abwehr, and dutifully passed along any information that came into their hands.

Macintyre explains the intricate plot twists and methods the Twenty Committee utilized to make both the Spanish and the Germans believe that the Allies were coming ashore in Greece. The “dead body” would have the identity of a Royal Marine major named William Martin. Not only were there the “invasion letters” in his bag, but the team placed numerous “personal items” that “Martin” used while on leave in London.

William Martin was actually Glyndwr Michael, a 36-year old Welshman, who had eaten rat poison and died. Michael, an illiterate “ne’er do well,” was estranged from his family and living in London. To enhance “Martin’s” character even further, the group gave him a fiancée named “Pam,” whose picture he had in his possession when his body was pulled from the water. In reality, “Pam” was Jean Leslie, an attractive clerk, who worked in British Intelligence.

When “Martin” was lost, his death notice was put in the London Times to add further authenticity to the story. It was soon learned that Major Karl-Erich Kuhlenthal, the top Abwehr agent in Spain, believed the contents of the briefcase were genuine. After copies were made of the briefcase’s contents, it was returned to the British attaché in Madrid by Spanish authorities. British intelligence confirmed that the satchel had been opened and examined and reclosed. Allied leaders were sent a message: “Mincemeat swallowed whole,” meaning that the Germans had taken the bait.

The operation was a resounding success, as the enemy diverted some of its forces from Italy to bolster the troops already stationed in Greece in anticipation of the impending invasion. Montagu wrote a book after the war titled The Man Who Never Was. It was so popular that it was made into a movie with Clifton Webb portraying Montagu.

The identity of “Major Martin” was kept a secret until 1996, when a historian unearthed evidence that Michael was indeed the dead man. In January 1998, the British government added a postscript to Michael’s gravestone that read: “Glyndwr Michael served as Major William Martin.”

The unemployed, alcoholic vagrant, who had come from a dysfunctional family, and had never amounted to anything, had become a war hero in death.

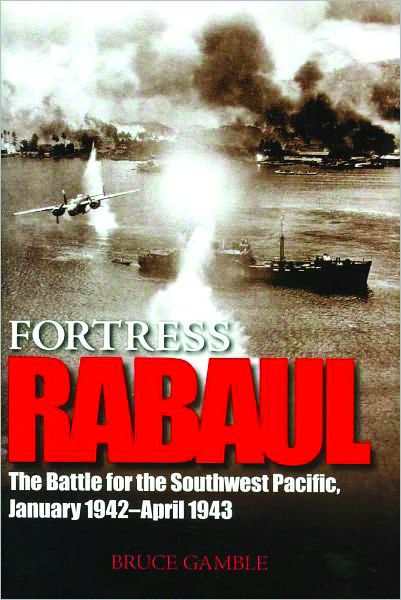

Fortress Rabaul: The Battle for the Southwest Pacific, January 1942-April 1943 by Bruce Gamble, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 398 pp., photos, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Fortress Rabaul: The Battle for the Southwest Pacific, January 1942-April 1943 by Bruce Gamble, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 398 pp., photos, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

The Japanese fortress of Rabaul, situated on the northwest coast of New Britain island, was considered by many to be impregnable. In January 1942, a large Japanese force landed at Rabaul and quickly seized it. The defenders, Australian soldiers known as Lark Force, were no match for the enemy’s overwhelming numbers and capitulated. Some of these men were later massacred by the Japanese.

Allied planners had contemplated invading the Japanese stronghold but realized that the cost in human life and material would be astronomical. Instead, an intense bombing campaign was undertaken. Throughout the conflict in the Pacific, Allied bombers and fighters struck Rabaul repeatedly.

From this massive air campaign, numerous pilots achieved fame with their aerial exploits. American Lt. Cmdr. Edward “Butch” O’Hare, downing five Japanese Betty Bombers, was the first naval aviator to become an ace and Medal of Honor recipient. Sadly, O’Hare’s F4F-3 Wildcat was lost when he was commanding the first night fighter attack launched from an aircraft carrier. In September 1949, Orchard Depot Airport in Chicago was renamed O’Hare International Airport in his honor.

New Hampshire native Army Air Force Captain Harl Pease, Jr., was a B-17 bomber pilot when he earned his Medal of Honor. On a bombing mission over Rabaul, Pease and his crew were set upon by 30 enemy fighters. After downing several, his aircraft reached its destination and successfully dropped its bomb load. On the return flight, Pease’s Flying Fortress lagged behind its formation and was shot down by another swarm of Japanese Zeros. Pease and his crew bailed out and were captured. It was later learned that they were beheaded after they had dug their own graves.

Gamble’s book is a wonderful tribute to these and all the other pilots and crews, both land-based and carrier airmen, who kept the pressure on the Japanese at Rabaul. By August 1943, the Allies were rapidly advancing through the Pacific. The defenders of Rabaul watched helplessly as their empire slowly began to erode, until the island finally surrendered in September 1945, without firing a shot.

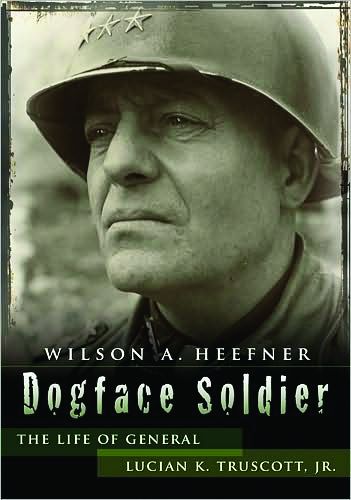

Dogface Soldier: The Life of Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. by Wilson A. Heefner, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2010, 392 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Dogface Soldier: The Life of Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. by Wilson A. Heefner, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2010, 392 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Described as profane and hot-headed with a penchant for alcohol, Lucian Truscott was nevertheless a soldier’s soldier. Although his training bordered on brutal, he shared in the discomforts of his troops because he firmly believed that an officer should lead his men at the front, not from miles to the rear.

Truscott’s talents as a hard-charging officer with a keen eye for terrain did not go unnoticed by his superiors. By the outbreak of World War II, he already had achieved the rank of colonel. During the fighting in Sicily he took over the reins as commander of the 3rd Infantry Division and led it through much of the Italian Campaign. Here he developed the “Truscott Trot,” in which infantrymen marched five miles per hour over the first mile and four miles per hour after that, far more than the standard 2.5 miles per hour required.

After the assault on Anzio, Truscott took charge of VI Corps when Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas was relieved of command. His usual fiery command style reaped benefits as his corps broke out of the beachhead and made its way up the Italian boot. Soon after, VI Corps served as the spearhead for Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France, in August 1944. Once again, Truscott’s leadership skills paid off as his troops performed admirably.

The author has done a remarkable job in researching this factual account of the life of one of America’s best but little-known generals. He was able to gain the cooperation of the family and obtain access to Truscott’s personal papers. All of this extensive research has produced a great book about a great man, Lucian Truscott.

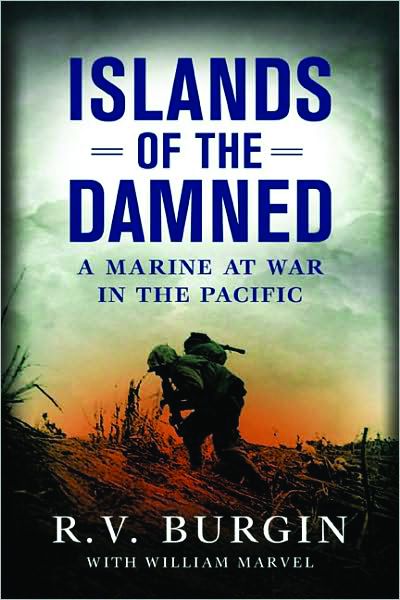

Islands of the Damned: A Marine at War in the Pacific by R.V. Burgin with Bill Marvel, Caliber, New York, 2010, 296 pp., photos, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Islands of the Damned: A Marine at War in the Pacific by R.V. Burgin with Bill Marvel, Caliber, New York, 2010, 296 pp., photos, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

There have been many great autobiographies dealing with those who served in war. These individuals have described what it was like to participate in some of the biggest battles in history—and have lived to tell about it. Only they can vividly describe the horror of combat, the unforgiving terrain, and the death of a good friend. Most have waited years to collect their thoughts and put their words on paper after trying to forget what they had experienced.

Such a man was Romus Valton Burgin. As a young man growing up in rural Texas, Burgin was accustomed to a hard life and discipline, so he enlisted in the Marines. His decision would place him in some of the biggest campaigns the Marine Corps fought during the Pacific War: Cape Gloucester, Peleliu, and Okinawa. It was on Okinawa that Burgin was presented with a Bronze Star for eliminating a Japanese machine-gun nest.

Burgin served with Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division, as a mortar man during the fighting to secure these islands. One of his comrades was Eugene “Sledgehammer” Sledge, who also wrote a magnificent account of his time in the Pacific titled With the Old Breed: On Peleliu and Okinawa. Many consider it one of the finest books ever written about World War II. Islands of the Damned may well rank with Sledge’s book. It is a gritty, no-holds-barred description of the bloody struggle to beat the Japanese from an infantryman’s point of view. Kudos to Burgin for overcoming his anxiety and fears and writing it.

Hitler’s Holy Relics: A True Story of Nazi Plunder and the Race to Recover the Crown Jewels of the Holy Roman Empire by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2010, 352 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $27.00, hardcover.

Hitler’s Holy Relics: A True Story of Nazi Plunder and the Race to Recover the Crown Jewels of the Holy Roman Empire by Sidney D. Kirkpatrick, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2010, 352 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $27.00, hardcover.

Lieutenant Walter Horn, a German-born intelligence officer who had fled Nazi Germany prior to the war, can easily be called a modern-day Sherlock Holmes. In civilian life, Horn was an art history professor at the University of California at Berkeley and had also studied the subject in Hamburg, Munich, and Berlin, and done postgraduate work in Florence, Italy.

While Horn was interrogating a German soldier, he discovered that Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, had been maintaining a top secret underground bunker some 200 feet beneath the Nuremberg castle. The bunker contained priceless works of art that the Nazis had stolen from occupied countries. The SS soldier’s parents, who lived above the classified storage area, were charged with the upkeep of the ventilation system and checking to ensure that the objects did not have mold or insect damage.

From this, Horn began a chase to uncover the Nazi plunder, particularly the Crown Jewels of the Holy Roman Empire and the Spear of Destiny, reputed to have been the one that a Roman soldier used to pierce Christ’s side as he hung dying on the cross. In his travels, the former art historian also unearthed the disturbing fact that his own family had helped to undermine scholarly research to support Adolf Hitler’s claim of Aryan supremacy and the creation of a master race.

This is a remarkable story that has been buried for decades. However, with the assistance of Horn’s widow and his children, Kirkpatrick was able to piece together the facts and finally reveal the truth.

American Guerilla: The Forgotten Heroics of Russell W. Volckman by Mike Guardia, Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia, PA, 2010, 240 pp., maps, photos, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

American Guerilla: The Forgotten Heroics of Russell W. Volckman by Mike Guardia, Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia, PA, 2010, 240 pp., maps, photos, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

Russell Volckman is truly a remarkable man. When the Japanese captured the Philippines, the intrepid U.S. Army officer steadfastly refused to surrender. Armed with just a six-shot revolver, he made his way into the unforgiving jungle and raised an army of more than 20,000 Filipinos who wreaked havoc upon the enemy’s occupation forces. It is estimated that his guerrilla force killed 50,000 Japanese before the Allies returned to the Philippines in 1944.

Despite all of this, Volckman’s name is virtually unknown among military historians. If it were not for the diligent research of the author, Volckman’s valuable contributions to the war effort and his tireless work promoting special warfare and counterinsurgency operations would never have been revealed.

Volckman realized that future wars would not be conventional in nature, which prompted him to secretly author two books on the subject. These manuals would soon become the Bibles that would ultimately help in the creation of the first Green Beret unit, the 10th Special Forces Group.

Volckman died in 1982 at the age of 70 with the rank of brigadier general. Due to his secretive nature, few realized his accomplishments and contributions to counterinsurgency development in the U.S. Army. But, thanks to Guardia, Volckman now holds a coveted place in its history, as the true father of Special Forces.

Short Bursts

The Diary of Prisoner 17326: A Boy’s Life in a Japanese Labor Camp by John K. Stutterheim, Fordham University Press, New York, 2010, 235 pp., maps, photos, glossary, $35.00, hardcover.

The Diary of Prisoner 17326: A Boy’s Life in a Japanese Labor Camp by John K. Stutterheim, Fordham University Press, New York, 2010, 235 pp., maps, photos, glossary, $35.00, hardcover.

When the horrendous ordeals of prisoners of war are discussed, it is rarely mentioned that thousands of Europeans, indigenous people, and those from other Asian nations underwent brutal hardships at the hands of the Japanese.

Finally a book has been written that chronicles the harsh life of a young Dutch boy who survived such a nightmare. Separated from his family, John Stutterheim describes in vivid detail the daily schedule of being a prisoner in a Japanese camp. It is truly an inspirational story of courage and determination to survive and to sit down decades afterward and write his account so others might know the truth of what had transpired.

This should be a must-read for today’s youth who are transfixed in their self-centered world, surrounded by iPods, cell phones, and video games, to fully understand what can happen when outside forces shatter their seemingly safe world and transform it into a living nightmare.

The Pacific War: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima edited by Daniel Marston, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 272 pp., maps, photos, notes, bibliography, $19.95, softcover.

The Pacific War: From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima edited by Daniel Marston, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 272 pp., maps, photos, notes, bibliography, $19.95, softcover.

A dozen noted military historians, Japanese, American, British, and Australian, have collaborated to reevaluate the Pacific Theater campaigns of World War II. Beginning with the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and extending to the conflict’s end when the atomic bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the authors have written chapters that deal with their specific fields of expertise.

The book is full of photos and richly detailed maps, so the reader can follow along with the text. The final chapter is most intriguing. It details the invasion of Japan, Operations Coronet, the plan to seize Tokyo, and Olympic, the landings on the island of Kyushu. To augment their regular forces, the Japanese also trained their civilian population in suicide attacks. Thankfully, the two atomic bombs, although devastating, ended the war and prevented what was sure to be a major bloodbath.

This one-volume overview of the Pacific War is a must for any history buff’s personal library. It further benefits students in gaining understanding of the war period.

Surviving the Reich: The World War II Saga of a Jewish-American GI by Ivan Goldstein, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 240 pp., photos, bibliography, $26.00, hardcover.

Surviving the Reich: The World War II Saga of a Jewish-American GI by Ivan Goldstein, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 240 pp., photos, bibliography, $26.00, hardcover.

Here is a truly inspirational book that focuses on one American soldier of the Jewish faith who had to deal with anti-Semitism, not only from the enemy but from his own company commander. When the war broke out, Ivan Goldstein enlisted at 17 years of age. He was assigned to the 41st Tank Battalion, 11th Armored Division. He was shipped overseas, and soon his M4 Sherman tank named “The Barracuda” was involved in the Battle of the Bulge.

On the very first day of the German offensive in December 1944,

Goldstein’s tank took a direct hit and was set ablaze. The vehicle soon became stuck in a frozen pond. Goldstein managed to free himself from the inferno, only to be taken prisoner. He miraculously escaped death on numerous occasions, especially when the Nazis discovered he was Jewish, and ultimately survived the war.

Goldstein returned to Belgium when he discovered that his tank, The Barracuda, had been salvaged and was on display in the town of Bastogne as a memorial to the American troops who fought and died there. The book is a moving tribute to one man’s extraordinary bravery to survive his harrowing ordeal.

Battle of Britain: Commemorative Collection by Robert Taylor, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2010, 128 pp., illustrations, photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Battle of Britain: Commemorative Collection by Robert Taylor, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2010, 128 pp., illustrations, photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Wonderful pen and ink sketches, detailed paintings, and great photographs illustrate artist Robert Taylor’s Battle of Britain. Taylor’s works have been compiled into this edition to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the pivotal air battle of the war in Europe. It is indeed a fitting tribute to those outnumbered British fliers who met and defeated the German onslaught in the skies over England in 1940.

For the introduction, writer Michael Craig wrote: “Hopefully, this newly assembled but historically evocative collection of Robert’s paintings will go a long way to ensure that the memories and importance of the Battle of Britain, and the young men who flew and fought it, will remain embedded within the soul of the British people for many generations to come.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments