By Dante Brizill

The African American Tuskegee Airmen took the fight to a well-trained and deadly enemy with a ferocity and tenacity that World War II aerial combat required. They had to overcome segregation, endless training, racism, a delayed deployment to combat operations, obsolescent planes initially, and attempted sabotage by some in the chain of command before their greatness could be truly displayed. Willie Ashley, Jr., Harold H. Brown, and Charles McGee were just three of the men who carved their legacy in the sky:

On July 3, 1942, Willie Ashley, Jr., of Sumter, South Carolina, graduated as a member of the Single Engine Section Cadet Class SE-42-F at Tuskegee Army Air Field, in Tuskegee, Alabama. He was among the first to fly solo, receive his pilot’s wings, and earn his second lieutenant bars. Serving with the legendary 99th Fighter Squadron, he became one of the first Tuskegee Airmen to engage enemy fighters in the Italian theater.

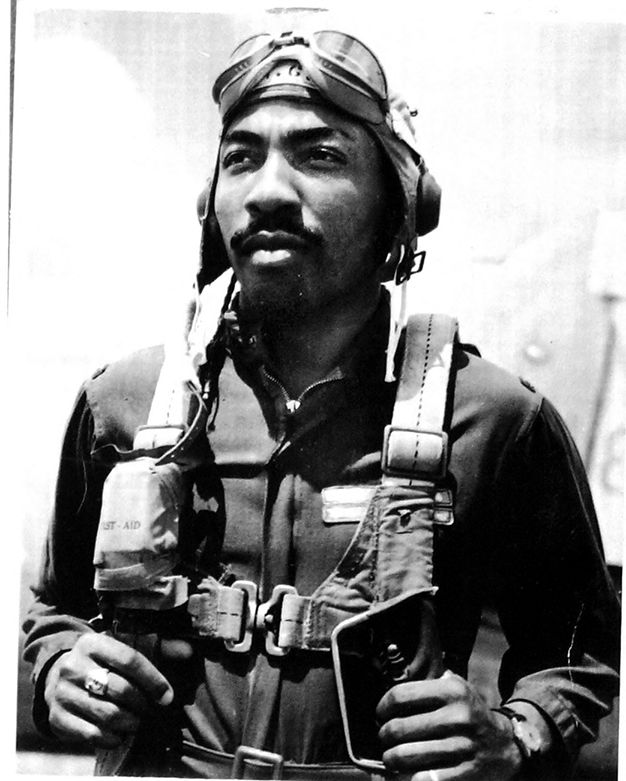

Lieutenant Harold H. Brown of Minneapolis, another Tuskegee graduate, struck enemy targets on the ground and protected American bombers in the air. Being one of America’s first trained African American pilots, he flew with the famed 332nd Fighter Group. Shot down on his 30th mission over enemy territory, he safely bailed out of his stricken P-51 and survived months as a prisoner of the Germans.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1919, Charles McGee was an engineering student at the University of Illinois when he decided to serve his country, becoming a part of the famed 332nd Fighter Group. He got his start with the Tuskegee Airmen—and went on to become a general.

Brown, Ashley, and General McGee are a small snapshot of the heroism, courage, and devotion to duty of the men of the Tuskegee Airmen. Deemed an “experiment” by many of the military brass, these men proved to each other, doubters, and their country that they were worthy of the trust that was placed in them. These men also changed perceptions of the fighting ability of African American men.

This fact alone would have profound changes on the post WWII military and American society for years to come. Being called an “experiment” seems ridiculous today, but was a reflection of the little faith placed in the fighting capabilities of African Americans at the dawn of World War II, and well into the war.

In the Beginning

As war clouds engulfed Europe in late 1939, a need arose over the next two years to prepare the United States for a war footing, particularly in aviation. The previous year, President Roosevelt expanded the civilian pilot training program in the United States, and the Army Air Corps, a forerunner of the U.S. Air Force, stepped up pilot training.

Black leaders, Black newspapers, and civil rights organizations demanded that African Americans be included. Segregation was the norm in the U.S. military at the time, and the intelligence and competence of African Americans were questioned.

Blacks had fought in every armed conflict in the United States since the Revolutionary War. They served with distinction in the Civil War and World War I, but the military reflected American society at the time, which deemed African Americans as second-class citizens and incapable of front-line service.

An infamous Army War College study released in 1925 seemed to influence post-World War I beliefs about the fitness, courage, and intelligence of Black soldiers. It stated in no uncertain terms that Black soldiers were inferior and should not be in combat or leadership roles. It even went as far as to describe the anatomy of the Black brain as being smaller than those of whites.

This report was widely accepted by the military and reflected the role that they envisioned for Black soldiers when the U.S. entered World War II—suitable only for menial jobs and nothing requiring intelligence and courage. By the time America became involved in the war, the Black press and civil rights leadership challenged these assumptions and put enormous pressure on the military and the Roosevelt administration to open its doors. One of those doors would be the right to fly.

By September 1940, after much pressure and lobbying, the Army Air Corps announced that it would begin training black pilots at Moton Field, the soon-to-be constructed airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama. This fulfilled a campaign promise President Roosevelt had made. This small rural town in the heart of the Jim Crow South, with only around 4,000 residents, was home to Tuskegee Institute, a prestigious Historically Black College established in 1881, whose first President was Booker T. Washington and who served in that capacity until 1915.

Booker T. Washington was a former slave and one of the most well-known and admired African American educators of the late 19th and early 20th century. In 1940, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Tuskegee Institute and took a flight over the campus with the chief flight instructor, Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson, against the wishes of her aides. Anderson, who was a self-taught pilot, established the flight program at the school in 1939. (He is known today as “the Father of Black Aviation.”) A photo of the two of them appeared in newspapers around the country.

It was not a surprise that the First Lady, to the chagrin of the Secret Service, took the flight; she was ahead of her time in terms of promoting racial equality and progress. Anderson believed that this gesture by Mrs. Roosevelt brought positive attention to Black aviation. Her actions did not start the program, as has been mistakenly cited, but she did use her influence to help raise money to finance the building of Moton Field.

Applications flooded into Tuskegee from all over the country once the new pilot training program was announced. Many of these applicants had college degrees or were undergraduates. Some scored so high on their entrance exams that cheating was suspected and retakes ordered. The program also trained mechanics, maintenance workers, and ground crewmen at Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois, to service the planes the pilots would fly. Over a dozen black nurses were assigned to the base, including 1st Lt. Della Raney, the first Black woman commissioned in the Army Nurse Corps.

An Extraordinary Commander

The Tuskegee Airmen, and the original unit—the 99th Pursuit Squadron—might not have happened without their extraordinary commander, Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr. His father, Davis Sr., would become the nation’s first African American general, promoted to that rank on October 25, 1940. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr’s. journey to Tuskegee started as a youngster who was enamored at what he witnessed at an air show in his home town of Washington, D.C.

With his father in the military and that profession’s constant reassignments, Davis Jr. graduated from high school in Cleveland and attended three colleges: Western Reserve (later Case Western Reserve) University, the University of France, and the University of Chicago.

Following his father’s wishes, Davis pursued an appointment to West Point, passing the required entrance exam, and entering in 1932. As the lone Black cadet, he was not welcomed there and ostracized during his four years, eating alone and having no roommate. His fellow cadets even refused to speak to him, but he persevered and graduated in 1936, ranking 35th out of 236.

Prior to his graduation, he spent some time at an Army Air Corps base and obtained some flying experience, which convinced him that he’d rather be in the air than in the infantry. He applied that fall for the Army Air Corps and passed all the requirements, but his application was rejected; there were yet no plans for Black pilots.

But Davis Jr. never gave up on his dream to fly. The Army clearly had no idea what to do with a talented young Black officer on the eve of World War II, and did not realize the potential he possessed. Instead, they assigned him to the all-African American 24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, Georgia. Later, he was assigned to the Tuskegee Institute to teach military tactics to Black civilian pilots.

While teaching at Tuskegee, he was not far from Kennedy Field where the Black civilian pilots were being trained. After a brief stay at a Kansas post with his wife, Agatha Jo Scott Davis, he got his dream assignment.

In early 1941, the Roosevelt administration ordered the War Department to create an all-Black flying unit. Captain Davis was released from his previous duties and began pilot training at Moton Field, the new airfield for Black pilots at Tuskegee.

His dreams of being a flyer were starting to come to fruition. In July 1941, he entered training with Tuskegee’s first aviation class, graduating in March 1942 with Captain George S. Roberts, 2nd Lt. Charles DeBow Jr., 2nd Lieutenant Mac Ross, and 2nd Lieutenant Lemuel R. Custis. These men would be America’s first African American military pilots.

In July, Davis was promoted to lieutenant colonel and named commander of a new unit: the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

By July 1942, the fourth class of pilots had graduated from the training program and the 99th Pursuit Squadron was now up to full strength. The men were ready to fight and put all of their months of training to use. Unfortunately, there were no immediate plans to deploy the men into combat.

This was typical of the experience of many African American units in the war. They had to wait for orders that might or might not come. To add insult to injury, being based in a Jim Crow town in the Deep South that was openly hostile and violent toward the men and women of color stationed there did not help matters. A Black MP was beaten in the town by two Alabama Highway Patrol officers. A black nurse stationed at the base, Lieutenant Norma Greene, trying to get back to the base after a shopping trip before her shift started, refused to leave a bus in Montgomery that she was told was for “whites only.” The bus driver called the police and she was arrested and beaten.

News of these acts of violence made their way around the base, the Black press, and the NAACP, and sparked understandable outrage. Colonel Frederick von Kimble, the commander of the base who took over in January 1942, strictly enforced segregationist policies on the premises. The menace of not fighting and being subject to racism on and off the base took a toll on the morale of the men, which fell to a dangerously low level. White pilots with similar training and preparation were sent overseas; Blacks were not. But better days were coming.

By 1942 the Allies were on the offensive. The invasion of North Africa in November (Operation Torch) had been a success and the war was shifting to the Italian peninsula. Control of the air over the Mediterranean was key to Allied operations in the region. Finally, there would be an opening for the Tuskegee Airmen to prove their mettle.

Off to War—At Last

Good news arrived on April 1, 1943. The 99th was shipping out—the wait was over. The men boarded a train in Tuskegee and traveled to Brooklyn, New York. On April 15, they boarded a troop ship, the USS Mariposa. Two weeks later, they landed in Casablanca, Morocco. Soon they would get the chance for which they had trained so hard.

By the time the 99th arrived in North Africa, the Italians and Germans had either surrendered or had evacuated to Sicily. The men of the 99th set up camp next to a dirt runway in the desert and quickly went to work. The pilots soon got better planes–P-40 Warhawks that were faster than the BT-13 monoplanes they had trained in.

The 99th spent the month of May training with the nearby all-white 27th Fighter Group that welcomed them. They practiced dogfights and honed their skills. Then, on June 2, 1943, the 99th flew their first combat mission. It took place over Pantelleria, a small Italian island in the Mediterranean Sea, between Tunisia and Sicily.

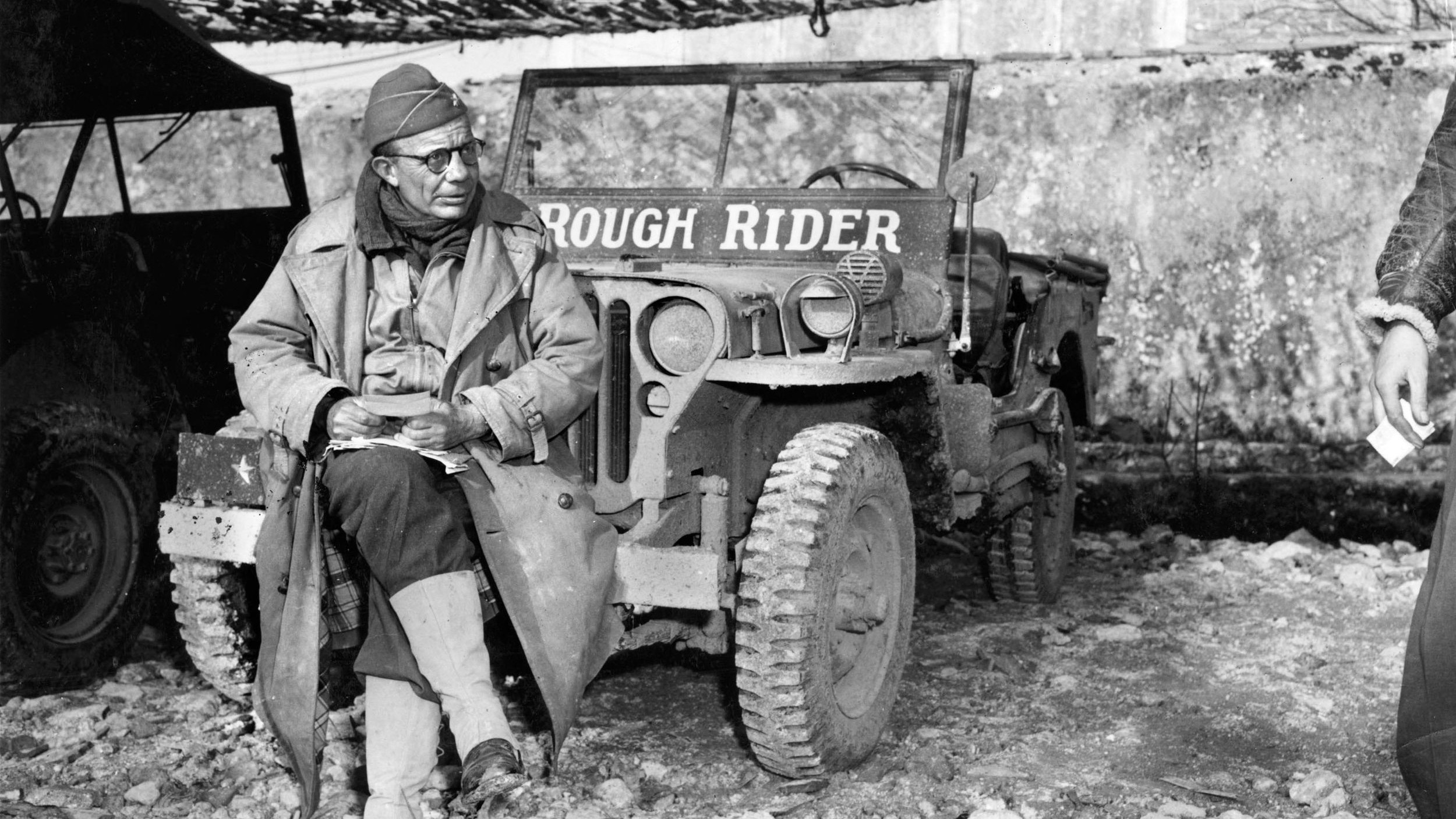

Filled with Axis troops, pillboxes, and underground hangars, Pantelleria was in a key strategic location that needed to be secured, as Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, and the Allies prepared to open the Italian campaign.

Eisenhower, who believed that air power would be sufficient to secure Pantelleria, directed Lt. Gen. Carl “Tooey” Spaatz to use the Allies’ Northwest African Air Forces (NAAF) to do the job. Dubbed Operation Corkscrew, this would be the 99th’s baptism of fire.

Davis and his unit would be a part of this critical mission. This was notable, because it would be the first time African American pilots would be used in combat by the U.S. Army. In early June, while attached to the all-white 33rd Fighter Group, the 99th took out enemy machine-gun positions, dive bombed, escorted bombers on raids, and patrolled the Mediterranean skies.

A week into their first mission on June 9, 1943, the 99th encountered the dreaded German fighter, the Me109. As described by Tuskegee Airmen Charles Dryden, “Instantly, without any hesitation, six P-40s wheeled around ‘on a dime’ in a gut-wrenching, 180-degree tight turn to confront the enemy, the pilots flicking their gun switches and gun sights ‘on’ as they prepared for this first air battle with the enemy by any of the 99th pilots. Suddenly facing the 36 .50-caliber machine guns of our flight, the attacking planes scattered. So did we, as we took off after them.”

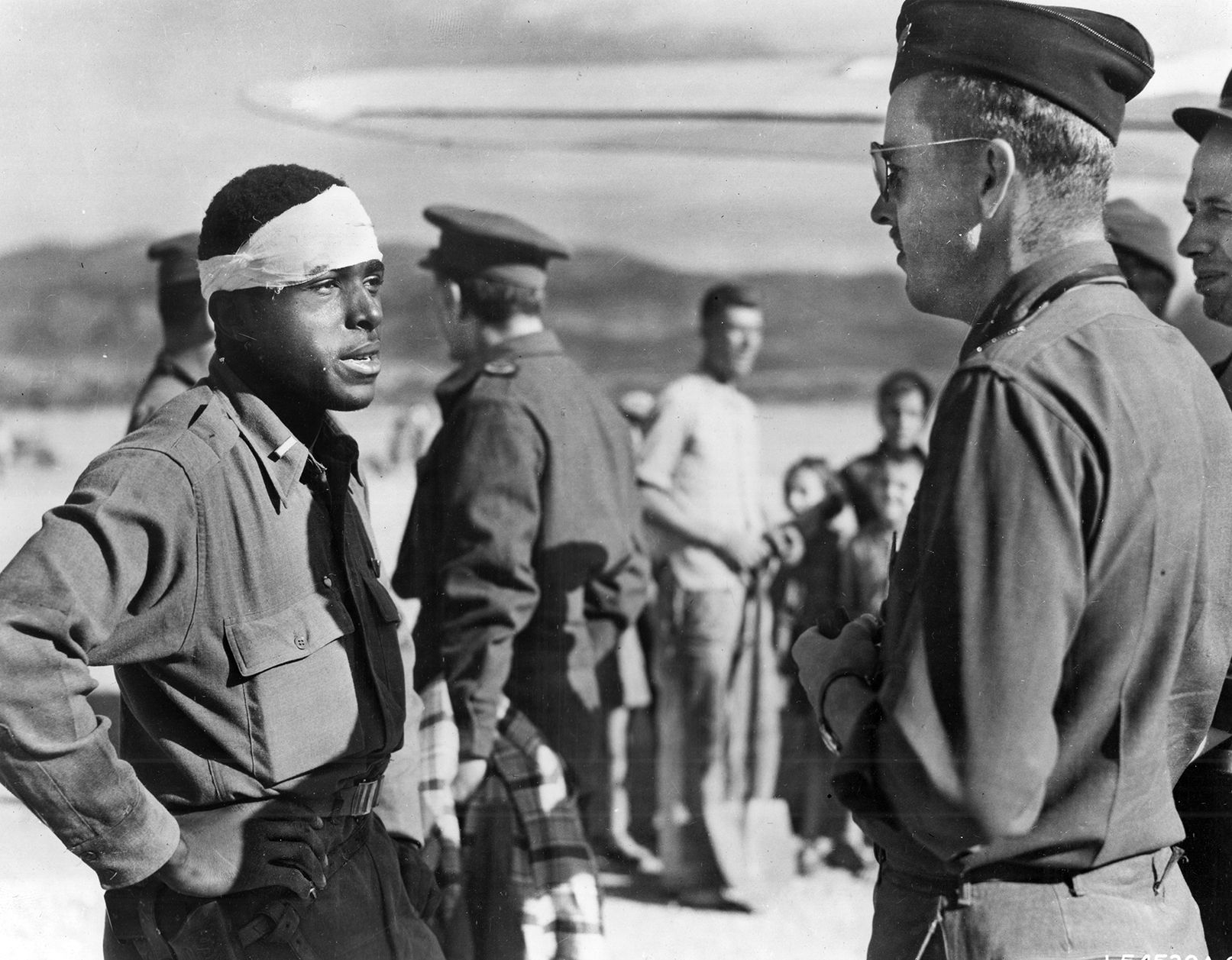

Three weeks later, on July 2, their first kill was recorded over Sicily by 1st Lt. Charles Hall, a pre-med student prior to joining the Army Air Corps. “It was my eighth mission, but the first time I had seen the enemy close enough to shoot at him,” Hall said. This was front-page news among Black newspapers across the country. General Eisenhower wanted to meet the man “who shot down that Jerry,” as he greeted the 99th on their return to base.

The news would prove to be bittersweet as two of their men did not return from the mission. Lieutenants Sherman White and James McCullin were killed in a midair accident. Black war correspondents embedded with the unit proudly reported on their triumphs to their readership and lamented how, maybe, the success of these airmen would reduce prejudice at home for African Americans.

Davis, the pilots, the mechanics, and the ground crews knew that the pressure to perform at a high level would only increase due to the fact that they were finally contributing to the war effort after months of training and waiting, that millions of Black Americans took pride in their achievements, and that there were still doubters about their fitness to serve.

On June 11, 1943, the Italian and German garrison of 11,200 on Pantelleria surrendered, shortly before Allied troops were scheduled to take it by amphibious assault. The air strategy championed by Eisenhower worked. The 99th no doubt contributed to this key victory.

Before they could enjoy their triumph, however, the Tuskegee Airmen would be called upon to defend their honor. Colonel William Momyer was the commander of the 33rd Fighter Group to which the 99th was assigned. As one of the airmen recalled, he was not thrilled with this arrangement, and made no secret about his disdain for having black pilots under his command.

He repeatedly sought ways to embarrass the unit and undermine confidence in their ability. Briefings were moved up without notice to the Black pilots so they would appear late. Davis, being the West Pointer that he was, was outraged by this, knowing how much punctuality and being early to briefings were ingrained in the officer code—being “on time” actually meant being late.

After Sicily was secured in late July (the 99th was attached to the all-white 324th Fighter Group during Operation Husky and for the first time began flying bomber-escort missions), Momyer only assigned white pilots to fly missions up the Italian peninsula to notch more victories and keep the Black pilots away from combat missions. Clearly, he was setting them up for failure that he would later gleefully report to his superiors.

Unfavorable Report

In September, Momyer wrote to Maj. Gen. Edwin House, Commanding General of the 12th Air Support Command, to recommend that the 99th be returned to coastal patrolling duties. He accused them of being the worst squadron under his command and questioned their stamina, fighting ability, and “desire for combat.”

Momyer’s unfavorable report made its way up the chain of command and was accepted as fact without question. Some of the same racist assumptions that were in the infamous 1925 report mentioned earlier were repeated once again. The Momyer report was leaked to Time magazine, prompting an angry response from Colonel Davis’s wife, who strongly defended her husband and his unit.

In October 1943, Davis was summoned home to defend the 99th before a War Department committee. Despite being angry at what Momyer had done, Davis kept his composure and calmly corrected the record of his men. He let it be known that his unit had had no combat experience before Pantelleria, and that he had fewer pilots than the white units, resulting in his pilots having to fly more missions, thus addressing the stamina issue head on. He made it clear that everything that was asked of the 99th in combat was performed.

Davis’s testimony worked, and the “experiment” was allowed to continue. Naturally, the Tuskegee Airmen were angry at their combat ability being questioned. “Here I was, fighting for my country, and I was just an experiment!” one of the airmen noted.

After testifying before the committee, Davis was assigned to command the 322nd Fighter Group, composed of the 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter Squadrons, then in training at Selfridge Field, near Mount Clemens in southeast Michigan. There, Davis was able to impart the combat knowledge he had gained in the Mediterranean to the new pilots of the 322nd.

Although Selfridge was a military installation in Michigan and not the Deep South, the segregated base had its share of racial problems. The base commander, Colonel William T. Colman, had given specific instructions that no Black soldier was to be assigned to him as his chauffeur, but someone didn’t get the memo; somehow, Colman, apparently drunk, shot and twice wounded the Black driver, Pfc. William R. McRae. The colonel was brought up on charges of careless discharge of a firearm. He was court-martialed and had his rank reduced to captain.

In the Skies Over Italy

After Operation Avalanche, the Salerno invasion in September 1943, the Italian campaign bogged down and the Germans fought stubbornly for every foot of ground. To break the growing stalemate, Operation Shingle, an end run around the Germans’ Gustav Line, was launched in early 1944 at Anzio.

On January 27 and 28, 1944, a week after the initial Shingle landings, Luftwaffe fighter-bombers raided the crowded Anzio beachhead. The pilots of the 99th, attached to the 79th Fighter Group, shot down 11 enemy planes, led by Captain Charles B. Hall, who claimed two, bringing his aerial victory total to three.

Another Tuskegee man, Lieutenant Charles Bailey, was cited in a report: “At 1425 hours on the afternoon of January 27, 1944, Lt. Bailey caught a FW-190 headed in the general direction of Rome with a 45-degree deflection shot. The pilot was seen to bail out.”

The eight fighter squadrons defending Anzio claimed 32 German aircraft shot down, while the 99th claimed the highest score among them with 13, thus earning a Distinguished Unit Citation.

The 99th would earn its second Distinguished Unit Citation in Italy on May 12–14, 1944, while attached to the all-white 324th Fighter Group, attacking German positions on Monte Cassino and helping the Allied ground forces eventually overcome the enemy entrenched along the Gustav Line.

The 332nd Arrives

In early February 1944, Davis and the 332nd had left Michigan and sailed for Italy, where they were assigned to the Twelfth U.S. Air Force. The 332nd was based at Ramitelli Airfield, north of Foggia on the Adriatic coast of Italy, above the “spur” of the Italian “boot.” There they would be joined by the 99th.

Upon arrival, the 332nd initially flew obsolescent Bell P-39 Airacobras that were too slow to chase German fighters, so the group was assigned to escort convoys, protect harbors, and fly armed reconnaissance missions. They would soon get better planes—Republic P-47 “Thunderbolts”—and then, in June 1944, P-51 Mustangs.

The Tuskegee Airmen worked closely with an all-white unit, the 79th Fighter Group. The Black pilots patrolled the air over the Anzio beachhead to provide cover for the Allied ships. Over a two-day period, flying a dozen P-40 fighters led by Captain Clarence Jamison, the 99th Fighter Squadron and 332nd Fighter Group shot down 12 enemy planes that were in route to attack Allied shipping.

The endless training and waiting had finally paid off as critics and skeptics suddenly changed their tune. The same Time magazine that published the report critical of the men, now wrote that “any outfit would have been proud of the record…. These victories stamped the final seal of combat excellence on one of the most controversial units in the Army, the all-Negro 99th Fighter Squadron.”

New Mission: Germany

The P-47 didn’t have the range for deep missions from Italy into Germany, which allowed German fighters to feast on the bombers as they made their runs. Davis was summoned to meet with General Nathan F. Twining, the commander of the Fifteenth Air Force.

Twining needed fighter escorts for his bombers, so he agreed to equip the men with P-51 Mustangs, which could fly roughly twice as far at the Thunderbolt, easily making it into Germany and back.

By the end of June, the 332nd began getting the new P-51 Mustang fighter, the best fighter in the American arsenal. It flew faster than the P-47s but was not as durable; however, it was decisive in the air war over Europe. The P-51 soon became a favorite of the pilots with its ability to maneuver and use its speed to evade and attack the enemy. Not satisfied with the color of the tails of the planes, the ground crews painted the tails red; hence the term “Red Tails” became associated with the 332nd.

Davis’s 332nd Fighter Group started escorting heavy bombers into Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Germany. The 332nd was a force to be reckoned with, racking up more kills on escort missions with a low bomber loss. They even managed to sink a German destroyer in the Adriatic Sea. The honors for this went to Captain Wendell Pruitt and Lieutenant Gwynee Pierson.

In a 2019 interview in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Lieutenant Harold H. Brown of Minneapolis told a reporter, “You join up [with the bombers], fly your mission, eager beaver, you were hoping that you would run into enemy aircraft. We always used to say: If enemy aircraft come up, that’s ‘DFC Day,’ Distinguished Flying Cross Day. We’re going to get some victories.”

While on low-level, ground-support strafing missions, things would get a little hairy. “You know there’s a risk involved, but that’s in the back of your mind,” Brown said. “You’re strafing ground targets, blowing up locomotives and all the rest of it, and it isn’t that you enjoy doing it, but you’re doing your job.”

Brown said the pilots were aware of the risks but ignored them. “We generally thought we were invincible. ‘No, they’ll never shoot me down—I can out-fly any of them.’ ”

The Tuskegee Airmen’s training and experience made good use of the Mustangs, which proved to be a game changer in the air war of Europe. Lieutenant Clarence “Lucky” Lester downed three German fighters over Italy in six minutes on July 18, 1944.

He reported, “I saw a formation of Messerschmitt Bf 109s straight ahead, but slightly lower; I closed to about 200 feet and started to fire. Smoke began to pour out of the 109 and the aircraft exploded. I was going so fast I was sure I would hit some of the debris from the explosion, but luckily I didn’t.

“As I was dodging pieces of aircraft, I saw another 109 to my right, all alone on a heading 90 degrees to mine, but at the same altitude. I turned onto his tail and closed to about 200 feet while firing. His aircraft started to smoke and almost stopped.

“My closure was so fast I began to overtake him. When I overran him, I looked down to see the enemy pilot emerge from his burning aircraft. I remember seeing his blonde hair as he bailed out at approximately 8,000 feet. By this time I was alone and looking for my flight mates when I spotted the third 109 flying very low, about 1,000 feet off the ground. I dove to the right of him and opened fire…. As I did a diving turn, I saw the 109 go straight into the ground.”

Tangling With Jets Over Germany

On March 24, 1945, over three dozen P-51s, led by Colonel Davis, escorted B-17s deep into Germany to attack the Daimler-Benz tank factory in Berlin. There, in addition to the Fw 190s, they encountered some rocket-powered jets: the Me 262s. This was the first time in history that a jet was used in aerial combat, but that did not faze the skilled pilots of the 332nd.

During that March 1945 mission over Germany, Lieutenant Harold H. Brown, in a P-51C, got on the tail of one of the Me 262s. He followed the jet down to tree-top level but an anti-aircraft battery disabled his P-51 and forced him to parachute to safety.

As he floated to earth, he was surrounded by angry German civilians with a rope who seemed ready to lynch him. A German policeman intervened and transported him to a multinational POW camp, where a popular joke among the captured Tuskegee aviators was that the prison was the first time they had experienced integration. (Brown was one of 32 Tuskegee Airmen to be captured during the war.)

After the war, Brown stayed in the Air Force, served in Korea, then attended Ohio State University and earned a doctorate in education. In 2017, his book, Keep Your Airspeed Up, was published.

As Daniel L. Haulman wrote in his 2015 monograph “Tuskegee Airman Chronology,” that “the total number of escorted bombers shot down was significantly less than the average number of bombers lost by the six other fighter escort groups of the Fifteenth Air Force.

“On the longest fighter-escort mission from Italy, on March 24, 1945, to Berlin, three Tuskegee Airmen each shot down a German jet aircraft that could fly significantly faster than their own red-tailed P-51 Mustangs. When the 332nd Fighter Group returned from Italy, it had proven that black fighter pilots could fly advanced aircraft in combat as well as their white compatriots or their enemies.”

The Me 262 was faster than anything the Allies had in their arsenals, but the Tuskegee Airmen fought them tenaciously. In spite of their speed (maximum 540 mph), the German jets were easy pickings for pilots Charles Brantley, Earl Lane, and Roscoe Brown.

In an official report, 1st Lt. Roscoe Brown described how he downed one: “I pulled up at him in a 15 degree climb and fired three long bursts at him from 2,000 feet at 8 o’clock to him. Almost immediately, the pilot bailed out from 24,500 feet. I saw flames burst from the jet orifices of the enemy aircraft. The attack on the (U.S.) bombers was ineffective because of the prompt action of my flight in breaking up the attack.”

As Roscoe Brown (who was valedictorian of his 1943 graduating class at Springfield College in Massachusetts) would describe years later in an interview, “We knew the German jets were faster than we were. Instead of going directly after them, we went away from them and then turned into their blind spots.”

Impressive Record

The Tuskegee Airmens’ performance in World War II was impressive. The 332nd earned 96 Distinguished Unit Citations. They criss-crossed all over central and southern Europe during the course of the war, wreaking havoc on the Luftwaffe planes and pilots they encountered.

They put to bed any idea of the inferiority of African Americans’ ability to serve with distinction and perform tough combat assignments. Nearly 1,000 men trained in the Tuskegee pilot-training program from 1941-46. Of the 355 men deployed overseas, 84 paid the ultimate sacrifice, 68 in combat. A total of 2,845 missions were flown for the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces.

Their bomber-escort record is nothing short of exemplary. Of their 179 bomber-escort missions, they only lost bombers on seven missions, for a total of 27, compared to the average of 46 for other fighter groups. This dispels the popular myth that they never lost a bomber, but their record stood out, and bomber crews began to request that the Red Tails escort them. They destroyed 112 enemy planes in the air and 150 on the ground while damaging 148 others; 950 rail cars and trucks were destroyed, along with 40 boats and barges.

The pilots of the Tuskegee Airmen were some of the best ever produced by the U.S. Fighting the twin enemies of racism and the Nazi foe, they had the motivation and drive to prove their skeptics and doubters wrong. Enduring many months of waiting and training, their skills were refined and sharpened.

Facing a well-trained and clever enemy, the Tuskegee Airmen entered the war at a crucial time when the air war over Europe was still very much in doubt, with American bombers taking unacceptable losses. These brave men helped to reverse that tide. In short, they helped this nation win that war.

The Struggle Goes On

Unlike today, the Tuskegee Airmen did not immediately receive the recognition from white America that they deserved for their exemplary record during the war and the immediate years following it. There were no parades like those that welcomed the return of many white units. It was the Black press, their friends, and family that kept their stories alive. They returned home to a segregated America, the very thing that they and Black servicemen hoped would have changed.

But it didn’t. The highest scoring Tuskegee Airman from the war, Captain Lee Archer, with four victories to his credit, was refused service in a railroad dining car with his wife, while traveling to his next military assignment. Therefore, he and many of these men and Black veterans overall were active in the civil rights movement that followed the war.

Amongst themselves, they formed an organization called Tuskegee Airmen Inc. to keep their legacy alive. It was not until 40 years after World War II that a movie was made about them via HBO.

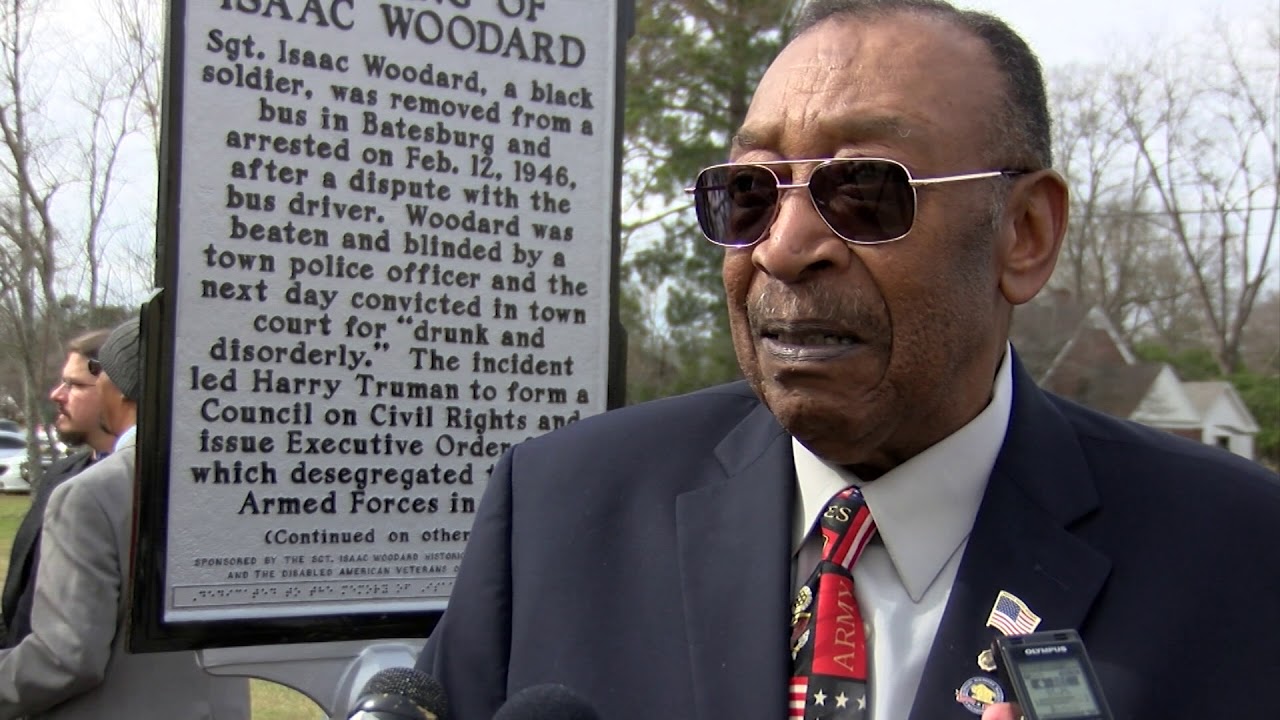

The performance of African Americans in the war and in particular the performance of the Tuskegee Airmen was influential in President Truman’s decision in signing Executive Order 9981 in 1948 to desegregate the military. This, coupled with the well-publicized violence against African American veterans in the South such as Isaac Woodard (who was beaten by South Carolina police and left permanently blind just hours after he was honorably discharged from the Army), and political pressures forced President Truman’s hand.

In another example, a recent Atlantic magazine article said, “Sadly, the Tuskegee Airmen continued to experience racism, even after their heroic exploits in the skies over Germany. Some 160 pilots were arrested and three Tuskegee pilots were court-martialed for walking into an officer’s club at Freeman Field, Indiana, in 1945, despite a direct order from Washington that all pilots, regardless of race, were to be given access to the club.

“The records of the pilots were not cleared until 1995, even though the ‘Freeman Field Mutiny,’ as it was called, was considered a critical step in the Civil Rights Movement and the integration of the armed services.”

Civil rights leaders such as A. Phillip Randolph warned the president and Congress that African Americans would resist any future military draft that would perpetuate segregation, determined to pressure the federal government to integrate the military, continuing the work he started during the war with his threatened march on Washington.

The desegregation of the military took place six years before the famous Brown vs. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court that banned segregated schooling, and 16 years before federal law banned segregation nationwide in all areas of public life.

Going to war with a segregated armed forces harmed the opportunities of African Americans and was inefficient logistically to maintain duplicate service units, but the military did provide opportunities after the war that were not available to African Americans in the civilian world.

By 1949, the Air Force had deactivated all-Black flying units, allowing white and Black pilots to train together.

Despite being snubbed by the white mainstream press, Hollywood, and popular culture for decades, the postwar years in the military were good for the careers of many of the Tuskegee Airmen. Quite a few stayed in the service and served with distinction in the Korean and Vietnam wars as high-ranking officers.

The first Black Air Force generals and squadron commanders were Tuskegee Airmen. Others went on to achieve advanced degrees and had rewarding careers in science, engineering and academia. In 2007, they were collectively awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush. In 2009, they were invited to the inauguration of President Barack Obama.

As for Ashley, Brown, and McGee, they continued to serve their country as they went on to greater rank and honors. After the war, Willie Ashley Jr. returned home and continued to serve in the Air Force Reserves, earned masters and doctorate degrees, retired as a lieutenant colonel, served in the U.S. government, and taught at Howard University. Retiring with the rank of lieutenant colonel, Ashley was buried with honors at Arlington National cemetery in 1984.

Harold H. Brown went on to serve his country in the Air Force for an additional 20 years, retiring as a lieutenant colonel in 1965. Brown would later earn his Phd. and serve in higher education. As of this writing, he was still alive.

After World War II, Charles McGee flew missions in Korea and Vietnam, totaling 409 combat missions. A recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, and later the Congressional Gold Medal, he escorted B-24 Liberators and B-17’s Fortresses over Germany, Austria, and the Balkans. In 2020, he was promoted from colonel to brigadier general. He died in January 2022 at the age of 102.

To this day, the Tuskegee Airmen continue to be honored and recognized for their service in public appearances, books, magazines, documentaries, and in numerous publications. Finally, a grateful nation was catching up to what these men knew about themselves the moment they stepped into a cockpit.

Today, Americans look back in shame at how these men were treated at a time when the nation needed every able-bodied man and woman to do their part for the war effort. Yet, Americans can feel pride at how these men never gave up the drive to achieve their goals and earn the respect and gratitude of their countrymen.

The story of the Tuskegee Airmen is a story of perseverance through adversity. Despite the obstacles thrown their way, racist policies, and outdated and insulting pre-war thinking, they proved the skeptics wrong. It is what makes their story timeless—a story that continues to inspire new generations of Americans to achieve greatness.”

Dante Brizill has been a Social Studies educator and speaker for the past 19 years in Maryland and Delaware. He is the author of the Greatness Under Fire series available on Amazon. He resides in Townsend, Delaware.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments