By Walt Larimore and Mike Yorkey

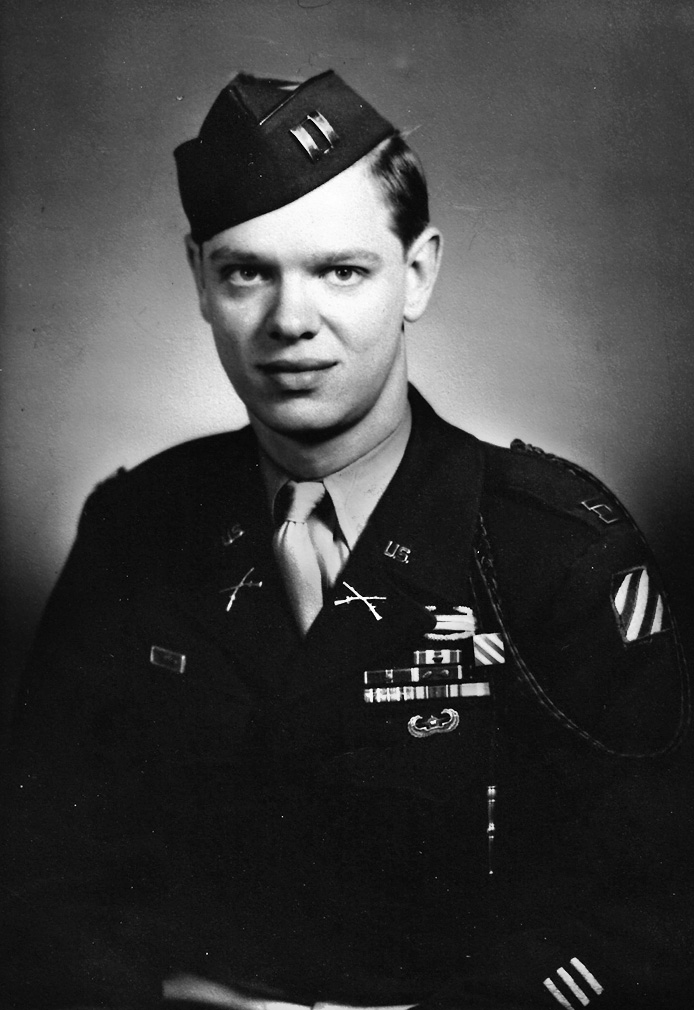

During World War II, the U.S. Army determined that the typical frontline infantryman couldn’t take much more than 200 to 240 days of combat before mentally falling apart. By April 1945, 1st Lt. Philip B. Larimore, Jr., of the 3rd Infantry Division’s 30th Infantry Regiment, had already trudged through 416 days of frontline combat, and he wondered if he was fighting on borrowed time.

After landing in Naples, Italy, in late February 1944, Phil had led his Ammunition & Pioneer Platoon through the Anzio “Bitch-Head,” marched into a liberated Rome, and participated in Operation Dragoon, the amphibious assault on southern France that began on August 15, 1944.

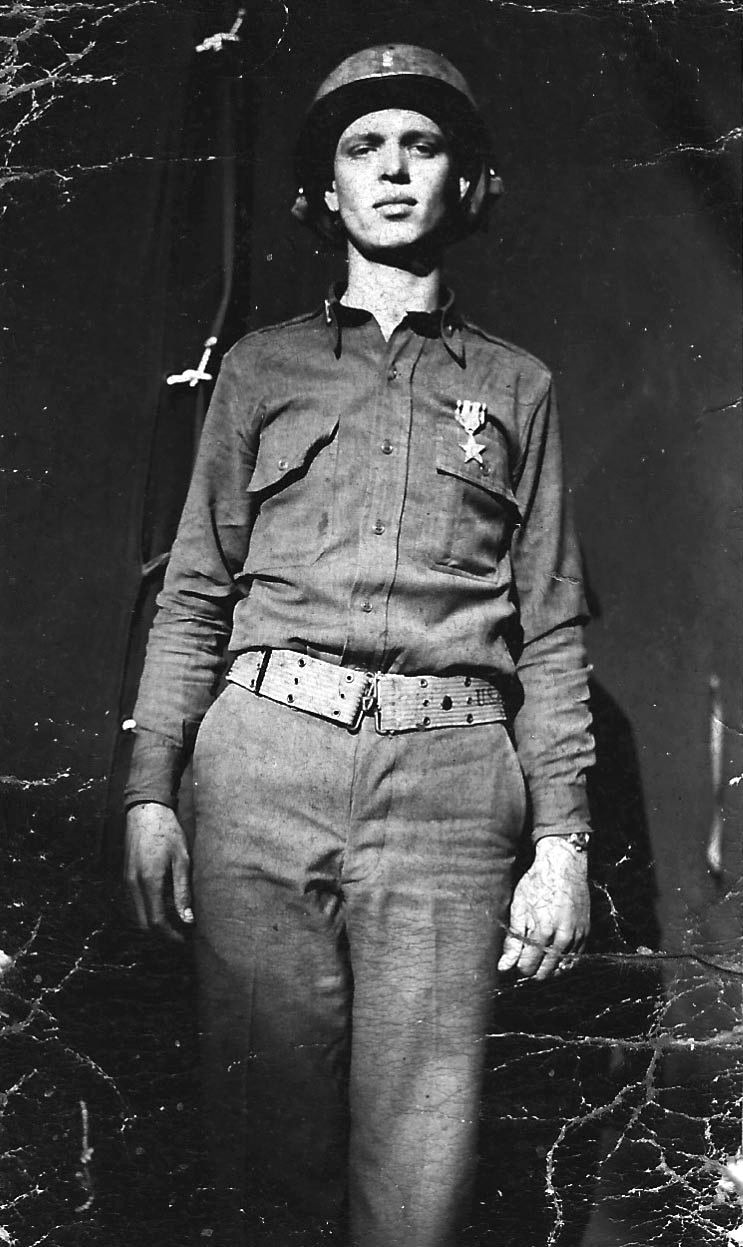

In the fall of 1944, Phil took a sniper bullet to the right hip in a ferocious battle with the German Wehrmacht outside St. Diè in northeastern France—his second major wound in the war. He was lucky to be alive. He recovered in an officer’s ward next to Audie Murphy, another 3rd Division dogface and the most decorated American combat soldier of World War II. Murphy was to receive every military combat award for valor available from the U.S. Army, while Phil would be awarded most of them.

Phil returned to active duty on Christmas Eve 1944 and participated in intense firefights on the frozen Colmar plains, almost being overrun by elite German troops in the near-disaster of the Battle for the Maison Rouge Bridge. He was promoted, becoming one of the youngest company commanders in the war. The Allies crossed the Rhine River with the goal of beating the Russians to Berlin.

In the first days of April 1945, Phil completed a top-secret, one-day mission into Czechoslovakia, far behind enemy lines, to confirm Hitler’s secret horse farm, which housed most of the breeding population of the world-famous and critically endangered Lipizzan horses—all later rescued by U.S. Army forces in the secret and potentially illegal Operation Cowboy.

Phil was proud to return to the “Rock of the Marne” 3rd Infantry Division, which was awarded one-fourth of all the Medals of Honor presented during the war and suffered more casualties than any other division in the U.S. Army—over 34,000 altogether—with over 80 percent being riflemen. More than 80 percent of officers killed were front-line first or second lieutenants. It was the only infantry division in WWII to receive the Distinguished Unit Citation.

After returning to his unit, Love Company, part of the 30th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion, they met heavy resistance entering the town of Wolfsmünster, Germany—between Frankfurt-am-Main, to the west, and Nuremberg, to the southeast. When a sniper shot one of Phil’s officers through the head, instantly killing him, he and his executive officer, Abe Fitterman, ran up and found their men crouched behind a downtown building. The officer’s body was lying in the middle of the street; what was left of his head rested in a pool of blood.

“Helluva sniper,” the sergeant warned them. “He can shoot a fly off the top of your helmet. We think he’s shooting from the town square—maybe an office building or the church. About 250, 300 yards up the road. Want to call in artillery?”

Phil took off his helmet, leaned over his sergeant, who was kneeling, and slowly pushed his helmet around the corner. He was not surprised when the helmet was cracked out of his hand by a sniper bullet.

“Damn! He is good!” Then again, Phil knew that most German snipers were accurate up to 400 yards.

“German sniper rifles have a five-round internal box magazine, right?” Abe asked.

“Haven’t seen one with more,” Phil answered. “Yet.”

“If he didn’t reload, and I doubt he did, he’s got four shots left.”

Abe came around Phil and crouched down behind him and the kneeling sergeant. “I’ve got an idea, Lieutenant.”

“I’m all ears.”

“You guys each have a 15-round magazine in your Carbines?”

Phil and the sergeant nodded.

“Sergeant, you take the low position. Phil, you take high. On my signal, aim your rifles around the building and begin rapid fire toward the church, but don’t expose any body parts and only release six or seven shots.”

“What do you have in mind?” Phil asked.

“After he shoots back, I’m going to sprint across the street and see if I can get a bead on the guy. I ought to have a better angle from over there. Cover me by blasting out the rest of your magazines.”

Phil remembered the “three-second rule” that one of his A&P platoon sergeants taught him at Anzio, where the men had been pinned down for over four months. If an enemy soldier drew a bead on you during a firefight, it took him three-fourths of a second to locate you. Then it took him another second and a half to raise his weapon and another half a second to put you in his sights. Three seconds was all you had to get cover.

Phil nodded and moved into position alongside his sergeant, their rifles poised.

“On the count of three,” Abe instructed. “One-two-three!”

Phil and the sergeant began firing blindly. Within seconds, three or four sniper bullets blasted the corner of the brick building, spraying fragments over the men, who pulled their guns back. A second later, Abe hotfooted it to the other side of the street without drawing a shot.

The three-second rule, Phil thought, happy that Abe had just enough time to sprint across the narrow road.

Then Abe pulled a hand mirror out of his belt pack. “On my signal, do the helmet trick again.”

“Damn, Abe! We’re gonna run out of helmets before the bastard runs out of ammo!”

Abe smiled as he lay on the ground, positioning the mirror around the edge of the building so he could examine the street. Several blocks away, on the other side of the town square, sat an ancient stone church with a rectangular stone steeple and a stone balcony around it.

“Okay!” he yelled. “Now!”

The sniper took the bait and easily nailed the sergeant’s helmet, allowing Fitterman to see the muzzle flash.

“He’s in the top of the church steeple. About three blocks up.”

“I’ll call in two bazooka squads and a tank to come up pronto,” Phil said.

Within a matter of minutes, all arrived. Phil signaled the tank to go around the corner and take out the steeple.

Machine-gun, rifle, and small-arms fire erupted from buildings on either side of the street, ricocheting off the tank’s front and turret. Phil knew the sniper would not fire on the tank and give away his position.

The Sherman moved up to—but not over—the officer’s body. The tank barrel slowly raised. Phil smiled as he realized the sniper now knew he’d been found out. Probably crapping in his pants and jumping down the steps as fast as possible, Phil thought. But we’re gonna nail his ass!

With a single blast from the tank’s 76-mm cannon, the steeple disintegrated. Fragments of lumber and limestone rained onto the town center. As if in slow motion, Phil watched the sniper tumble through the air until the lifeless body thudded onto the cobblestones.

Phil had the tank provide cover while he ordered one bazooka team and half his men to cross the street quickly. By the time they reached the town square, where all resistance had ended, the men had killed five, wounded 11, and captured 125 German soldiers.

As they walked into the town square, Abe checked out the dead sniper. He was rolling the corpse over when Phil walked up.

“Well, I’ll be!” Phil exclaimed as he and the men gathered around. At their feet was a young and attractive woman dressed in civilian clothes. The GIs had seen increasing numbers of civilian snipers, but this was the first German female fighter any of the men had seen.

“Why the hell didn’t she shoot and scoot?” Abe asked.

“Maybe an SS mistress?” wondered one. “No matter. Her sorry ass is dead.”

“Let’s move out!” Phil barked.

Throughout the night, the regiment advanced east and northeast, taking all assigned objectives en route, inflicting severe damage to enemy equipment and taking many more POWs.

The following day, April 6, 1945, a cobalt-blue sky couldn’t decide whether to issue sprinkles or deliver a dousing rain shower.

Love Company joined Item Company in clearing several villages before moving out toward the east. Their goal for the day: the village of Oberthulba. That morning, they passed upturned and bombed-out enemy vehicles with dead drivers and crew scattered about, the result of sweeping strikes from P-47 Thunderbolts that strafed and bombed the German column to oblivion. Phil watched impassively as two gray-haired civilian men struggled to lift and toss the stiffening corpses onto a horse-drawn wagon.

Phil studied his map, which showed pastureland bordered by thick forests on each side. He assigned his 1st Platoon to penetrate the forest to the north and his 3rd Platoon to the south. His 2nd Platoon, trailed by tanks and tank destroyers (TDs), would stay with him and follow a single-lane road slicing through green pastureland. From his vantage point, he observed flanking riflemen working their way slowly through thick underbrush and woods. The platoons stayed in touch with him by radio but encountered no resistance.

Phil was apprehensive that they might be walking into a trap—and wished his command had given him time to send scouting patrols up front. As the men moved out of the woods, however, an enormous eruption of small-arms and machine-gun fire burst out from the woods directly ahead.

The GIs instinctively hit the ground and returned fire. A tsunami of bullets whistled overhead and was so concentrated that Phil couldn’t initially differentiate between friendly and enemy fire. He motioned to Fitterman and the rest of his Command Post (CP) staff to follow him as he moved them up and into a gully.

Then the enemy fire suddenly stopped. Only an occasional rifle shot could be heard. He called the platoon leaders to determine what was happening.

“Hit a thick line of Krauts,” answered one of his lieutenants. “Damnedest thing. Looks like a company made up of young boys and old men.”

“I don’t care what their ages are. We gotta take them out,” Phil said.

Yelling to one of the radiomen, he issued an order: “Call battalion. Get the A&P platoon up here pronto with as much M1 and BAR ammo as they can carry.” Next, he radioed his up-front men and found out that both platoons had taken a few casualties but were intact and ready for orders.

“Ammo’s coming up,” Phil said. “We need to advance immediately, before those bastards have time to reach the protection of Oberthulba. What about moving forward with marching fire?” he asked.

Phil had trained his men to use their M1s, BARs, and even machine guns while employing marching fire. Infantrymen kept the butt of their rifles halfway between their belts and their right armpits, shooting one round every two to three steps. For machine-gun units, one man carried and fired the heavy gun while another walked alongside him with the ammo belt.

“Hell, yes, we can do that,” his lieutenant answered.

“When mortar fire and tanks start firing over your heads, that’s your go signal.”

“Roger.”

On Phil’s command, the mortars began their fire, followed by powerful fusillades from the tank and TD machine guns. As their tracers lit up the air, the riflemen separated into one long skirmish line. After a minute or two of fierce covering fire, Phil gave the attack order. The men rose in unison and walked forward with an unremitting march of fire.

“Damn!” Phil exclaimed as he watched the action through his field binoculars, “What a beautiful thing.”

Together, he and Fitterman saw virtually no return fire as the infantrymen moved quickly up to and into the forest that had been shredded by the covering fire.

Radio reports streamed back to Phil. No casualties on the American side, but many enemy soldiers were killed or giving up. The rest were racing to Oberthulba, where they could regroup and reorganize.

Phil jumped into a company jeep, followed by Fitterman. Up ahead was Oberthulba, a quaint farming village of a couple thousand people, smack dab in the middle of Germany.

Phil and Abe drew up a quick battle plan for a three-platoon frontal attack. The time was four o’clock in the afternoon. Phil relayed the news to his subordinates that if the attack went well, then they would billet inside a lovely home in Oberthulba that night.

Phil knew the idea of a hot bath and a soft bed would keep his men motivated and morale high for one more day. War was a day-by-day proposition, wasn’t it?

Approaching Oberthulba, Phil had three Shermans and TDs at his disposal, one for each platoon. Using the tanks as cover, the three platoon leaders set up machine-gun nests in shallow ditches.

As the platoons began to move forward, significant fire came from enemy machine guns in the forests on both sides of the village. Phil’s tanks and heavy machine gunners quickly silenced them.

Phil’s flanking platoons used their BARs and light machine guns to lay down suppressing fire along the forest edge. Then he looked at his watch. In two minutes, a 10-minute-long artillery barrage would commence, and the shelling aimed at the town center would give him and his men a distinct advantage. He called the timing to his platoon leaders and heard the roar of tanks as they prepared to move forward with the infantrymen advancing behind them.

“Do not move forward until 1708 hours, two minutes before the artillery ends,” Phil barked into the radio handset. The goal was for the men and tanks to hit the edge of town just as the barrage ended.

Precisely on time, at 1700 hours—5:00 p.m.—the preparatory barrage began. Like all front-line men, Phil loved the sound of artillery—as long as it was his own. Wave after wave of shells whistled overhead, as if taking flight from the forest directly behind them, sailing over the treetops and the advancing men, and pouring into the town in one roaring explosion after another. A cacophony of smaller eruptions from 81mm mortars joined in the fiery mayhem. Then an unusual and unexpected surprise descended upon the Germans.

A half dozen shiny P-47 Thunderbolts emerged from the skies, the setting sun’s rays reflected on their silver bodies and wings. They swooped down over the village and unleashed their .50-caliber machine guns while raining down more bombs. In a few short minutes, the combination of artillery and air firepower had turned Oberthulba into a fiery inferno.

The P-47s roared back up into the sky, each steeply banking, and then returned for a second strafing run with their machine guns and cannons unloading a hailstorm of red-hot lead and explosive shells before disappearing to the west. Meanwhile, artillery continued to whistle overhead and explode in the town.

Two minutes before the artillery was scheduled to stop, Phil radioed out commands to prepare to seize the village. He could see his trained veterans, with scattered but now battle-tested replacements, crouched and ready to spring. Phil wondered how anyone could have survived the thrashing the town had taken, but he knew that the stone buildings contained cellars where the enemy could patiently wait out the barrage.

The tanks began to rev their engines. Phil counted down the seconds: ten, nine, eight …

“Attack!” he yelled into the radio. “All platoons attack!”

He prayed he had the timing right as artillery shells continued to fall. The tanks edged forward with some of the men following behind them. Other soldiers spread out, using marching fire in their approach formation. The tanks, spewing fire, moved slowly enough for the men to keep up. Time almost seemed to stand still. Rounds from the machine guns, punctuated by tracers, once again formed an umbrella of molten lead and steel over the advancing men’s heads.

When the men were within 50 yards of the town’s outer edge, the artillery fire stopped. Beyond thick billows of swirling smoke, orange flames reached into the air from an untold number of burning buildings.

Phil’s chest swelled with pride, and his spirit overflowed with gratitude. The coordination and formations of men, air power, artillery, and armor were textbook-perfect. He hadn’t seen an attack this precise and well-coordinated carried out for the entire war. He wished his superiors were here to see his men perform.

Phil and his CP men, including his XO, began to double-time toward the village center. To his surprise, the main road was littered with dead and dying Germans of every imaginable age—from young teens to older men.

So, this is what the end looks like.

Phil had heard from Colonel Lionel C. McGarr, the commander of the 30th Infantry Regiment, that the German High Command had ordered fanatical “last man” stands at every town to give the Nazis more time to prepare defenses in larger cities. The Germans were sending their least effective soldiers—the very old and very young, known as the Volkssturm—to the front lines, no doubt saving their best troops for the very end.

As Phil entered the main road into the burning village at 5:30, he spotted his men herding a parade of around 100 dazed and shocked German soldiers to the rear, their hands clasped behind their heads. Many were wounded and bleeding. All seemed stunned and confused. As Phil and Abe moved down the street, his men were shoving other German prisoners out of buildings on either side of the road. The German soldiers looked terrified as the GIs shouted commands and pushed them forward with the tips of their rifle barrels.

The enlisted prisoners were generally easy to handle, but Phil knew that it was the officers he had to watch out for, especially those who were part of the SS, the military branch of the Nazi Party’s organization. There were stories about SS officers shooting fellow German soldiers who waved white flags, advanced toward the Allied lines with their hands up, or surrendered. Maybe that’s why these prisoners looked so nervous.

Phil recalled how just a week earlier, in the center of one small German town, one of his men had brought out an older man, a German civilian, in a crumpled suit, carrying a small white handkerchief that he waved over his head. “He’s the mayor,” the private explained. “Here to surrender.”

The town mayor kept looking nervously over his shoulder, which aroused Phil’s instincts. He put his hand on his holstered Colt .45, unlatched the holster flap, lifted the gun slightly, and clicked off the safety. At that moment, an SS officer stepped out of the shadows with his 9mm Luger drawn.

The German SS soldier shot the old man in the head, to everyone’s shock. Then he immediately swerved to fire at Phil when Phil rapidly fired twice. The SS man’s forehead and chest exploded as he was blown backward, dead before he hit the pavement. Phil’s men were not surprised; they had seen his expert marksmanship many times.

In Oberthulba, four SS officers were shoved out of a building and onto the street by several GIs. Suddenly, an SS officer lunged at one of his men’s rifles. The GI hit the German in the shoulder with the steel butt plate of his Garand, knocking him to the ground.

Like an angry bull, the frenzied SS officer leaped off the ground and attacked. The GI hit him again in the head with the butt plate, sending him reeling to the cobblestoned street a second time. The SS officer, dazed and bloody, slowly pulled himself to his knees and then charged again.

This time the German soldier was struck so hard in the head that he never got up.

“Damn,” Abe Fitterman muttered to Phil. “SS officers are unpredictable SOBs.”

That evening, after everything was buttoned up in Oberthulba, Phil was hoping for orders to find a CP and billet for the night, but it was not to be. The men were ordered to keep moving. Three miles further east, the company arrived just outside the town of Albertshausen at midnight, where they were met by light enemy resistance. By 2:25 a.m. on the morning of April 7, Love Company had taken and cleared the town. The men’s morale was excellent. It had been, by all counts, a perfect day.

Phil made sure his men were billeted in the best houses in town. Residents were awakened with a loud knock and were told they had fünf minuten—five minutes—to leave. Following one family’s hasty departure, Phil and his men entered the home, where one of the men started a fire in the living room fireplace. Smoke began to fill the room. Turned out the chimney wasn’t drawing.

After opening the damper and clearing the air, one of his men investigated and found the chimney flue stuffed with smoked hams and sausages that the family had tried to hide. The banquet was shared with several houses. With full tummies, the GIs luxuriated with hot showers and slept in duvet-covered beds with thick, soft mattresses.

For some reason, though, Phil couldn’t sleep, even though he was pleased most of his men were inside a warm home with a full stomach and a comfortable bed. He spent time visiting each of the sentries and men in the outposts.

He loved leading his company, loved his guys, and admired the tenacity they were showing in the last stages of a long war; but now that victory was in sight, he just wanted the fighting to be over and go home.

At 1:15 p.m. on April 7, Phil received an unusual radio call from one of his platoon leaders, Lieutenant Emil T. Byke, who was leading a reconnaissance patrol outside the town of Bad Kissingen, a world-famed spa before the war.

Byke began, “One of my squad leaders reported a vehicle just outside Bad Kissingen, displaying a white flag. I went to verify the report and found three German military personnel in the vehicle. I approached the Germans with coverage all around and was greeted by two German officers who, in broken English, asked if I would go into the town of Bad Kissingen with them and meet their commander. They want to surrender.”

“Were the officers SS?” Phil asked. The memories of what had happened in Oberthulba the day before were fresh in his mind.

“Nope.”

“Permission granted. Just be sure to take a well-armed jeep or two with you.”

“Yes, sir.”

Byke radioed back an hour later. “Phil, the damnedest thing just happened.”

“What?”

“When we arrived in Bad Kissingen, we were met by a German soldier who couldn’t have been more than 14 years old. He was carrying a white flag and spoke excellent English. We followed him to the town square, which was filled with German soldiers who had stacked their arms in piles before us. Two bodies were hanging from the city hall balcony. They were two local officials who wanted to surrender. SS troopers had hung them as traitors.”

“Are the SS guys still around?” Phil asked.

“Flew the coop,” Byke replied. “The German officers presented me to their commander. Through the kid, this commander told me that he wished to surrender and wants me to convey the message up the ladder. I agreed to do that, but before we departed, he took us to a nearby hospital.

“We found a bunch of our wounded GIs in a German military hospital. They were all crying with joy at seeing us. Some of the boys hugged me and wanted to know if they were going home. I told them that we were at the gates of the city and that I would return as fast as possible.”

“Good work, Byke,” Phil said.

Phil radioed battalion and was put in touch with Lt. Col. James E. Chaney, the battalion commander. After relaying the news, Chaney told Phil to meet him outside of town at Byke’s jeep.

When Phil and Abe arrived, they found Lieutenant Byke had placed his men at advantageous points on the hills surrounding Bad Kissingen. At the same time, Company M, commanded by 1st Lt. Harold J. Saine, had brought up mortars and placed them in firing position “just in case.” He then sent two squads inside the city for reconnaissance.

Just then, Colonel Chaney’s jeep screeched to a halt. Phil and Byke updated him on the latest developments. It was looking like they could safely meet the German commander in the town center to discuss terms of the surrender. With two squads of riflemen providing protection, they slowly drove their jeeps into the resort town, encountering no hostile fire. Their delegation was met at the center of town in front of city hall, where a German general and his command officers were waiting for their arrival. All were unarmed.

After handshakes, they sat down in an office. The first question Colonel Chaney asked was this: “Do you understand what unconditional surrender is?”

The reply from the German side was affirmative.

“As you know,” Chaney continued, “Bad Kissingen is an important rail and highway center. Because its spacious buildings can easily accommodate thousands of troops, Bad Kissingen is a highly desirable military prize. I must emphasize that the 3rd Division will not accept Bad Kissingen as an ‘open city,’ however. It will be used as a military base for United States troops. Is that acceptable?”

As if you have a choice, buster, Phil thought.

The general nodded his approval, and that was that.

After the surrender, Phil, Abe, and several of their men walked around the town, rifles slung over their shoulders. They came across a factory that manufactured dress suits. They went inside the factory, where they took turns putting on high hats and bow ties with their dirty uniforms, laughing at the incongruous look.

There were also bolts and bolts of silk fabric—white, shiny, and smooth to the touch. The men didn’t have the foggiest idea why the Germans were still making such finery in time of war. The men cut off pieces of the satiny fabric to make handsome scarves, which they draped around their necks and under their collars, giving a regal appearance.

For a fleeting moment, the war was forgotten.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion rounded up German prisoners in Bad Kissingen, capturing 2,825 that day, a record for the division. That night, the Regimental CP set up in a beautiful hotel just on the outskirts of town. When Colonel McGarr arrived, he made the men wipe their feet before they walked into the marble-floored lobby.

Phil and his men stayed in a ritzy hotel in the center of town that night. After placing guards and outposts, the men were served a hot meal, received clean clothes, and were handed their mail. Most of the men were nearly giddy with the opportunity to read letters and enjoy some decent food. For the second night in a row, they slept on mattresses.

The Love Company officers enjoyed a nightcap and cigars together, dog-tired but proud of the battles and victories of the three previous days. In many ways, everything had gone perfectly.

Abe blew a ring of smoke and looked at Phil. “I can feel it in my bones,” he said. “This damn war is almost over.”

“Hope you’re right, Abe,” Phil said softly. “Hope you’re right.”

As Phil and his men slept, Colonel McGarr received orders just after midnight that jump-off was scheduled for 7:30 a.m. the next morning, April 8. An intelligence officer, however, warned McGarr that his troops had better be prepared to enter a long-predicted buzzsaw as they continued their easterly advance. American forces could expect to meet considerable artillery and anti-tank fire and even more fanatical infantry.

Phil and his command officers were awakened at 3:00 a.m. to receive their orders and prepare for a difficult day. During the briefing, the men were told that the Germans could be expected to try, once again, to slow the 3rd Division’s relentless attack, most likely to give the Nazi “bigwigs” a chance to withdraw to the rumored “National Redoubt” area in the Bavarian Alps.

What lay ahead for Phil was a day he would never forget.

On the morning of April 8, 1945, Phil and Love Company jumped off from Bad Kissingen at 7:30 with King Company on their right flank. Passing through pastureland bordered by forests, they reached several successive objectives with minimal resistance, overcoming a small firefight at 9:50 a.m. and another at 10:05, followed by defeating Germans at three log roadblocks and bypassing another two.

Several of the skirmishes involved hand-to-hand fighting to the death—in this case, resulting in all German deaths. Phil had to take out a German officer at point-blank range when he tried to draw his Luger in the process of surrendering. The pistol never left the German’s holster before he crashed to the ground, killed instantly by Phil’s quick-draw response.

By 1:30, both lead companies began encountering significant machine-gun and small-arms fire from forested areas bordering their zone of advance. Phil hated hearing the guttural blasts from the German Schmeisser MP 40 (Maschinenpistole 40) machine guns that GIs called “burp guns.” After 15 months of nonstop fighting, he detested the fact that Schmeissers fired at twice the rate of their best American-made counterparts, giving the Germans a battlefield advantage.

Phil called in heavy artillery time and time again, which stalled progress—a development that neither his officers nor NCOs liked. At 6 p.m., they found themselves moving slowly through a wooded section outside the tiny village of Rotterhausen.

As the light began to fade, Phil’s company made a flanking move through the dense thicket of trees. They slowed their advance and moved carefully. Phil found the silence of the woods unnerving. The tension was sky-high among his men—higher than any time in the last three days. None of Phil’s soldiers wanted to be the last to die in this war.

These were desperate times for the enemy. Intelligence indicated that trigger-happy Germans were infesting the countryside, especially in forested areas, setting up traps and ambushes. Phil was greatly concerned about a dangerous situation developing. His men crept low, darting from tree to tree, most with fingers on their rifles’ triggers, others hand-signaling man to man.

Death could be lurking anywhere in the forest surrounding them. Snipers could be nestled in towering firs or behind their massive bases. Machine-gun nests might be hidden behind a camouflage of evergreen boughs, prepared to annihilate Phil’s frontline troops in a hailstorm of gunfire. On top of that, one well-hidden artillery piece could fire its rounds into the tree canopy, raining white-hot shrapnel and splintered wood that would rip through flesh. Death lurked in every direction.

Three of Phil’s fast-moving platoons advanced to the south and east as he, Fitterman, and his radioman followed. Phil had his compass in one hand and a field map in the other, continually scanning it with trained eyes and an intuition gained from over a year’s experience fighting Germans. He almost always knew what the Germans were thinking and doing.

Suddenly, Phil saw something he had missed—a small clearing ahead, surrounded by a forest edge that was slightly elevated over a small meadow. He had Fitterman radio the point men to skirt the field and remain in the forest. The woods ahead suddenly crackled with small-arms fire and the deep rasping sounds from the German burp guns.

Damn, he thought. Too late!

Suddenly, his radioman’s backpack SCR-300 sizzled with distress—it was one of his point-squad leaders. “We’ve been ambushed in a glade! There are nine of us and probably 150 Krauts around us. The rest of the platoon behind us is pinned down. We have four wounded. We’re low on ammo. We’re in a clearing. Help needed now, sir!”

“Shit,” Phil whispered to himself, remembering it was one of his least-experienced squads. He could hear German potato-masher grenades exploding, answered by American grenades and machine-gun fire, adding to the pandemonium. Projecting a calmness he didn’t feel, Phil ordered the 1st Platoon on the left flank and the 3rd Platoon on the right to begin an immediate pincer move to save the trapped squad. He also called for a tank. “I need a medium can now!” he bellowed into the radio handset.

As the battle sounds intensified, Phil spread his field map on the ground and studied it with Fitterman and their artillery FO (Forward Observer), who had just come to the front.

“Our trapped squad must be here.” Phil pointed to the northwest edge of the only nearby clearing. Turning to his FO, he said, “I need fire massed on the other side of the clearing.”

He ran his finger along what appeared to be a forest lane on the map. “Abe, you take over the CP staff. When the first tank gets here, I’ll take it to the clearing to get to my guys.”

“I’ll go,” Abe offered. “We need you back here.”

“Nope. This one’s on me, Abe.”

Phil radioed the trapped patrol. “Fire coming in. Ammo is on its way. First and 3rd platoons are pinching toward you now.”

Surprised to hear the rumble of three Sherman tanks behind him instead of the one he’d called for, he radioed his frontline men. “We’ve got three cans here. We’re coming up now!”

The reply was filled with panic. “We’re pinned down with marching fire! We need help fast!”

As the lead Sherman pulled up, Phil yelled, “Abe, I’m hopping a ride on the lead can! Get artillery firing now!”

Before Abe could object, Phil jumped up on the back of the tank with his radioman in tow. Climbing in behind the turret, he had his radioman hand him an intercom handset that was kept in an empty ammunition container on the back of the tank and stretch the long cord up to him. That would allow him to communicate with the tank commander inside as he signaled to his radioman to hunker down behind him.

As the tank lurched forward, Phil prepared the turret-mounted .50-caliber machine gun, unlocking the safety and cocking it. There was not a lot of ammo, but he hoped it would be enough.

His head snapped up at whistling sounds whizzing overhead. The German MG42 medium machine guns—nicknamed “Hitler’s buzz-saw” by American GIs—continued erupting at 1,000 to 1,200 rounds per minute to his front. His own men’s machine guns gave studied answers at less than half the rate—the American guns sounding like Model Ts compared to the murderous reverberation of the enemy’s heavy automatic firearm.

Approaching the clearing, Phil crouched behind the turret as green tracer bullets from enemy machine guns sliced through the air from the front, while friendly red tracers came from behind on either side of the tank.

“Our guys are 50 yards ahead! Friendly platoons are coming up from behind on our left and right!” Phil called to the tank commander. Into the radio, he yelled, “Second Platoon, send up all three of your squads, pronto! One behind each can as we move up!”

His men sprinted from the forest to the shelter of the tanks, fanning out across the western edge of the clearing, one on his left flank and the other to his right, bullets churning up dirt around them.

“Shermans, move into the clearing!” Phil commanded into the tank handset. He quickly identified three machine-gun nests on the other side of the clearing. The tanks lurched forward as fire poured in, the bullets from multiple snipers missing him by only inches.

Phil ordered the gunners inside the tanks to use their 76mm cannons and .30-caliber machine guns to lay down suppressing fire while he manned the 100-pound, turret-mounted .50-caliber machine gun, firing and taking fire all the way. He sprayed bursts across the forest line, silencing several snipers and destroying at least three machine-gun nests, momentarily quelling the enemy attack.

“I see our guys!” Phil shouted into the SCR-300 handset to the other platoons. “Between the center and left cans! Twenty yards ahead. Let’s get ’em outta here!”

His men emerged from behind the protection of the tanks. As he had trained them, his forward troops laid down a torrent of marching fire as they advanced toward the trapped soldiers, while others ran up and grabbed the wounded. Enemy fire erupted again, and Phil emptied his remaining ammunition, killing several German soldiers and drawing more hostile fire; his squads used the diversion to withdraw.

Out of machine-gun ammunition, Phil jumped off the tank to direct his men, miraculously eluding another hail of bullets, dozens missing him by inches. Suddenly the back of his head took a stunning blow as a sniper’s bullet blew his helmet from his head and knocked him to the ground. Phil, seeing stars, was momentarily stunned.

As if on autopilot, his eyes quickly scanned the trees as he swung his M1 in the direction of the enemy. Spotting a solitary German sniper in a tree, he took aim and triggered several rounds. The sniper’s head exploded, and his body crashed to the earth.

“Got the sonofabitch!” Phil screamed.

His radioman jumped off the tank and pulled Phil closer to the Sherman’s hull so they could take cover. The radioman then knelt down and carefully ran his hands through Phil’s hair, soaked with blood.

“Just nicked your scalp, Lieutenant, but it’s bleeding like hell.” He reached into his overcoat, tore the wrapper off a gauze bandage, and pressed it against the wound. He tied the gauze cloth in a knot as another flurry of bullets ricocheted off the tank.

“You okay, sir?” the radioman asked.

Phil refocused his eyes as he became more alert. “Yeah,” he said. “Just a scratch.”

“It’s more than that, sir, but we gotta get out of this hellhole!” the radioman exclaimed.

As Phil and the radioman moved back between the tanks and retreating men laying down suppressing fire, enemy fire from the far side of the clearing intensified, coming from three directions. The other men started running as fast as they could for the protection of the trees. Phil was beside the last tank backing out of the clearing, rapidly firing his M1 Garand as bullets shredded the earth around him.

“Take cover!” Phil yelled. He and the radioman grabbed their M1s. The radioman made it behind the rear of tank’s hull as Phil followed. Bullets whooshed through the air, just inches away.

“Sniper! Eleven o’clock!” the radioman yelled.

Phil quickly turned and spotted movement in another tree 100 yards away.

Another bastard is aiming at us!

In a practiced motion, he raised his M1 and squeezed off two swift rounds. The sniper tumbled out of the tree, hitting the ground like a limp rag doll.

His action drew more fire in their direction, intensifying by the second and coming from a wider radius. Phil quickly realized that their position was being overrun. They were too exposed. They needed to get to the safety of the trees.

“We’re surrounded! Get the hell outta here! That’s an order!” Phil cried out to his radioman. “I’ll suppress ’em!”

Phil began rapid fire as the tank moved backward and the radioman started sprinting for the wooded forest behind them, a distance of 50 yards. As Phil took one step from behind the tank to get a better angle on another sniper, a sudden, burning pain seared just below his right knee, as if someone had hit him with a giant club.

He instantly knew he’d been shot in the leg. A second later, he crashed to the ground, groaning in pain. His entire right leg felt numb as blood gushed from a massive wound. Fear surged through him as warm liquid filled his boot.

Then his training kicked in. Phil ripped off his belt and tightened it around his upper leg. Relief flooded him as the spurting flow of blood slowed, but the searing pain brought on nausea.

Looking up, he saw his radioman had also been hit and had fallen to his knees a few yards away. He was holding his hand over an oozing shoulder wound.

“You okay?” Phil yelled.

“Yes, sir. I think it’s a through-and-through. Almost no bleeding.”

Suddenly, out of the clearing, angels appeared. A number of men from Headquarters and Headquarters Company rushed to their defense and laid down a curtain of suppressing fire, giving his executive officer, Abe Fitterman, enough time to come to Phil’s aid.

Fitterman squatted next to Phil and pulled up his pants leg. What he saw caused the XO’s face to turn pale. Phil’s first look nearly caused him to faint as well. Just below the right knee, a gnarly wound the size of a golf ball was still leaking blood. The torturous pain was something he’d never experienced before—way beyond all his previous wounds, including the major injury he’d suffered in the same leg earlier in France.

Abe reached over to the radio on the back of the radioman and grabbed the handset to report that Larimore had been hit.

“How badly?” It was the gravelly voice of Colonel McGarr.

Abe smiled at Phil. “He’s tough. He’ll live, but he has a hole through his leg about the size of a silver dollar.”

“Get him out. Now!” came the order from the colonel.

“Yes, sir. Out.”

Turning to Phil, Abe said, “Phil, the men are safe. Let’s get the hell out of here and regroup in the woods.”

Phil, his face twisted in pain, looked at Fitterman. “Abe, you get my radioman outta here.”

“After I help you, Phil.”

“I think it missed the bone, Fitt.” But Phil wasn’t sure if that was true. What he saw was a much bigger wound than he expected. “I can walk—I’ll use my Garand as a crutch. I’ll be right behind you.”

Fitterman looked at him, skepticism written on his face.

“Abe,” Phil said sternly, nodded toward the wounded radioman, “get him out and call down a TOT (time-on-target artillery concentration) on this clearing and the woods behind. We’ve gotta stop this now. You hear me?”

“I don’t like leaving you. You can’t walk. You’ll be a sitting duck.”

“Go! The TOT will protect me.”

Abe grabbed the radioman, and they ran behind the retreating Sherman as enemy fire from the far edge of the forest intensified and poured in from three directions.

Suddenly, as mortar fire began to shred the clearing, scores of Germans poured out of the woods. Phil tried to stand, but an unimaginably excruciating pain shot up his leg. He collapsed as bullets kicked up the dirt around him. Seeking cover to save his life, he managed to quickly roll away from the tank treads and into a shallow ditch.

Although his artillery and armor fusillade had broken the attack momentarily, Phil could tell they had only temporarily slowed the enemy advance. He could only pray Fitterman would call in the more-concentrated TOT he had ordered to end this onslaught and end it now.

As the Germans inched closer and closer, an ear-deafening concussion was followed by dirt and mud raining across Phil’s body. A mortar had landed only a few yards from him; thank goodness the shallow bank of the ditch provided some protection.

As the TOT intensified, he began to quietly pray—that he’d survive the wound, that he’d see his parents again. In the craziness and danger of the moment, a tune flashed through his mind:

I’ll be home for Christmas. You can count on me.

The melody was shattered by the growing fusillade from his guys, mixed with the fanatical shrieking of onrushing Germans and their hail of small arms fire, causing him to rub the dirt from his eyes. Tracers and bullets screamed past, inches above his head. Despite the unbearable agony, Phil slowly rolled over and peeked out of the ditch.

He felt the color drain from his face as he saw crazed Germans running toward him, screaming wildly like banshees, firing as fast as they could, less than 20 to 30 yards from him, closing fast.

Phil pressed his head into the ground, suppressing the urge to vomit. As waves of pain, nausea, and mind-numbing fear shot through him, he turned limp and played dead. The ruse worked; within seconds, the enemy soldiers leaped over the ditch and kept running.

Not daring to move, Phil thought, “They didn’t see me moving. Maybe I’ll make it.”

Then, the same melody played in his mind:

Please have snow and mistletoe and presents on the tree.

A wave of friendly artillery exploded around him. The earth shook mercilessly from blast after blast.

Thank God for the 155s. They’ll save my men. Maybe me, too.

Phil felt clumps of moist loam shower down on him. He knew the earthen covering would not save him from a direct hit, but maybe it would hide him from the enemy surrounding him.

The violent blasts of the raging battle around him strangely began to wane. Phil’s eyes clouded, and his peripheral vision dimmed. The overwhelming pain began to melt away.

He understood what was happening: he was bleeding out. The belt around his leg had loosened, and he no longer had the strength to reach down and pull it tighter. Soon the world around him was silent, and his body completely numb.

So, this is what it feels like to die. Not as bad as I imagined.

Tired beyond measure, he closed his eyes. He felt strangely at peace. His breathing slowed. He began to recite the Lord’s Prayer.

Although he would miss his mother and father terribly, he looked forward to meeting his Father in heaven. On the eighth day of April 1945, he knew that maybe, just maybe, his long, grueling war was over.

I’ll be home for Christmas, if only in my dreams.

Epilogue

1st Lt. Phil Larimore was rushed to a military hospital where doctors saved his life, but they had to amputate his right leg above the knee. After rehabilitating for a year at Lawson General Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, he fought to stay in the Army as an amputee but lost his hearing in 1947. He returned to college and eventually married and raised a family of four boys in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he made cartography—mapmaking—the focus of his teaching, research, and publishing career as a college professor at Louisiana State University. He passed away peacefully in 2003 at age 78.

Adapted, with permission, from At First Light, released in April 2022 by Knox Publishing and distributed by Simon & Schuster. All of the facts, quotes, data, and statistics conveyed in this article are sourced and cited in the book, about which General David H. Petraeus writes, “This story is extraordinary: an almost forgotten hero, tough combat, tragic sacrifice, gripping aftermath, a marvelous horse, and an astonishing ending. Don’t miss reading this remarkable book.” For more information about the author, please visit www.DrWalt.com.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments