History is like a limitless forest. More out there than you can ever take in. Turn over a stone and who knows what discoveries abound. Take the Sino-Japanese War of 1894. It is little known in the West, but few swift contests have been so pregnant with distant disaster.

The initial causus belli was Korea. The peninsular country appended to the Asian continent had traditionally been under the influence of China. But Japan had long viewed Korea as a dagger poised at its heart, a sure path of invasion. In the early 1890s, China and Japan officially viewed Korea as neutral, although China held the upper hand.

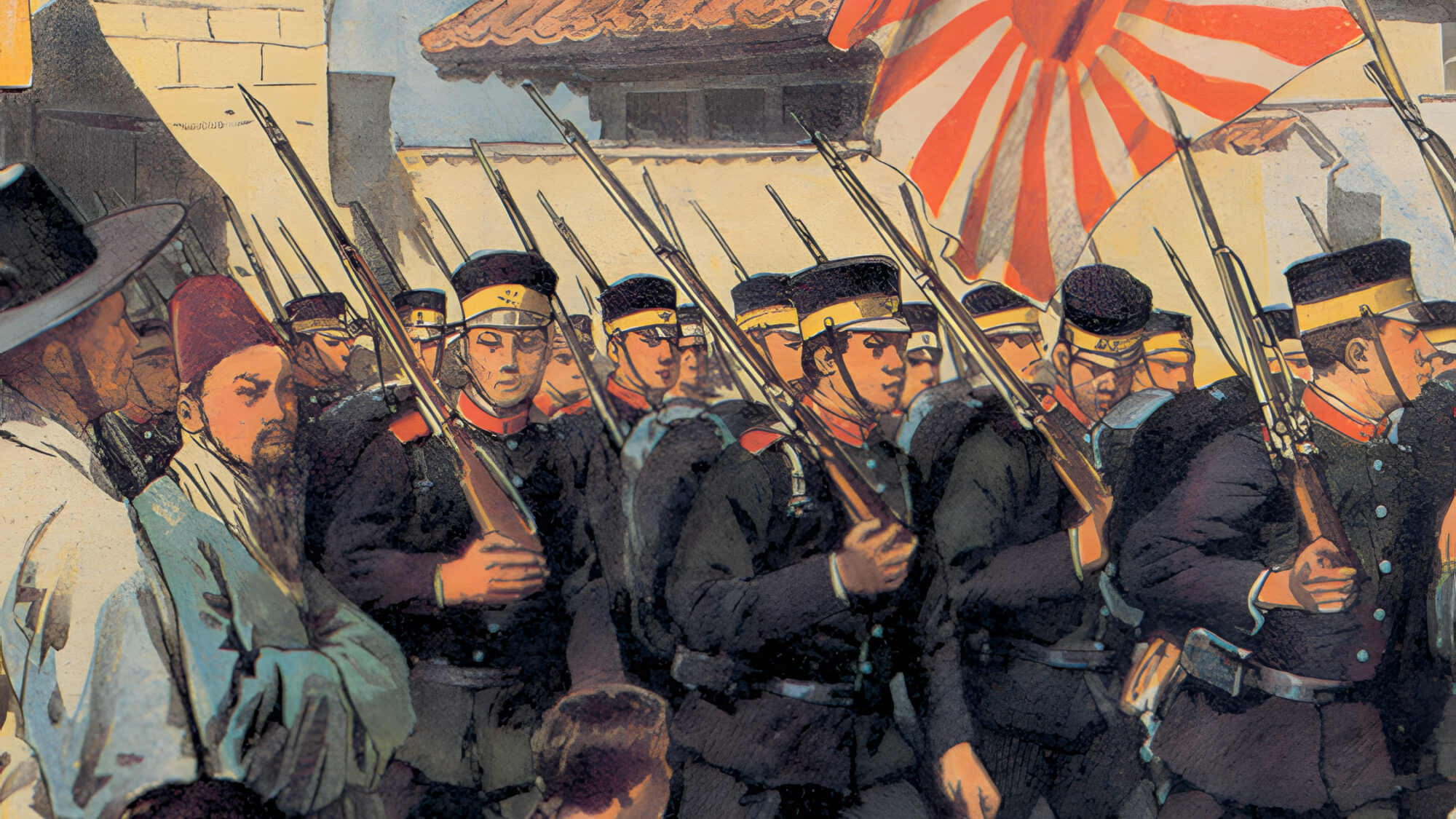

This was a time during which China and Japan were reacting differently to the European presence in Asia. China preferred to hearken to its thousands of years of traditions, ignoring as best it could the white man’s encroachments and retaining its sense of superiority. Japan gave over that notion at mid-century and felt the best way to deal with Westerners was to at least meet them at their own game; they adopted Western technology and management techniques.

In this endeavor, Japan began to look, not inward at its own lands as it had for centuries, but outward, beyond its borders. It felt that its preservation and prosperity depended not only on its own people, but also on land masses nearby. Under its control, Korea would not only thwart invasion, but it would provide agricultural and resource benefits. If this sounds like European imperialism, it is. The last half of the 19th century marked the height of European incursions on Africa and Asia for economic benefit. Japan saw the Europeans’ gain and, as in other matters, followed their example.

When rebellion arose against the weak Korean government in 1894, the Koreans called for aid from China. Japan countered with a like number of troops in order to maintain “neutrality” there. Soon the Japanese troops seized the Korean king forcing him to order China’s withdrawal. Two days later, Japan attacked a Chinese ship bringing reinforcements and the two powers declared war.

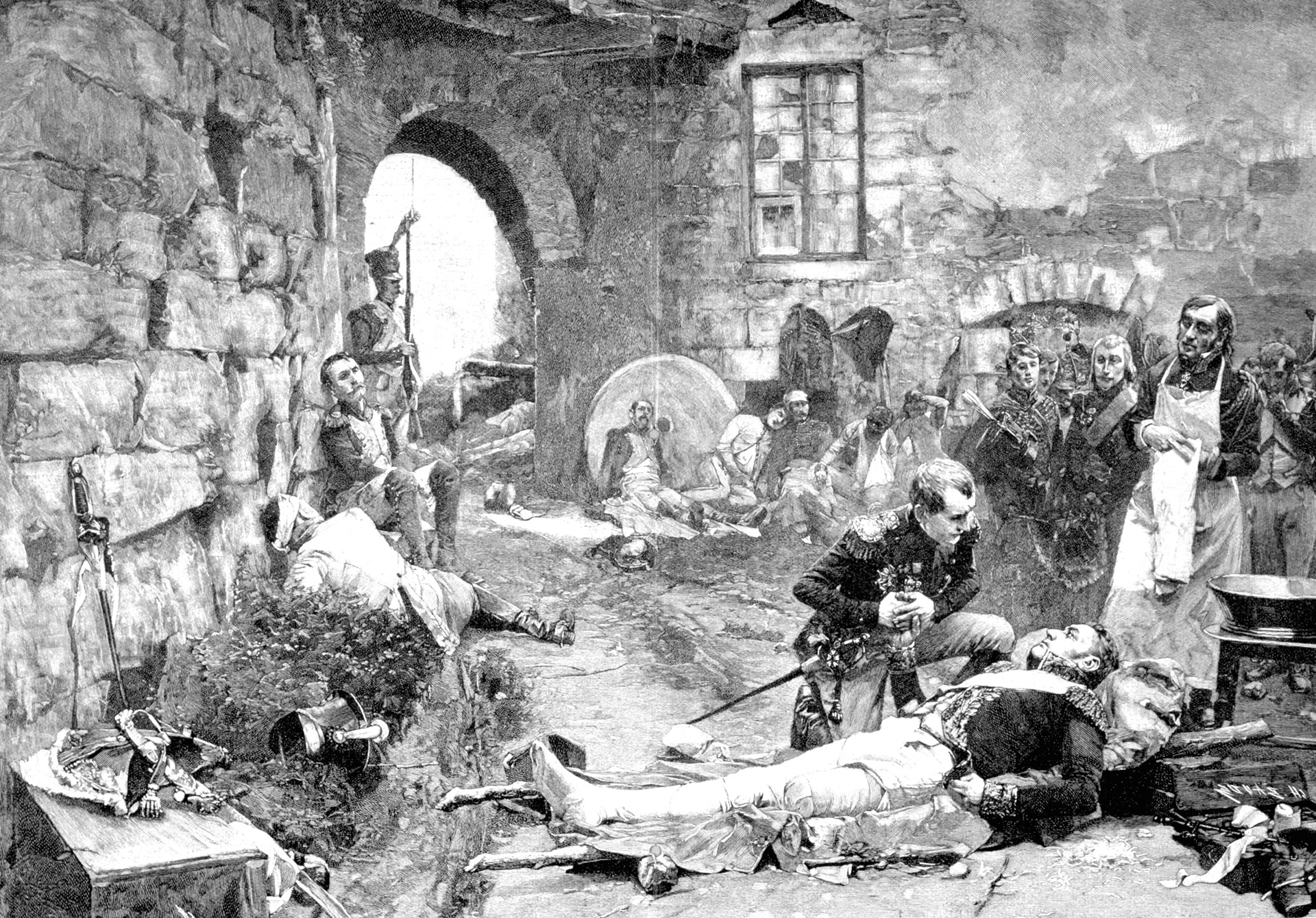

Most observers thought China would win a military struggle, its army being far larger. In fact, the Japanese drove the Chinese out of Korea in swift, one-sided battles and demolished her sea power offshore. Japan then invaded the Liaotung Peninsula of Manchuria, on which Port Arthur stood, and the large island of Formosa, as well as other Chinese territory. China sued for peace.

Japan demanded virtual control of territories it had conquered along with indemnities three times larger than its recent annual budgets. This the Japanese got, except that Russia was so appalled by the concessions that it enlisted Germany and France (arguing Japan would otherwise in time roll up all of Asia) to help rescind one of the treaty provisions—Japan had to surrender control of the Liaotung Peninsula to Russia, which itself felt the need to control Manchuria for its access to Vladivostok.

The Japanese were quietly furious, further convinced that Europeans were hypocritical and determined to thwart them. They redoubled their efforts to build up their military. They learned other lessons from this swift war as well: The Westernization of their army and navy was effective; they could best the Chinese as well as any European power; they could make land grabs as well as white men and keep at least some; their ruthlessness in battle reaped huge rewards; and their slaughter of innocents (in their occupation of Port Arthur) went largely uncensored.

This brief conflict not only laid the foundation for the war in 1904 with Russia over Port Arthur, but also would be mirrored in Japanese empire building through the first 40 years of the 20th century as well as the grab for territories that compelled its war on the United States in 1941.

The sharp victory in 1894 whetted Japan’s appetite for military conquest, which would not be slacked until 1945. Well might brighter minds in that country and others have seen in it the spark of terrible light with which the world was set aflame in the 1930s and 1940s and determined how it could be properly extinguished.

Brooke C. Stoddard

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments