By Peter Suciu

There is an old saying that the pen is mightier is the sword, but try telling that to anyone under fire and they will likely disagree. They might also say that a war of words does not go far in a firefight but then explain how communicating with comrades while under fire can change the situation quickly. Ever since man went to war, there have been codes, ciphers, and other ways to protect valuable information from falling into enemy hands. In World War II, while the Germans relied on the advanced technology (at least for the day) of the Enigma Machine, code breakers were able to unscramble the information and oftentimes had the dispatches almost as quickly as they went out.

But this never happened with the United States Marine Corps, using the Navajo code talkers in the Pacific Theater. Movies and TV shows have shed some light on their activities, but with less than 50 of these former soldiers still with us, their story has not been told completely.

Three of the surviving members, Peter MacDonald, Sr., former chairman of the Navajo Nation and code talker with the 6th Marine Division; Frank Chee Willetto, former code talker with the 2nd Marine Division; and Bill Toledo, former code talker with the 3rd Marine Division, ventured to New York City some months ago to march in the annual Veterans Day Parade. Following the event, they sat down for a candid interview about what it meant to be a real warrior with words and to describe how they hope to preserve their legacy with a museum devoted to the men and the code.

Peter Suciu: Growing up in the southwestern United States, did you ever expect to see as much of the world as you did serving as code talkers with the United States Marine Corps?

MacDonald: Not me. You can ask Frank here.

Chee Willetto: Well, young people, or at least most young, think about what they’ll actually be doing. For my part, I was just going to school, and many of my friends were leaving to go into the service. I couldn’t leave because I was under age and I had to finish the eighth grade at the time. That was why I feel that it was mostly my buddies leaving, which was why I also wanted to join. But I found out that I couldn’t do it because I was completely under age, and they wouldn’t accept me anyway. However, I finished the eighth grade and had gotten a job in 1943, and six months later I was drafted, but only because I had lied about my age so I could be drafted.

Toledo: For me, yes. When I was recruited I was told I’d get to see the country and the world, which I did.

You saw these places obviously in very hostile situations, so did you ever get to return and see any of the places where you had fought after the war?

Toledo: No, not really. But I did get to visit Japan in 1993 as a tourist. I went over there with my daughter. She had been invited by another teacher to make a presentation and spent three weeks there. We were very well received, but I did meet one Japanese veteran who served in World War II, and I asked him what he thought of the Navajo code talkers and how the Navajo language was used. He gave me a really hard look and just got up and left. I can understand why.

MacDonald: Well, those of us who were in World War II—I’m talking about Navajo—grew up in a world that was nothing but Navajo. Until I was nine years old I didn’t know anyone but Navajo lived in this universe. This was until I began to see white men with whom we traded from time to time. And from time to time you would see other tribal members. But other than that, my thought was that this world was made up of nothing but Navajos. And so we did our thing: herded sheep, took care of the animals, raised cattle, and farmed. We practiced our ceremonies and our religion and tradition and things like that.

But I didn’t think of the Navajo as Indians. We watched cowboy and Indian films, and I didn’t think of Navajo as Indians. At least I thought of the Indians as some other people with feathers, because the Navajo didn’t wear feathers. And we didn’t dress in buckskin, like you see the typical movie Indian. So my thought was that I was a Navajo and those were Indians, and they are different. They live different and they talk different, and of course they fight with the cowboys and cavalry. We all wanted to be the Lone Ranger, and no one wanted to be Tonto.

When did that begin to change for you, and what were your experiences with the larger world actually like?

MacDonald: It was when we were exposed to education. I was put in a day school, and from morning to about three o’clock I was in school. My parents and I thought it was to learn and write the English language, period. Then when I was in ninth grade I was put in boarding school. It was a government-run boarding school with the objective to “civilize” us, to get us out of our traditions and culture and things that we were accustomed to. So, one of the things they were using to so-called “civilize” us was for us not to speak our language. They prohibited us from speaking Navajo, and every time we spoke Navajo we were punished terribly. So no one wanted to accidentally slip in a word or two. And that went on. It was kind of a like being in the military. We marched everywhere.

But when the war came on, after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, that’s when things changed. One of the boys at school had a radio, and we heard about the war, and finally Pearl Harbor. But never in my mind up until that point did I think I would be in the military. Although, like any kids, we played soldier and other games. I was 15 years of age when I joined the United States Marines in 1944.

Obviously, the first group of Navajo went in for the purpose of developing a special code, a military code, back in 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor. Then, of course, when it was realized that the Navajo code was very successful, they started recruiting more and more Navajo to join the Marines. When I joined in 1944 I began to see there was much more beyond the Four Sacred Mountains where we lived.

It was something seeing the outside world. There were cities with skyscrapers that looked like the canyons in our world, and of course all sorts of different people, black people, Chinese people, and white people. Most strange for me at the time was that the languages were all so different. And, of course, the Marine Corps language was also different! It was a military language and we had to learn all of that.

Did you expect to be a code talker from the beginning?

Chee Willetto: I didn’t volunteer. I was drafted, but I lied about my age so that I could be drafted. When I was drafted, a sergeant came up to me and asked if I was a Navajo; I said yes and he told me to come with him. I was sent to a Navy doctor for the physical, but it wasn’t really much of a physical, because he only asked me four or five questions and he said, “You passed the physical.” That’s how I got involved in San Diego and got to be in the Marine Corps.

So for you everything really happened quite quickly?

Chee Willetto: Yes. After that I went to basic training for eight weeks, and after that went to Camp Pendelton, and I found myself with more Navajos in the barracks. And then I found out that we’d be carrying communications equipment. At that time I did not know we were going to use our own language. I later heard that the first 29 Navajo who volunteered had made the code, and I had to be taught the code.

What was the training like to learn the code?

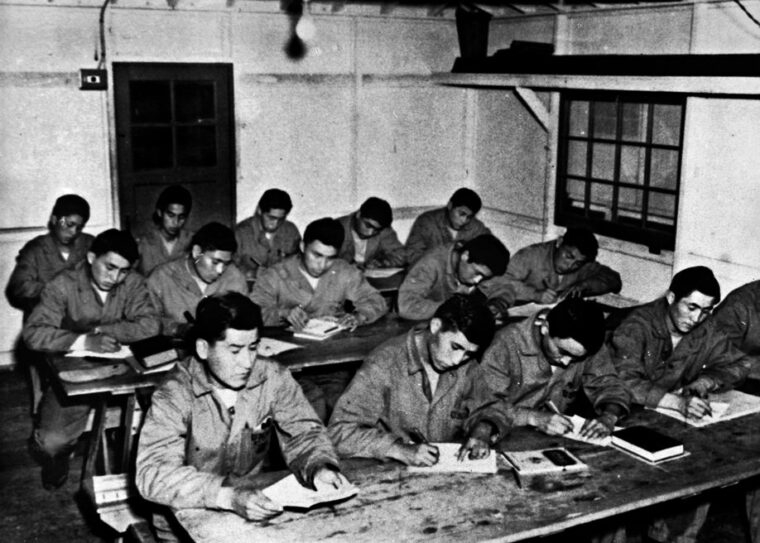

Chee Willetto: The first thing was that there was no paperwork; everything had to be memorized. We couldn’t go back to our barracks with anything. Nothing. So after another eight weeks, I found myself on a ship to go overseas to the South Pacific. We were shipped out to Hawaii, where we spent more time, and then we went north to the island of Saipan.

MacDonald: We were segregated to learn the code. The Navajo language itself is difficult to learn but was coded [by the Marines], so that not even a Navajo who had not gone through code school could tell what we were talking about. That was why a place was set aside at Camp Pendleton, which was under guard all the time, like the Manhattan Project. Those of us who went in and learned the code couldn’t take notes out of the classroom. That was why the code was never broken by anyone, particularly the Japanese, who could never decipher it. But more than that, it was very efficient.

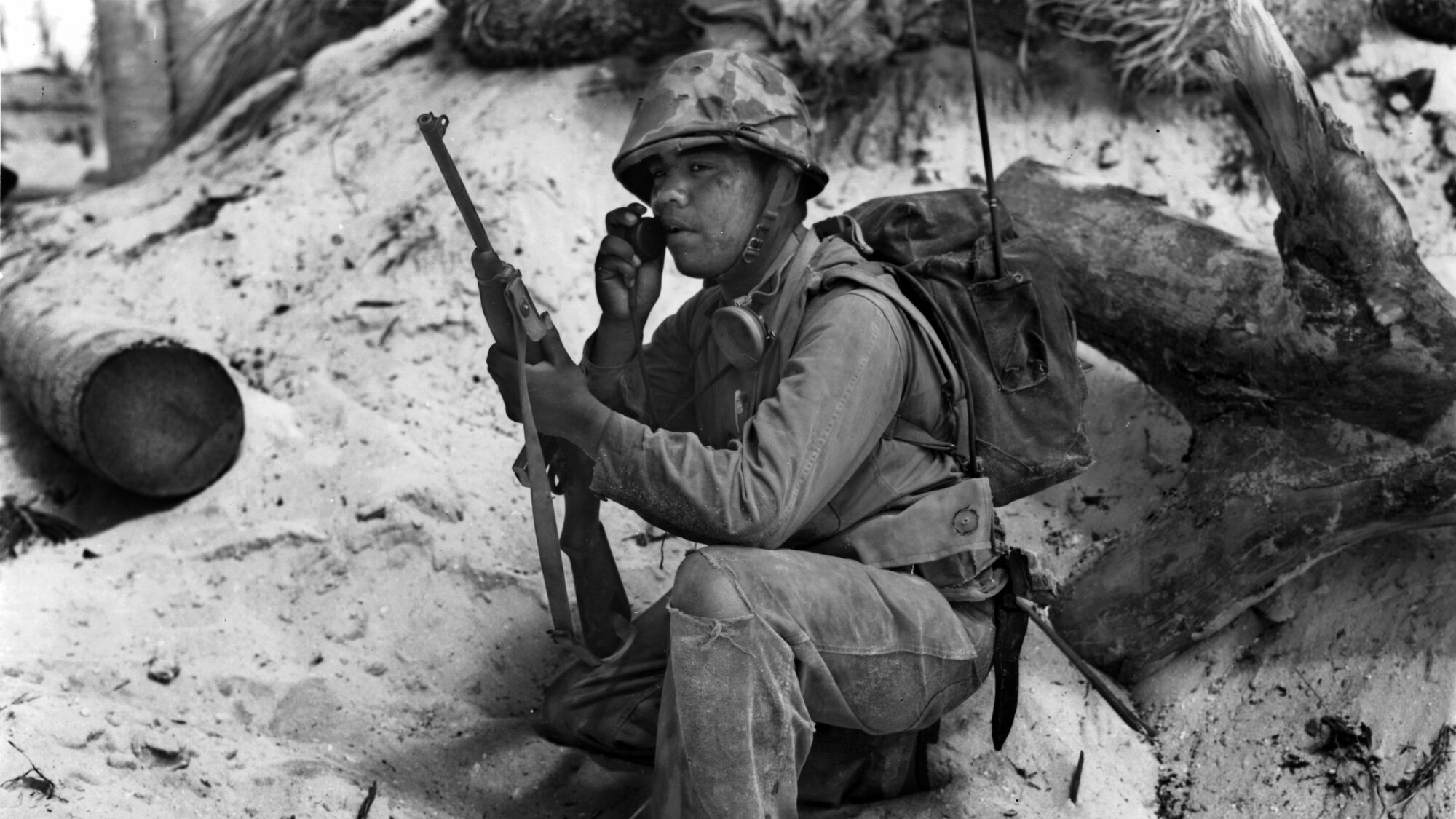

You could write something down in English, but when the code talker starts reading it in Navajo he is coding it. On the other end, the Navajo hears Navajo words coming in and he decodes them as he is hearing them. The speed and efficiency of this is fantastic, as opposed to other methods of coding and encrypting a message. Sending a messaging and deciphering it with a machine can take anywhere from half an hour to 40 minutes, maybe even an hour or more. But our system using the Navajo code was very fast. It might take us only 30 seconds using the regular system.

Unlike some of the other codes that were used during World War II, which relied on technology such as the German Enigma machine— and its code that was broken once the machines were captured—the Navajo code was never compromised. What do you make of that?

MacDonald: I don’t know anything about the German machine. The Navajo code was never broken until 1968 when it was declassified.

The thing to understand is that it was a special language and a code. We talk Navajo, but that’s not the military code. There was a special code using the Navajo language and that remained a secret up until 1968. Only then did we become aware of how valuable our language and our work had been to the greater war effort.

Were you surprised to be reminded of your efforts?

MacDonald: By that time, many of us had forgotten about the whole thing. Then the code was declassified and headlines went across the country and announced how it was used and how code talkers used their language. We had to remember what we did.

The military already had other codes in use. What made the Navajo code so special?

MacDonald: Why was a special code even needed? No one really even talks about that part of it. The Japanese were intercepting and decoding all of the military codes that were in use at the time, particularly in the Pacific. They knew exactly where we were going to be at a certain time and what sort of equipment we were going to be delivering and using. And they’d be waiting for us at the other end. It was difficult to spring any sort of offensive maneuver without the enemy knowing about it.

So, they needed a code that the Japanese could not understand, and more importantly was unbreakable. So they searched and came upon the Navajo language. Why did the Marines choose the Navajo language as opposed to the Cherokee language or some other language? The Navajo language was chosen by the United States Marine Corps and the United States Navy because they were having all the problems with the Japanese in the Pacific. Once it was decided, the first 29 Navajos that went in just a few weeks after Pearl Harbor developed a code that not even another Navajo could understand. That became a successful code, and more and more Navajo were recruited as the war went on. At the height of the war there were over 400 of us who learned the code and used it.

So it was used throughout the Pacific Theater in World War II?

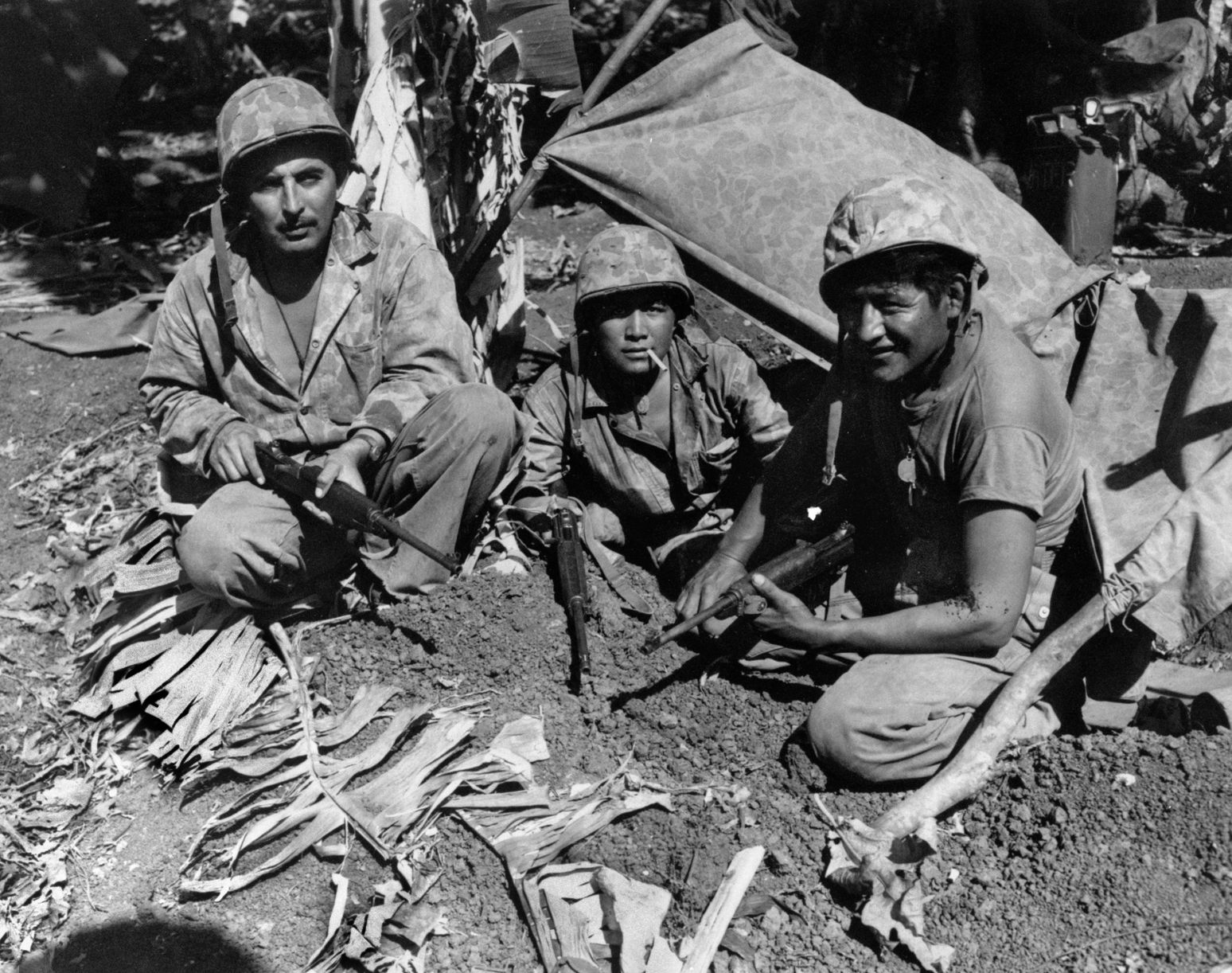

MacDonald: It was used all the way from Guadalcanal to Tarawa to Palau, Bougainville, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. In all those major invasions the Navajo code was progressively used by the military, from ship to shore, shore to ship, and ship to ship. In some cases it was even used from behind enemy lines. It was used to relay back to headquarters, and to direct gunfire, report battlefield conditions and the other situations out there that were critical.

Of course, we didn’t know how effective it was until much later. It is a story that deserves to be told.

Many people only got this story from the movies and TV, notably John Woo’s film Windtalkers. Have any of those gotten your story even close to the actual truth?

Chee Willetto: No. Many books were written, but they don’t really tell the whole story.

MacDonald: The movies, such as Windtalkers, only tell maybe one-tenth of the story of what Navajo code talkers are about. There are also many documentaries out there, and they are fine, but they only tell a small part of the story.

What are you doing to get the story of the Navajo code talkers finally told in its entirety?

MacDonald: What we are working on right now is a national Navajo code talker museum. We want to tell everything. A lot of the way the code was developed was cultural, and it is part of our traditions, and that isn’t being told. Today we live in a different world than what we lived in back in the 1920s and 1930s. So the times have changed. If you tried to develop a Navajo code today you might not be as successful as the code talkers were back in the 1940s. That needs to be told.

People need to be told why it was developed, how it was developed, how it was used, and, most importantly, how effective it was in terms of saving lives and helping to shorten the war in the Pacific. We want this museum to help tell that story. We also want the museum to be a learning center for our young people today.

So again, you never thought about the notion of code talkers until later?

MacDonald: During our service they referred to us as radiomen, and we didn’t know we were “code talkers.” We carried radios like everyone else, and we were in the communication system for the Marines. Some of the men were using English to transmit. The difference was we were using our language and a code to transmit messages.

During your time in the service, you were also more than just code talkers, of course. You were first, last, and always riflemen, as is every Marine.

Chee Willetto: I wasn’t treated as a communication man, but I was treated as an infantryman. Being educated as a communication man I thought, “Why should I be carrying that light machine gun?” Of course, for the first eight weeks we had to learn how to use the equipment just like any other Marine, and then after that we went to the code school. As code talkers we were being used everywhere, so we were Marines, and we were also code talkers. We did what we were needed to do.

Where did you use the code?

Chee Willetto: My first encounter using the code was when I arrived in Saipan. I later took part in the invasion of Okinawa, and while we were doing that my legs and ankles got swollen and I couldn’t even move them.

My sergeant found out what happened, and finally I was on the ship and floating around for two weeks. They were doing a good job over there, so I returned to Saipan where I was sent to the hospital, and I was still there when a whole lot of shouting went out until a guy came in and said, “The war is over.”

While the movies and books may have gotten some of the facts wrong, do you think this has at least given attention to what you did during the war?

MacDonald: Absolutely. It has brought up more questions. More requests for appearances to hear our story have come about. Now, unfortunately, there are less than 50 of us left. And we’re older now. I’m 83 and probably the youngest of the group—there are guys who are 95 years old. So there are less than 50 of us, and we want to tell our story.

And this brings us to back to why we want the museum to house our story. This is a Navajo legacy; it is an American treasure and an American legacy. Our children and your children need to know this story and how this code was developed, why it was needed, and how it was used. We also want to honor and pay tribute to all veterans who served with us, because it was not just the Navajo language or the Navajo code talkers, there were many others who served with us in every battle across the Pacific. There were Navy, Army, Coast Guard and, of course, Marines.

So, this is to honor them and those who never came back—who died on the beaches and battlefields out there. We are asking for help, and we are asking for volunteers, just as we volunteered to help back in 1942 to preserve freedom and liberty. And that’s why we’re asking for help with this project.

Where will the museum be located?

MacDonald: It is going to be within the Four Corners area. The Navajo nation encompasses the four states of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. Our sacred mountain is within those four states, and the museum is going to be right on the eastern edge of the reservation in New Mexico.

Chee Willetto: The Navajo code talker museum will be built on 240 acres of land that the Chevron mining company gave to the code talkers, not just to the Navajo nation. It will include a veterans center, where veterans can come in and meet with other people. Veterans that served together can finally meet up again.

We think this is something that can certainly happen. We helped the United States when it was threatened, and we think that this is a story that needs to be remembered. The museum will be a place where the code talkers can share their stories. It is easy to think that every code talker who served in the military had the same story, but they all did something different. You can’t just walk in and talk to one code talker and think that tells the whole story.

We hope all of the 50 remaining code talkers are there to see the opening.

MacDonald: We pray that all 50 of us will be there as well, yes! And we hope to honor those who went on before us. They did something important too!

You came to New York for the November 11 Veterans Day Parade. How was that experience?

MacDonald: Very good. It was very exciting, exhilarating, and simply stupendous. The crowds were just unbelievably thankful of the all the veterans who served and who are now serving. I think that is a real good picture of what America is all about. We enjoyed it. At least I did.

Toledo: Someone passed the word, and we were very well received, and I really enjoyed it. I saw people carrying signs that said, “Thank You.” That was very nice.

Chee Willetto: There was so much response from the streets that I had never seen before.

MacDonald: Coming to New York gave us a good feeling about why we served, and the sad part of the whole thing, at least from my point of view, is that so many with whom we served were not there to enjoy this honor and tribute. I only wish they were here. They passed on, and too many of them are still on those faraway islands in the Pacific.

Author Peter Suciu is an expert on military headgear and a resident of New York City.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments