by John Wukovits

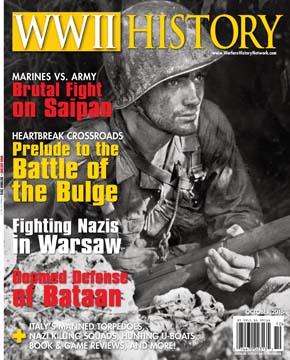

Normally, the end of combat brings satisfaction and a sense of relief, but the Army infantrymen and Marines who slugged it out with the Japanese at Saipan experienced little of either. Instead, shock and revulsion took their place. On Marpi Point, a rise lifting out of the ocean on Saipan’s northern shore, the American victors watched helplessly as thousands of men, women, and children chose to die rather than surrender to an enemy they had been told would torture them.

[text_ad]

The Americans could do little to halt the tragedy. They rushed from their foxholes to help, but only succeeded in hastening the suicides or dying themselves in a hail of Japanese bullets. Civilian parents strangled or stabbed their children, groups of people joined hands and leaped to the rocks and water below, and distraught women waded into the surf until they disappeared.

On the beach, one family of five walked toward the water to commit suicide, but changed their mind and started back. A Japanese sniper hidden in a nearby cave killed the father with one round, then shot the mother with his second. Marines watched in horror as the sniper turned his attention on the three children, but another civilian rushed out of a cave and saved the youngsters. A few moments later, when the Japanese soldier emerged, hundreds of incensed Marines literally disintegrated him in a withering hail of gunfire.

American destroyers moved closer to shore in hope of rescuing some of the civilians, but they had to navigate carefully to avoid mangling anyone in their blades. On shore, some Marines who had rescued babies wandered about the beach, gently holding their tiny bundles, looking for powdered milk. One huge Marine, his face covered with battle grime and blood, sat on a road with a six-year-old girl, tenderly brushing flies from her shocked face as tears coursed down his cheeks.

The gruesome spectacle was later used to warn American soldiers what to expect in the invasion of the home islands. If Japanese soldiers reacted with such fanaticism on an island hundreds of miles from Japan, one could only wonder what might unfold as the Americans ground their way toward Tokyo. Thanks the atom bomb, the Americans would not have to face that eventuality—and neither would Japanese civilians, a fact conveniently ignored by critics of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On Saipan today, Marpi Point remains an emotional spot for many islanders. Superstition holds that before the suicides, Saipan had no white birds. Today, many soar above Marpi Point’s cliffs, each supposedly containing the soul of an islander who died there, pointlessly and tragically, in June 1944.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments