By Eric Niderost

On March 12, 1938, German troops entered Austria, part of Adolf Hitler’s plan to incorporate that hapless country into the Third Reich. Bullied, browbeaten and ultimately broken by Hitler’s rants and endless threats, Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg threw in the towel, in effect agreeing to “Anschluss,” unification with Germany. Schuschnigg gave a radio address in which he sadly explained, “We are not prepared … to shed blood” to defend the country against German invasion.

Hitler entered Vienna three days later and celebrated his triumph by making a typical bombastic speech before a crowd of 250,000 people. In the days following the Fuhrer’s visit a wave of anti-Semitic intimidation, destruction, and violence swept over the city. Vienna, the cultured metropolis that celebrated Beethoven, Mozart, and Strauss, also had an ugly, darker side that hated the Jews after their numbers increased in the 19th century. When the Nazis took over, this long dormant anti-Semitism sprang to malevolent life.

Viennese mobs roamed the streets, smashing Jewish-owned shops, beating and humiliating every Jew they could find, often forcing them to scrub the streets on hands and knees. There’s a story of an SS officer supervising a group of Jewish women scrubbing, when he noticed they had been joined by a man— well dressed, even dapper, balding, with a thin mustache. The puzzled SS officer ordered the stranger to produce an identity card.

The Nazi officer looked at the ID with a mixture of shock and incredulity, handed the document back to the man, and curtly ordered the women to stop working and go home. The officer reasoned that he would be held responsible for the man’s continued humiliation, and it was better to release everyone than to risk reprimand.

The man with the mustache was Albert Göring, brother of Luftwaffe chief and Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring. Albert loathed Hitler and despised the Nazis, yet maintained a cordial and even loving relationship with his brother, who was considered in the 1930s to be second only to Hitler himself in the Nazi hierarchy. Yet even more amazing is the fact that Hermann knew about Albert’s activities, at least in general, but never condemned or abandoned him. Quite the opposite; Hermann went to great lengths to protect his brother from arrest, imprisonment and possible death.

Their father, Heinrich Göring, devoted his life to Imperial Germany’s diplomatic service, first as Reichskommisar (administrator) to the colony of German Southwest Africa, later as German Consul General to Haiti. Sometimes his wife, Franziska (“Franny”) would accompany him overseas. He was often away from Germany and the family for long periods.

Heinrich ended his foreign service career on a note of bitterness and semi-failure. He drank heavily to forget his limited resources, wife and five children. But, out of the blue, a savior arrived in the person of Hermann von Epenstein. Epenstein was an enormously wealthy physician who had an opulent lifestyle. As godfather to the Göring children, he offered to take the whole family under his wing and provide for them for as long as was needed.

Around this time, Fanny Göring became Epenstein’s mistress. Apparently, she went into the relationship quite willingly and became the “unofficial” wife/hostess at Epenstein’s palatial estates at Mauterndorf and Veldenstein. Heinrich Göring also gave his tacit approval to the affair, which freed the family from financial worries for years to come.

The future Luftwaffe chief was born in 1893, two years before Albert. As they grew older, the boys understood the “special” relationship their mother had with the society doctor but had no problems with it. They grew up in almost royal splendor, where each day at Castle Mauterndorf was a medieval fantasy where hunting horns blew to announce dinner and Epenstein reigned as lord of the manor.

Epenstein was a larger-than-life figure who made a great show of his devotion to the Catholic Church, though he was actually Jewish and had converted probably for social, not spiritual reasons.

As young men Albert and Hermann were polar opposites. Hermann was the risk taker, the overachiever, and the man who aspired to be a great warrior in an almost mythic “Wagnerian” German way. He chose a military career, and when World War I broke out eventually became a pilot with Baron Manfred von Richthofen’s famed “Flying Circus” squadron.

Albert was shy and introverted, but did well enough at the Technische Hochschule, a science and technology school whose main emphasis was on innovation to advance German industry. When war came Albert became a signals officer in the trenches, but as soon as peace was declared he went back to civilian life. A military career was not for him. In the 1920s Albert worked for IG Farben, at time the biggest corporation in Europe and a giant in the chemical engineering world. It is not known if Albert and Hermann had much contact in this period.

While Albert prospered, Hermann went through a period of depression and addiction. Wounded in Hitler’s failed Munich “Beer Hall” coup in 1923, he eventually became a morphine addict to combat the pain. Hermann did kick the habit, but in the late 1930s he started taking a sedative, paracodine, a mild morphine derivative. By 1945 he was taking 20 pills a day.

When Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933, Hermann’s future was assured. By the mid-1930s he was at the height of his power, head of the growing German Luftwaffe and Hitler’s right-hand man. Albert loathed the Nazis and wanted no part of his brother’s sudden rise to wealth and fame. In fact, he got out of Germany altogether by taking a job as technical director of the Tasha-Sascha Film Industry Ltd., a company that was based in Vienna.

And that is how Albert happened to be on hand when the Nazis took over Austria in 1938. But the street scrubbing incident was only one tiny gesture; Albert wanted to do much more. Almost as soon as German soldiers appeared in the streets Albert swung into action. As a first step, he made efforts to save friends and work colleagues. He knew there was only so much he could do, but he would rather light a candle than curse the darkness. He was going to save as many as he could.

William Szekely was a Jewish-American director working in Vienna on a movie with beautiful German actress Zara Leander. Leander later recalled, “We were stuck in Vienna. All ways of getting the necessary papers had been exhausted. Every day friends were arrested and bank accounts confiscated. Albert Göring helped us out… He organized exit visas… went to the bank for me and brought the contents of my account so I would not be without funds.”

And Albert didn’t rest there. Dr. Max Wolfe, his personal physician, was also Jewish and in great danger of arrest, but the doctor’s wife gratefully recalled “just to mention his (Albert’s) name was protection.” Göring not only got exit visas for the doctor and his wife, but also had Wolfe’s brother released from prison and “got him an exit visa, too.”

Tired of living in a city dominated by storm troopers and Nazi functionaries, Albert finally left for Rome to take a position at the Tobis-Italiano Company. While in Rome he made the acquaintance of a Dr. Kovacs, who was anti-Nazi, anti-Fascist, and eventually would have links to the Hungarian underground that helped the Allies. Kovacs was also Jewish, which made him suspicious of Albert at first.

Albert started giving money to Kovacs “for the assistance of Jews and other refugees from Nazi tyranny.” It was said he required “no receipt and no knowledge of who was helped.” The funds were used to help Jews and other refugees to escape to Lisbon. Kovacs was reluctant at first to take the money, thinking perhaps that it was a trap, but he came to realize Albert’s anti-Nazi stance was real.

In June 1939, Albert got an offer to be the export director at Skoda, the famous Czech armaments factory. The Nazis had taken over the country, and planned to liquidate Skoda, moving the machinery and equipment to Germany. Skoda hoped putting Hermann Göring’s brother in the firm would forestall this.

Albert, whose wife had recently died of cancer, accepted and moved to Pilsen. Czech employees were astonished that this brother of the second-ranking Nazi hated Hitler! There was no photo of the Fuhrer in Albert’s office, almost mandatory in most places. He refused the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler!”— answering, “Gruss Gott!” (God bless!) in response.

Albert continued to help Jews and others suffering under the Nazi heel. Sometimes, he had to improvise. Dr. Josef Charvat was a Czech resistance leader who soon landed in Dachau. When his wife appealed to Albert, he took a piece of letterhead paper that bore the Göring name and coat of arms and quickly wrote a message ordering Charvat released at once. Albert signed it “Göring” in bold letters, copying his brother’s hand.

The ruse worked. Charvat was released as soon as camp authorities read the order; such was Hermann’s power at the time. No questions were asked. Albert also regularly asked camps for slave laborers, sending trucks to pick up the workers. In remote areas, the prisoners would be freed and allowed to escape.

The sheer scale of Albert’s activities brought him to the attention of the Gestapo—the secret police, ironically, founded by Hermann. The Gestapo twice issued orders for Albert’s arrest that were quashed by Hermann. The Nazi authorities were frustrated by Albert’s persistence in helping the Jews. In fact, the Gestapo started asking themselves, “…will this public gangster (Albert) be allowed to continue?”

Sibling affection apart, why did Hermann constantly rescue his brother from imprisonment or death? The key to answering the question lies in Hermann’s complex personality.

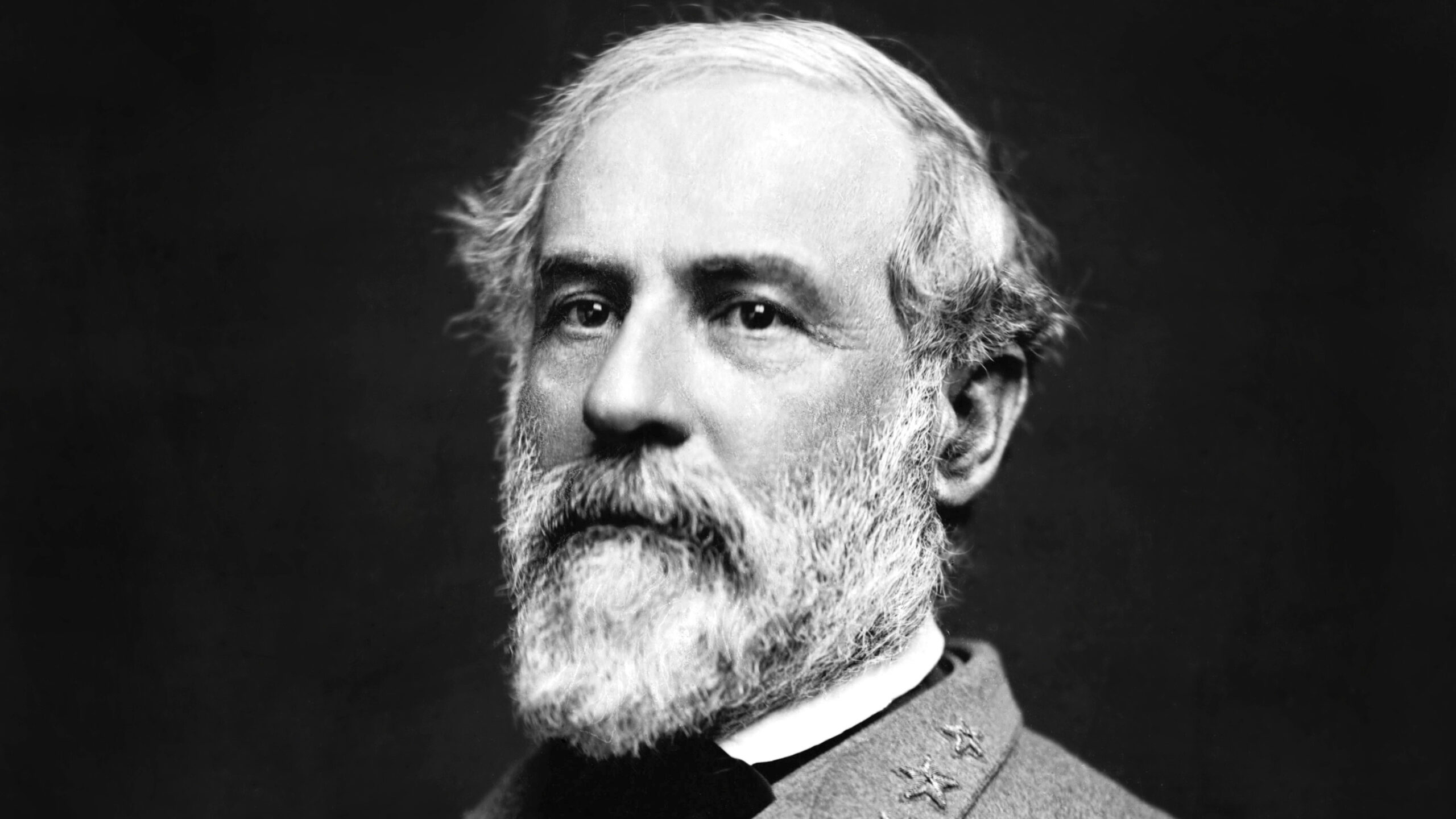

Hermann Göring possessed a Machiavellian morality, where the end—Nazi triumph at home and abroad—more than justified the means, even if those means condoned atrocities. The Reichsmarshall freely engaged in the persecution and economic exploitation of the Jews and almost certainly knew something about the Holocaust, though during the Nuremberg trials after the war he claimed ignorance.

The extent of Göring’s knowledge of the Holocaust is a moot point. In the judgment at Nuremberg, and the judgment of history, he is guilty as charged. But Professor Christopher Browning has identified two strains of anti-Semitism in Germany in the Nazi years: “chimeric” and “xenophobic.” The chimeric believed that Jewish people were untermenschen, subhuman vermin responsible for most of the evil in the world. Hitler and Heinrich Himmler were chimeric, determined to rid Germany and Europe from this “pestilence.”

By contrast the xenophobic believed the “Jews” were master manipulators who had too much influence in German life. Hermann was of this persuasion, but it seems he did not “hate” Jews in an overtly racial fashion. In fact, the Reichmarshall once said, “I determine who is a Jew!” and occasionally protected people like Luftwaffe Field Marshal Erhard Milch, whose father was Jewish.

That meant that while Hermann tried to dissuade his brother from helping Jews, he wasn’t going to actively stop him or disown him as a family member either. In the same situation a racist like SS chief Heinrich Himmler would have abandoned Albert to his fate, and perhaps even personally issued arrest orders.

Albert’s job at Skoda became a peripatetic one, with him a kind of “traveling salesman” for the company in Bulgaria, Rumania, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Greece. But whereever he went, his anti-Nazi activities continued unabated. He did what he could, even though Albert knew the sheer scale of Nazi crimes made his efforts seem almost insignificant. He was always seeking new ways to release prisoners and, when all else failed, he simply forged his brother’s signature on documents.

Toward the end of the war, Albert’s loathing of the Nazis caused him to be indiscreet— and conversations were reported to the Gestapo. In one instance, Albert told friends that Hitler was the “greatest criminal of all time.” Once again, Hermann stepped in and saved Albert from persecution, but it was getting harder.

In Bucharest, Rumania, Albert was playing the piano and singing Viennese songs with some friends when he stopped a moment and heard someone singing in German across the street. Investigating the noise, he saw it came from two German officers on a nearby balcony.

The two German officers, spotting Albert, asked him his name. “Albert Göring,” came the swift reply. “Are you related?” they asked. “Yes, he is my brother,” Albert answered, and as soon as they heard the response they stood to attention and shouted, “Heil Hitler!” Bemused by their reaction, Albert told them, “Kiss my ass!”

Hermann Göring still had enough influence to get his brother off the hook, but by 1943—if not earlier—his power was definitely in decline. Göring’s boasts that his Luftwaffe could do everything did not coincide with the facts. The Luftwaffe did not win the Battle of Britain in 1940, and in 1942 could not adequately supply the trapped Sixth Army at Stalingrad. But most of all, the Luftwaffe could not stop the Anglo-American bombing raids, which increased in intensity year to year.

Albert was truly the “black sheep” of the family, giving Hermann endless troubles. In fact, there were gasps of horror in Nazi circles when he declared he was going to marry Mila Klasarova, a very lovely former beauty queen who was over 20 years younger. It wasn’t the age difference, but the fact that she was a Czech. The Czechs were Slavs, and therefore untermenschen, sub-humans fit only for slavery or extinction. Though Hermann didn’t stop the nuptials, he made sure he did not attend the ceremony.

Finally, Hermann had to tell Albert to be more discreet because it was getting too hard to rescue him. As Albert put it, “He told me that if I wanted to protect the Jews and wanted to help them, that was my affair, but I would have to be more careful and tactful about it because I made endless difficulties for him.”

When the war finally ended in 1945, the Allies arrested Albert almost as a matter of course. Because of his family name and blood ties to the Luftwaffe chief, he would be considered guilty until proven innocent. People he had helped came forward, and he was released only to later be arrested by Czechoslovakian authorities. Once again, when it was established that Albert saved lives, he was set free.

But his release from Czech custody did not end his troubles. In fact, the stigma of being Hermann’s brother plagued him for the rest of his life. Albert was largely ostracized and barely managed to eke out a living as a writer and translator. For all his genuine heroism in the war, he had faults like any human being. A womanizer, he cheated on his Czech wife so regularly she divorced him and immigrated to Peru with their daughter Elizabeth.

Albert Göring died in 1966 in obscurity and a poverty far removed from his childhood days in his godfather’s estates. He was living mainly on a small pension, and in gratitude to his faithful housekeeper, he married her so she would get the money after he died. While Hermann Göring was the subject of many books and articles, Albert was a barely mentioned footnote.

Things began to change around 2000, when a renewed interest in his anti-Nazi activities produced several books chronicling his life and times. Unfortunately, calls for Albert Göring to be officially honored at the Israeli Yad Vashem shrine as one of the Righteous Among the Nations was rejected, at least for now. Yad Vashem cited a supposed lack of primary source documents, though they admitted Albert had a “positive attitude to Jews.”

In spite of Yad Vashem’s skepticism, the record is clear: Albert Göring actively aided victims of the Nazi regime, even at the risk of his own life. Göring, like Oskar Schindler, should be remembered as a man who took the path of courage and decency over barbarism and evil.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments