By John M. Khoury

The author is a self-described “tough kid from Brooklyn” who enlisted in the U.S. Army’s Enlisted Reserve program in October 1942, hoping to complete his college education before being called up for active duty. But the Army had other plans. At first assigned to the tank corps and then the air corps, Khoury ended up as a rifleman in L (“Love”) Company, 399th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, which saw heavy action in the Vosges Mountains of France following Operation Dragoon, the invasion of the Riviera coast in August 1944. The following is adapted from his self-published book, Love Company: 399th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, During World War II and Beyond.

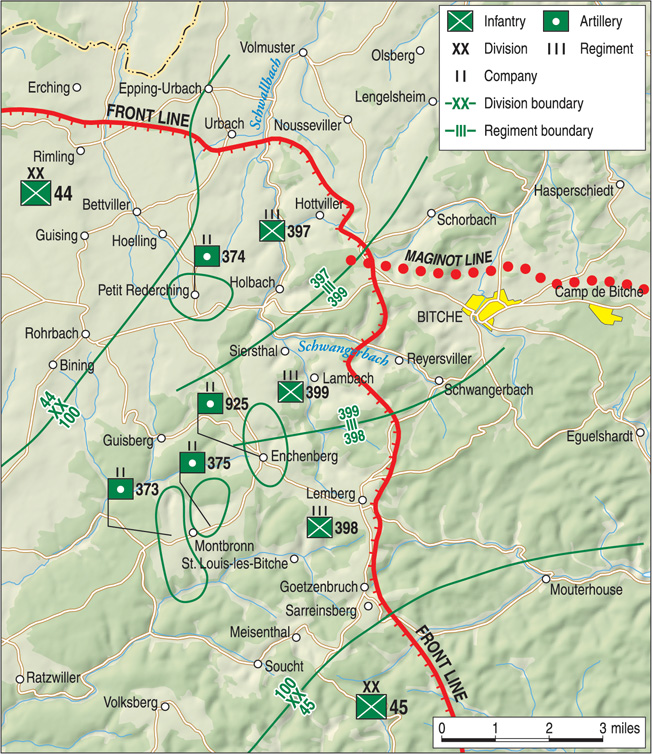

After fighting their way northward, in December 1944, Khoury and the 100th Division found themselves in Alsace-Lorraine.

“We Outfought the Germans in Almost Every Battle”

One battle faded into the next. I cannot describe every firefight with the enemy. It was almost always the same. We attacked with mortars and cannon shells followed by riflemen moving ahead with rifles, grenades, and machine guns. The Germans returned our fire with their fire. Then it depended on which side had the greater firepower and the fewest casualties to advance or retreat. Fortunately, we outfought the Germans in almost every battle. Some were very costly.

Each patrol was a repetition of the last. Whether it was a battle or a patrol, I remember the shots of German burp guns and machine guns whizzing over my head as I hugged Mother Earth. They spewed bullets in tremendous bursts. Trees and branches splintered around me as they were hit. I could only fire back with the M1 Garand rifle that I had when the Germans stopped firing for an instant or fired in another area.

When we were bombarded with artillery shells, they tore up the ground and exploded in the trees, showering us with shrapnel. They maimed and killed more men than any other weapon. The soldier had no defense against an artillery bombardment except to dig a foxhole with a cover. When you could fire back, you did it with anger and vengeance for the buddies that were hit.

hospitalized with trench foot.

After one particular battle, when everything was quiet, my foxhole buddy and I were having a meal of K rations outside our foxhole and relaxing when we were suddenly surprised. Standing before us in a spotless uniform and polished boots was a German officer. He wore an officer’s cap and not a steel helmet. He had a pistol in a holster on his belt, but he did not take it out. He said in an authoritative way that he wanted to see our commanding officer.

We were so stunned that we grabbed our rifles and pointed them at him. We took his pistol, which was a P-38 and not a prized Luger, and checked to see if he had any other weapons. He sneered at our unkempt uniforms, dirty, unshaven faces, and plodding movements. That was answered with a powerful shove that almost sent him into the muddy ground as he was escorted back to the rear. This officer was more than a lieutenant, probably a major or a colonel. We wondered how he managed to walk from his own front lines alone across no man’s land and not be noticed. He seemed to materialize out of nowhere. I did admire how he surrendered in style.

Our movements were usually on foot whether we were in reserve or were sent back up to the front line. As one company pushed through our position, we would then be following the front. We would rest a few days and then march up to push through K or I Company’s position. Until we reached their line, we would march along in the usual manner on both sides of the road with five-yard distances between each man.

The roadside sights on those marches told of the destruction of this war. There were burned-out tanks, destroyed trucks, rubble piles that were once houses, dead horses and cattle lying on their sides with their four legs sticking straight out in rigor mortis, and there were dead soldiers, too. The destruction of men and military matériel was from both sides. However, when it was an American soldier we were especially grim, and we felt a loss even though we did not know him.

We passed the body of an American sapper who was lying in the middle of the road where he had been killed by an enemy mine that he was trying to disarm. His arm was reaching into the hole where the mine was buried. It exploded, and then it was all over for him. I felt a shiver of pain, but it just added to my feeling of numbness.

“Pinky” Burress: An Unsung Hero

Upon reaching our destination where we were to attack through another company’s line, we would follow orders when to move ahead. On one particular action, we had to wait in a column in a wood and could hear the sounds of a firefight in front of us. There were American and German machine guns and rifles firing away in loud bursts. It seemed that the men ahead of us had run into strong enemy positions and were pinned down.

My platoon was in the rear of the column, and we had stopped to await orders. Out of nowhere, we were joined by a lieutenant colonel, the regimental commander, whom I had never before seen so close to the front. He stood with us for a few minutes and then shouted, “Tell those soldiers to move up! That’s an order from the colonel! Pass it along!” The command was picked up by the company noncoms and soldiers and yelled to the men farther ahead nearer the fighting. “The colonel says, ‘Move up!’ That’s an order! Pass it along!”

It was not too long after that when we received the reply from the front, “Screw the Colonel! Pass it along!” He did not stay there with us but got into his jeep and left. We, of course, did move up into the line as the situation developed and our platoon leaders gave the orders.

For the dogface at the front, the orders of his sergeant and platoon leader are the only ones he feels confident to obey because they are there with him in the middle of the fight. Very high-ranking officers are not overly respected by those at the very bottom of the military ladder unless they have proved themselves in combat.

In fact, it was rumored that the big Army brass at the top levels sent an order to the 100th Division to the effect that our casualties were not consistent with the amount of territory we were capturing. This meant that there was something wrong, that we must be having an easy time and were not pushing hard enough against the enemy.

Incidentally, long after the war was over our division commander, Maj. Gen. Withers A. Burress, was asked what he was most proud of while in combat. He said that the 100th Infantry Division conquered more enemy territory with fewer casualties than any other division in the war. For that reason alone, I think “Pinky” Burress was one of the unsung heroes of World War II.

The Platoon’s Prized Spade

[On November 28, the 399th Infantry Regiment was transported 32 miles from Moyenmoutier to Brouderdorff, France.] We arrived there after a brief rest during Thanksgiving to take our position with other companies in the 3rd Battalion of the 399th Infantry Regiment.

A story was told that a sergeant and a few of his men had come in from the front to the kitchen of regimental headquarters for a Thanksgiving dinner. They were on special assignment to have this special treat. Of course, they were in miserable shape, dirty and smelly, and they were greeted by an arrogant mess sergeant who said to them, “You’re too late. The kitchen’s closed. There’s no more turkey.”

This did not please the hungry sergeant and his men. They took their rifles off their shoulders and pointed them at the mess sergeant and his cooks. “We have just come in from killing the Germans! Now, do we get a dinner or do we have to shoot somebody?” They were promptly fed.

[On December 2, the regiment was trucked to Siewiller, 16 miles from Brouderdorff.] From this point we advanced on foot. Many of the towns in this part of France, which is Alsace, have German names and the people speak German and French, but they are true Frenchmen. For the next few days, we met little resistance because the Germans had retreated. Nevertheless, we had to dig in each day because of sporadic enemy shelling.

One day while we were marching, we passed a few tanks of the 781st Tank Battalion, which were attached to our division. We noticed all the extra items they were able to carry on the outside of their tanks. They had cartons of “10-in-1” rations that contained cans of orange marmalade, bacon, and meat and loaves of real bread and butter.

As we marched by the tanks, we liberated as much as we could without the tankers’ knowledge. One of best items that we carried off was a full-sized shovel. That shovel was used to dig a foxhole in a quarter of the time it took with our regular entrenching tool. When we had to dig in, this shovel made it almost a pleasure. Later, it was passed around to everyone in the platoon. That spade was carefully guarded, but one day it mysteriously disappeared. We never caught the culprit.

A Case of Friendly Fire

[For the next several days, the regiment continued marching until it reached the vicinity of Goetzenbruck, France.] We were ordered to dig in along the crest of a hill. I had selected a spot for our foxhole, but my buddy who was to be in the hole with me did not like my choice and started digging about 50 feet to the left. I did not argue because one spot was the same as any other.

We had been hacking at the frozen earth for a short time when, suddenly, we were being pounded with artillery shells. Both of us dove into the partly hollowed-out foxhole as the earth around us shook with the explosions. Dirt and shrapnel flew up and around us. This lasted for about 15 minutes as I tried to crawl as deeply as possible into my helmet for protection.

Finally, all was quiet and we came up to see what had happened. The spot I had chosen for a foxhole had a direct hit! A thing like that unsettles the nerves and brings on a prayer of thanks.

The shelling did not sound like German 88mm artillery, and someone said that one of our officers had read the contour map wrong. He gave the number of the hill we were on and called for artillery fire instead of the number of the hill in front of us, where the enemy was dug in. Not only were the Germans trying to kill me, but I had to worry about my own officers! I don’t know what casualties we had that time, but every day someone got sick or was wounded or killed.

The Battle For Lemberg

[On December 8, the unit was at Lemberg, France.] This small town in the Vosges Mountains is an important intersection for main roads and a railroad leading in all directions. The strongest forts in the Maginot Line were located at Bitche, which is only about five miles to the northeast. The Germans retreated to this town and set up strong defenses to hold it against our advance.

On December 9, early in the morning, the 3rd Platoon moved through the woods following a road leading to a railroad trestle. We reached the edge of the woods and were deployed along a draw facing an open field that sloped upward toward the railroad embankment; the road to our left ran under the trestle. We peeked over the edge of the draw and looked across the open field, but we could not tell what the enemy had facing us. All the dogfaces were tense as they fixed bayonets.

At that time I had a Springfield ‘03 rifle and a grenade launcher and two rifle grenades. We awaited the command to charge across the open field into the German positions. Our mortars and artillery did not lay in a barrage before us. The attack was supposed to be a surprise. Smoke shells were probably used to screen our movements, but they did not do much good.

When our platoon leader, Lieutenant Bennett Taylor, gave the order to charge, “Let’s go!” it was like a reenactment of a World War I movie. We all rose up and started running across the open field. We had not gone very far when the Germans opened up with their machine guns, rifles, mortar shells, and 20mm antiaircraft gun at us with tracers and exploding shells.

There was booming noise and smoke and streaking bullets whizzing all around us. I had the strangest feeling that I was not really there in the middle of all this mayhem. In my mind, I was floating as I was running straight for the cover of the embankment, and I did not feel any terror or exhaustion. It was not me, but someone else who was there, and I was just an observer. I didn’t even seem to hear or smell the battle. It was like a dream. Some would call it an “out-of-body experience.”

In what seemed like an instant, I ran across the open field, straight into the enemy fire, cut to the road just to the left of the underpass, and hit down on the side of the embankment.

Meanwhile, right over our heads, the Germans were firing away with a machine gun and the 20mm cannon. I crawled up over the embankment to see where they were and caught sight of the position. I crawled back behind the embankment, removed my bayonet, and attached the grenade launcher to the end of my rifle. Carefully, I aimed for the spot just beyond the tracks and to the left of my position where I had seen their emplacement. I fired the two grenades, and in the turmoil I don’t know if they hit the target, but there was no more firing from there.

This attack was recorded in the Story of the 399th Infantry Regiment––the regimental history: “Love Company spearheaded the 399th into Lemberg, when they made a dash from the eastern woods to reach the railroad underpass in the center of town in midafternoon. The railroad was the Germans’ main line of resistance.

“Lt. Taylor’s 3rd Platoon reached the railroad embankment and Lt. MacDonald’s 2nd Platoon dashed up a draw to hit the railroad on the right. Charley Goldman stuck his head over the embankment and got hit by a machine-gun bullet. Sgt. John Butler tried to lead the 2nd across the tracks but didn’t make it. They were firing a hail of 20mm stuff and machine guns up and down the tracks. The only possible way into Lemberg was through that underpass and the Germans knew it.

“A bunch of krauts came charging through the underpass and we wiped ‘em out with guns and grenades––Harvey Rohde, Al Lapa, and Bob Binkley shot up plenty. George Demopoulos of the Medics amputated a Mike [Company] boy’s arm under fire. Then two mortars were rushed up behind the embankment and set up like infantry crossfires, each firing a different direction. John Khoury crawled up on the tracks and directed fire to knock out a flak wagon and a machine gun. Then we opened up with everything we had, charged through the underpass, and made a dash for the first couple houses of Lemberg.”

Fighting House-to-House

There was enemy small-arms fire as we sought cover inside a house that had thick masonry walls. They were shooting at the windows and the door from positions overlooking the main street opposite us. Private Carroll Stratmann had just joined the company as a replacement on November 26. Two weeks later, as he stood next to me at the door of that house, a sniper’s bullet hit him.

I crouched by a window and looked up at the German position and was surprised to see it in plain view on a low hill. Then an officer or noncom walked upright in front of the dug-in soldiers and was silhouetted against the sky, apparently giving orders to his men. He was about 200 yards away, and I took careful aim from the window, fired one shot, and missed. He did not flinch or duck or take cover.

I fired a second shot that did not miss. He stopped and collapsed backward. That was my small contribution to the memory of Stratmann, who later died of his wounds.

Meanwhile, in a house at the end of the main street, there was a German sniper firing from the upper window at any GI in the street. A Sherman tank was called in and it sent one 75mm cannon shell into the window, which eliminated the sniper but did not improve the house.

Lemberg was taken after some house-to-house fighting, and the enemy retreated to fight at his next line of defense.

According to the Morning Reports of December 8, there were six officers and 150 enlisted men in Love Company; two days later there were five officers and 139 enlisted men.

Of course, news circulated fast of who was wounded or killed or missing. That news always hurt everyone. On that day, word came that “Redbird” [Pfc. John W. Howe, Jr.] was hit and taken to a house nearby where our medic was giving him first aid. A couple of old buddies stopped in to see him and reported back that Redbird sent a message that he was okay and would be back soon.

But he had been hit by shrapnel in several places, and his wounds were so severe that he did not survive. I felt both sad and angry because he was such a good old buddy.

For their action at the railway bridge on December 9, the soldiers of the 3rd Platoon were awarded Bronze Star medals for valor.

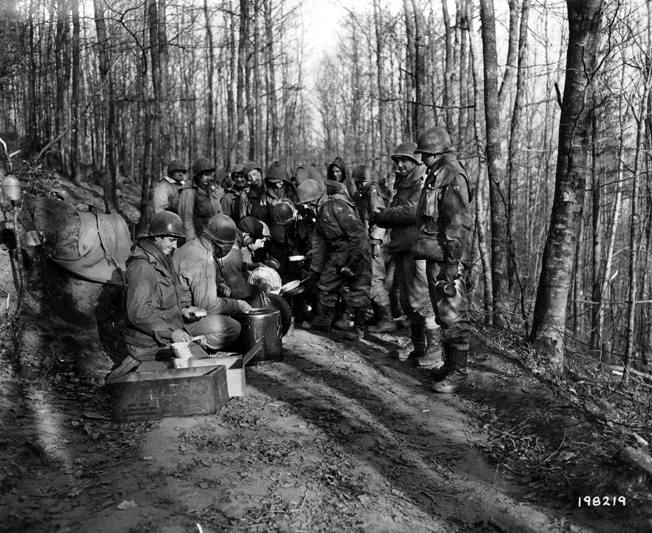

The Company in Reserve

During the next week, the company was in reserve. We bathed out of our helmets, which served as wash basins. We also shaved a two-week growth of whiskers with a dull Army razor. I let my mustache grow just for a change. We scrubbed our clothes of the mud and filth. The supply sergeant gave each of us clean underwear and socks.

We stripped, cleaned, and oiled our weapons to be sure that they would be ready for us when we returned to the front. Our rifle, BAR, or carbine was our closest friend.

Meanwhile, laid out in contorted positions in town were the bodies of about a dozen German soldiers that we passed on our way to chow each day. Seeing the gray, lifeless corpses with sightless eyes wide open and flies buzzing around them did not disturb most of the men who had seen almost two months of combat and death in many forms. Since it was late autumn and the weather was cold, the corpses did not smell of decay.

During this week, we also heard about the German Ardennes Offensive that became known as the “Battle of the Bulge.” We were not involved directly in the battle, which was to the north of us on the Belgian and Luxembourg front. The situation there was very serious. Our part of the front in the south with the Seventh Army was of secondary importance.

Support units, such as tank battalions, artillery batteries, and Army Air Corps units were relocated to the Ardennes sector where they were needed. As a result, there was a notable lack of new replacements in our company. Since we entered combat at the beginning of November, the Morning Reports showed that we had 18 privates and one T5 join the company as new replacements. Many came from other units where they were no longer needed, such as antiaircraft artillery, and others came directly from the States right out of basic training. Nevertheless, there was a constant shortage of soldiers in our company.

I had a chance to look around at the whole company while we were in reserve. It was obvious that there were many men gone from the company, and the ranks of non-coms were filled with the promotion of Pfcs and privates. At the time I did not know how many were in the company but the Morning Report of that day listed five officers and 123 enlisted men.

A memorable soldier was T. Sgt. Argil H. Warner, who was a platoon sergeant and probably the oldest man in our company. He was about 34 years old and was affectionately called “Pop” Warner by “his boys,” who were about half his age. His younger brother, who was in the 1st Infantry Division, had urged him to transfer out of the rifle company and get an assignment in a less dangerous unit. Because of his age he could have gotten another assignment but he replied that he would not leave his boys.

In the vicinity of Schwangerbach, France, Warner was killed by a direct artillery hit on his foxhole. He wanted to do his duty as a soldier even if it cost him his life. The Army does not give medals for devotion to duty.

The Unbreakable Maginot Line

On December 15, we reached a wooded mountain facing the Citadel and the Maginot Line at the town of Bitche. (The French pronunciation is “Beesh,” but for several reasons the Americans called it a female dog.)

From the edge of the forest, we could look across an open field of some 500 yards toward huge concrete forts where the retreating German Army had taken up defensive positions. From our foxholes in the woods where we had dug in, we had no idea what we were facing. We could see concrete bunkers that had a commanding view of the entire area before them.

The fortifications here were the strongest of the entire Maginot Line. We did not know that. We only knew that this was the next objective. Looking at these gray, ominous forts did not make us feel very happy. We waited for orders to attack, but the enemy positions had to be softened up first.

[Thirty-six hours of “softening up” was undertaken by air and artillery on the forts surrounding Bitche.] Our artillery pounded the forts with a barrage of shells. We could see the shells land and, when the air cleared, the forts had chipped concrete but were still intact. The division artillery battalion with 155mm “Long Tom” cannons was brought up to fire point blank at the forts. They had direct hits, but it was the same as before. We could see some shells bounce off the rounded concrete bunkers and burst in the air.

Finally, some of the heaviest artillery in the Army was brought in, and that included the 240mm howitzer. Seven Germans surrendered after being pounded by these shells. They were driven out by the concussion and the noise, but the shelling did very little damage to the forts.

Then 78 fighter bombers were called in, and they dropped 27 tons of 500-pound bombs in a series of dive bombings in a futile attempt to neutralize and destroy their targets. After all this, the forts were still there: gray, silent, unmoved, looking benign, but deadly powerful.

A Planned Assault by Infantry

We now knew that it was up to us to take those forts where the Germans were still hunkered down and waiting. For us, the expendable GIs, it was a matter of getting up to the open gun slits and the steel doors and fighting our way in to rout the enemy. The plan was for us to charge across the open field under covering machine gun and mortar fire with a smoke screen to reach the fortifications.

At this point, each soldier was to carry out his own assignment. I had the task of carrying a satchel or “beehive” charge—a 25-pound, cone-shaped charge of TNT designed to cling to a vertical or horizontal surface. This had to be strategically placed by hand, and the fuse had to be ignited. Before it exploded, I would have enough time to find a cozy spot to wait in safety.

This whole idea seemed ludicrous to me after seeing what little damage had been done before by huge pieces of Army ordnance. However, I was assured that this little device was shaped to explode with such tremendous, concentrated force that it would blow a hole in any spot. Through the opening, we could then drop lots of grenades on the defenders.

Still, to me, the idea of running across that open field of fire, carrying this clumsy bomb, climbing up to a huge bunker, and setting it off seemed to be the height of absurdity. However, I knew I would try to do it. On other missions, I had known fear but I had not lost courage or determination. This time I had a mortal fear that it would be my last mission.

Other men in the platoon had other assignments. One of them, Al Lapa, had to carry a flamethrower across the open field and try to get up to an opening in the bunker. Then he had to shoot his fiery stream inside at the enemy. He told me, “They must be crazy if they think I’m going to run at the Krauts with 10 gallons of gasoline on my back! It weighs 75 pounds and when I hit the ground the thing knocks off my helmet and slides off my back.”

When he complained to Lieutenant Taylor, someone else got the assignment. These Maginot Line forts were so solidly built that they could only be taken from an inside assault. Fortunately, other units of the division were able to blast in through the steel doors to rout the German defenders in their sector. Before we had to attack the fort in front of us, the situation was changed by the battle to our north.

This situation convinced me that bombing and strafing and artillery shells alone cannot win battles and in turn cannot win wars. Even 70-ton tanks cannot do it alone. It is the little soldiers in the front line who must be there to claim the victory or suffer the defeat. All the other units have to support them so that they can take possession of the enemy’s territory and defeat his forces.

Lost in the Woods

Our assault on Bitche was aborted because the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, was drawing on all the Allied military resources; we could not continue our advance without support.

[On December 21, the regiment marched four miles to Lambach.] It was time to return to the front line and relieve King Company. 6:15 pm is late in the evening to start a march and, in winter, in the snow-covered mountains where there is no light but the moon and the stars, the world is shades of gray.

No one had any idea of where we were or where we were going. In order not to get lost, we followed closely behind the soldier in front of us, and no one could talk or light a match or cigarette. It was single file through woods, across roads and open fields, and at one point we slid down the bank of a stream on the seats of our pants and waded across to the other side. There the river bank was muddy, and we slipped trying to get up it. The man behind had to boost up the man in front of him. Most of the time each soldier had to hold onto the belt of the man in front of him because it was pitch black. We were lost!

Somehow, the next night we finally arrived at Lambach and spent the night in the schoolhouse. We had gone four miles in 22 hours! We never found K Company but it was rumored that we had gone behind the German line and circled back to our own. It seemed that map reading was not a strong point with some of our officers.

The following morning, the battalion commander, Major Angelo Pinero, arrived on the scene and reamed out our company commander, Captain Carl Alfonso, for getting lost. We were grateful that we were still alive.

Relieving K Company

We still had to relieve K Company and headed off in daylight to find them. We came across a distant spot on the side of a hill that looked like an outpost in front of a wooded area. Lieutenant Taylor halted the platoon in the woods where we were and ordered another GI and me to go and check the outpost for K Company.

We slowly plodded up the snow-covered hill with our heavy winter clothing, our clumsy shoe-pac boots, our rifle, and ammunition, slipping every few steps. We were about 200 yards from the outpost and still could not tell if we were looking at friends or enemies. Then we saw two helmeted heads rise slowly and two rifles appear over the edge of the foxhole. They were pointed at us! Uh-oh! In an instant, we both spun around and raced back down the hill as bullets flew at us. We fell. We rolled. We zigzagged and got back gasping to our line.

Before we moved on, a 60mm mortar crew from our heavy weapons platoon was called in to return fire to that outpost. As we watched, they sent up three or four shells that landed directly on the enemy dugout. The accuracy of our mortarmen amazed us. That finished their outpost.

We finally found K Company and took over their foxholes so that they could get relief and rest for a few days. During those times when we passed through another company hardly more than a few words were ever exchanged. It seems as though one company had gotten a reprieve and the other company had been returned to serve its time. Between the two groups, there were only feelings of common understanding of what we all experienced.

Christmas on the Frontline

[On Christmas Eve, the regiment was trucked 82 miles back to Goetzenbruck.] Christmas 1944 was spent in a foxhole. We had to dig through snow and a foot of frozen ground before we reached softer earth. We cut pine branches to line the dirt floor, and heavier branches were cut to cover half of the opening of the hole. This made a cozy place that gave protection and warmth.

We had a special hot turkey dinner on Christmas Day, which was received on a chow line about 300 yards behind the front line. The extra treat was a can of beer and some peanuts, and the special present was a fur-lined parka overcoat. The fur was on the inside and the rough skin was on the outside. It had a reversible cloth covering in white on one side and khaki on the other. With the attached hood, we were warm inside that coat like never before. This made everybody look very wide, but underneath there was just some skinny kid.

It was relatively quiet that day. Some cannon fire was heard now and then, but it was very little. What a paradox it was to be eating out in the snow with grubby, grimy hands, sitting on a log, enjoying turkey, mashed potatoes with gravy, and a hot cup of coffee and saying “Merry Christmas.”

The religious services were brief and held in the open field just beyond the chow line and led by a chaplain who seldom ventured to the front on any other occasion. Nevertheless, Christmas carols were sung, and it almost seemed festive. When it was over, we picked up our weapons and shuffled back to our foxholes.

We remembered how it was often said that the war would be over by Christmas. There was a popular song, “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” We were not home and there was a lot more war to be fought before it was over. On December 26 we moved again––back to Lemberg, less than two miles away.

On the Defense

For the first time since we entered the line, we had to take up defensive positions. We no longer were chasing the Germans. We were going to wait for them to attack us, but that still meant that we had to send out reconnaissance patrols. We needed to learn where they were, what they had, and what they were doing.

We also cleaned and checked our weapons. Every man was given extra ammunition and grenades. Fifty-caliber machine guns, which are usually mounted on vehicles such as a tank, half-track, or a truck, were brought to the front-line positions with ample belts of ammunition. We were well armed to defend our line.

The main deficiency in L Company was the lack of men. We had between 125 and 130 enlisted men and six officers. Of the original number of 141 privates and Pfcs, there were only about 94 at the end of December 1944. Losses of privates and Pfcs were filled by replacements, and we had very few of them for many weeks. Sergeants were always replaced by privates or Pfcs, so that there was always a full complement of non-coms. I was asked to be the leader of my squad at this time.

To be a sergeant was not one of my burning ambitions, and I demurred. However, when I was told that it would be either me or another soldier whom I did not think was experienced, I accepted. Thus, I was an acting sergeant and my “12-man squad” consisted of one soldier, Private Junior P. Ogle. We were not a formidable force, but we were ready.

We had the responsibility of defending a very wide stretch of the front. Foxholes were manned by two men, not three, and they were spaced about 100 feet apart. Each hole was placed to cover an open field of fire from a ridge that was to the left of the railroad tracks. We had never had such a large front to defend. If just one foxhole was penetrated, there was enough room to send an enemy company through, and we had nobody behind us in reserve in case we could not hold the line.

Forward outposts were about 50 yards in front of this main line of defense. One was to the left in an open area, and the other was to the right of the railroad tracks. Each outpost was manned by two men.

For a couple of days, we had nothing to do but prepare and wait. We were not sure when and if the Germans were going to attack. We thought that this was a time to rest while the Battle of the Bulge was being waged in the north.

Operation Nordwind: A New Years Day Surprise

We did not have anything to drink to celebrate the coming New Year. Alcohol was never issued to the men in the infantry. However, for this New Year’s Eve, one bottle of beer was given to each of us.

Late in the evening of December 31, 1944, a lot of activity on the German side of the front was noticed by our forward outposts. We were not sleepy because we had been expecting some kind of attack, but we did not know how big it would be. Strangely, no one seemed to be nervous or panicky. There was just a tense calm along our line as we waited in the icy cold, exhaling clouds of vaporized breath, and moving feet and hands to keep warm. The moon was bright and the snow reflected the light, which gave an eerie grayness across the land.

It was in the early hours of New Year’s Eve when the Germans launched their attack on the Seventh Army front. Hitler called it “Operation Nordwind.” Our forward outposts were hit hard by the Germans. Lapa fired the three rounds from the bazooka he had out of the right outpost and then kept firing his BAR until he had to retreat to our main line of defense.

Ernie Weinberger was hit with a bullet that pierced his cheek and mouth and exited his other cheek. Paul “Abe” Lincoln in the left outpost was also firing his BAR when they were hit. He was in a dazed state of shock when he saw his buddy, Mo Lloyd, shot through the head with blood and brains spilling out of the wound. Lincoln made it back to our line and was immediately sent back to the battalion aid station with Weinberger.

On our main line of defense we heard the firing of burp guns and rifles. We saw our men from the outposts running back to us, and we were ready. No one was asleep or drunk, as the enemy expected us to be on New Year’s Eve. The Germans were yelling and screaming as they ran toward our line of foxholes, calling us all kinds of names like “dirty American bastards,” but we did not mind the insults. It was the least of our worries.

Immediately, we fired a tremendous fusillade of machine-gun and rifle fire. I got out of my foxhole and crouched behind a tree to be able to see better and move easily. I fired at the gray shadows with my M1 without taking time to slowly aim and squeeze off each round. There were so many of them coming toward us that it was more important to fire as rapidly as possible. Furthermore, it is almost impossible to see the sights on a rifle at night; careful aiming was hopeless and a waste of time.

The firing from our line was furious and harrowing. We kept shooting and shooting and shooting. It seemed to last for hours. The Germans were drunk with schnapps and gave us very little return fire. It was hard for them to yell curses at us and fire their bolt-action Mauser rifles or their machine pistols accurately while running at us.

I don’t know how many enemy soldiers were hit in front of us, but I know that their attack was broken. They stopped charging and moved off to our right flank. We had held fast on our line, and it became quiet after a few hours. There was sporadic small-arms gunfire and artillery shelling during the following day as we stayed in our positions.

Green Replacements

Late in the evening of January 2, 1945, a task force from the 63rd Infantry Division was sent up to take over our positions in Lemberg. It was dark, of course, and difficult for the new troops to orient themselves in this new location. They appeared clean-shaven with spotless uniforms and weapons. They were advance units of their division that had arrived at the Vosges Mountains front in defensive positions on December 22. We placed them in our foxholes and told them “Good luck!”

One of them who was probably 18 and just out of high school turned to me, trembling, and asked, “Where are they?” I pointed toward the enemy line and said, “They are over there about 200 yards in front.” He trembled as he looked at me and sobbed quietly. There was nothing more I could say.

Later, I thought about these green, young boys sent to the front to relieve us grimy, tough, veteran dogfaces. We were all about the same age. What could I say to them? Don’t worry. You’ll be all right. It’s only a war. Nobody gets wounded or killed. That’s just noise you hear. In a little while you’ll go home to your mother. Perhaps, I should have told them the philosophy of old dogfaces like me: You’ve got to kill or be killed!

After two months of seeing death and destruction, I was tired of it and I felt like a very old man. I had thought for some time that the war was never going to end. Thanksgiving and Christmas and New Year’s Day had come and gone, and there was no end in sight. What was the use of fighting? We had been living in the rain and snow during one of the coldest winters in recent European history. We shivered as we trudged out on patrols, and we never felt warm. Death would not have been a bad alternative. I did not tell my thoughts to any of my buddies. Besides, we had to move out to our next battle, and I had to forget such a stupid idea.

Pfc. Maurice E. Lloyd, MIA

The front line on the Seventh Army front was skewed badly after the Nordwind offensive. The 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, which had been put into the line on the right flank of the 100th Infantry Division, fell back five miles when the attack came. Our Love Company held the right flank of the division line, which was now exposed and undefended. The 44th Infantry Division on our division’s left flank also fell back from their defensive positions. This left our division with two vulnerable, exposed flanks, because we had held fast along most of our front.

Units of the division were moved back to straighten the line. There was a lot of movement on our side to reorganize our positions. In addition, we had to fight the enemy, who was keeping up his attack with artillery and infantry assaults. There was no time to relax and leisurely establish an orderly front.

We moved to Enchenberg on January 2. We had lost many men; among the missing was Pfc. Maurice E. Lloyd. He was never listed as killed in action because his body was not found until 30 years later. His foxhole buddy, Pfc. Paul “Abe” Lincoln, knew he had been killed but unless a body is found a soldier is listed as MIA.

Lloyd’s name was engraved on the Wall of the Missing at the American Military Cemetery in Epinal, France. At the time the cemetery was planned and completed, it was thought that all the bodies of American soldiers who had been killed had been collected and buried or shipped back to the States.

In the 1970s, a man, his son, and their dog were tracking through the woods outside Lemberg when the dog led them to a log-covered dugout where they found the skeletal remains of a soldier. Wearing the uniform of an American soldier and still holding the automatic rifle he died with were the remains of Pfc. Maurice E. Lloyd. When he was killed, he probably never knew what had hit him. His identity was confirmed by his dogtags and a religious medal inscribed by his girlfriend, “With Love to Mo from Billye.”

When his bones were removed for burial, the mayor and citizens of Lemberg paid homage to him in a special ceremony. Later, at a memorial service, his family participated in a ceremony at the American Military Cemetery in the Ardennes, where he was finally laid to rest. A monument was made by the people of Lemberg and placed at his foxhole––the only such dedication of a foxhole in the entire war.

Trench Foot

Many men were going on sick call because of trench foot, which is a form of frostbite. This can result from not taking off combat boots, letting the feet dry in the air, and changing into dry socks. So many soldiers were getting trench foot that we heard that the big brass in the rear echelons threatened to court-martial soldiers who went on sick call with trench foot.

They must have thought that that was a brilliant idea, but who would be left to man the front lines? Certainly, a sick and miserable GI at the front could use a court-martial to ease his suffering. If he was a private, what could he lose in rank and pay? How unhappy would he be in a stockade, miles from the front and served hot food and given a clean bed and a roof over his head? It would have been almost as welcome as a million-dollar wound.

In reality, no one was even threatened with a court-martial because it was extremely difficult to prevent trench foot when you were always on the move with the enemy just a few hundred yards in front of you. Seldom did you take off your boots and change your socks if you even had a dry pair because you never knew when you had to move out. It snowed and rained, and nothing you wore was dry. If you took off your boots, you could not easily get them back on because your feet were swollen. At night, you slept a few hours at a time in your foxhole with your boots on and with your weapon at your side.

[Khoury’s war was soon over. He came down with frostbitten feet and was evacuated to a military hospital in the town of Vittel, famous for its mineral water. He had mixed feelings about this because he did not think his injury was serious enough and did not want to leave his buddies.]

On the way to the hospital, I saw others who had wounds and ailments that were much worse than mine. I could walk while some men were on stretchers. I looked fine, while others had bandages. I could talk, while others mumbled incoherently. I was just too healthy.

[But Khoury was hospitalized for many weeks. During that time, he gained enormous respect for the nurses who tended the sick, wounded, and dying.] They worked long hours and saved so many lives that the doctors owed much of their success to these women. The men—the patients—also knew that it was the Army nurses who were always there when they needed them.

The author is offering signed copies of his self-published book, Love Company, for $18.00 each plus $4.00 postage. Write him at: John M. Khoury, 20 Blanch Avenue E107, Harrington Park, NJ 07640.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments