By Arnold Blumberg

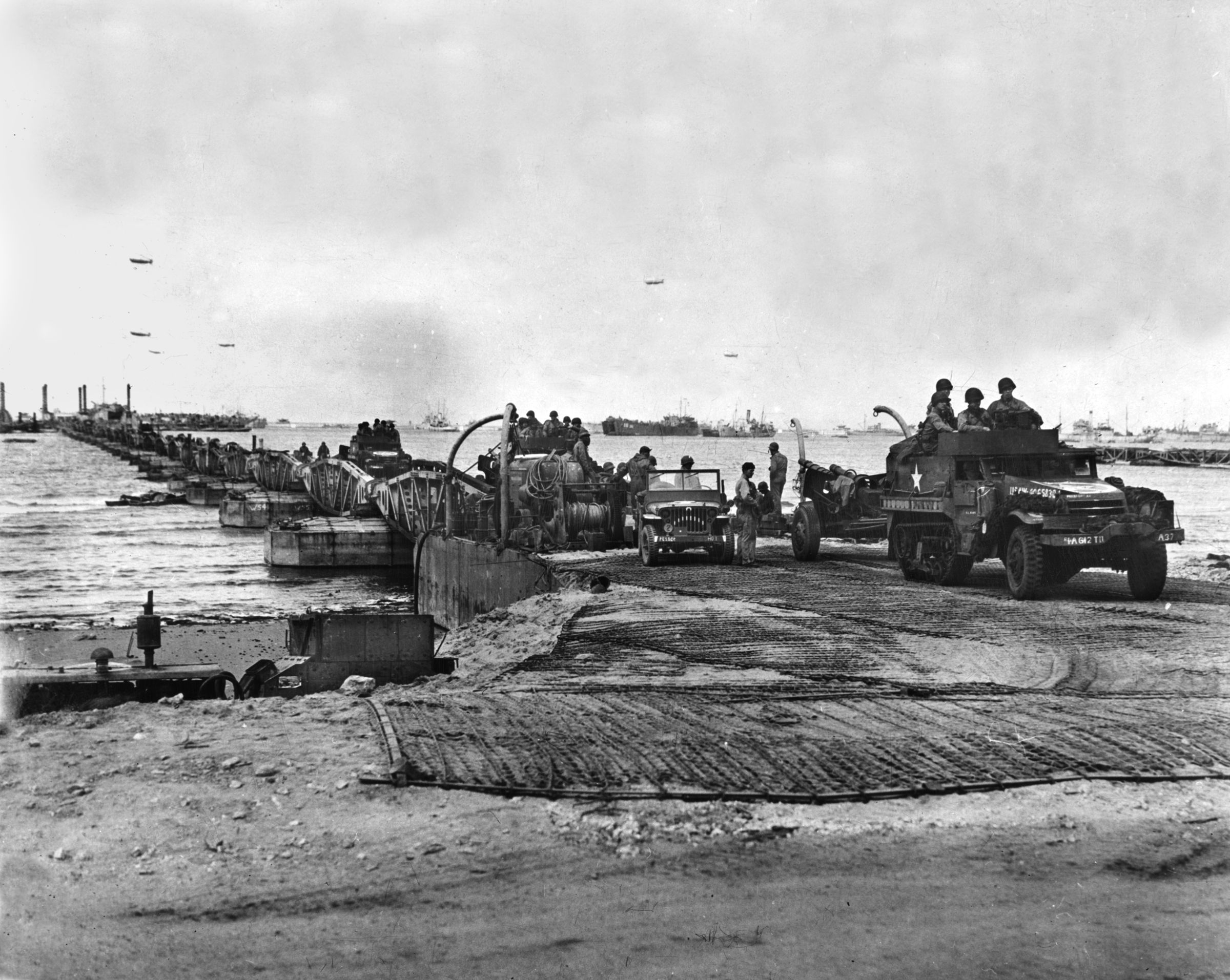

After four months and a 600-mile advance from the beaches of Normandy into Brittany and then through eastern France, the spearhead of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s U.S. Third Army, the 4th Armored Division, closed on the western boundary of the Third Reich. The final drive for the German frontier had begun on November 10, 1944, from the 4th Armored staging area east of the French city of Nancy.

For nearly a month, the unit, under Maj. Gen. John S. Wood, who was replaced by Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey on December 3, lumbered forward fighting over difficult terrain with little friendly air-ground support due to overcast skies and constant rain. American vehicles were confined to the few good roads in the region by soaked ground that transformed the area’s pastures into bogs. As a result, the highway-bound American tanks suffered delays and casualties from German antitank guns, shoulder-fired panzerfausts, and mines.

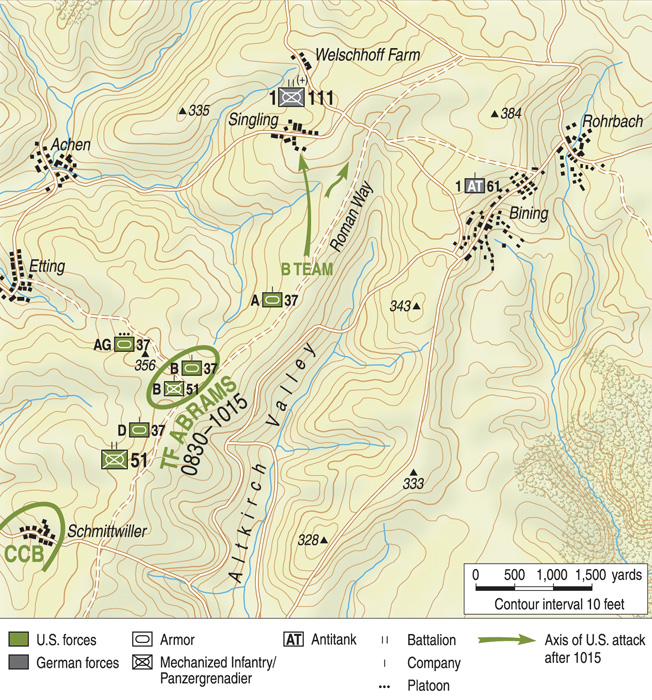

On December 2, Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy, commander of XII Corps, Third Army, requested of General Patton that 4th Armored, gathered just east of the city of Sarre-Union, be pulled off the line for much needed rest and maintenance. Permission was granted by Army headquarters but not before the unit was ordered to make one last push for the German border a mere 20 miles away. The objectives of this last advance were the important rail center town of Rohrbach-les-Bitche and the village of Bining which controlled the southern approaches to Rohrbach-les-Bitche. Not initially taken into account when the move on Rohrbach-les-Bitche and Bining was planned was the small village of Singling, two miles west of the American objectives.

Singling and the Maginot Line

Singling, situated on a southwest-northeast ridge, was an agricultural settlement of 50 squat stone houses strung along a half mile of narrow road running from Achen, near the Sarre River, east to Rohrbach-les-Bitche and Germany. Around the church, brown stone school house, and market square were clustered concrete and stone houses painted white, red, yellow, blue, and pink with red tile roofs. Stables fronted the main street. Some of the farmhouses were almost fortress-like with three-foot reinforced concrete walls and gardens surrounded by more high, thick walls.

Concrete pillboxes stood at the eastern and western entrances to the village, on the hills and in the valley to the north, and on the ridgeline to the south. As part of the French Maginot Line, the area was a key position in that line’s secondary system of forts and thus was well placed as a forward strongpoint against attacks coming from the southwest aimed at Rohrbach-les-Bitche and Bining.

As the attacking U.S. troops soon learned, operations against the last two towns could not be separated from those against Singling. The main avenue running into the Rohrbach/Bining area from the south followed high ground along the west ridge of the valley, passing by a small series of knolls that could provide positions from which enemy antitank fire could be brought down on any attacking force.

of both American and German units had to contend during the fighting in eastern Lorraine. The Americans ran into unexpectedly tough resistance as they neared the German frontier in early December 1944.

One way to bypass the road was to follow the trace of an old Roman road along the reverse slope of the ridge west of the valley. However, the west side of the slope could be brought under direct fire from Singling, which, due to its location on the slightly higher ground and placement on the curve of the ridge, commanded this approach route for three miles to the south.

Neither route was, therefore, satisfactory since advancing troops would be under German observation before they were within attacking range, but the avenue to the west side of the ridge seemed to offer the best hope for success. Yet, if it was to be used to go after Bining the Americans would first have to neutralize Singling, and that would be a problem because the hamlet was dominated by a ridgeline 1,200 yards to its north.

The extent of the obstacle Singling presented to 4th Armored’s advance toward Rohrbach and Bining was driven home on December 5, 1944. That morning the commander of the 37th Tank Battalion, Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division, Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams, received his instructions for the day’s operation directly from division headquarters. The orders directed Abrams’s unit, after Combat Commands A and B secured the high ground across the river south of Dehlingen (about six miles south of Rohrbach-les-Bitche), to “push through and continue northward with Rohrbach-les-Bitche as its objective.”

Taking Enemy Fire from Singling

As the colonel reviewed the mission, he wondered why his tankers would be going into combat without the usual infantry support. Up to that time the campaign in Lorraine saw the 4th Armored Division operate in small, flexible task forces, each consisting of one or more tank companies supported by at least one company of armored infantry. These combat teams were formed on an ad hoc basis to deal with enemy strongpoints, clear resistance in urban areas, give the tanks infantry guides to navigate safely in villages and towns, or hold ground against counterattacks. Advancing without foot support would make it difficult to take and hold ground and would leave vehicles vulnerable to enemy antitank weapons. Fully cognizant that sending a tank battalion out on its own against an opponent of unknown strength was far from normal divisional operating procedure, Abrams nevertheless made no complaint and readied his battalion for its new assignment.

Around noon on December 5, Abrams sent the 14 M4 Sherman medium tanks of C Company, 37th Tank Battalion northeast on the road to Bining. The M7 Priest self-propelled guns of Batteries B and C, 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, 4th Armored Division, sporting 105mm howitzers, provided direct fire support for the move, while Battery A of the 94th laid down a smoke screen to disrupt any enemy fire coming from Singling on the American left flank.

Soon after the U.S. tankers started to roll over the open fields toward Bining, accurate antitank and artillery salvos hit the armored column. The enemy missiles came from Singling and the high ground northeast of the village. In short order all of C Company’s tanks were put out of commission by the rain of enemy projectiles or became stuck fast in thick mud. The tank crews abandoned their vehicles and raced back to friendly lines on foot. As the day ended, Abrams withdrew the balance of his command beyond the sight of the offending German guns and planned the resumption of his assignment the next day.

On the night of December 5, the 37th Tank Battalion leader received his orders for the next day. As expected, he was ordered to drive for Bining. Fortunately, this new attempt would be supported by the division’s 51st Armored Infantry Battalion and two platoons from Company B, 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion with M18 Hellcat tank destroyers. With his acknowledgement of his new orders, Abrams requested support from at least six artillery battalions to smother Singling with such intense suppressive fire that the enemy could not interfere with the American move on Bining.

Early on December 6, the engines of the 37th Battalion tanks roared to life as Task Force Abrams’s “B Team,” the 14 Shermans of Company B, 37th Tank Battalion, including five with the new 76mm high-velocity gun, and the 57 infantrymen of Company B, 51st Armored Infantry Battalion prepared to move out. Because of the muddy ground, the armored infantry’s usual mode of transport, M3 Halftracks, could not keep up with the tanks. Consequently, the foot sloggers were ordered to mount up on the tanks for their ride into battle. As B Team assembled, the Shermans of Company A, 37th Tank Battalion took a position one mile ahead of the rest of the American force.

As the U.S. tanks prepared to go forward, the guns of the 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, in conjunction with those of the 704th tank destroyers, placed accurate high-explosive and smoke rounds on the Germans around Singling. The requested fire support from the six artillery battalions Abrams so very much wanted never materialized. After an hour attempting to suppress the fire coming from Singling, during which time the tanks of the 37th added their shells to the effort, Abrams suspended the effort to work out a new plan to get his move on Bining started.

The Methodical Advance on Singling

Abrams determined that Singling had to be neutralized before any successful attack on Bining could be mounted. To that end, he directed B Team to swing west and take the town from the south. After Singling was secured, he would unleash the balance of his task force, Company D, 37th Tank Battalion, the 25th Armored Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, and the attached 1st Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division, on Bining.

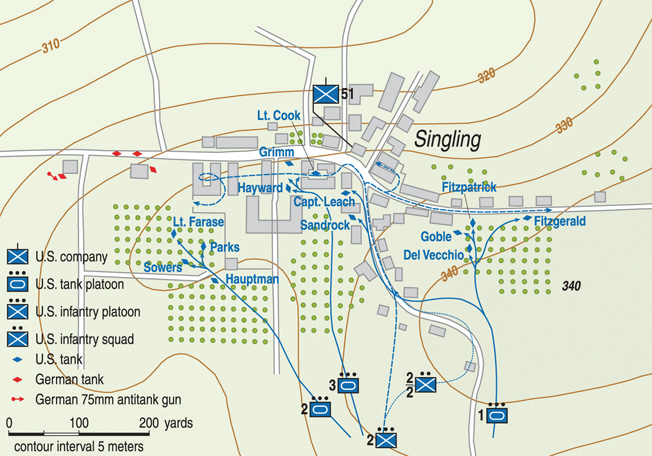

To break the continuing stalemate, Abrams ordered the commander of his Company B tanks, Captain James C. Leach, to drive straight for the southern edge of Singling with B Company’s 2nd Tank Platoon, led by Lieutenant William F. Goble, on the left; 1st Tank Platoon, under Lieutenant James N. Farese, on the right; and the 3rd Tank Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Robert M. Cook, held in reserve. While the armored infantry remained mounted on the vehicles of 1st and 3rd Platoons, the 2nd Tank Platoon went in without direct infantry support.

German infantry and tanks during their drive through the French province of Lorraine toward Germany.

In support of B Team, A Company’s tanks to their right provided covering fire on the road between Singling and Bining, while the tubes of the 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion laid down a smoke screen between the American attackers and the heights north of Singling. The Hellcats tried to do their bit by providing direct fire on the town but were chased away by German artillery fire.

As the different tank detachments reached the southern outskirts of Singling, the 1st Platoon veered to the right while 2nd Platoon swung to the left as the 3rd Platoon, accompanied by Leach’s and the 94th Armored Field Artillery’s forward artillery observer tanks, headed straight for the center of town. The company then advanced in a line 700 yards long, the entire length of Singling. As the southern boundary of Singling was reached, the attached forward artillery observer, Lieutenant Donald Guild, adjusted the friendly artillery fire deeper into the village and then ordered it ceased completely as the Americans entered Singling.

Cowgill’s Advance on the City Center

Racing ahead, Farese’s outfit drove onto a slight rise covered by an orchard, which allowed him to observe the road leading into the west end of Singling. It was an excellent position from which to enter the hamlet, and the Germans had it covered in anticipation of such a move with several Panther tanks, two self-propelled guns, a towed 75mm antitank gun, and a machine-gun emplacement just short of the north side of the orchard. As Farese’s command tank crested the high ground in the orchard it was shot to pieces and its young commander killed. After their lieutenant was killed, the remaining three tanks of 2nd Platoon stayed below the slope within the orchard until they were ordered a little later to go east to join 3rd Platoon near the center of town.

While 2nd Platoon was stopped cold to the west, 1st and 3rd Tank Platoons reached the hedge-lined southern part of Singling. There the accompanying infantry of Lieutenant Daniel Belden’s Company B, 51st Armored Infantry Battalion dismounted from its tanks and prepared to assault the building to the left (west), and right (east) of their debarkation point to secure the village. Lieutenant William P. Cowgill’s 3rd Platoon, 51st Armored Infantry was to go west and head for the town square. Lieutenant Theodore R. Price and his 1st Platoon would maneuver to the east side of town, while Lieutenant Norman C. Padgett’s 2nd Platoon would tackle the three buildings 3rd Platoon had been ordered to bypass.

As Cowgill and his troopers neared the town center they saw an enemy self-propelled gun trundling toward them from the west side. Ducking for cover in the nearby buildings, the lieutenant was able to message back to Captain Leach, who was following 3rd Platoon with his tanks, of the presence of the enemy. The Americans commenced firing volleys of submachine gun and rifle bullets at the gun, causing it to retreat down the street to the west, firing at the Americans as it reversed course.

Anti-Tank Fire in Singling

As Leach and Cowgill exchanged fire with the Germans, Lieutenant Guild, the attached forward observer from the 94th Armored Field Artillery, went searching for an appropriate spot from which to direct artillery rounds into Singling. After capturing a lone German manning a machine-gun nest, Guild climbed the church steeple near the center of town. His hope of using it as a good vantage point was dashed when he was fired upon by the same enemy SP gun with which Leach and Cowgill had been recently dueling. He quickly made his way out of the shattered church.

Leach decided not to follow the German gun with his tanks directly through the confined streets of Singling. Instead, he planned to have Cook’s tankers flank the enemy gun by moving farther west and enter the town from the south. After briefing Cook on his mission, Leach set up his headquarters overlooking the town square.

Cook and three Shermans (no infantry was allotted to them) advanced through an orchard south of the village, then turned north through a line of houses into the main east-west road bisecting Singling, halting in an enclosed walled garden. Soon they were coincidentally joined by Cowgill’s infantrymen, who had been working their way west clearing houses as they went. As the foot soldiers neared Cook’s stationary tanks, they spotted two SP guns not more than 200 yards from the unsuspecting U.S. tank crews.

A short firefight between the German SP guns and the now warned American tankers erupted, followed by a cat and mouse game as both sides jockeyed for favorable firing positions between the buildings. Advised of Cook’s situation, Leach got word to the remnants of Farese’s platoon to move east and attack the Germans from behind. However, as soon as 2nd Platoon tanks nosed their way west they were struck by heavy antitank fire. What was left of 2nd Tank Platoon returned to its refuge in the orchard at the west end of town. Later in the day, after another of their tanks was hit by enemy fire, it was ordered to join the 3rd Tank Platoon in the center of Singling.

Cook traveled to Leach’s command post, where he, Leach, Belden, and Guild discussed the best course of action. After dismissing the options of using an artillery barrage or mortar attack to drive the enemy armor away, Leach decided to send two bazooka teams to attack the Germans. Creeping into an attic overlooking their targets, the armored infantrymen fired away with mixed results. One of the bazookas malfunctioned and never got off a shot; the other fired five rounds and managed one hit, causing the German crew to abandon its vehicle. In response, a Panther tank placed two well-aimed shots into the American position, destroying the house and causing the miraculously unhurt GIs to run back to friendly lines.

The German Counterattack

Meanwhile, back in the town’s center Price’s armored infantry captured about 15 Germans holed up in a pillbox. Moments later the Americans were subjected to a vicious fusillade of German mortar and artillery rounds, which caused no losses to the infantry. After the artillery attack, a number of well-placed rounds from a Panther eliminated one U.S. tank and forced the rest of 2nd and 3rd Tank Platoons to seek shelter southwest of town, leaving Price’s infantrymen to fend for themselves in the buildings they occupied.

While Cook tried to deal with the German armor and Price and 2nd and 3rd Tank Platoons huddled under enemy artillery fire in the town’s center, at the east end of the village 2nd Platoon, 51st Armored Infantry Battalion, under Lieutenant Padgett, faced its own crisis. Ensconced in a well-fortified building on the east edge of town, Padgett saw a German rocket launcher 800 yards away and seven enemy tanks sitting atop a ridge to the northeast. Steeling himself for a hard fight, he sent a courier to find his 2nd Squad, which had been detached earlier to clear some houses that Belden’s main force had elected to bypass. To deal with the expected enemy tank assault, Padgett could call on Goble’s four 1st Platoon Sherman tanks, which had taken station near Padgett’s men when they initially occupied their fortress-like house.

Padgett was correct in his assumption that an enemy attack was imminent. Having pushed the Americans back from the west and center of Singling, the Germans decided to hit them from the east and northeast.

Notified of the concentration of enemy tanks, Lieutenant Goble detailed one of his vehicles, Sergeant Robert Fitzgerald’s Sherman with the new high-velocity 76mm gun, to guard the eastern and northeastern approaches to Singling. While performing this vital duty, the sergeant destroyed a Panther he was able to ambush east of the town. Moving farther in that direction, he spotted another Panther, which retreated. A little later, after firing three armor-piercing rounds at his target, Fitzgerald was able to dispose of a second Panther.

No sooner was his latest victim set ablaze than Fitzgerald engaged a third Panther at a range of 800 yards. Two rounds screamed from the American 76mm cannon, hitting the enemy on its frontal armor and barely making a dent. Fitzgerald wisely backed his tank out of the German line of sight. The sergeant left his mount to confer with Lieutenant Padgett and scout the landscape. His eyes instantly fixed on an enemy SP gun heading east, and the American got back in his tank and set up an ambush. However, the German gun never reappeared. As Fitzgerald waited in vain, other German armor blew apart Lieutenant Goble’s tank.

Not So Silent Opposition

Amid the chaos of battle in Singling, around noon Abrams was notified by Combat Command A’s commander, Brig. Gen. Herbert L. Earnest, to turn over the village to the arriving Combat Command B and get ready to move on Bining and Rohrbach-les-Bitche. The force that would relieve Combat Command B was made up of elements from the 8th Tank and 10th Armored Infantry Battalions under the leadership of Major Albin F. Irzyk. Irzyk was surprised to learn that Task Force Abrams was even in the area, and after meeting Abrams in the southern part of town was told by the latter, even as gunfire continued to be heard, that all opposition had been silenced, the town secured.

The 8th Tank Battalion chief, relying on the assurances of the esteemed Abrams, sent one of his companies escorted by a few armored infantrymen through the southern part of Singling to take over the positions currently held by the 37th tankers. The first tank of Company B, 8th Tank Battalion to enter the town from the southwest was knocked out by two rounds of German antitank fire. Clearly, Singling was not free of Germans as Abrams had declared.

As the afternoon wore on, Abrams was anxious to quit the town. He called Leach’s command post to find out how the handover to Irzyk’s boys was going and was told that the Americans had seen five German tanks moving around the west end of town and five more opposite the town’s center. In addition, a heavy concentration of enemy artillery fire was falling on the village. With German activity still persistent in and around Singling, Irzyk suspended his move to relieve Abrams, something the 51st and 10th Armored Infantry Battalions were unaware of as the former withdrew from Singling and the latter took up defensive positions in the hamlet.

Securing Singling

By nightfall B Team had pulled out of Singling, some 10th Armored Infantry soldiers occupied parts of the village, but no 8th Battalion tanks were in town to support them. Major Irzyk decided to evacuate all his men from the town that night. The following day his command moved up just short of the crest of the Singling ridge south of town but was ordered not to advance since the entire 4th Armored Division was to be taken out of the line and replaced by the U.S. 12th Armored Division. Singling was finally secured by the Americans of 12th Armored Division about December 10, 1944, after a brief 45-minute assault; Bining and Rohrbach-les-Bitche passed under U.S. control that same day.

The fight at Singling on December 6, 1944, cost the Americans six killed (all tank crewmen) and 16 wounded. Five Sherman tanks were knocked out on the 6th in addition to the 14 destroyed or disabled on the 5th. About 60 Germans were taken prisoner, and two confirmed Panther tank kills were recorded. While the inconclusive fighting raged at Singling, the rest of Task Force Abrams, spearheaded by the M5 Stuart light tanks of Company D, 37th Tank Battalion and helped by the German preoccupation with the defense of Singling, managed to penetrate into Bining.

The Three Mistakes Made at Singling

While the action on December 6, 1944, represented 4th Armored Division’s high water mark in its drive toward the German fortified border area known as the West Wall or Siegfried Line, the engagement revealed some glaring deficiencies in the unit’s combat performance. These resulted from the fact that the operation to go for Bining and Rohrbach-les-Bitche was a last-minute affair that should have been deferred until 4th Armored was relieved by the 12th Armored Division. Once decided upon, the attack could only be based upon a hastily improvised plan that did not take Singling into account and thus denied the attackers a reasonable chance of success.

Due to the hurried plan to take Singling, 4th Armored Division did not have time to do a number of basic things that might have assured success. First, there was no time allotted to make needed aerial reconnaissance over the Singling-Bining-Rohrbach-les-Bitche area to determine the lay of the land and learn the enemy’s location and strength. As a result, follow-on air strikes were not ordered to soften up the targets.

Second, no time was allowed for Task Force Abrams to conduct ground scouting toward its objectives before the American advance began on either the 5th or 6th of December. This deprived the attackers of any knowledge of the ground conditions and strength, location, or type of opposition they would encounter at Singling.

Third, a breakdown in interdivision communications prevented not only the needed initial artillery support Lt. Col. Abrams called for, but also jeopardized the speedy and safe relief of the 51st Armored Infantry by the newly arrived 10th Armored Infantry, and subsequently the support and withdrawal from the village of the 10th infantrymen by the 8th Tank Battalion.

Tensions Between Manton Eddy and John Wood

The question remains as to why so many of the routine tactical requirements that the division’s units always employed before and during combat were missing at Singling. The answer may be due to the state of confusion at the top level of divisional command in the first days of December 1944.

Trouble between Manton Eddy and his subordinate, John S. Wood, commander of 4th Armored Division, had been brewing since mid-November 1944, when the former complained that the latter was not driving hard enough during the opening stages of Third Army’s winter campaign. The situation between the two generals worsened on December 2, when in an insubordinate manner Wood defended the performance of his men to his superior, Eddy. This was just the most recent time Wood had shown disrespect for Eddy’s authority. After Eddy again complained to General Patton about Wood’s conduct, the commander of the 4th Armored Division was relieved the next day.

“Tiger Jack” Wood was loved and respected by the officers and men of the 4th Armored, and this emotional attachment with his troops strengthened the performance of the whole unit. He was known as a proficient and dynamic tank commander. As a result, his relief and replacement by Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey stunned the division, angered and discouraged many unit leaders, and for a while threw its command structure into confusion. This confusion at division level eliminated Combat Command A’s control of the battle for Singling, bypassing it and giving direct orders to Abrams. One result of this was that Abrams’s requested artillery support was not pushed by Combat Command A since it felt it could not authorize the support since it appeared division was calling the shots.

The unsteady hand exhibited by division because of the change of commanders also contributed to the lack of support Abrams might have received during the battle from units such as Major Irzyk’s. Irzyk did not know Task Force Abrams was in his vicinity and was never notified by division that help was needed at Singling. The confusion at division headquarters after Wood’s ouster prevented it from properly monitoring the progress of the battle, which might have diminished Abrams’s rather poor management of the operation.

The guiding hand of Wood was sorely needed and missed during the fight at Singling.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments