By Peter Suciu

Anyone who has ever visited Europe—particularly France, Italy, and the Netherlands—knows that the people in those countries love their bicycles. Bicycle racing is one of the most popular sports in Europe, trailing only football (soccer) in overall popularity. And for many Europeans, cycling is how people commute to work, get to the store, and, whenever possible, get away from it all. But cycling also has a long and colorful military history that includes combat service in various armies in Europe and the rest of the world.

As with the automobile, no one person can claim to have definitively invented the bicycle. The first person generally credited with creating a two-wheel device that would be the forerunner of the modern bicycle was German Baron Karl von Drais, who in 1817 devised an in-line contraption that was propelled by the rider’s feet. This horse substitute, called the Laufmaschine, or running machine, was aimed at the well-to-do, but did not catch on with its target audience.

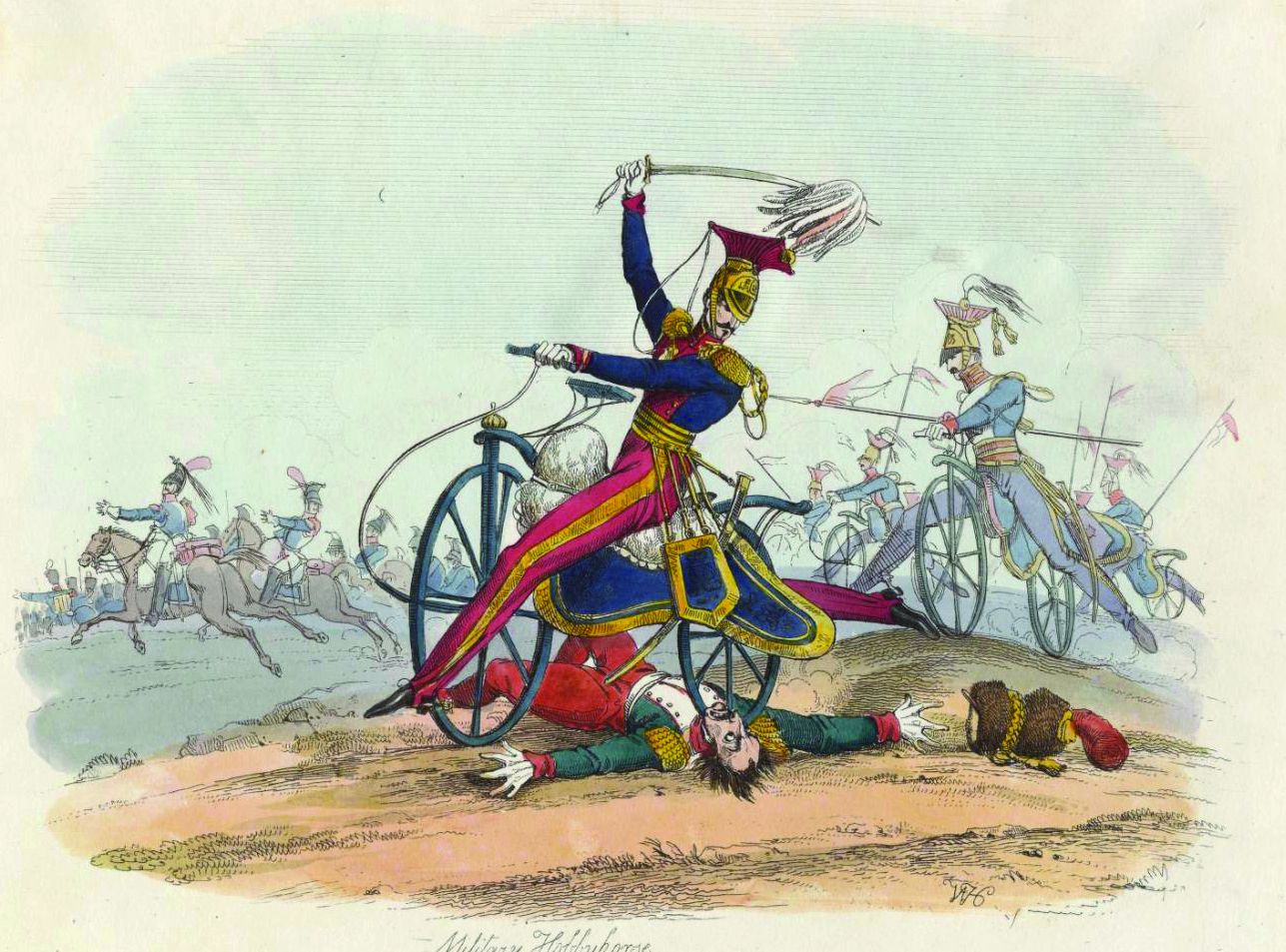

Other inventors and tinkerers attempted to create a human-propelled machine, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that Frenchmen Pierre Michaux and Pierre Lallement introduced a pedal-driven system that would greatly advance bicycle technology. New innovations in pedal-driven systems are now known to collectors as the “ordinary bicycle,” or the “penny-farthing.” These featured a tall front wheel and a lower back wheel, which gave the vehicle its nickname for the comparative size of British coins. The bikes were difficult and even dangerous to ride, as they had a high seat and poor weight distribution. These first bikes were novelties for wealthy men—no proper lady would ever consider riding one—but they did introduce the French to their long-standing love affair with the bicycle, one that continues to this day. While awkward to ride, the bikes were tested by the military for dispatch carriers and scouts.

Ironically, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 destroyed the fledging French bicycle industry, but it was far from the end for bicycle innovation. Instead, development progressed in Great Britain and the United States, where advances included a chain-driven system that allowed for a more stable riding platform. English inventor John Kemp Starley followed up on this development and produced the world’s first successful “safety bicycle,” which was called the Rover and released in 1885. It featured a design that would be recognizable today, with a steerable front wheel, equally sized front and back wheels, and a drive chain connecting to the rear wheel. The safety bike concept caught on during the 1890s, and military thinkers saw its combat potential.

The late 1880s and 1890s saw many nations experiment with bicycles. The Austrians and Germans each looked into the possibilities of using the two-wheeled contraptions, but it was the French Army that formally introduced the bikes into service in July 1887. However, the British beat their continental rivals to the finish line, using cyclists as scouts during field maneuvers in 1885.

Americans soon followed suit, with various National Guard regiments experimenting with bicycles. In 1891, the First Signal Corps of the Connecticut National Guard was the first American force to have a formal military bicycle unit. The bicycle was used by messengers and relay riders, and the U.S. military took on various challenges. One Connecticut National Guard cyclist proved that he could personally deliver a message faster than an entire flag signaler team, while a relay team carried a single dispatch from Chicago to New York City in just four days and 13 hours, much of the time in rainy weather. A follow-up challenge brought a message from Washington, D.C., to Denver in just 6¼ days. Clearly, the bicycle could deliver the mail, but it still had to prove its place in wartime conditions.

While the bicycle proved that it could deliver messages via a dispatch rider, there were also experiments to have the bicycles do other duties. The bicycle was adapted for use by portable topographers and telegraphers. In the former case, a rider used his bike to study the grade of hills and other terrain to help commanders in the field determine if the land was traversable by cannons and wagons, while in the latter use, the bikes were used to lay cable from a command post to the front. Both uses seemed practical at first to designers, but in the field they proved otherwise.

Various nations conducted tests to see if a bicycle could be used as an actual gun platform, and the 1890s saw a series of strange designs, including sidecar-mounted machine guns and side-mounted rifles that could be fired from the handlebars. These prototypes not surprisingly failed to go very far, and few of these early gun-bearing bicycles survive, even in museums.

When the bicycle proved unable to be transformed into a new type of weapon, some nations instead looked to see if they could devise tactics to use the bike in combat. This occasioned the first practical study of tactics for bicycle riders—just in time for the bike to head off to a real war. It was during the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa, which began in 1899, that the bicycle was first used in an actual conflict. Cycles were used by messengers, adapted into portable stretchers, and even used as a part of a specially devised two-man cycle to patrol railroads. In the latter case, about 20 were built for patrol work, but none survive today.

Use of bicycles was not limited to the British, as their Boer opponents also adopted bikes, with Boer commandos using them in place of horses on a limited scale. Neither side attempted any frontal charges with the bikes, but they were used to get troops into the fighting and as an alternative for patrolling in hostile territory. The bike had been tested in battle, and it looked as though it would find a place in future wars.

However, it was still not to be as a frontline weapon. World War I, which had begun as a mobile and fluid conflict, at first seemed to be ideal for bicycles. Both sides used a large number of bikes to help troops get to the front lines quickly. But as the war bogged down into the hellish nightmare of trench warfare, the two-wheel machines were relegated to rear echelon duty. Cycles were used to some degree by sharpshooters in less static areas, as well as by scouts and dispatch riders.

Following the war, the European interest in bikes expanded into leisure and sports. In the United States, too, cycling began to catch on, with venues such as New York City’s Madison Square Garden hosting daylong cycling races. With the advent of the radio, cycling faded as America’s premier sport, giving way to baseball, which was easier for announcers to call. Yet across the ocean cycling remained popular, and bicycles remained machines of war as much as machines of sport and peace.

A generation after the trench warfare of World War I, the renewed outbreak of war in Europe and Asia put bicycles back in the field. The German Army, even during its rapid-moving blitzkrieg campaign, still relied on horse-drawn carriages to transport men and equipment, and bicycles too played a part. There is a misconception that the Germans were fully mechanized and motorized during the war. In fact, Adolf Hitler invaded Russia with more horses than even Napoleon. For this reason, the bicycle was used in great numbers by the Germans for reconnaissance.

Wartime shortages throughout World War II also resulted in many nations utilizing the bicycle to save on fuel. This was especially true in isolated Great Britain during the Blitz, and followed even after the Yanks arrived in great numbers. The United States, which was also on wartime rationing, used bikes in great numbers, but unfortunately for collectors, few of American bikes survived the war.

“Given the rarity of these bikes today I would say it’s safe to assume that compared to other mass-produced military vehicles, bicycles were actually made in fairly small numbers,” says militaria collector Johan Willaert, who specializes in American Army items from World War II, including bicycles. “A lot of them must have been shipped over to the European and Pacific Theaters, but it seems a lot more were kept and used stateside.”

Willaert believes that there are actually more World War II-vintage bikes in European collections than in the United States, because most of these were bought in the States and shipped to Europe by collectors in recent years. “I know of only a handful of real ‘left-behind’ bikes in Europe while it seems they were not that uncommon in postwar surplus sales in the U.S.,” Willaert says. “I think they were used much more at U.S. camps and airfields than in Europe. The U.S. Army was much more mechanized and had no bicycle troops as such.”

Unlike other American gear from World War II, little information survives about the total numbers of bicycles produced. “It is not clear just exactly how many bikes were made for the U.S. Army on official wartime contracts,” says Willaert. “There seem to be no lists left or they haven’t surfaced to this day.”

While bikes were never utilized in great numbers by Americans, and in only a limited frontline role by the British military, a wartime enemy of the Allies used cycles in much larger numbers. “It was probably the Japanese who used the bicycle most during WWII,” says Robert van der Plas, coauthor of Bicycle Technology. “The invasion of Malaysia, with thousands of soldiers rolling into Singapore on bicycles, is one of the best-known instances. They used both folding bikes specifically designed for warfare, later rehashed for civilian use, and requisitioned bicycles from other occupied territories.”

The Japanese proved able to adapt and overcome obstacles with their bicycles. Since rubber was in short supply, Japanese soldiers learned to ride on the rims when the tires went flat and couldn’t be repaired.

After World War II, many of the wartime bikes passed to civilian hands as the world recovered from the horrors of war. This was especially true in Europe, where fuel was still hard to come by and where there had been an existing bike culture. “Bicycles have been a part of European history and culture for many, many years,” says Willaert. “For ages the bicycle has been a means of everyday transport for thousands of people, especially in Belgium and the Netherlands. The bicycle was a cheap and easy means of transport for people who couldn’t afford a car for decades.”

While the bicycle was transformed into a means of civilian transport, it still remained a tool of war. In the Vietnam War, Vietcong and North Vietnam forces utilized bicycles in great numbers. Bikes were also used in other rural conflicts in Central America and Africa and are still used today by American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Ironically, two nations that used bikes in the greatest numbers have never actually used them in anger. These are the neutral nations of Sweden and Switzerland, each of which has rugged terrain and an independent spirit. Sweden was among the forerunners of bicycle technology for military use, and the 27th Gotlandic Infantry Regiment replaced its cavalry complement with bicycle-mounted troops in 1901. By 1942, the nation had six bicycle infantry regiments.

From 1948 to 1952, however, the Scandinavian nation began to decommission its bicycle infantry regiments, and by the 1980s only special bicycle rifle battalions remained. Most of the military bikes were sold off, and these are encountered in limited numbers on the private market. For collectors there are a number of models on the market, and those from the wartime era tend to be more desired by collectors, even though Sweden didn’t take an active part in World War II. Commercial versions based on past military designs are also available today, but these were never technically used as military bikes.

Europe’s other major neutral power, Switzerland, also has a long history of military bicycles. The Swiss followed the Swedes in adopting the bicycle for use by the infantry, with a special bicycle regiment introduced in 1905 and phased out only in 2001. The bikes that the mountainous nation used are known for their high quality and durability.

“Switzerland had a major shift in 1988 or thereabouts, and disbanded the original bicycle corporation,” says Patrick Robb of Cold War Remarketing. The country’s military transformed the bicycle units, in part to introduce a new and more modern bicycle. “This new bike was about $3,500 so it was significant,” adds Robb. “What they did was to introduce a training program where you had to buy the bike, and at the end of the training you were refunded for the cost for the bike.”

This updating resulted in Switzerland selling off nearly all of its military bikes, and Robb’s company is among the largest dealers of the famous Swiss Army bikes. From the late 1990s to 2004, the company was able to obtain several hundred bikes at a time. “We’re not seeing those numbers anymore,” says Robb. “Now the majority of the liquidation of the old bikes has happened, and the deals are no longer available.”

The glut of Swiss and Swedish Army Bikes may have passed, but collectors can still find many bikes on the market today. As with any military collectible, caution needs to be taken. While outright fakes are uncommon, in part because the market for collectors of military bicycles isn’t that great, many bikes are not exactly what they appear to be. “I wouldn’t say these bikes are faked when you consider a fake as being something that is newly made especially to resemble something else or similar to something that was made in the past,” says Willaert. “But it also gets confusing, as many straight-off-the-shelf civilian bikes were put to use by the armed forces in their constant effort to conserve rubber and gas consumption. Some were repainted olive-drab and some even kept in their original color and chrome finish.”

Willaert warns that it is easy for someone to repaint an old bike, even one from the 1950s, and claim that it is of wartime vintage. Likewise, many Swiss and Swedish bikes are often passed off as German, since all things German tend to carry a premium when it comes to World War II collectibles. Folding bicycles, which often are classified as “paratrooper bikes,” are also highly desirable, even if most probably never actually made a jump.

For the collector who wants to get started, Montague Bicycles currently offers a paratooper model, which was developed for the United States military and is currently used around the world by the Marine Corps and Army Special Forces. Following landing, the full-sized aluminum mountain bike can be deployed in less than 30 seconds. Even in the age of Predator drones and high-tech warfare, the bicycle is still rolling on the battlefield.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments