By Sam McGowan

When World War II in Europe came to an end, the Eighth Air Force was the most famous unit in the U.S. Army Air Forces and, until the massive Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids against Japan in the spring of 1945, it was the most powerful.

After more than two years of aerial bombardment of targets throughout Germany and Occupied Europe, the Eighth Air Force had come to symbolize heavy bombing. While the Eighth is known as the heavy bombardment outfit, it did not start out that way. When it was first established on January 2, 1942, the unit that became famous as the Eighth Air Force was actually designated as the Fifth Air Force. However, this number had already been reserved for an Air Corps unit in the Southwest Pacific, so the designation was subsequently changed to the Eighth.

Nor was the Eighth conceived to be solely dedicated to aerial bombardment; its original mission was tactical. It came into existence to serve as an air element to support Operation Gymnast, the planned invasion of Northwest Africa that was scheduled to take place later in the year.

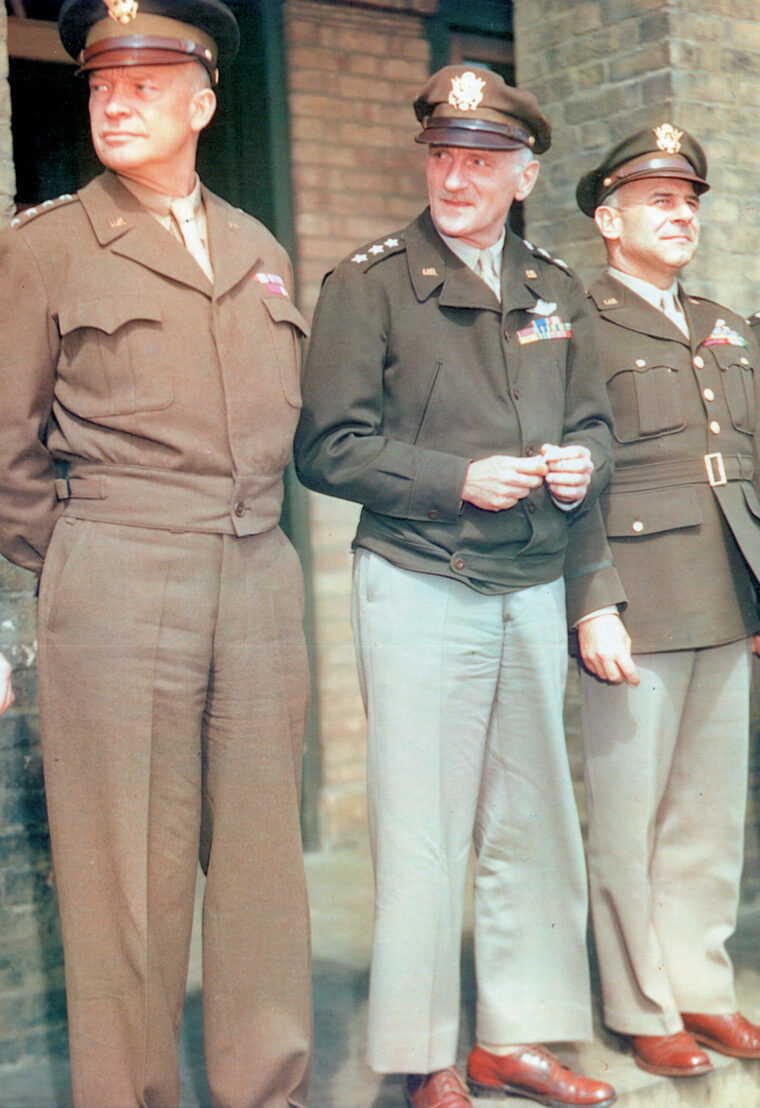

On January 28, 1942, Eighth Air Force Headquarters was activated at Savannah Army Airfield, Ga., under the command of Colonel Asa N. Duncan. Over the next several weeks the Eighth underwent several changes. Gymnast was canceled due to the emergency situation in the Pacific, eliminating the need for the new unit as it had originally been conceived and leaving it without a mission. One Army plan called for the establishment of an Army Air Force in Great Britain. On March 31, Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, commander of the Army Air Force Combat Command, proposed that the taskless Eighth Air Force be made available for duty in England and that he be chosen to command it. General Ira Eaker had already gone to England with an Army Air Forces advance party, and Spaatz decided that it would pave the way for his new command.

With the change in task, the size and makeup of the Eighth changed as well. Previously, Colonel Duncan had requested the assignment to England of three heavy bomber groups, two groups of medium bombers, and three fighter groups. The reorganization for the new mission increased the planned size to 23 heavy, three medium, and five light bomber groups, along with four groups of dive-bombers and 13 fighter groups. Two troop carrier groups would also be added. The dive-bomber groups would never materialize, and the light bombers would become part of a new organization when they finally arrived in England.

In April Duncan, who had been promoted to brigadier general, was made subordinate to Spaatz, and the headquarters was split into two echelons. Administrative functions remained in Savannah while operations moved to Bolling Field on the outskirts of Washington, DC, near Spaatz’s headquarters. General Spaatz took formal command on May 5, and preparations began to move the Eighth to England.

Shortly after Spaatz assumed command, an advance echelon left for England, where it joined Eaker’s organization, which had been redesignated as the Army Air Forces British Isles. Other Eighth headquarters personnel followed over the next few weeks. In mid-April Eaker took over a girls’ school at High Wycombe for his headquarters.

Eaker’s role was to prepare the way for the arrival of the Eighth Air Force staff, so in the interim his organization was redesignated as Detachment Headquarters, Eighth Air Force. Eaker’s staff worked diligently to develop a plan of action for the combat units when they arrived in England, with particular emphasis on bombardment. They borrowed heavily on the experiences of the British and closely followed the lines of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command in developing the organization. When Spaatz arrived in England, Eaker became commander of VIII Bomber Command and Brigadier General Frank O’D. Hunter was placed in command of VIII Fighter Command.

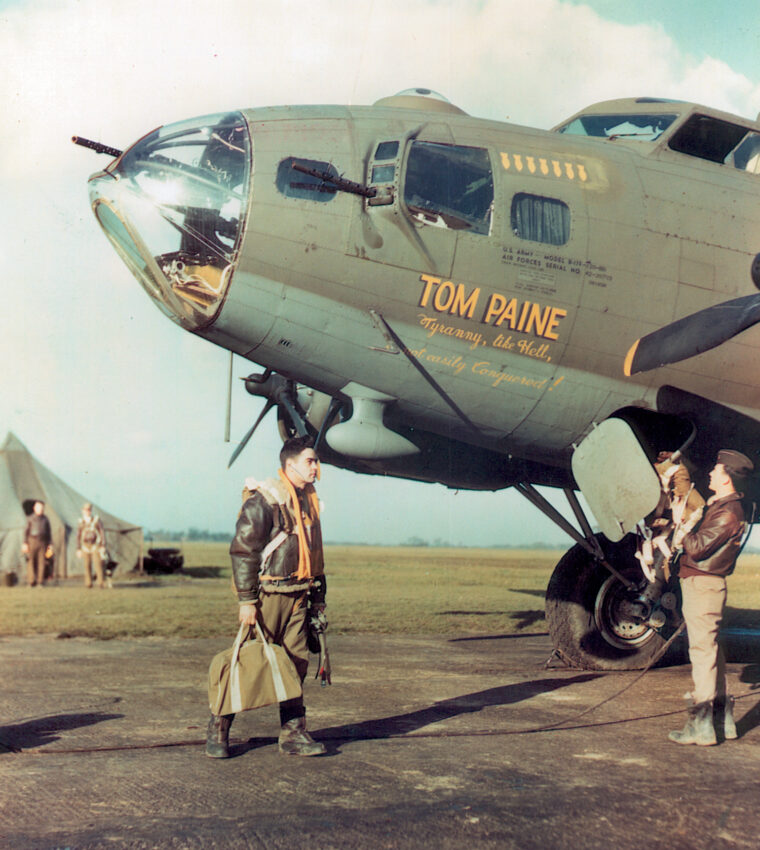

The movement of the combat units to England was delayed by the Battle of Midway when the 97th Bomb Group and some fighter groups were sent to the West Coast. When the battle concluded, the combat units began their move, with the 97th Bombardment Group and the 14th Fighter Group the first to go. The first Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses arrived in England on July 1, followed by Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters. Several fighter groups that had been equipped with Bell P-39 Airacobras left their airplanes behind and were equipped with Supermarine Spitfires when they arrived overseas. The Eagle Squadrons, three Royal Air Force fighter units made up of American volunteers flying Spitfires, transferred into the U.S. Army and joined VIII Fighter Command as the 4th Fighter Group later in the year.

Interestingly, the first Eighth Air Force unit to fly a combat mission wasn’t a B-17 outfit, nor had it been intended as a bombardment group. In May 1942, the 15th Bombardment Squadron deployed to England as an independent squadron to fly Douglas A-20 Bostons as night fighters. When they got there the squadron’s crews learned that the British weren’t using their DB-7 Bostons in that role, so they began training for light attack missions with RAF 226 Squadron.

By the end of June several crews were considered combat-ready, and Spaatz decided to put them into action. The first mission was set for the Fourth of July; six U.S. Army crews were assigned to fly six RAF Bostons on a low-level mission with six RAF crews against German airfields in Holland. The results were less than spectacular. Four crews failed to find the targets, two airplanes were shot down, and a third was badly damaged. An RAF Boston was also lost.

One of the American pilots, Captain Charles C. Kegelman, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for attacking a German flak tower with only one operating engine. The 15th Bomb Squadron soon received its own Bostons and for several weeks was the only Eighth Air Force bomber unit flying combat missions.

Spaatz Wired an Exaggerated Account to Washington That the Bombing “Far Exceeded” any Previous Bombing by British or German Planes in Accuracy.

After a weather cancellation on August 10, the 97th Bomb Group flew its first mission on August 17, 1942. Twelve B-17s attacked a railroad marshaling yard at Rouen, France, while six others made a diversionary sweep along the French coast. General Spaatz watched the bombers take off and General Eaker flew as a passenger in the lead airplane. Escorted by RAF Spitfires, the B-17s set out across the English Channel under generally clear skies. All 12 airplanes dropped their bombs, and about half fell in the general vicinity of the target. One of the aiming points was hit, while the second was missed by about half a mile.

Spaatz wired Washington that the bombing “far exceeded” any previous bombing by British or German planes in accuracy. He claimed that the results “justified” American faith in “daylight precision bombing” and optimistically asserted that the mission proved that “the bombers could get through.” His claims were a bit of an exaggeration—only three German fighters had actually attacked the formation, while several others observed from afar. Damage from antiaircraft fire had been “slight.”

The first fighter attacks came on August 21, when the bombers arrived over the coast of Holland without a fighter escort due to a communications foul-up. Even though a recall message was sent out, German fighters intercepted the bombers. Surprisingly, in spite of attacks by more than 40 Luftwaffe fighters, only one of the B-17s suffered serious damage and the co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Donald Walter, who died of wounds, became the Eighth’s first heavy bomber combat casualty. The gunners claimed scores of German fighters, but the final number was determined to have been two shot down, five probables, and six damaged.

The 97th Bomb Group was alone in the daylight heavy bomber role until September 5, when the formation of 37 B-17s including 12 from the newly arrived 301st BG on Mission Number Nine joined in. Another group, the 92nd, made its first contribution to the bombing campaign the following day, when 14 group airplanes joined 27 from the 97th on a mission to Meaulte. Thirteen 301st BG Flying Fortresses attacked the airfield at St. Omer while an even dozen 15th Bomb Squadron Bostons attacked Abbeville. Two B-17s were shot down, the first Eighth Air Force heavy bombers lost in combat.

On October 2, 37 B-17s went back to Meaulte, this time encountering large numbers of German fighters, but all of the bombers made it home. The B-17 gunners put in so many claims that they had to be interrogated twice. The final results were listed as four destroyed, five probables, and one damaged. More than 400 escorting Allied fighters failed to keep enemy fighters away from the bombers.

On October 9, the Eighth Air Force flew its first truly large-scale mission to Lille. The mission consisted of 108 heavy bombers, including two dozen Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the 93rd Bombardment Group on their inaugural mission. The B-17-equipped 306th Bombardment Group was also on its first mission. German opposition was fierce, as it was their first real effort against the bombers. The Luftwaffe ignored the British and American fighters and went straight for the bombers, shooting down three B-17s and one B-24. Four B-17s suffered heavy damage, while another 32 B-17s and 10 B-24s received slight damage.

Initial claims by the gunners were 56 destroyed, 26 probables, and 20 damaged, an impossible score since it would have accounted for 15 percent of the estimated Luftwaffe fighter strength in Western Europe. This number was subject to constant revision over the next several months and finally went in the books as 21 destroyed, 21 probables, and 15 damaged. These numbers were still too high since British intelligence believed that no more than 60 German fighters could have possibly intercepted the formation.

In October the Eighth Air Force lost much of its strength to the Mediterranean Theater. Two B-17 groups and nearly all of the fighters, as well as the two troop carrier groups and the Bostons of the 15th Bombardment Squadron, left to support the invasion of North Africa. The Eighth also lost its commander. When General Spaatz moved to Africa, Eaker took his place. In addition, three squadrons of B-24s from the 93rd also went to Africa for temporary duty. Two new B-17 groups and one of B-24s soon became operational to take up the slack left by the transfers.

The 329th Bomb Squadron from the 93rd BG remained in England to experiment with electronically guided bad weather harassment missions that the crews referred to as “moling.” Unfortunately, the first mission into German airspace was canceled when the B-24s broke out of the clouds into clear weather over the Ruhr! The crews had been instructed to attack only through the clouds to prevent the sensitive equipment from falling into German hands. The fact that American heavy bombers had penetrated German air space for the first time was kept secret.

During the fall and winter of 1942, the main effort of the Eighth was aimed at German submarine pens in France and the Occupied countries. On January 27, 1943, the first large-scale mission into Germany saw a mixed force of 91 heavy bombers, including a small formation of B-24s, go against Wilhelmshaven. The mission met with limited success due to clouds over the target, but the weather also hindered fighter opposition. Two B-24s and a B-17 were lost to fighters, but the bomber gunners claimed 22 enemy aircraft (actual German losses were seven).

Although the Eighth Air Force included a fighter command, operations in North Africa severely depleted U.S. fighter strength in England. For several weeks, the only American fighters still in England were P-38s being held in reserve to reinforce North Africa, and the Spitfires of the new 4th Fighter Group. In January 1943, the 56th Fighter Group arrived in England with Republic P-47 Thunderbolts.

Bomber losses had so far been low, causing the Eighth Air Force leadership to erroneously conclude that the heavy firepower on the bombers was sufficient to defend against fighter attack. When General Henry “Hap” Arnold ordered the transfer of the 78th Fighter Group’s P-38s to North Africa to replace losses, the group was left without airplanes. Both the 78th and the 4th Fighter Group were equipped with P-47s, but it was well into the spring of 1943 before VIII Fighter Command became active in the air war in Europe.

While the 93rd Bomb Group was in Africa, the 44th Bomb Group was left as the only Liberator outfit with the Eighth—except for the 329th Bomb Squadron—for several weeks. When it began combat operations, the 44th endured a number of unfortunate incidents that soon gained the group a reputation as a “hard luck” outfit. The group’s losses came in ones and twos and were as often due to accident as to combat. The heaviest losses occurred on a mission when the leading B-17s got lost and left the B-24s low on fuel (they had only enough fuel on board to complete the mission).

Several airplanes had to crash-land in English pastures. The incident led to the replacement of the group commander by Colonel Leon Johnson, but the losses continued. The 44th’s high losses led some people to begin complaining that the B-24 was inferior to the B-17, asserting that perhaps the B-24s should be withdrawn from the theater.

The Mission was a Failure in Spite of the Low-Level Attack, Which Should have Resulted in Accurate Bombing, as not a Single Bomb Hit the Target.

By mid-March the 93rd had returned from Africa, and on the 18th the two Liberator groups flew their first mission together. Because of their faster speed, the B-24s maintained their own formation within the larger bomber stream. With only two groups of Liberators, and with more and more B-17 groups arriving in England every month, General Eaker began assigning the B-24s to tasks other than daylight bombing. Both groups were understrength, and at one point the 44th had more airplanes than crews.

In late April Eaker selected the 93rd to train for night bombing, using the technology with which the 329th Bomb Squadron was experienced, but the experiment was short-lived. Within a couple of weeks, both the 93rd and 44th were pulled off combat operations altogether to train for a classified mission: a low-level attack on the oil fields at Ploesti, Romania. The 389th Bombardment Group joined them when it arrived in England, and all three groups set out for North Africa for a stint of temporary duty with the Ninth Air Force.

In May 1943, just as the VIII Bomber Command Liberators were taken off combat operations, the medium bombers of the 322nd Bombardment Group made their combat debut—with disastrous results. The 322nd was equipped with the twin-engine Martin B-26 Marauder, an airplane surrounded by controversy due to a high accident rate during ferry flights and in training. On May 14, the 322nd launched its first mission, a low-level raid against a power plant at Ijumuiden on the Dutch coast. The mission was a failure in spite of the low-level attack, which should have resulted in accurate bombing, as not a single bomb hit the target. Several airplanes were hit by flak, and one crew was forced to bail out.

Since the target was left undamaged, a second mission was scheduled for May 17. Half of the force of 11 B-26s was to hit the power plant again, while the other half struck another generating plant at Haarlem. Disaster was the order of the day—only one airplane returned from the raid, and its pilot had aborted before reaching the Dutch coast. The attacking formation got lost and blundered into the most heavily defended airspace in Holland.

Several airplanes were shot down, and two were lost in a midair collision. Every airplane engaged was lost, along with 62 airmen. As a consequence, the B-26s were taken off combat operations until new tactics could be developed. Under the new tactics, the medium bombers were restricted to attacks at medium altitudes from 12, 000 to 15,000 feet where they were out of range of the automatic antiaircraft weapons that were so deadly to low-altitude attackers. They were always escorted, usually by RAF Spitfires, and were very rarely intercepted.

General Eaker had hoped that the B-26s would serve as a diversion to draw German fighters away from the heavy bombers, but the concept was never fulfilled as the German fighters left the mediums alone and went after the heavies. The medium bombers left the Eighth and transferred to the Ninth Air Force for tactical operations when it arrived in England in the fall of 1943.

The summer and fall of 1943 is the period sometimes called “The Fall of Fortresses.” With the Liberators off in Africa, the B-17s were left alone in the skies over Germany and Western Europe. As heavy bomber strength increased, VIII Bomber Command began sending the B-17s on deeper and deeper penetration raids into Germany. With the longer missions came increased exposure to German fighters and antiaircraft fire, and aircraft losses began to mount. The April 17 mission to Bremen was an indicator of things to come: out of 115 B-17s from the 1st Bombardment Wing, 16 were shot down and 46 damaged.

During the early bombing campaign, the Luftwaffe had held its fighters back, leading some air officers to underestimate the true strength and effectiveness of the German fighter force. As Allied bombers began appearing in daylight over Germany in greater numbers, Luftwaffe fighter strength in Western Europe began increasing until it had almost doubled by mid-1943. As bomber losses mounted, the AAF leadership recognized the need for long-range escort fighters. In mid-1943 the only fighter with true long-range capabilities was the Lockheed P-38, but all of those had been sent to North Africa. They were replaced by Republic P-47s equipped with external fuel tanks, but even with the tanks the Thunderbolts were only able to provide escort for 175 miles into enemy airspace. While the P-38s had the range to go deep into Germany, there were none in England until late summer. When they did arrive, the twin-engine fighters were plagued with mechanical problems that temporarily limited their effectiveness.

After a two-week rest in early August, VIII Bomber Command scheduled its most ambitious mission yet: an attack on the aircraft factories at Regensburg, Germany, and Wiener-Neustadt, Austria. The original plan called for the B-17s to hit the targets, then go on to Africa, but since only a few airplanes had been equipped with long-range fuel tanks, a new plan was developed.

The three Eighth Air Force B-24 groups were still in Africa, recuperating from the effects of the maximum-effort, low-level attack on the Ploesti oil fields that had taken place on August 1. They would join the two Ninth Air Force Liberator groups in a raid on Wiener-Neustadt, while the B-17s struck Regensburg in a two-pronged attack that would split the German fighter defenses. The date was set for August 7, but bad weather over Europe kept the B-17s from making the trip and their mission was postponed.

On the 13th, the Liberators went against Wiener-Neustadt, one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe, without the benefit of the B-17s to split the German fighter defenses. Fortunately, the Germans were caught by surprise due to the long distance involved and losses were much lighter than expected.

Finally, on August 17, seven B-17 groups from the 4th Bombardment Wing took off from England on the first “shuttle bombing” mission of the war. After striking Regensberg, they were to continue to North Africa to refuel and rest their crews, then come back to England on another mission.

The 1st Bombardment Wing’s B-17s were assigned to attack the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt. Unfortunately, things did not work out as planned. The 1st Wing was delayed for several hours due to bad weather, then the P-47s that were supposed to escort the trailing sections of the Regensburg force failed to make the rendezvous, leaving the rearmost B-17s unescorted. When the escorts reached their fuel limit and turned back, Luftwaffe fighters came in for the kill and the crews learned that their Flying Fortresses were ambitiously named. The Fortresses were under constant attack for an hour and a half and 17 were shot down with scores damaged.

By the time they reached Africa, 24 B-17s were MIA, including several that ditched in the Mediterranean. The Schweinfurt force also met with vicious attacks and suffered even heavier losses. They fell under attack as soon as they came over land above the port city of Antwerp, Belgium. No fewer than 36 B-17s were shot down. All told, 60 Flying Fortresses and their crews were lost on August 17, and the heavy losses were not going to stop. The B-17 gunners were credited with 288 German fighters, but true German losses were only 25.

By early September the Eighth’s three B-24 groups were back in England. A new group also arrived, bringing B-24 strength to four groups while B-17 strength had increased to 16 combat groups. On September 6, VIII Bomber Command mounted its first large-scale raid since the disastrous Regensburg-Schweinfurt mission as 407 heavy bombers were sent out. The B-24s flew a diversionary mission near the North Sea while the B-17s went to Stuttgart. Contrary to the experience of recent missions, the heavy bombers did not encounter a single enemy airplane!

September also saw the inauguration of a new method of bombing that would allow missions on cloudy days. For several months the Eighth experimented with various methods of “blind bombing,” at first using the British “Gee” navigational system. In early 1943 Bomber Command began experimenting with H2S, a British-developed method using radar for terrain mapping that allowed the operators to identify targets by their topographical features.

The B-17s Caught Hell. As Soon as the Escorts Turned Back, Wave After Wave of German Fighters Began Striking with a Fury.

The 482nd Bombardment Group was chosen to become a “pathfinder” group using B-17s equipped with radar-bombing equipment, an American-built version of the British system designated as H2X. Other pathfinder groups would follow. On September 27 pathfinder B-17s led a force of 305 Flying Fortresses against Emden, while the nonradar B-24s went to Brussels on a diversion. Only one of the combat wings managed to bomb on the Pathfinders’ marker, but the mission broke new ground. Other missions introduced the use of “chaff,” small strips of aluminum foil the crews threw out the waist windows to interfere with the German radar, and electronics countermeasures (jamming) equipment known as “Carpet.”

On October 14, which would come to be known as “Black Thursday,” a large force of B-17s ran into intense enemy opposition on a second mission against Schweinfurt. Weather conditions over England were abominable, but the B-17s assembled using their newly installed navigational equipment. Without electronic guidance, the B-24s encountered great difficulty in the bad weather and only 29 Liberators were able to form up. As this number was too small to go against such a heavily defended target, they went on a diversionary mission.

The B-17s caught hell. As soon as the escorts turned back, wave after wave of German fighters began striking with a fury. Some twin-engine fighters fired rockets, while the Messerschmitt Me-109s and Focke Wulf FW-190s came in close to use their guns and cannon. Losses among the B-17s were even greater than on the previous Schweinfurt mission. A total of 60 B-17s were lost, while 17 required major repairs. One hundred and twenty-one B-17s suffered slight to major damage.

The second Schweinfurt mission clearly demonstrated that the Allies did not have air superiority over Europe and that a continuation of unescorted missions deep into Germany would prove extremely costly in both men and equipment. The apparent answer was to increase the range of the fighters. With two 75-gallon wing tanks, the few P-38s in the theater could operate up to 520 miles into enemy territory; this range could be increased to 585 miles with larger tanks. However, the P-47s were still limited to a maximum of 370 miles. It was not until December that there were enough P-38s available to be effective.

The first North American P-51B Mustang fighters did not become operational until December, and it would not be until March 1944 that the Mustangs had the range to accompany the bombers all the way to their targets. Consequently, the Eighth Air Force made no more raids into Germany in clear weather for the remainder of 1943.

The final months of 1943 brought about some major changes within the Army Air Forces in the European Theater. Since the Ninth Air Force was no longer needed in North Africa, its headquarters transferred to England to form a tactical air force to support the upcoming cross-Channel invasion. Its two B-24 groups joined with three B-17 groups from the Twelfth Air Force to serve as the nucleus for a second force of heavy bombers that would strike at targets in Germany from bases in Italy.

The new unit was organized as the Fifteenth Air Force, with Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle in command. Several heavy bomber groups that had been consigned to the Eighth Air Force were diverted to the new Fifteenth Air Force. A new command organization was planned to control strategic bombing activities in Europe. The headquarters of the Eighth Air Force moved up to become the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSAFE) under General Carl Spaatz, who had returned to England. The former VIII Bomber Command was elevated to Air Force level and became the Eighth Air Force.

The reorganization also led to the transfer of Jimmy Doolittle to England in a purely political move. Some of the high-ranking British officers had taken a liking to the flamboyant and publicity-conscious former air racer when they worked with him in North Africa. They asked General Arnold to bring him to England, which he did over Ira Eaker’s objection.

Doolittle was given command of the new Eighth Air Force while Eaker was moved to Italy to take charge of the new command organization for American air units in the Mediterranean. Doolittle took command on January 6, 1944, the same day that the new USSAFE activated.

Although Doolittle was a national hero, he was far from loved by the bomber crews in the Eighth Air Force. Many saw his famous raid on Tokyo as little more than a propaganda stunt that prolonged the war with Japan, but what really upset them was that, unlike Eaker, he seemed to have little concern for the safety of his crews. One of his first actions was to increase the number of required missions during a combat tour from 25 to 30 at a time when the bomber crews were taking their heaviest losses.

By mid-1944 Doolittle had raised the tour to 35 missions. Doolittle made another controversial decision that did not endear him to the bomber crews when he ordered a change in fighter tactics. Just as enough long-range fighters were becoming available for escort, Doolittle ordered the fighters to range far ahead of the bombers, attacking fighter strips and intercepting German fighters before they had formed up. Although the new tactics eventually contributed to a depletion of the Luftwaffe, at the time it was implemented it left the bombers unprotected. This led to heavy losses among groups that were without fighter cover. Many bomber crews felt that Doolittle was sacrificing them.

At the end of 1943, the Eighth Air Force heavy bomber force stood at 25 groups, reflecting the assignment of several new B-24 groups. A few B-17 groups were still in training in the United States, but most new groups were equipping with the more capable Liberator. All of the B-17s in the Pacific had been replaced by B-24s. The Eighth Air Force would remain a predominantly B-17 outfit due to the groups that were already in theater, but the new Fifteenth Air Force would be dominated by B-24s. For reasons that have never been fully explained, Doolittle preferred the B-17 and attempted to replace all of the Liberators in his command, but the cessation of B-17 production and the impending end of the war in Europe prevented a complete conversion.

With the return of the Allied high command to England, the focus was on the planned cross-Channel invasion of France that was scheduled to take place in the late spring of 1944. Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted upon control of the heavy bombers, a move to which Spaatz objected. Eisenhower’s orders to Spaatz were to obtain complete air superiority over France. Missions in the latter weeks of 1943 and January and early February 1944 were aimed primarily at naval and shipbuilding facilities on the North Sea, usually using the new Pathfinders to mark targets; however, planning for the invasion also led to attacks on the German aircraft industry. In November plans were laid for an all-out bomber offensive against factories building German fighters, but it was not until February 19 that the weather cleared enough to allow the offensive to commence.

The mission of February 20 was the largest of the war to date, with more than a thousand B-17s and B-24s dispatched, along with 17 fighter groups for escort duty. The escorts included two groups of Ninth Air Force P-51s and two groups of P-38s—the only fighters capable of going all the way to the target—but the majority of the fighters were P-47s. Only 21 heavy bombers were lost out of the thousand-plane force.

Only a month before, no less than 60 bombers had been reported as MIA on a single mission, of which 34 were out of a 174-plane force that went to Oscherlaben. The last week of February came to be known as “Big Week” as Eighth and Fifteenth Air Force bombers attacked targets all over Germany. Over the six-day period, 137 Eighth Air Force heavy bombers were lost, along with 89 from the Fifteenth. The daylight offensive was coordinated with British Royal Air Force night raids against the same targets.

Eighth Air Force Lost More than 47,000 Men, of Which 26,000 were Killed in Action, and some 4,000 Heavy Bombers were Reported Missing.

In the spring of 1944, the USSAFE turned its attention to the Axis oil industry and transportation lines. The goal of both campaigns was to reduce the effectiveness of the German Army and Air Forces by depriving them of the petroleum products necessary to operate their mechanized equipment and to reinforce their troops in Western Europe when the invasion began. Oil refineries and railroad marshaling yards were the primary targets.

Other missions were flown against the new V-weapon sites from which missiles were being launched against England. Casualty rates remained high. April 1944 was the costliest month of the war for the Eighth Air Force as 576 aircraft were lost or written off due to enemy action. Of these, 361 were heavy bombers. As the date of the invasion drew near, the Eighth’s heavy bombers joined Ninth Air Force medium and light bombers in attacks on targets along the French coast. On D-day, VIII Bomber Command flew missions against German defenses along the invasion beaches.

The original purpose of the Eighth Air Force was to prepare the way for an Allied invasion of Western Europe through a strategic air campaign against German industry. Once the troops were ashore, the Eighth no longer had a defined mission, but with such a huge aerial armada available, one had to be found for it. The new mission was oriented toward maintaining pressure on the German homeland with daily air attacks on the industrial centers, rear area depots, and transportation arteries. The campaign against German oil production continued. The heavy bombers were also sometimes given tactical missions in support of ground forces.

Even though Allied troops were ashore in France, Eighth Air Force bomber crews and fighter pilots continued to take casualties, often from antiaircraft and ground fire. As German fighter strength weakened, antiaircraft defenses became even deadlier. In July 1944 alone, the Eighth lost 324 heavy bombers; August was close behind as 318 B-17s and B-24s were written off. Losses among Fifteenth Air Force crews were proportionally even higher and would rise, even as Eighth Air Force losses declined, due to the most heavily defended targets in Germany and Austria lying within its area of operations.

Several changes took place within the Eighth Air Force in the summer of 1944. Due to their longer experience with B-17s, the leadership of the Eighth Air Force preferred the Flying Fortress over the Liberator, and five bomber groups of the Third Air Division converted to the older type of bomber.

During the late summer of 1944, hundreds of Eighth Air Force Liberators were temporarily assigned to transport duties, moving cargo and gasoline from England to forward airfields that had recently been captured. One of the most hazardous Eighth Air Force missions of the war was airdropping cargo from B-24s to the American, British, and Polish paratroopers who jumped into Holland. At the end of the war, B-17s dropped food to civilians in areas that had not been liberated by the advancing ground forces.

With the Allied victory in the Battle of the Bulge, it was obvious that Germany was breathing its last gasp as the Russians moved into Germany from the east and the Americans and British from the west. There were still casualties, particularly after the Luftwaffe introduced its new high-performance jet fighters into the war. By April the war was clearly won, and plans were made for the Eighth to transfer to the Pacific and fly B-29s. The Eighth Air Force headquarters did, in fact, transfer to Okinawa, but the war in the Pacific came to an end before any of the combat units became operational.

During two years and 10 months of combat operations, the Eighth Air Force achieved several distinctions. It was in combat longer than any other U.S. Army unit in the European Theater. The Eighth also sustained the heaviest losses of any U.S. military organization, including the entire U.S. Marine Corps. Eighth Air Force lost more than 47,000 men, of which 26,000 were killed in action, and some 4,000 heavy bombers were reported missing.

Sam McGowan is an expert on aviation in World War II. He is the author of The Cave, a novel of the Vietnam War, and resides in Missouri City, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments