By Tom W. Murrey, Jr.

World War II involved some of the most complex alliance systems in the history of warfare. During the course of the conflict, former antagonists became allies and former allies became foes. Of all the alliances struck during the war, the German-Romanian alliance is the one least studied despite the enormous significance of the relationship.

Romania was Nazi Germany’s largest ally on the Eastern Front, providing over 300,000 troops in the conflict against the Soviet Union. Despite the Romanian contribution, the German military took its ally for granted. Consequently, the German Army made serious mistakes and miscalculations that led to the catastrophe at Stalingrad, a debacle from which Nazi Germany never recovered.

Romania’s Folding Borders

Prior to its entry as a belligerent into World War II, Romania suffered an extremely complex and unenviable geopolitical situation. Romania fought on the side of the Allies in World War I and after the war received territorial concessions from the newly formed Soviet Union and Hungary. During the interwar years, Romania continued a close relationship with its former allies, Great Britain and France. When Germany occupied Bohemia and Moravia in early 1939, Romania received an Anglo-French security guarantee.

By the summer of 1940, Romania found itself surrounded by hostile neighbors with territorial ambitions. Its neighbor to the north, Hungary, laid claim to the northern half of the Romanian province of Transylvania. To the east, the Soviet Union coveted Romania’s eastern provinces of Bessarabia and Bucovina. To make matters worse for Romania, in May and June 1940 Germany inflicted a crushing defeat on Britain and France. Situated between the military powers of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and with its closest friends defeated, Romania lay ripe for ravaging.

The Soviet Union moved first. On June 26, 1940, the Soviets issued an ultimatum to Romania, demanding that the Romanians hand over the entire province of Bessarabia and the northern portion of Bucovina. To make matters more difficult, they gave the Romanian government only four days to evacuate the two territories. On June 28, Romania responded that it would acquiesce to the Soviet demands but that it would need more time to vacate Bessarabia and Bucovina. The Soviets reacted by immediately invading the two provinces, and the Romanians avoided a military conflict by quickly withdrawing from the two regions.

The Hungarians victimized Romania next. Since the end of World War I, Hungary had sought the northern region of Romania known as Transylvania. On July 15, 1940, the German and Italian governments ordered Romania and Hungary to negotiate a settlement. The conference took place in Vienna, but negotiations and military threats failed to pry the region from Romanian control. On August 30, 1940, the Germans and Italians unilaterally awarded northern Transylvania to Hungary. The Romanians were given two weeks to evacuate. Known as the Dictate of Vienna, this land grab further increased the bitter enmity between Romania and Hungary.

The final territorial indignity came at the hands of Romania’s neighbor to the south, Bulgaria. Once again, the Germans forced Romania to cede territory, giving the Bulgarians southern Dobruja on September 7, 1940. In a period of less than three months, Romania lost over 100,000 square kilometers of territory, home to 6.7 million Romanian citizens. The immediate result was the collapse of the Romanian government led by King Carol II, who had proclaimed himself dictator in January 1938.

A Pragmatic Alliance With the Axis

In one of his last acts as regent, Carol appointed Marshal Ion Antonescu of the Romanian Army as prime minister. Antonescu immediately forced Carol to abdicate and then assumed the king’s authoritarian powers. Although Antonescu had leaned toward the British and French, in September 1940 France was a conquered nation and Britain could not offer aid to Romania. In an act based more on pragmatism than political belief, Antonescu requested that Germany send a military mission, and on October 12, 1940, the first German troops began arriving in Romania.

As Germany prepared to invade Russia in 1941, Romania faced a momentous decision. Antonescu traveled to Munich where on June 11 Hitler informed him of his plans to invade the Soviet Union. Antonescu pledged Romania’s support in liberating Bessarabia and Bucovina but made no promises as to further operations. At this point, the liberation of Romanian territory was the first and only war aim of the Romanians.

As the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies stood ready on the Prut River, now the new boundary between Romania and the Soviet Union, Marshal Antonescu issued a proclamation to his men: “I am ordering you: Cross the River Prut. Crush the enemy in the east and north. Release your brothers overrun and enslaved by the red yoke of Bolshevism. Restore to Romania’s body the traditional land of the Bassarab dynasty and the forests in Bucovina, your own grain fields and pastures. Soldiers, today you are taking the road of Stephen the Great’s victory in order to conquer by your sacrifices what your ancestors possessed by their struggle. Forward! Be proud that centuries have left us here as guards to justice and as a wall of defense of Christendom.”

With these words the Romanians joined the German Eleventh Army in the invasion of Bessarabia and Bucovina. Despite the presence of over 400,000 Soviet troops, 700 tanks, and some difficult fighting, the two regions were liberated within a month. By mid-August, the Romanian troops arrived on the western bank of the Dnestr River, the former border between Romania and the Soviet Union.

Following the Germans into Russia

The arrival at the former border forced another decision upon Marshal Antonescu. His choices were to advance into Russia alongside the German Army or declare Romania’s war goals complete with the liberation of Bessarabia and northern Bucovina and advance no further. Hitler sent Antonescu a formal request asking the Romanians to continue their advance alongside the German Army. Hitler enticed Antonescu with an offer of the Russian region of Transnistria, which Antonescu refused.

Ultimately, however, Antonescu decided to send his forces across the Dnestr River and into the Soviet Union. He reasoned that if the Germans failed to destroy the Soviet Army, the Soviets would return and reoccupy Romanian territory. Further, Antonescu feared that if Romania did not continue as Hitler’s ally it would be unable to argue for a reversal of the Dictate of Vienna or, worse, that Hitler would award the Hungarians the remainder of Transylvania as punishment. Since the Hungarian Second Army was marching farther into Russia alongside the Germans, Antonescu’s concerns over Transylvania were well founded. Believing he had little choice, Antonescu ordered his armies to cross the Dnestr.

The Romanians spent the remainder of 1941 campaigning in southern Russia and conducting siege operations at Odessa. In the spring and summer of 1942, the Romanian armies engaged in heavy fighting in the Crimea while to the north the German Army attempted to capture Stalingrad. As Hitler funneled more and more German units into Stalingrad, a need arose to protect the German flanks. The task fell to the German allies, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians.

Brushed Aside at Stalingrad

By October 1942, the Romanian Third Army moved from the Crimea to the north of Stalingrad to protect the German left flank while the Romanian Fourth Army held the southern flank. The Italian Eighth Army held the line to the north of the Romanian Third Army. On the Italian left the Hungarian Army was dug in. Because of the long-standing antagonism over Transylvania, the Germans used the Italians as a buffer between the Hungarians and the Romanians to keep them from fighting each other.

The Romanian Third Army consisted of 10 divisions totaling 171,256 men. It held a line anchored on the southern bank of the Don River with the exception of bridgeheads the Soviets had established at Kletskaya and Serafimovich. Each division was assigned to defend a line approximately 20 kilometers long, about twice the recommended distance. The Third Army contained the only Romanian divisions trained by the Germans and consequently was a significantly better fighting force than the Fourth Army, which defended the open steppes south of Stalingrad.

By mid-November 1942, the Fourth Army could boast only 75,380 troops assigned to hold a line over 200 kilometers long. Poorly trained and even more poorly equipped, the men of the Fourth Army lived in holes in the ground covered by canvas as the temperatures dropped to minus 20 degrees Celsius. These living conditions combined with inadequate clothing and supplies of ammunition led to very low morale. Reserves for both the Third and Fourth Armies were limited.

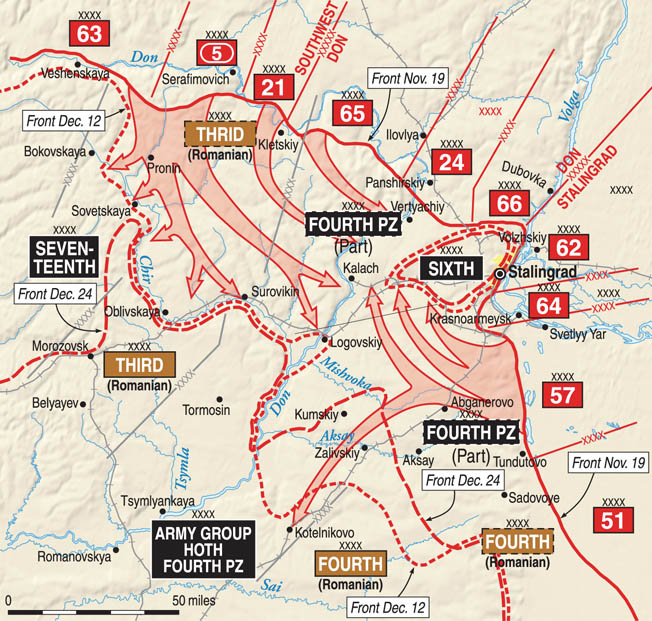

In October and November 1942, Soviet General Georgi Zhukov began assembling more than a million troops for the Soviet counteroffensive code-named Operation Uranus. Zhukov’s plan called for an attack on the German flanks held by the Romanians. The offensive was to slice through the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies and break through to the rear and encircle the German Sixth Army inside Stalingrad. The pincer movement was to meet at the strategic bridge at Kalach, thereby cutting off the Axis line of retreat.

On November 19, the Soviet offensive began with attacks all across the Third Army’s front. After initially tough resistance from the Romanians, the Soviet armor broke through and began the trek to Kalach. On the next day, the Soviets attacked the Romanian Fourth Army, quickly sweeping it aside. On November 23, the Soviet forces met at Kalach, sealing the fate of a quarter million Axis troops. While the Germans blamed the Romanians for this disaster, the real blame belonged to the Germans. The Germans had taken their ally for granted, ignoring Romanian goals and limitations as well as Romanian warnings and pleas for help.

Romania’s Limited War Aims

The first and most glaring strategic mistake the Germans made was their failure to recognize the limited war aims of the Romanians. Romania was not a natural ally of Germany and had in fact fought the Germans in World War I. During the 1920s and 1930s, Romania maintained a close relationship with France and Great Britain. The relationship went beyond just military and political influence. In 1938, foreign investment accounted for roughly 25 to 30 percent of the Romanian economy, and British and French investment accounted for about 70 percent of that total. British and French interests also controlled five of Romania’s major banks. The defeat of Great Britain and France combined with territorial seizures by the Soviet Union forced the reluctant Romanians into the Nazi fold. But the Romanians did not share Nazi Germany’s dreams of conquest.

Antonescu’s decision to cross the Dnestr River and continue the war into the Soviet Union was not popular with the Romanian people. The president of the Romanian National Agrarian Party, Iliu Maniu, expressed this sentiment when he said, “We do not have one Romanian soldier to sacrifice for foreign purposes. We have to spare our army for our Romanian goals.”

Most Romanians thought that their army should follow the example of Finland and fight only to recover territory seized earlier by the Soviets. One captured Romanian officer told his Soviet interrogators that his troops despised Antonescu for “having sold their motherland to Germany.” Between a political rock and a military hard place and with little support on the home front, Antonescu reluctantly continued the war alongside his German allies and pushed farther into Russia.

Instead of being sensitive to Marshal Antonescu’s precarious position, the Nazis engaged in intrigue. Antonescu was considered one of the most loyal of the minor Axis leaders, but this meant little to the Nazis. Heinreich Himmler’s SS openly supported Romania’s indigenous fascist movement, the Iron Guard. The SS even supplied the Iron Guard with submachine guns and in January 1941 tacitly supported the Iron Guard’s coup against Antonescu.

After Antonescu suppressed the coup, the Germans allowed the Iron Guard’s leader, Horia Sima, and 300 followers to take refuge in Germany. Himmler kept Sima and this core of the Iron Guard in Germany as an implied threat to Antonescu’s power for the remainder of the war.

Severe Decisiencies of the Romanian Military

The Germans made another strategic mistake when they failed to properly assess the capabilities of the Romanian military and the individual Romanian soldier. Because of its geopolitical situation and the influence of the French, Romania developed a defensive philosophy for its military. The Romanian military was not designed for sustained offensive operations along the German model.

Throughout the 1930s, the leadership of the Romanian military designed its forces and theories around a national defense strategy. This strategy led to the general staff creating a circular defensive line intended to defend against Romania’s primary enemies, Hungary and the Soviet Union. Prior to the war, one of Romania’s leading military theoreticians, General Alexa Anastasiu, wrote that the “policy of our country is not aimed at a conquering war.”

With the defeat of Britain and France in 1940, Romanian leaders realized that they had to modernize their air force and armored units. However, time and Romania’s lack of financial and industrial resources limited the extent of modernization.

The Romanian military had other limitations as well. The German soldier of World War II was on average, well educated, highly trained, well equipped, and well led. The Romanian soldier by comparison was poorly educated, poorly equipped, and sometimes poorly led. Part of the problem was that approximately half of the educable Romanian population was illiterate. Romania was an agrarian nation, and approximately 75 percent of Romanian conscripts were peasants. As a result, many Romanian soldiers suffered from extreme fear of armored attacks as they had spent little time around mechanized vehicles.

Leadership was also a liability in the Romanian Army. Unlike the Wehrmacht, the Romanians did not have a strong noncommissioned officer corps. While members of the German officer corps generally had a close relationship with their men, the opposite was true with the Romanians. German officers often noted that their Romanian counterparts seemed to care little about the well-being of their troops, but instead treated them like vassals. One German soldier noted that the Romanian field kitchens prepared three different meals: one for the officers, one for the NCOs, and one for the enlisted.

The German Army trained a few of the Romanian divisions, and these units usually performed at a much higher level than the Romanian divisions that were not German trained. The Romanian soldier was not without admirable qualities. Perhaps because of his peasant background, the Romanian soldier was an excellent marcher, often covering distances that seemed remarkable to his German counterpart. But because of his cultural and educational background, the Romanian soldier had limited capabilities.

Romania’s Failed Rearmament Program

Perhaps the greatest limitation of the Romanian Army was a lack of modern equipment, a limitation of which the Germans were acutely aware. During the fighting around Stalingrad, German Maj. Gen. F.W. von Mellenthin inspected some Romanian Third Army units that had been placed under his command. He observed: “The Romanian artillery had no modern gun to compare with the German and, unfortunately, the Russian artillery. Their signals equipment was insufficient to achieve the rapid and flexible fire concentrations indispensable in defensive warfare. Their antitank equipment was deplorably inadequate, and their tanks were obsolete models bought from France. Again my thoughts turned back to North Africa and our Italian formations there. Poorly trained troops of that kind, with old-fashioned weapons, are bound to fail in a crisis.”

In his memoirs, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein made similar comments about the Romanians, “… the Romanians, who were still the best of our allies, fought exactly as our experiences in the Crimea implied they would.” Although the Romanians fought bravely against the Russians, bravery alone was no match for Soviet T-34 medium and KV-1 heavy tanks.

The Romanians had begun a rearmament program in 1935 in an attempt to upgrade their World War I-era equipment. The biggest challenge facing the Romanians in this effort was the absence of a Romanian armaments industry. This situation forced Romania to acquire most of its weaponry abroad, which led to standardization issues. Despite the rearmament efforts, when Operation Uranus fell upon the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies some Romanian soldiers were fighting with the same weapons their fathers had used in World War I.

In virtually every aspect, the Romanian Army lacked the proper preparedness for modern warfare on the Eastern Front. The Romanian soldier did not want to fight deep inside Russia. Lacking proper training, leadership, organization, but most of all modern equipment, the Romanian Army had little chance to survive.

Issues With Command and Control

The most serious operational problem for the Axis at Stalingrad was an untenable command-and-control situation. Army Group B was the main Axis force fighting in and around Stalingrad. It consisted of eight separate armies, specifically the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies, the Italian Eighth Army, the Hungarian Second Army, and the German Second, Sixth, Fourth Panzer, and Sixteenth Motorized Armies.

Manstein addressed this problem in his memoirs. “No army group headquarters can cope with more than five armies at the outside,” he said, “and when most of these are allied ones, the task invariably becomes too much for it.”

The Germans recognized the problem in the autumn of 1942 and proposed to remedy the situation by creating a new army group by dividing Army Group B. The new army was to be called Army Group Don and placed under the command of Romania’s Marshal Antonescu. However, Hitler insisted on the capture of Stalingrad before creating the new army. Thus, when the Soviet avalanche fell on the Romanians on November 19-20, Army Group B had the difficult task of controlling eight armies that spoke four different languages. To make matters worse, in October 1942 Hitler issued a bizarre order that armies were not to liaison with their neighbors in the line.

An inadequate supply system was another huge problem for Army Group B. The supply line to Stalingrad relied on a single railroad crossing over the Dneiper River. This single line supplied Army Group A fighting in the Caucasus and most of Army Group B. Only six pairs of trains per day could traverse this rail system. The supply of the Romanian armies was a low priority, as most material carried over this rail line went to the Germans fighting inside Stalingrad. The Germans also failed to deliver food, fuel, ammunition, and supplies to build defensive positions in the quantities promised, placing the Romanians in an untenable position.

The T-34: An Invincible Adversary Against the Romanians

The Germans also failed to ensure that an adequate reserve force backed up the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies. The Third Army was supported by the XLVIII Panzer Corps. This reserve force consisted of the German 22nd Armored Division and the Romanian 1st Armored Division. When the Soviet offensive fell on the Romanian Third Army, the 22nd Panzer Division had 104 tanks. As the division moved toward the front to halt the Soviet advance, tanks began to catch fire and stop running. The Germans quickly found the problem. In an attempt to keep their tanks warm, the Germans had placed straw in and around them. Russian field mice, also trying to stay warm, invaded the tanks and chewed on the electrical wiring. The Russian mice reduced the 22nd Panzer Division to 42 operable tanks and antitank guns.

The Romanian 1st Armored Division consisted mainly of 84 Czech-built R-2 tanks and 19 German Panzerkampfwagen IIIs and IVs. The R-2s were completely obsolete by November 1942. In October of that year, the Romanian 1st Armored Division conducted an exercise in which R-2s test-fired their 37.2mm guns into captured Russian T-34 tanks with no effect. The guns were totally incapable of penetrating the armor of the T-34s. When the massive Soviet attack came, the reserve XLVIII Panzer Corps had little chance of reversing the tide.

Prior German knowledge of the superiority of the Soviet T-34 makes the German inaction even more difficult to understand. In 1941, on the second day of Operation Barbarossa, the Germans began running into the Soviet T-34 in combat. The T-34’s thick armor and sloped design made it impervious to the German 37mm antitank guns. The Soviet KV-1 heavy tank carried even thicker armor than the T-34 and was even more difficult to destroy.

By November 1942, the Germans had 17 months of experience fighting T-34s and KV-1s. The Germans were well aware of their capabilities and which antitank weapons could and could not destroy these Soviet tanks. The Germans did take some small steps to rectify the Romanian antitank problem. Realizing that the Romanian guns could not stop the T-34 or KV-1, the Germans gave the Romanians some heavier 75mm antitank weapons. But the number of 75mm guns provided by the Germans amounted to only six weapons per Romanian division. Since each division of the Third Army had to cover a 20-kilometer front, this equated to one 75mm antitank gun for every three kilometers of defensive line.

A Failure in German Intelligence

Two of the Germans’ greatest errors were made when they ignored the warnings and requests of their Romanian allies. The Romanian Third Army sat dug-in on the south bank of the Don River, with the exception of Soviet bridgeheads at Serafimovich and Kletskaya. At Serafimovich, the bridgehead was six miles deep, which allowed the Soviets to bring in reinforcements outside of artillery range. The Soviets had launched an offensive across the Don in August 1942, and although the offensive had been halted by the Axis, the bridgehead was not completely reduced.

These bridgeheads, approximately 100 miles from Stalingrad, created a dangerous situation for the Romanians. Because the Romanians lacked sufficient antitank weapons and had no armor in the front lines, the Don River served as a tank obstacle in case of a Soviet armored attack. In October 1942, the commander of the Romanian Third Army pleaded with Army Group B for help in reducing the two bridgeheads. The Romanian commander argued that his troops could maintain their positions only if they held the entire southern bank of the Don River. While his German allies expressed sympathy to his position, they responded that nothing could be done until Stalingrad fell, an event they believed was imminent.

In what amounts to one of history’s biggest intelligence failures, the German intelligence service on the Eastern Front, Fremde Heere Ost, ignored overwhelming evidence of an impending attack. Some of the evidence came in the form of information from Russian deserters who told their interrogators of the buildup of Soviet divisions both north and south of Stalingrad. German intelligence officers forwarded reports with this information as well as reports of visual sightings and radio intercepts. Luftwaffe Col. Gen. Freiherr von Richthofen repeatedly warned his superiors of aerial reconnaissance sightings of the Soviet buildup opposite the Romanian Third Army, but to no avail.

Richthofen even noted in his diary on November 12, one week before the attack: “The Russians are resolutely carrying on with their preparations for an offensive against the Romanians.… Their reserves have now been concentrated. When, I wonder, will the attack come?… Guns are beginning to make their appearance in artillery emplacements. I can only hope that the Russians won’t tear too many big holes in the line!”

Probing Attacks Against the Romanians

Throughout October 1942, the Russians made repeated probing attacks out of their Don River bridgeheads. These attacks were obvious attempts to test the Romanian defenses and expand the bridgeheads. On November 2, German aerial reconnaissance photographed several new bridges over the Don River into the Serafimovich bridgehead. The Germans even identified a division of the Soviet Fifth Tank Army, previously thought to be farther north in the Orel sector, in positions opposite the Romanian Third Army.

To the south of Stalingrad, the Romanians were also reporting a buildup of Soviet forces in a bridgehead over the Volga River known as the Beketovka Bell. Despite this information, German intelligence was convinced that any Soviet attack would fall on Army Group Center to the north.

On November 12, one week before the start of the Soviet offensive, Fremde Heere Ost surmised that if the Soviets tried anything of an offensive nature it would be a limited operation against the Romanian Third Army. Two days earlier, the Romanians estimated that their Third Army was facing four armored divisions, two or three motorized divisions, seven to eight infantry divisions, and 40 artillery battalions. The Romanians correctly assessed their troubling predicament and warned their German allies, but with their focus completely on the capture of Stalingrad, the Germans ignored the warnings.

The last and most ominous warnings came on the evening of November 18 when the Romanians reported hearing hundreds of Soviet tanks starting their engines. Visual sightings of Soviet troops in the Serafimovich and Kletskaya bridgeheads drawn up in formation behind armor and thousands of artillery pieces on the move were also reported, but by this point it was too late for the doomed Romanians.

After November 19, remnants of the Third Army, known as the Lascar Group because they were led by the Sixth Division commander, Mihai Lascar, formed a defensive hedgehog and repelled repeated Soviet attacks. The Romanians requested permission to break out of the encirclement while they still had the strength to do so. Hitler continuously rejected these requests until several days later, when he relented. At this point, however, a full-scale breakout was no longer possible. Only a handful of the men of the Lascar Group eventually made it back to Axis lines.

Afterward, the Romanians did not hesitate to express their displeasure to their German allies. On November 25 at a German-Romanian meeting in Rostov, the Romanian Army chief of staff, General Ilie Steflea, expressed his anger to the Germans, stating, “All the warnings, which for weeks I have been giving to the German military authorities—to Supreme Command, to General v. Weichs and General Hoth and the head of the German Military Mission—have passed unheeded. My warnings that the Romanian forces had been allotted too broad a front have all been in vain, and in fact, the enemy has succeeded in breaching the line only at those points where battalions have been called upon to hold a five- or six-kilometer front … I repeated my warnings to Fourth Panzer Army … I warned General Hoth on all these points in good time when he visited the Romanian forces.… German Army headquarters failed to meet Romanian requirements, and that is why two Romanian armies have been destroyed.”

In short, the Germans failed to listen to the urgent warnings of the Romanians, and as a result both the Germans and Romanians paid a terrible price. Manstein’s “best of allies” were now angry and bitter about the catastrophic losses they had suffered.

“We Attacked the Enemy’s Weakest Point”

In dealing with their Romanian allies, the Germans made numerous unnecessary mistakes. To protect their vital flanks outside Stalingrad, the Germans positioned the Romanians even though they were incapable of withstanding a Soviet armored offensive. The Romanian Third and Fourth Armies were assigned defensive positions that they did not have the manpower or armament to defend. They were put in these positions after continuous campaigning in the Crimea, which left some units at less than 50 percent strength.

The Romanian request to reduce the Soviet bridgeheads over the Don and the Volga were denied. Despite signs that an attack on their flanks was imminent, the Germans ignored the repeated warnings of the Romanians and their own troops. Even without the warnings, a study of the map would have revealed that the Romanian armies were in danger. A Sixth Army operations officer, Captain Winrich Behr, received a prediction from the officer he replaced in October 1942. Behr was shown a situation map, and the officer traced the expected lines of a Soviet attack, then pointed to Kalach and said, “They will meet around here.” If a company-grade operations officer could read a map and foresee the coming catastrophe, certainly generals and field marshals could do the same.

After the war, Manstein was interviewed by his Allied captors and questioned about the German victory over France in 1940. Manstein responded, as if surprised at the inquiry, “We just did the obvious thing, we attacked the enemy’s weakest point. The hopeless French reconnaissance won us the Battle of France.” In one of the great ironies of military history, the Soviets followed this simple strategy and did to the Germans what the Germans had done to the French two years earlier. Why the Germans did not recognize their predicament and take appropriate action is inexplicable.

Romania Changes Sides

The destruction of two Romanian armies at Stalingrad increased the unpopularity of the war in Romania and exacerbated the already strained relations between the Romanian and German militaries. By August 1944, the Soviet Army had advanced to the eastern borders of Romania. Antonescu begged Hitler to allow the German and Romanian armies to abandon their positions in Bessarabia and pull back to a more defensible line incorporating the Danube River and the Carpathian Mountains, but Hitler refused.

When the Soviets launched an offensive in August 1944, the Romanian and German armies were quickly driven back. The reaction in Romania was swift. Two days into the Soviet offensive, Romanian government and military officials deposed Antonescu, seized control of the government, sued for peace with the Soviet Union, and then declared war on Germany.

The battle for Romania cost the Germans 250,000 men. With the Romanians now fighting at their side, the Soviets advanced quickly across Romania and into Yugoslavia and Hungary, sealing the defeat of Germany in the Balkans. Although the Romanians did not switch sides until 1944, the seeds of the defection were sown in 1942 with the mishandling of the German-Romanian alliance on the banks of the Don River.

Great help, very complete thanks for all your hard research. Stay safe. I’m writing a historical fiction novel .if you know of any WWII historians. In the palms springs ca. Area please let me know. God bless

In general you was accurate but some points are far from the reality. ”some Romanian soldiers were fighting with the same weapons their fathers had used in World War I.”-that was not true, the infantry weapons were comparable with other military forces from the continent! soldiers had 7.92 ZB24 rifles (comparable, in fact almost of copy of German K89), LMG ZBvs30 (many build under license in Romania-so was a weapons industry too!), MG were also ZB 53. Their real problems were antitank guns which were 37 mm and 47mm, both useless against T34. Even the 5 or 6 75mm guns the Germans provided were tested by Romanians before the attack and show limited effectiveness.