By Colonel James W. Hammond, Jr.

For decades Americans have been spoiled by the instant coverage of war in the media. The stark reality of Vietnam entered homes with the evening news. A plethora of military experts, including many retired senior officers, analyzed every nuance and possibility of American and Allied actions both before and after the jump-off against Iraq in the desert war. Front pages of newspapers reported the carnage of the “highway of death” as the Iraqis retreated from Kuwait. Americans have come to accept almost “being there” when the nation’s armed forces are committed. Such was not always the case.

An excellent example of the fog of war is the media coverage of the fighting in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands during 1942-1943. Instead of being covered by a host of reporters, each competing to be heard or read, there was scant coverage of these events. The fog of war was as literal as it was figurative. Actual visibility was shrouded by poor weather. Information visibility was clouded by a lack of press on the scene, other wartime events of greater significance to editors, or official press releases designed to buoy sagging morale without providing valuable information to the enemy. It was fertile ground for rumor and speculation, both of which found their way into the media. When the fighting in Alaska and the Aleutians was over, the war moved on.

News was delayed, censored, and incomplete, while Americans knew comparatively little of what really happened during fighting on their own soil.

“War Comes Closer to Home.”

On Thursday, June 4, 1942, the front page of The New York Times published an ominous box with the heading, “Coast Radios Silenced.” The Fourth Army Fighter Command in San Francisco had ordered all radio stations off the air lest they guide unidentified aircraft (later found to be friendly) to western cities.

A battle was raging at Midway 1,100 miles west of Hawaii. Another component of the Japanese offensive against Midway was taking place several thousand miles to the north. To Americans, the two widely separated actions seemed like a spectacular wide-front advance of the yet unbeaten enemy. To some newspapers, however, they were two distinctly different events. The action to the north of Midway was a daylight raid on Dutch Harbor in the territory of Alaska. A terse Navy release said, “… no further details at this time.”

The San Francisco Chronicle, while filled with news of Midway, told of the attack on Dutch Harbor, warning, “War comes closer to home.” It said the Alaska attack was no surprise. Hanson Baldwin of The New York Times also thought the actions at Midway and Alaska were not unexpected inasmuch as they were retaliation for the April air raid on Tokyo by Jimmy Doolittle, which had been launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. Baldwin felt that Dutch Harbor was merely a feint.

The next day, headlines proclaimed the victory at Midway and a Navy denial of another Dutch Harbor raid. Another radio blackout on the West Coast was reported as well, with Seattle being on a full war footing because of Dutch Harbor. No Navy releases were issued, and the absence of reporters in the formerly quiet Alaska sector caused the press to speculate that Dutch Harbor was a ploy to draw U.S. forces away from Midway. Many West Coast residents were convinced that they were next to be attacked following Dutch Harbor.

The most sensational story of all was published in the Chicago Tribune and reprinted in the San Francisco Chronicle. It said that the Navy knew of the Japanese plan and was waiting to meet the main Japanese force at Midway. Since the main thrust was known to be at Midway, American forces concentrated there and Dutch Harbor was ignored. Senior Navy commanders were enraged that such a story should appear but were compelled to maintain silence to avoid potentially compromising the fact that code breakers had cracked the Japanese naval code and were aware of the enemy’s intentions.

“Silence Shrouding Fight in Aleutians”

Given the paucity of reporters on site, the Navy obsession with secrecy and the other significant events worldwide, news from the Aleutians was sketchy. What appeared in the newspapers and aired over the radio emanated from Washington and came from Army and Navy releases subsequently distributed by the wire services to their subscribers. Thus, the public, no matter what its access to news, was being fed the same information throughout the country. The wire services also picked up broadcasts from enemy sources. Americans dismissed most of these as propaganda, but this was not always so.

On June 9, Berlin radio said Japanese forces had occupied islands in the western Aleutians. The Japanese then announced their occupation, which drew a Navy denial: “None of our inhabited islands are troubled with uninvited visitors at this time.” The Japanese were claiming that the Dutch Harbor raid had destroyed bases posing threats to Japan and that the Midway operation had prevented U.S. reinforcement of Alaska.

Press speculation said that the Aleutian fog could be hiding Japanese forces. It raised a question of an attack on Russia. It assumed that all inhabited islands in the chain were defended. On June 13, the Navy admitted the Japanese landings on Attu and Kiska, saying that weather had delayed verification. Japanese forces were on Attu and ships were in Kiska harbor. A headline the next day was timely and prophetic: “Silence Shrouding Fight in Aleutians.”

The Army reported that its aircraft were trying to dislodge the invaders. The Navy called the landing “face saving.” The press speculated it was a toehold for future attacks on the mainland, while Alaska’s congressional delegate warned against complacency toward this invasion of American soil.

“Too Little and Too Late”

The Navy was not being complacent. It reported that an air attack had damaged six warships, including three Japanese cruisers, asserting that the action was a smaller version of the Midway victory but pragmatically noting, “The general situation in the Aleutians remains unchanged.”

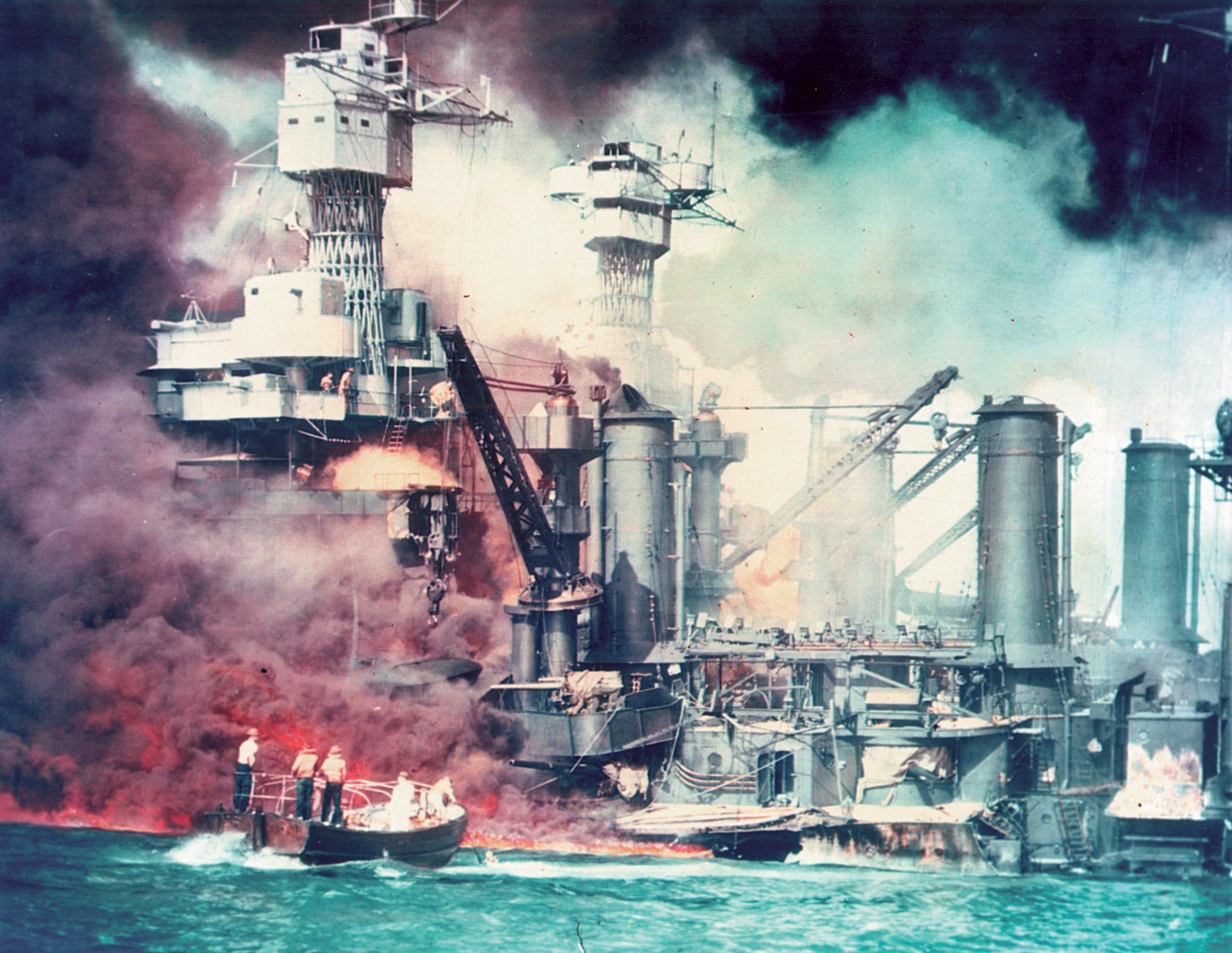

In discounting the menace, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson told the press that the enemy had only small forces in “one of the cloudiest places in the world.” He asked for patience: “I appeal to you for charity toward a communiqué under such circumstances.” The Japanese, having missed their opportunity to destroy the oil tank farm at Pearl Harbor, gloated over their destruction of the oil tanks at Dutch Harbor.

On June 20, a Navy statement said the enemy forces would be dealt with when the fog lifted. “The so-called mystery of the Aleutian battles is merely a mystery of weather, of fog, and snow coupled with a desire to keep the enemy in the dark. If the public is confused about the situation in western Alaska then so is the enemy—that is all to the good.” The assurances that Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, was not surprised by the attack did not allay the fears of people on the West Coast who considered the possibility of air raids from Japanese planes based in the Aleutians very real. Ten days after the fact, the Navy announced that Kiska and Attu had been occupied on June 12.

The lack of information caused problems that were fed by press speculation. Kiska could become a Japanese submarine base astride the Lend-Lease route to the Soviet Union. Its recapture could provide a submarine base for U.S. forays into Japanese waters. The once-ignored Aleutians were assuming huge importance in the press.

Senator D.I. Walsh (D-Mass.) of the Naval Affairs Committee defended the Navy policy of withholding information about the fight in the fog. “If the information given to this committee could be made public, which cannot be done without giving information to the enemy, the people would realize that with the vast problems confronting the Navy and with the tools and equipment [it] possesses at this time, there would be every reason for gratification for what has been done to date.”

The New York Times was still unhappy with the inaction when Hanson Baldwin editorialized at the end of June: “It is not weather alone that shrouds the Islands in fog. An obscurity of official comment also veils them.” He cited four instances. First, there were no “inhabitable” islands occupied. Then, it was a “face-saving” operation. It was just another experience of “too little and too late.” He rejected the excuse that the terrain was too rugged to benefit the Japanese.

Underplaying the Japanese Threat

During July and August, Navy and Army press releases reported air strikes as weather permitted. On August 1, the Navy release estimated about 10,000 invaders in the Aleutians but denied the rumor of a landing in the Pribilof Islands. On August 9, a Navy release said a surface task force had shelled Kiska. It implied that enough shipping had been in the harbor to justify an attack, but it added, “Nothing further is known about the results of the attack on Kiska.” Amplification a few days later said U.S. cruisers and destroyers in a bombardment “over the weekend” had damaged a destroyer and wrecked ground installations. The press provided twin assessments of the surface attack. First, the attack was to gain information because aerial reconnaissance was so poor in the fog. Second, Japanese airfields were not yet completed because the Navy would not risk surface ships under the threat of attack by land-based aircraft.

On August 20, the Navy claimed the sinking of a Japanese destroyer or light cruiser by a U.S. submarine and the downing of three Japanese planes. Three days later the Navy released a summary of Japanese ships sunk in Alaska since June.

Official releases during the autumn continued to minimize the Japanese threat and to point out the peril facing the Japanese garrison. It had inadequate supplies. The Navy attack on Kiska was costly to the Japanese at no loss to the United States. Then, U.S. counteraction was announced at the end of September. The Army had landed in the Adreanof Islands and built an airfield close to Kiska. The Japanese were pulling back.

The Navy announced, “Withdrawal from Attu and Agattu several weeks ago is indicated. There were no signs of enemy from aerial reconnaissance.” But there was bad news too. Several days later the Navy said that new buildings on Kiska indicated reinforcements. A submarine base was reported there. In late November, activity was discovered on Attu revealing that “apparently Japanese float planes returned to Attu after abandoning it earlier.” One year after Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester Nimitz, the U.S. Navy commander in chief in the Pacific, promised ouster of the Japanese from the islands. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox told reporters, “Only dead Japs will remain permanently in the Aleutians.” Lack of shipping was reported to have stranded the Japanese garrison on Kiska.

“The Battle of the Fog”

The new year brought bad news from the Navy. Float planes had reinforced Kiska, and apparently the Japanese had no intention of giving the island up without a fight. Their planes attacked U.S. ships and bases. In early February, the U.S. Navy reported its surface units of unspecified type were operating against the enemy and cited the float plane usage as an indication that no airstrips existed. On February 21, Navy warships shelled Attu in the first surface attack since August.

During March the Navy was silent, but the Associated Press broke a story contradicting the float plane theory. It said that an airstrip had been under construction on Kiska for a month. At the end of the month, the Navy made a cryptic comment about a surface action between ships west of Attu. After encountering an American force, four Japanese cruisers and four destroyers had retired west from Attu. There was no elaboration, and details would be revealed “when such information will not be of value to the enemy.” The press thought the appearance of a formidable enemy force was a surprise and was either escorting a convoy to Kiska or was the prelude to further naval involvement.

Two weeks later the Navy admitted there was airfield construction on Kiska and Attu. A long fighter strip was being laid out on Kiska and a longer bomber strip on Attu to the west. It was restated that the Navy had turned back a convoy on March 28. Fliers still reported operations hampered by weather, but more antiaircraft fire indicated an increased Japanese presence.

During the first week in May, details of the March surface action were released. A story by a reporter aboard one of the ships had a dateline of March 26, 1943 (Delayed), giving an eyewitness account of the battle. More news was coming out of the Aleutians. The Navy reported unopposed American landings on Adak and Amchitka, which had taken place in January. There were now U.S. air bases just 70 miles from Kiska.

More good news, although tardy, was released. Four days after the fact, the Navy revealed that Attu had been assaulted on May 11. U.S. progress was satisfactory and “details would be released as the situation clarifies.” Banner headlines proclaimed the “Battle of the Fog” as reporters with the landing forces filed stories. Secretary Knox defended the secrecy and delay in revealing the invasion. He reasoned that the Japanese were surprised and the delay in giving out details was “sound.” The battle ashore raged for a month. Daily reports of the fighting were printed as they cleared the censors. A running account of the battle appeared every day until the island was declared secure.

“Kiska Is Reoccupied, Japs Flee Without a Battle.”

The press speculated that Japan “apparently intends to let the Aleutians go by default.” This was based on a Navy release that no resupply attempts to Kiska had occurred since the sea battle in late March. The Navy noted also that the abundant salmon in Kiska’s streams could keep the Japanese from starving.

The fog in July held up raids on Kiska. Surface ships shelled the island in preparation for an assault. On July 7, Japanese shore batteries did not reply. Three days later fire was returned from shore. During the shelling on July 12, four Japanese ships were reported hit. Three days later, the enemy was silent, “as sometimes in the past.” Navy releases reported constant raids and shelling through July and then went silent on reports at the end of the month.

On August 22, during the Quebec Conference, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that American and Canadian forces had landed unopposed on Kiska on August 15. The official statement was brief. The Navy release was lacking in details, saying that the landing force had found that the enemy had fled in the fog. It assumed that the capture of Attu, astride the line of communications, had made Kiska untenable.

The Navy was unaware of the evacuation since bombing “had apparently destroyed Japanese radio equipment on Kiska.” It had assumed that the isolated garrisons “were not in contact with the homeland.” Thus, no release about American operations had been made since July 31. During daily bombings, the last antiaircraft fire had been observed on August 13. The landing took place on August 15, and the size of the landing force was not revealed. The Navy thought that evacuation had begun after Attu fell.

A reporter speculated that the Japanese garrison had evacuated in large submarines. Air reconnaissance had reported gradual abandonment of the main camp, but it was assumed that enemy troops were digging in in the hills. The initial landing waves were thought to have surprised the enemy, but as the troops moved inland they became suspicious that the enemy had gone. In hindsight, it was noted that barges had begun disappearing in July but a voyage to Japan in such craft was believed out of the question. The Japanese later explained that their troops had departed in July “for action elsewhere.”

A banner headline told it all. “Kiska Is Reoccupied, Japs Flee Without a Battle.” As far as the press and the public were concerned the battle in the fog was over and it disappeared from the pages as more important events occupied the space.

Baldwin of The New York Times offered one postmortem on September 1. He noted, “all sorts of errors.” The Attu landing, he asserted, was confused and uncoordinated. He reserved his biggest blast for Kiska. It was a gross failure in elementary intelligence work. Fog covered the evacuation. It could have covered small amphibious reconnaissance parties in covert landings to determine enemy strength. Bombing had done little damage. It did not force evacuation. The enemy left when resupply became impossible and the position untenable.

The Battle of the Aleutian Islands: A Historical View

With that, the fog of war once more closed over the Aleutians and passed to the realm of the historian and historical research.

As Stanley Johnston had so indiscreetly said in reference to the Japanese occupation of Attu and Kiska, we knew they were coming. Admiral Nimitz in Pearl Harbor had read the messages containing the plans of the Imperial Japanese Navy and deployed his naval forces to meet them. Nimitz was aware of the impending Japanese reaction to the Doolittle raid on Tokyo in April.

Japanese reaction was a change in strategic planning. Previously, Japan’s aims had been to acquire the natural resources of the Dutch East Indies, eliminate the threat of Guam and the Philippines as potential U.S. bases in the Western Pacific, and remain secure inside a protective screen of occupied territory to await the Allied acceptance of a fait accompli. Japan would emerge as the dominant power in the Western Pacific and on the East Asian mainland. The Doolittle raid poked a hole in this theory of safety behind an inner defense perimeter. Hence, Japan decided to extend the perimeter to the east, southeast, and northeast.

The southeast extension was thwarted, in part, at the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May 1942. Although unable to penetrate around New Guinea to Port Moresby, the Japanese established a base on Tulagi in the lower Solomon Islands, later to extend to Guadalcanal. The expansion east and northeast was to occur in June and include occupation of Midway, 1,100 miles west of Hawaii, and of islands in the Aleutians. Kiska was to anchor the northern end of the new outer defense perimeter as well as to obstruct U.S.-Soviet military collaboration. Tactically, the strike at Dutch Harbor was to deliver a blow that would distract Nimitz from the forces approaching Midway and confuse him as to the location of the main attack on Midway. Another Japanese force lay between the Aleutians and Midway to destroy American forces that were shifted from one to the other.

Initially, Nimitz became aware of an impending major thrust but in April was not sure as to where or when. In Alaska, he suspected three Japanese objectives based on his own analysis. These were Makushing Bay, Cold Harbor, and Dutch Harbor. On May 21, 1942, Nimitz formed Task Force 8. Its commander, Rear Admiral R.A. Theobold, had heavy cruisers Indianapolis and Louisville; light cruisers Honolulu, St. Louis, and Nashville; and 10 destroyers. They were designated for duty in the North Pacific. Meanwhile, the code breakers had informed Nimitz that the main attack was to be at Midway. Nimitz correctly decided that the Aleutian operation was a feint. He did, however, inform Theobold of Japanese intentions to occupy Kiska and Attu. Nimitz knew that the Japanese Northern Area Force included the light carriers Ryujo and Junyo, heavy cruisers Takao and Maya, and three destroyers. He knew it would strike soon after June 1.

Postponing the Invasion

The Japanese launched their air strikes on Dutch Harbor early on the morning of June 3. Bad weather caused one group to return to its carrier. Another group of 12 made the initial raid. A second attack came across an airstrip at Otter Bay. It was surprised by U.S. Army fighters and lost four aircraft without finding Dutch Harbor in the fog.

The carriers had been discovered by a U.S. patrol plane before launching their first strike. While the Japanese were searching for Dutch Harbor, U.S. bombers were attacking the carriers but scored no hits. The sighting of the Japanese task force caused Theobold to speed to their reported position, but the Japanese had withdrawn.

The Japanese believed that American defenders were on Adak, Kiska, and Attu in strength. They planned to hit Adak by air before the carriers retired from the area to support the later landings on Attu and Kiska. If advantageous, a landing was also contemplated on Adak, but the presence of the airstrip at Otter Bay canceled the Adak landing. Weather also canceled the air raid on Adak. Better weather was forecast for Dutch Harbor, and the Japanese hit it again on the afternoon of June 4.

Meanwhile, disaster at Midway caused Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the combined fleet, to “temporarily postpone” landing there or in the Aleutians. The Northern Area Force was ordered south to cover the retirement from Midway. Four hours later, the order was countermanded and the invasion of the Aleutians rescheduled.

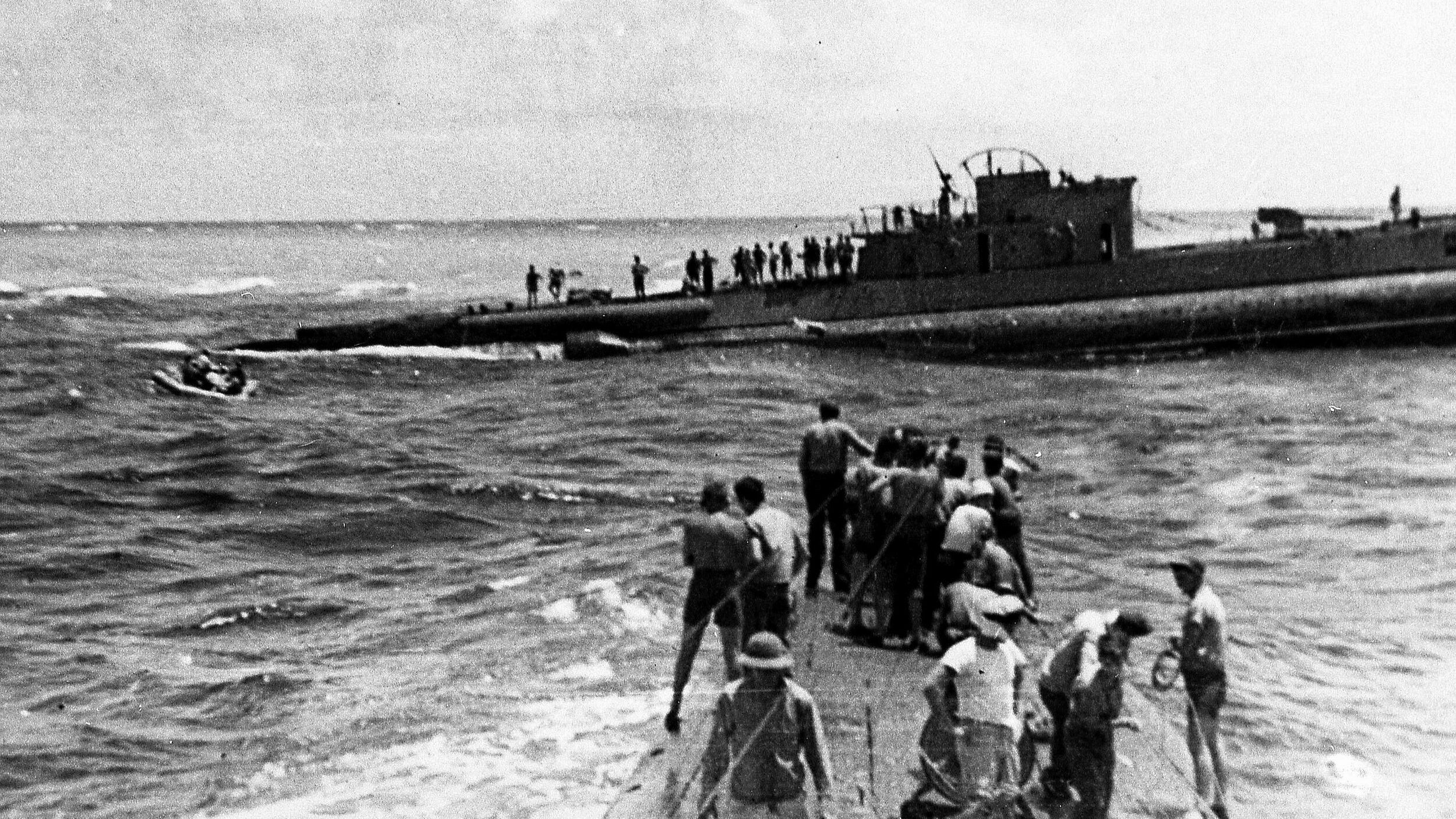

Landing on the Islands

The Kiska Occupation Force consisted of the light cruisers Kiso and Tama, the auxiliary cruiser Asaka Maru, and three destroyers. Five hundred marines of the Special Landing Force and 700 labor corps troops were in two transports. They assaulted Kiska expecting to fight a battalion of U.S. Marines. Instead, they found 10 members of a weather station team. The combined Attu-Adak forces consisted of the light cruiser Abukuma, five destroyers, the seaplane carrier Kimikawa Maru with six float planes, and two transports carrying 1,200 army personnel including construction troops.

Americans became aware that Attu and Kiska had fallen when weather reports were not received on June 8. Two days later, a patrol plane reported four enemy ships in Kiska harbor and tents on Attu. The campaign then settled into the fog of war. The Army flew missions against Attu and Kiska for the next two months. Half of them returned without finding targets because of poor visibility.

The Japanese did leave Attu on September 10, 1942, but went back late in October after reorganizing their Northern Pacific command. In the meantime, Americans were moving. Since the Japanese did not want Adak, the Army occupied it on August 30, 1942. An airstrip for fighters and bombers was built immediately to keep Kiska and Attu under attack. Another unopposed landing was made on Amchitka on January 9, 1943, and an airfield was built there.

The Japanese were moving too. Prior to the temporary abandoning of Attu, shipping had left Kiska in June after aircraft had sunk a transport. A seaplane tender moved her brood to nearby Agattu until the weather closed in on Kiska and that base could be developed safe from attack.

The summer weather had hampered surface engagements as well as air attacks. On July 21, 1942, Theobold, his flag aboard Indianapolis, left Kodiak. With him were Louisville, Honolulu, St. Louis, and Nashville plus five destroyers, four destroyer minesweepers, and an oiler. Approaching Kiska in a thick fog, they refueled from the oiler Guadalupe. Theobold postponed the bombardment of Kiska and retired eastward. He returned on the 27th, but again the fog was too thick. He canceled the mission and headed back to Kodiak. In the fog, two of the destroyer minesweepers collided. The destroyer Monaghan was also involved in an accident. The return of the task force was retarded by the reduced speed of the four damaged ships.

Theobold moved his flag ashore and turned Task Force 8 over to Rear Admiral William W. “Poco” Smith, who sortied with the same ships less the four damaged ones on August 3. They shelled Kiska on August 7. The cruisers catapulted spotting planes, but the enemy Mitsubishi Zero floatplane fighters kept them too busy to do their job. The ships fired indirectly with mediocre results. A freighter was set afire and later sunk. Barracks and barges were destroyed, as were three flying boats. Two destroyers, three sub chasers, and several midget submarines were unharmed. Several of the U.S. ships were slightly damaged by near misses from shore batteries. One spotting plane was lost, and all the others were holed by machine guns. The next bombardment did not take place until February 18, 1943. By then, more Navy surface units were available because of new construction and the easing of requirements for heavier ships and destroyers off Guadalcanal.

McMorris’ Initiative

In the interim, fog, wind, and weather were hard on the Navy. Four ships were lost. On June 19, 1942, the submarine S-27 grounded off Amchitka. On December 29, the destroyer minesweeper Wasmuth foundered in heavy seas. Two days later, the submarine rescue ship Rescuer grounded and was abandoned. On January 12, 1943, the destroyer Worden grounded and later sank.

In late March 1943, Rear Admiral C.H. McMorris, his flag aboard the light cruiser Richmond, in company with the heavy cruiser Salt Lake City and four destroyers, including repaired Monaghan, was west of Attu and south of the Komandorski Islands. McMorris was between the northern Japanese base at Paramushiro and the Japanese garrisons in the Aleutians when he ran into a powerfully escorted resupply convoy. Two transports and a slower freighter were escorted by the heavy cruisers Nachi and Maya, the light cruisers Tama and Abukuma, and five destroyers. Both Nachi and Maya were a few knots faster than their American counterparts, and their combined 20 8-inch guns were double the 10 aboard Salt Lake City. The Americans had radar, while the Japanese did not. However, in a daylight fight with good visibility, firepower could compensate. Still, McMorris decided to engage.

Here again was demonstrated the difference in naval philosophy between the Japanese and the Americans. American commanders were inculcated with the principle of exercising initiative in attacking enemy ships when the opportunity arose instead of slavishly adhering to prior orders issued without regard to a changing situation. Boldness was the watchword. Japanese commanders were no less bold, but they usually did not disregard their original orders despite an opportunity for destroying the enemy. In this case, the mission of the Japanese commander was to protect the convoy. He fought the engagement with that handicap.

The battle opened on the morning of March 26, 1943, with the American column overtaking the convoy, which was sailing in column but tied to the speed of the slower transports. The Japanese warships turned east and then south toward McMorris to place themselves between the Americans and the transports, which continued northwest. The Japanese ships kept themselves north of the Americans during the fight, and the heavy cruisers concentrated their fire on Salt Lake City, which returned the compliment. During the almost four-hour engagement, Salt Lake City was hit at least four times. Nachi, the Japanese flagship, was hit early in the fight, and both Japanese heavy cruisers took several hits. The fight ended at noon, 60 miles west of where it began, with the Japanese headed away to the west and home while Salt Lake City was dead in the water and taken under tow by Richmond.

The Japanese succeeded in protecting the convoy, but the convoy did not get through to Kiska and returned to Japan. The damaged U.S. ships returned home across the international date line on the same day they had won the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. This was the March sea battle whose report had been delayed by the Navy in Washington.

Taking Attu

A week later, the U.S. 7th Infantry Division stormed ashore on Attu. The Navy was there in force to support the amphibious landing. Operation Landcrab was under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kincaid, who also commanded Task Force 16. Shore-based Army air units, Navy patrol squadrons and submarines, and two covering groups were part of Task Force 16. The Southern Covering Group, Task Group 16.2, included the light cruisers Raleigh, Richmond, and Detroit and five destroyers. The Northern Covering Group, Task Group 16.7, was more powerful with the heavy cruisers Wichita, San Francisco, and Louisville plus four destroyers. The assault force, Task Force 51, under Rear Admiral F.W. Rockwell, softened up the beaches for the troops. Its muscle included three battleships, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Idaho. The escort carrier Nassau had 26 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter planes. Eight destroyers screened the force and provided fire support to the battalions on the beach. The fight ashore lasted until the end of the month.

With Attu gone, Kiska was isolated. Task Group 16.7 conducted the first bombardment of Kiska in almost a year on July 6, 1943. The shelling lasted 22 minutes, and no return fire was received.

A bigger bombardment was scheduled for July 2. Task Group 16.7 waRetired U.S. Marine Colonel James W. Hammond, Jr., is a veteran of the Vietnam War who also served as Plans Officer, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. He resides in Reno, Nevada. again to take part, but the battleships Mississippi and New Mexicowith the heavy cruiser Portland and several destroyers were to provide the big punch. No return fire was directed at the ships. A half hour after the ships retired, Army fighters and medium bombers attacked Japanese targets. One U.S. fighter was shot down.

The Battle of the Blips

On Sunday, August 15, American and Canadian troops waded ashore on Kiska. There was no enemy to fight. The Japanese had evacuated more than two weeks earlier. What had led to this blunder, which repeated that of the Japanese 15 months before when they expected to find Marines but found only a weather crew? Had American intelligence, with its interception and decoding of Japanese message traffic, failed?

After the loss of Attu and the turning back of their reinforcement effort at the Komandorskis, the Japanese deemed Kiska untenable. Thus, on May 26, even before the firefights on Attu, they began to withdraw the Kiska troops. Large I-class submarines had been running the blockade submerged and delivering a modicum of supplies. Each could take out 60 men on return. Of the 13 boats used in this way, four, I-9, I-24, I-31, and I-7, were sunk by U.S. destroyers and a sub chaser most likely guided by decoded intercepts. Three other I-class submarines suffered damage or scraped bottom in Kiska Harbor and had to turn back. The Japanese canceled the submarine evacuation after removing only 820 men.

The Japanese were faced with the dilemma of either trying to breach the surface blockade or leaving their troops to fend for themselves. The U.S. Navy controlled the approaches to Kiska and with radar in its 1943 state could satisfactorily detect any surface incursions.

It was radar that was to provide the help the Japanese rescue effort needed. On the evening of July 25, the battleships Mississippi and Idaho with the heavy cruisers San Francisco, Wichita, and Portland and an escort of destroyers was southwest of Kiska barring any approach to or retirement from there. Just after midnight, the battleship radar reported mysterious blips less than 15 miles distant. The U.S. ships went to general quarters and opened fire. The shell splashes created more blips, and firing continued for half an hour until the radar screens were clear.

A daylight search of the target area found nothing. Evidently, inexperienced radar operators, abetted by officers unfamiliar with the new electronics, misread reflections from nearby islands as targets. Remarkably, neither the San Francisco nor any of the destroyers, all ships with battle-seasoned crews, reported seeing the mysterious blips. The Battle of the Blips, which occurred on July 26, depleted the magazines of the task group as well as the oil bunkers. The ships left station for a refueling and replenishment rendezvous, opening the gate for the Japanese evacuation force.

The Japanese had made the decision to evacuate their troops in a bold move under the predicted fog. Cruisers and destroyers were to dash into Kiska, load troops, and head back to Paramushiro under the shroud of mist. The old light cruisers Tama, Abukuma, and Kiso with six destroyers were assigned the task. They would refuel en route before making the final run. While the fog hid them, it was not completely friendly. Two destroyers collided at the same time that the Americans were firing at phantoms, forcing one to return to Japan and the other to join the oiler’s screen.

At noon on the 28th, fog moved over the harbor while the ships made the final 50-mile dash. Troops were ready, their demolition charges set, and they were on board in less than an hour. As the fog lifted briefly, the 5,183 men in the cruisers and destroyers left to the sound of explosions ashore as the base was leveled by their charges. By the end of the month, they debarked at Paramushiro.

The feat remained a secret for three weeks. It is doubtful that it was really a secret among the highest echelons of the American command, particularly those who were privy to the breaking of the Japanese codes. But any action based on the knowledge of the evacuation would severely compromise the fact that the codes had been broken. Secrecy would also provide a convenient cover up of the embarrassing Battle of the Blips.

Uncontested, but not Bloodless

In the meantime, preparations for the Allied invasion of Kiska went ahead, but the rest of the Navy began to have some suspicions. A break in the fog after August 2 allowed aerial photoreconnaissance. This indicated greater destruction than previously noted. It was attributed to the 14-inch shells of the battleships and not the Japanese demolition. There was also the question of radio traffic after July 28. There had also been no return fire from shore batteries after the latest bombardment although Army aviators swore they had received fire during bombing missions after the 28th.

The Navy feared Japanese trickery and was wary that the enemy lay in wait for an invasion force. The haze over the island reduced the resolution of aerial photos. Radio silence deprived the radio interceptors of any clues, but in all probability the invasion went forward because cancellation could tip the Japanese to the fact that the Americans were already aware of the evacuation and that their communications had been compromised.

Major General Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, a Marine amphibious warfare expert, was an observer with the landing force. He distrusted the accuracy of Army aerial reconnaissance and wanted to send small amphibious recon teams ashore in rubber boats to determine the extent of enemy activity. This recommendation was discounted.

The troops landed and searched for two days before conceding that the enemy had vanished. It was not bloodless, however. Friendly fire resulted in about two dozen deaths and the same number of wounded.

The Battle of the Fog, and the Press at War

The occupation of the Aleutians wounded American pride and aroused indignation. Attu and Kiska posed such slight danger to the United States that they probably could have been ignored without affecting the outcome of the war. They were an example of press and public opinion influencing how the war was to be fought.

The Aleutians did become a base for harassing Japan. After September 1943, a series of air raids was delivered against Paramushiro. In February 1944, a striking force of light cruisers Richmond and Raleigh with seven destroyers shelled that base in the Kurile Islands.

The fact that the United States had cracked the Japanese naval code remained a secret for more than a generation, contributing to the perpetuation of the fog of war.

Retired U.S. Marine Colonel James W. Hammond, Jr., is a veteran of the Vietnam War who also served as Plans Officer, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. He resides in Reno, Nevada.

My Father was stationed on Attu from 12/43 to 12/45. He had nothing good to say about his time there. Cold, wind, fog and the only tree was fake!