By Eric Niderost

Major General Charles “Chuck” Yeager, United States Air force (Ret.), was one of a handful of people who could rightly claim the title “living legend.” He is best remembered as the first human being ever to break the sound barrier, a feat that some scientists claimed was impossible. Yeager achieved Mach 1 aboard the experimental Bell X-1, which he named Glamorous Glennis after his wife. The date was October 14, 1947, and his flight is considered a milestone in aerospace history.

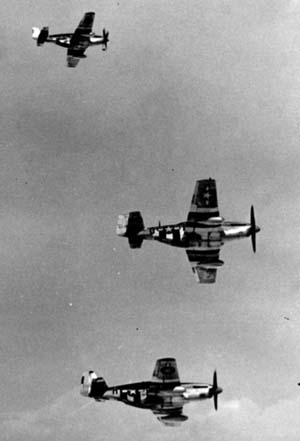

But Yeager’s much heralded feats as a test pilot in the 1940s and 1950s have obscured his World War II record, a record that equals—and perhaps surpasses—anything he ever did for the aerospace industry. He was a P-51 Mustang ace, fighting the Luftwaffe in the skies over Europe. Shot down, he managed to evade capture and successfully reached neutral Spain. Perhaps most remarkable of all, Yeager managed to return to combat, even though it was against official policy at the time.

An Excellent Marksman At An Early Age

Charles Elwood “Chuck” Yeager was born on February 13, 1923, in Myra, a small farming community in West Virginia. Later, when Chuck was about three or four, the family moved to Hamlin, a town of some 400 souls. The Yeager family and their neighbors were mountaineers for the most part, the kind of folk that outsiders ridiculed as “hillbillies.”

Though firmly rooted in the 20th century, Yeager’s childhood reads in part like Huckleberry Finn with a touch of young Abe Lincoln. Farm chores like slopping the hogs and milking the cow were part of the daily routine. Boys went barefoot in the summer and enjoyed hunting, fishing, or taking a plunge in the old “swimming hole.”

Chuck was the second of five children. His father, Albert Yeager, was a tough and honest man who eventually worked as a natural gas driller. A talented mechanic, he seemed to relish tinkering with his old Chevy truck and the generators and motors used in his drilling equipment. Young Chuck inherited this ability along with an almost insatiable curiosity about how things worked. These traits would stand him in good stead during World War II.

Young Yeager was also an experienced hunter and a crack shot, characteristics that would help him achieve success as a fighter pilot. He shot rabbits with a .22 rifle at age six, bringing them home to supplement the family’s food supply. By the time he was a teenager, steady nerves, keen eyesight, and great muscle control and coordination made him stand out even in a region where marksmen were commonplace.

But Yeager had a strong desire to see the world that lay beyond the craggy mountains and narrow hollows of rural West Virginia. When an Army Air Corps recruiter came by, young Chuck eagerly signed on for a two-year hitch. He was going to be an airplane mechanic. It seemed an obvious choice because he had natural talents in that direction. He was one of the few young men in the area who could take apart and reassemble an engine with amazing precision and real enthusiasm.

Ironically, he had no interest in flying at the time. He records that the first airplane he saw up close was a Beechcraft that had crash landed in a cornfield along West Virginia’s Mud River. It was a decidedly inauspicious encounter, and the experience left him unmoved.

A Young Mechanic in the Army Air Forces

Chuck Yeager enlisted as a private in the U.S. Army Air Forces on September 12, 1941, and was assigned to George Air Force Base at Victorville, California. His mechanical abilities and natural curiosity were so great he soon knew airplanes inside and out, right to the very last bolt. But there were some military duties that were not much to his taste, like guard duty and “KP.” Perhaps there was a way to escape such onerous assignments.

The young mechanic started thinking about becoming a pilot but discovered his relative youth and his educational background were against him. Pilots usually had a college education; Yeager was a high school graduate. But then Yeager saw a notice that announced a “flying sergeant” program. Once accepted, you would become a noncommissioned officer and a pilot to boot. This sounded like heaven to Yeager, a promotion and escape from boring duties like KP.

Rarely has a distinguished aviation career begun so casually or so inauspiciously. At this point the young cadet still had no real desire to fly. Indeed, it is a miracle he stayed with the program. His first fight was a disaster, with the would-be pilot becoming so violently airsick he threw up all over the cockpit. But Yeager slowly—and at times painfully—became used to flying. His natural abilities as a pilot, long dormant, came to the fore.

Rarely has a distinguished aviation career begun so casually or so inauspiciously. At this point the young cadet still had no real desire to fly. Indeed, it is a miracle he stayed with the program. His first fight was a disaster, with the would-be pilot becoming so violently airsick he threw up all over the cockpit. But Yeager slowly—and at times painfully—became used to flying. His natural abilities as a pilot, long dormant, came to the fore.

By his own admission, Yeager’s first solo flight was rough, and when he landed he bounced down the field like any other raw novice. But he improved rapidly, and after 15 hours in the air he was the best pilot in his class, so skilled his instructor assumed he had been an aviator in civilian life. But perhaps more importantly, he now loved flying. As Yeager says in his autobiography, “The joy of flying—the sense of speed and exhilaration … makes you so damned happy that you want to shout for joy.”

Earning His Flight Wings

By this time America was in the war, and the pressing need for pilots changed the rules. By the time Yeager got his wings, he became a noncommissioned flight officer. He graduated on March 10, 1943 and was assigned to the 357th Fighter Group at Tonopah, Nevada. The main equipment used was the Bell P-39 Airacobra, and the fledgling pilots were put through their paces from dawn to dusk, six days a week.

The P-39 was something of an odd duck, with some modern features wedded to strange engineering choices. The engine, for example, was mounted behind the cockpit. Its turbo-supercharger was not very efficient, which meant it was a failure as a high-altitude fighter. The British initially were interested in it but ultimately rejected the design. Among other things it was discovered that constant firing of the P-39’s 37mm cannon would produce deadly fumes that could fill a cockpit and actually threaten a pilot’s life.

Eventually, these problems were somewhat overcome, and the P-39 enjoyed a good reputation in Russian service in close-air support missions. Chuck Yeager and the 30-odd men of the 357th seem to have enjoyed flying the Airacobra, whatever its reputation. Out in the desert they were free to fly to their heart’s content, practicing strafing and dogfights hour after hour.

“Survival of the Fittest” For the Combat Pilots

Not all was lighthearted fun. Combat flying, even simulated combat flying, was a dangerous business, where poor judgment or poor skills or just plain bad luck could cost a pilot his life. In six months 13 men of Yeager’s group were killed, an accident/kill rate that was so high it nearly cost the 357th Group commander his job.

Yeager freely admits he did not mourn the pilots who crashed. In the Air Forces, the euphemism was they “bought the farm.” It was a process that was Darwinian, a classic case of “survival of the fittest.” While angered that these men wasted their lives through stupid mistakes, Yeager was not sorry to see them go. He reasoned rightly that poor fighter pilots would be the first ones to be killed overseas. And in real combat situations a stupid mistake might cost the lives of others, too.

Conditions were primitive in Tonopah, but the men did not care. They were housed in tarpaper shacks, the desert wind howled incessantly, and at night temperatures chilled to the bone. But to the men of the 357th, the skies were their real home, while the shacks were just a temporary place to sleep between flights.

For recreation Yeager and his buddies hit Tonopah, which was an old silver mining town. They patronized the Tonopah Club, drinking bourbon whiskey and rye until they could barely walk. For those who wanted further entertainment and were not too drunk to enjoy it, there was a stop at Madame Taxine’s, the local brothel. But soon the fighter group was ordered to California and then to Wyoming to complete its training.

It was in Casper, Wyoming, while staging simulated attacks on Consolidated B-24 bomber defensive boxes, that Yeager almost bought the farm. He was in mock attack mode, speeding in at 400 miles per hour, when suddenly the P-39’s engine exploded behind him. Flames shot in every direction as pieces of the plane detached from the fuselage. Yeager somehow managed to bail out, but the accident left him in the hospital with a fractured back.

A Hunter of the Skies

Yeager recovered, and before long the 357th got its orders to go overseas. The group departed the States on November 23, 1943, to join the Eighth Air Force. Its duties were varied, including strafing missions and escorting B-24 bombers. The 357th flew North American P-51 Mustangs, arguably the finest American fighter of the war. Yeager’s first mission took place on February 11, 1944, and today he candidly admits that the pilots were all scared to death.

It was a routine mission over the French coast, and though no German fighters came up to meet them they did have to go through heavy clouds of flak, the dreaded German antiaircraft fire. Even in those early missions there were periods of hair-raising adventure.

Chuck Yeager soon found he had all the qualities needed to become a top fighter pilot, including a hunter’s instincts, quick reflexes, and superb eyesight (his visual acuity was 20/10). By most accounts his first fighter was a P-51B, which he handled superbly. Yeager chalked up his first kill over Berlin, shooting down a Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter with relative ease. The 21-year-old pilot was living up to his name, since Yeager is an Anglicized version of the German Jaeger, meaning hunter.

Shot Down Outside Bordeaux

However, the fortunes of war can suddenly change. The next day, March 5, 1944, Yeager was himself shot down about 50 miles east of Bordeaux. It all happened so suddenly that, quick though his reflexes were, he hardly had time to react. A Focke Wulf FW-190 fighter got lucky, sending a steady stream of hot 20mm lead into Yeager’s Mustang. The American’s plane seemed to explode, the engine catching fire and spouting fingers of orange-yellow flame.

The burning Mustang began to roll, corkscrewing down to earth like a meteor. Yeager just managed to bail out at 16,000 feet but fought a natural desire to pull the ripcord and deploy his parachute. He knew that if he opened the chute too soon, it would take longer to descend to the ground and that would make him easy prey for German fighters.

After what must have seemed like an eternity, Yeager pulled the ripcord and floated down into a patch of heavily wooded French countryside. Once on the ground he took stock of his situation. Yeager had shrapnel wounds on his legs and hands and a deep gash in his forehead. He put some sulfa powder on his wounds and glanced over a silk map all pilots carried for occasions such as these.

Yeager was cold, scared, and probably in pain from his wounds, though perhaps the adrenaline that coursed though his body somewhat numbed the lacerations. He was in a tight spot, and he knew it. Yet, stubborn courage combined with the cockiness of youth to produce a curious optimism. He was a country boy and knew how to survive in a forest if he had to.

Yeager realized he was not out of the woods, literally or figuratively. Ever so often a German scout plane would circle like a bird of prey while he ducked for cover. They had not spotted him yet—or at least, he hoped not. For all he knew his position was already reported, and a German patrol might have been dispatched to pick him up.

“Me American. Need Help. Find Underground.”

Like all American fighter pilots he was armed with a .45 pistol, but Yeager knew he could not fight it out with a heavily armed German patrol. But there were two factors that gave him some reason to be optimistic: he was on French soil, and in southern France to boot. Neutral Spain was not that far away, relatively speaking, and if he could somehow make it across the Pyrenees Mountains he would be safe.

Yeager also knew it was good luck to be on French soil. There was a strong possibility he might make contact with the French Resistance. If he had been shot down over Germany, the chance of escape, at times even survival, was nil. German civilians had been increasingly angered by the incessant Allied bombing campaign, and downed pilots were sometimes killed on the spot.

The first night was probably the worst. The German planes stopped searching, at least for the moment, but a cold rain dampened Yeager’s spirits as well as his body. He chewed on a stale chocolate bar, a remnant of his survival kit, then tried to bed down under his parachute. Yeager dozed a bit, but for the most part was unable to sleep. Clutching his .45, the downed pilot stared into the inky void, ears straining to hear the possible approach of danger.

The next morning, cold, stiff, and tired from his nocturnal vigil, Yeager suddenly spotted a man nearby, a French woodcutter, but the axe the man was carrying looked formidable. The woodcutter had not seen him yet. Now, the fact that the man was not a German soldier was a step in the right direction, but Yeager still had to exercise caution. There were French collaborators, those who supported the pro-German Vichy government.

Yeager jumped the man and waved his .45 in the Frenchman’s face. The woodcutter did not speak English, so Chuck resorted to pidgin: “Me American. Need help. Find underground.” Though obviously scared of the pistol, the woodcutter seemed to understand the basic message. He let loose a stream of rapid-fire French, but Yeager got the basic premise. The woodcutter was going to get another man who spoke English and might help.

The woodcutter soon returned with a companion, an old man who declared, “American, a friend is here. Come out.” The old man was a guide, so Yeager followed him. The pair walked through the heavily wooded countryside, pausing ever so often to hear the muffled sounds of German voices echoing through the trees. German patrols were still scouring the forest for him.

Sneaking Into Nerac

The old man took Yeager to an isolated stone farmhouse in a clearing. The American was taken inside a barn then led up to the hayloft. The old man gestured to Yeager that he should enter a tool closet, and once the pilot was inside hay was stacked against the closed door. Later, Yeager heard German voices in the hayloft, possibly hunting for him. Yeager was dripping with sweat, his finger on the .45’s trigger.

The Germans finally left, and after a few hours in the stifling tool closet the old Frenchman came back for him. “They’re gone,” the senior reassured then took Yeager to the main farmhouse. It was owned by a middle-aged Frenchwoman who spoke perfect English. He was fed, and a local doctor treated his wounds. After he stayed in the hayloft for almost a week, the French doctor returned and told him he was going to be moved.

Yeager was given civilian clothes, complete with an axe strapped on his back, a common custom among French woodcutters. Transportation was by bicycle, and Yeager was given false identity papers if stopped by a German patrol. The pilot and the doctor had a pleasant two-day journey, finally arriving at a farmhouse in the village of Nerac. The place was not too far from Roquefort, famed for its cheese.

The farmhouse was owned by a Frenchman named Gabriel, a bluff and hearty Gaul who sported a big black mustache. Gabriel in turn led Yeager into the mountains, whose craggy peaks were carpeted by thick forests. It was there they met a group of heavily armed men in black berets. Yeager did not need an introduction. It was obvious they were a unit of the Maquis, or French Resistance.

There were 26 men in this particular group, all heavily armed with British Sten guns and Spanish .38 Llama automatics. It was only March, so no attempt to cross the Pyrenees could be risked until the snow from the upper peaks melted. Yeager would stay with the Maquis for a time, sharing their dangerous life until it was judged a good time to cross the mountains.

The Maquis “Fuse Man”

The Maquis lived a peripatetic life, constantly on the move to avoid German patrols. They would hide out in the woods and mountains during the day, emerging when darkness fell. Sometimes they would act as saboteurs, blowing up bridges or destroying German military trains. Other times they might ambush German patrols, turning the tables on their would-be pursuers. Yeager did not actually go out on any missions, but he did assist in other ways when he could.

Once, after a night supply drop from a British Royal Air Force Avro Lancaster bomber, some of the cargo was found to contain bundles of plastic explosives as well as timing devices and fuses. Yeager was familiar with such items, having helped his dad shoot gas wells with plastique explosives, and was happy to lend a hand. He showed his Gallic companions how to set up various timings for the explosives, and they were delighted. For the time he was with them, Yeager became a Maquis “fuse man.”

Yeager’s sojourn with the Maquis was risky in more ways than one. He was in civilian clothes, aiding and abetting a resistance group. That meant he was not protected by the rules regarding prisoners in the Geneva Convention. If captured, he would probably be turned over to the Gestapo for interrogation, torture, and ultimately execution by rifle or machine gun.

Germans Attack in the Pyrenees

Finally, it was deemed safe enough to travel over the Pyrenees. However, the concept of safety applied only to the weather, not other dangers. The border between France and Spain was heavily patrolled by the Germans, and the mountain passes and ravines would still be bitterly cold and choked with snow. Yeager found himself concealed in a truck along with three or four other Allied evader/escapees headed for the foothills.

Yeager was paired with another American named Pat, who had been part of a B-24 crew that had been shot down over France. Their French hosts supplied them with ample food and clothing for the journey; both men were young and strong and eager to set off. But they soon found their progress slowed by knee-deep snow, wet and viscous enough to make each step exhausting agony.

Soon they were forced to rest every 10 to 15 minutes, and a cold, biting wind chilled them to the bone. After a march of four days they started to wonder if they were lost. Just when they were at the limits of their endurance they bumped into an empty lumberman’s cabin. It seemed like a dream as they crumpled to the floor and slept.

But the dream turned into a nightmare when they were rudely awakened by German bullets whizzing through the cabin. A German patrol was just outside, but instead of attempting to capture the fugitives the soldiers unslung their weapons and opened fire. The Americans scrambled out of the cabin somehow, found a log chute, and rode down the flume before the Germans could react.

The two Americans slid down rapidly and were deposited in a cold but deep pond at the bottom of a hill. In other circumstances it might have been funny, but Yeager discovered Pat was seriously wounded. Pat was ashen and lapsed into unconsciousness, and it was soon clear the airman was bleeding to death. A German bullet had severed most of Pat’s leg.

Back To Service

There was nothing much Yeager could do but take a pen knife and sever the remaining tendon, completing the amputation. After staunching the bleeding, he then carried his companion through miles of snow-covered ground. Yeager refused to abandon Pat, only doing so when he was convinced the wounded man was dead. Later, Yeager discovered that Pat had been found by the Spanish Guarda Civil, weak but alive. Pat eventually was sent home and survived the war.

Now alone, Yeager stumbled on. He reached Spain and turned himself into the police in a small village. Yeager was allowed to check into a local hotel, and before long the nearest American consul showed up at his door. The American pilot was technically interned, but in reality it was a six-week wait in an Alma de Aragon resort hotel. All expenses were paid by the U.S. government.

Yeager seems to have enjoyed himself, soaking up the sun, eating (he gained 20 pounds), and flirting with pretty chambermaids. While the pilot lived a life of relative luxury, U.S. authorities negotiated with the Spanish government for his release. Eventually, a deal with struck. Six evader airmen, including Yeager, would be released in exchange for gasoline.

Now officially free, Yeager looked forward to going back home and marrying his sweetheart Glennis. He returned to England to pick up his things before going on to the States, but while there he experienced a change of heart. Officially, anyone who managed to evade capture was out of the war. It was reasoned that if he returned to combat, he might get captured again.

If recaptured, an airman might be tortured to reveal the names of those who helped him, or even the locations where the Maquis liked to hide. Yeager understood this, but the idea of “running away” while his buddies fought on was a notion too painful to bear. He was, by his own admission, a “stubborn cuss.”

Yeager decided he was going to stay, come hell or high water, and was willing to go right up the chain of command if necessary. It was necessary. On the whole, the brass gave him a sympathetic ear because he was the first fighter pilot evader to actually it make to back to base. In fact, Yeager managed to secure an interview with General Dwight D Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force just then gearing up for the invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

Promoted to Lieutenant

After surviving air combat, being shot down, and even enemy bullets on the ground, ironically Yeager almost fell victim to a German V-1 attack on London. He was in his hotel room preparing to see Eisenhower when he heard what he later described as a put-put-put that sounded like a jet engine. It was a V-1 flying bomb, one of the infamous buzz bombs or “doodlebugs” that the Germans launched on the British capital in 1944.

Yeager took a look out the window just in time to see the V-1’s engine cut out and the bomb itself plunge to earth from an altitude of about 1,500 feet. The pilot hit the deck of his hotel room just as the V-1 exploded a few blocks away. The meeting with the supreme commander went on as scheduled.

General Eisenhower was sympathetic, and in the end Yeager was allowed to stay. By the time the decision was made, the Allies had already invaded France, obviating the need to protect the Maquis. His fighter group was happy to see him, though he was kidded about his escape: “Yeager, when are you going to do things right? When you are shot down, you are supposed to stay down!”

The period from summer 1944 to winter 1945 was the peak of Chuck Yeager’s World War II career. He was finally promoted to lieutenant and ended the war as a captain. He excelled in the dogfight, a man-to-man, plane-to-plane duel in which skill was just as important as courage. It was during this period that he flew the P-51D-20NA, which he named Glamorous Glenn after his stateside intended.

Yeager Becomes an Ace

Yeager became an ace in a day on October 12, 1944, though the first two credited kills were unique. Yeager bagged them without firing a shot. As he was closing in on one Me-109, the German banked sharply and ran into his wingman. Both pilots bailed out, giving Yeager credit for two Messerschmitts. The other three kills were earned the old fashioned way—skill, daring, and a little luck.

Yeager became an ace in a day on October 12, 1944, though the first two credited kills were unique. Yeager bagged them without firing a shot. As he was closing in on one Me-109, the German banked sharply and ran into his wingman. Both pilots bailed out, giving Yeager credit for two Messerschmitts. The other three kills were earned the old fashioned way—skill, daring, and a little luck.

In the fall of 1944, the German Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter went into service, albeit in relatively small numbers. Nazi policy seemed to focus on the Allied bombers, so fighter pilots like Yeager rarely encountered one. When they did, the jets were so fast they could easily outdistance any attacker. But Yeager got lucky when he caught an Me-262 in the process of landing and shot it up. This was not as “romantic” as a one-on-one duel, but did have real hazards. As he pounced on the jet, German antiaircraft units guarding the field peppered the sky with flak.

Strafing targets was a distasteful duty, but often necessary. German or French civilians might be in the way, but mission strategy trumped conventional morality. The object of war is to win, and in World War II the dividing line between combatant and innocent civilian was sometimes blurred. If a target was near a farmhouse or a hotel, civilians might be killed. Though he would do what was necessary, Yeager preferred the straightforward challenges of dogfighting.

There was some glamour attached to being a fighter pilot, but Yeager willingly admits that it was not all fun and gallantry. On a typical mission he would take off at 8 am. Before going aloft there would be many things to take care of like properly suiting up and being attentive in a morning briefing.

His Test Pilot Career Still Ahead of Him

But even the small things like going to the toilet assumed a certain importance. Yeager, earthy but honest, has said you had to “pee” before leaving the ground. The elimination tube would usually be frozen solid, and a pilot knew he would be in the cockpit for at least six hours, maybe more. Much of the time he would be at 30,000 feet, and despite a small heater his body would be “frozen” from the waist down. At least his head and upper torso might catch a few warming rays from the sun.

The cabin in the cockpit was not pressurized, so a P-51 pilot would have to clip on his oxygen mask. Even so, at 30,000 feet a man might get easily fatigued. By the time he got back from a mission he was stiff, sore, and utterly exhausted. And yet through it all Yeager loved the life of a fighter pilot. There is no question most of the others loved it as well.

Captain Yeager flew his last combat mission on January 15, 1945. It was a clear and beautiful day, unusual for wintertime Europe, and he was flying with his close friend Clarence E “Bud” Anderson, a great fighter pilot in his own right. He was ordered back home, returning to the States in February 1945. He had flown 64 combat missions, some 270 hours. He was credited with 121/2 kills.

Chuck Yeager went on to achieve great fame as a test pilot. And yet he should also be remembered for his outstanding record in World War II. As he once put it, “I don’t deny I was damned good. If there is such a thing as ‘the best,’ I was at least one of the contenders.” Yeager passed away on December 7, 2020 at age 97.

I love your article, thanks a lot for good reading. You have only one mistake there, Chuck was credited with 11,5 kills during the WW2.

Great read about one of my heroes.

Probably the best fighter pilot in history.

Yaeger was great guy and a genuine ace, and this was a genuinely informative and interesting article. But he was definitely not the best fighter pilot in history, probably not even the best American fighter pilot in history.

Respectfully, I disagree with Mr. Phelim. Gen. Yeager was simply the best fighter pilot of WWII, hands down.

A great read what a life

Until I read “Yeager, an autobiography” I thought his only claim to fame was being the first to break the sound barrier. This guy achieved so much more before and after Oct. 14th, 1947.

I am wondering if this Chuck Jaeger is the same person who flew an aircraft around the world without refueling. His aircraft was nicknamed “The flying gasoline tank.”

hard to read on the internet so I get the magezine.

Thanks for this part of his story. I wish they would make a film or TV show about his complete life. Hopefully it’s respectful.

I have Chuck Yeager’s book. It’s been a while since I’ve read it but some of the stuff in this article doesn’t jive. FYI, I was friends with him on Facebook and we corresponded. He told me the P-51 was so vulnerable “you can bring one down with a slingshot.” His words.

You are correct, Sam. The P-51 was liquid-cooled and ground fire, from even a well-placed rifle shot, could penetrate the radiator causing a loss of coolant which would cause the engine to quickly overheat. I read his autobiography also and, as I recall, he retired a brigadier general although many, especially his wife, felt he deserved another star. I agree wholeheartedly!

He lived to 97 passing away on the 79th anniversary of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbour… incredible