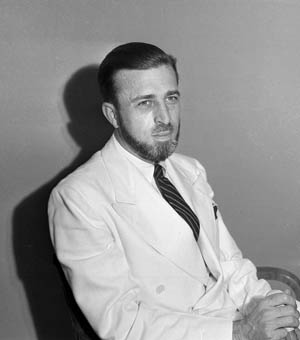

By John W. Osborn, Jr.

It was the most exciting scene Associated Press correspondent Robert St. John had yet witnessed in the career he had abandoned for five years to farm in New Hampshire then returned to when he sensed that war was coming.

It was March 27, 1941, and Terrazia, the Times Square of Belgrade, capital of what was then Yugoslavia, was packed with crowds jubilant at their country’s sudden stunning, defiance of Adolf Hitler. The mood quickly turned to anger, though, directed at St. John when he began to get down to his job of reporting.

“If I wanted to photograph these scenes I must be a Nazi agent gathering evidence, trying to get onto film the faces of those responsible, so they could be punished in true Nazi style when and if Hitler got this country under his thumb again,” he recalled. “That was the way they seemed to figure it.”

Early in his journalism career in notorious Cicero, Illinois, the town owned by Al Capone, St. John had been set upon by thugs and left for dead in a ditch. Understandably anxious to avoid a repetition, he waved his passport and a small American flag; the fickle crowd turned to ransacking the tourist agency of Hitler’s ally Italy while he took the opportunity to hotfoot it from the square.

Just 10 days later St. John would be back in Terrazia Square to witness a very different, tragic scene before running again—this time right out of the country before one of World War II’s briefest but most brutal blitzkriegs, the effects of which would be felt to the end of the 20th century. Yet another American, a female member of a distinguished political-military family, would also be on the run—not from danger but deliberately heading straight into it with near fatal results.

Yugoslavia was the makeshift attempt after World War I to bring the lands and people of the southeastern Balkans, formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian empire of the Hapsburgs, under the rule of the royal house of Serbia. But, it turned out, union did not mean unity. Almost a dozen nationalities and ethnic groups seethed with resentment, none more so than the largest among them, the Croats.

The political powder keg finally exploded in 1929 when a member of a different national group gunned down three Croatian deputies during a riotous session of Parliament. Arguing he needed to act to prevent civil war and secession, Serbian King Alexander I moved swiftly to establish a dictatorship.

The response by Croatian extremists out for independence was to found a terrorist group, the Ustachi, which engineered the king’s assassination in France in October 1934.

With his heir Peter II just 11, a cousin, Prince Paul, assumed a regency. The result was power without leadership. The prince, a cultured figure with little interest in or much aptitude for politics, made no secret he was just marking time until he could hand responsibility to the king on his 18th birthday in September, 1941.

Unhappily for the prince and tragically for Yugoslavia, Adolf Hitler would not wait. Preparing for his invasion of Greece, Hitler put relentless pressure on the nations of the Balkans to sign his de facto alliance, the Tri-Partite Pact. Robert St. John found himself rushing from capital to capital: “Weeks of ‘Will they? Won’t they?’ Weeks of dope stories based on the slimmest of chancellery gossip. Weeks of writing two or three long dispatches a day trying to keep the story alive while we waited for the inevitable to happen.”

Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania fell into line, and St. John found himself waiting in Belgrade for Yugoslavia’s turn to fold. Also observing events anxiously there was the other American, the woman of distinguished family, determined to do more about events than merely report on them.

Ruth Mitchell was the daughter of a one-time United States Senator from Wisconsin and the sister of General Billy Mitchell. A journalist herself, she accepted the fateful assignment of covering the comic-opera wedding of Albania’s outlandish King Zog I in 1938. “If I had known then what was coming,” she would reflect after the end of her ordeal, “would I have turned back? The answer is a completely certain No!”

Intending to stay just a few days for her story, she instead became so intrigued by Albania that she gave up her career to stay and study it. Driven out by the Italian invasion in early 1939, she then moved to Yugoslavia. There she became enthralled by Serbian history and culture. “The Serbs,” she was to write, “are a very small race; there were before the war not more than eight million of them. But it is a race of strikingly individual character, of extraordinary tenacity of purpose and ideal. That ideal can be expressed in a single word: Freedom.”

With the same uncompromising intensity for a cause and personal flamboyance that had cost brother Billy his military career due to his vocal advocacy of military aviation in the United States, she went so far as to enlist in the legendary Serbian Chetnik militia, complete with fur hat, skull and crossbones emblem, uniform, boots, dagger, and poison pill in case of capture.

“The soul of Serbia on the march! I was a Chetnik—until death,” she exulted.

For his part, though, Robert St. John was skeptical. “It seemed to me that Miss Mitchell was just looking for some Hollywood adventure. Well, I thought, she’ll probably get all she wants before long.”

Foreign Minister Aleksander Cincar-Markovic, then Prime Minister Dragisa Cvetkovic, and finally Prince Paul himself got the feared summons to meet Hitler at Berchtesgaden. “Fear reigned,” Churchill would record. “The Ministers and the leading politicians did not dare to speak their minds. There was one exception. An Air Force general named Simovic represented the nationalist elements among the officer corps of the armed forces. Since December his office had become a clandestine center of opposition to German penetration into the Balkans and to the inertia of the Yugoslav government.”

Serbian public opinion, remembering their support during World War I and afterward for independence, was overwhelmingly pro-British. “I am out of my head!” Prince Paul bewailed under the strain. After a second visit to Hitler and the assurance—for what it was worth— that all that was wanted was his signature, the prince finally sent Prime Minister Cvetkovic and Foreign Minister Cincar-Markovic to sign the Tri-Partite Pact in Vienna on March 25, 1941. To the protesting minister from the United States, Prince Paul replied bitterly, “You big nations are hard. You talk of honor, but you are far away.”

Ruth Mitchell’s Serbian friends visited, anguished and humiliated at what they considered the betrayal of a friend. “We had written our capitulation stories, packed our bags, and argued over where the next crisis was likely to break out,” St. John later wrote. “But then something happened that forced us to unlimber our typewriters, dig copy paper out of our suitcases, and get to work in Belgrade again.”

Prince Paul had warned Hitler that if he signed the pact he would not last another six months in power. He would be off in his calculations by five months and 28 days.

The day after the signing, demonstrations, started by students, erupted on the streets of Belgrade. As he watched, a secret policeman next to St. John remarked, “You newspaper boys better keep your pencils sharp. Things are going to happen in Yugoslavia yet!”

At 2:30 the next morning, St. John was awakened by a phone call from a colleague who informed him that troops and tanks were in the streets. Rushing out, he was soon led under guard to a park to join prostitutes, cleaning women, and other night-crawlers.

“We were watching the unfolding of a first class, full-dress coup d’etat,” he recognized.

Without a shot, government buildings were occupied and ministers arrested at their homes. At the palace, the guards opened the gates to the rebels without resistance while young King Peter II climbed down a drainpipe to join them. Soon, General Simovic, the leader of the revolt, arrived to announce, “Your Majesty, I salute you as King of Yugoslavia. From this moment you will exercise your full sovereign power.”

Prince Paul had been heading to his country estate for a badly needed rest. He would get a longer one. His train was intercepted and rerouted back to Belgrade. Under guard, he was then trooped into the office of the new prime minister, General Simovic, to sign his resignation. He finally reboarded his train with many of his ministers for a new destination, Greece. They were luckier than they knew. Ruth Mitchell had been tipped that the Chetniks were launching their own coup, which intended to leave none of them alive. Foreign Minister Cincar-Markovic was one the few kept on in the new regime, with a personally tragic consequence.

“Few revolutions have gone more smoothly,” Churchill would comment. The king, who had just learned to drive, without guards creeped and beeped his way through the packed, wild, streets.

The euphoria soon wore off as the grim reality of their position began to set in on the Serbs. Just three days after the coup, the new government timidly announced it would abide by the Tri-Partite Pact after all.

It was already too late. Hitler had reacted to the news of the coup with an awesome, eardrum-bursting blast of blind fury, then issued Directive 25 not merely to invade but to completely destroy Yugoslavia. “The tornado is going to burst upon Yugoslavia with breathtaking suddenness,” he vowed.

At the main planning session with high-ranking henchmen, Hitler made another statement that was to doom a country. The officer taking down the minutes felt compelled to underline it: “The beginning of Operation Barbarossa will have to be postponed up to four weeks.”

“Belgrade those last two days of peace was a weird place,” Robert St. John would remember. “A heavy, depressing atmosphere hung over the city.” He went to the train station to see the German legation depart but noticed the military attaché was not there. One of the officials made a remark that left him pondering the meaning. “We’ll be back soon. Probably very soon. And when we come we’ll bring a few souvenirs for you boys.”

St. John would not be there to see them when they returned. He was ordered to report the next day, Palm Sunday, April 6, 1941, at 3 pm for an immediate expulsion order. Back in his hotel for his last night in Yugoslavia, he got a new head scratcher, a call from the Associated Press office in Berlin cryptically suggesting he not go to bed. “We think up here it would be an excellent night for you [to be] listening to the music from the Berlin broadcasting station.”

St. John dutifully kept vigil all night. Finally, at 4 am German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop suddenly came on the air. St. John could not make out what he was shouting about, but Ruth Mitchell, at home, did. “The bombs fall and already now this instant Belgrade is in flames.”

St. John phoned a Yugoslav colleague. “War! War! War is here, St. John,” the Yugoslav responded.

With another American reporter, St. John rushed to the balcony of his hotel room. “We heard the planes before we saw them,” he would later describe. “At first it was just a faint drone. Like a swarm of bees a long way off. Then louder, louder! LOUDER!”

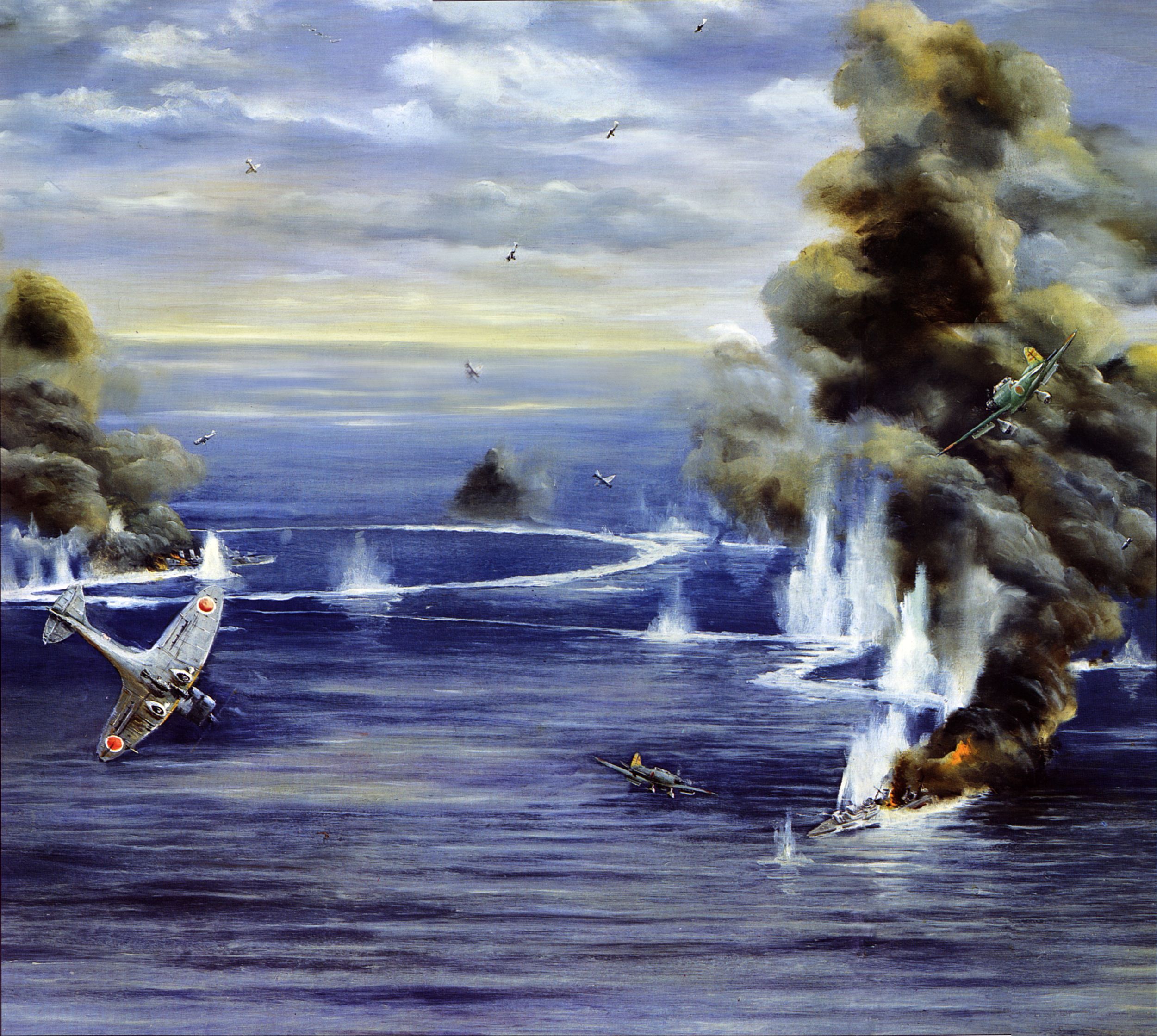

The Yugoslav military attaché in Berlin learned of the sledgehammer blow about to fall but had been, foolishly and fatally, disbelieved in Belgrade. Now more than 300 Luftwaffe aircraft—dive bombers, medium bombers, fighters— were heading in to commence one of the war’s worst terror bombings, codenamed bluntly and brutally Operation Punishment.

St. John and his colleague quickly tore down the stairs as explosions shook the hotel to wait it out in the crowded, panic-filled lobby. At home, Ruth Mitchell was sheltering under the stairwell while bombs were falling scarcely 20 yards away. “The effect was almost inconceivable,” she would write. “It wasn’t the noise or even so much the concussion. It was the perfectly appalling wind that was most terrifying. It drove like something solid through the house: every door that was latched simply burst off its hinges, every pane of glass flew into splinters, the curtains stood straight out into the room and fell back into ribbons.”

The only Yugoslav aircraft to get airborne were, ironically, Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters supplied earlier by Germany. Those not brought down by the far more experienced Luftwaffe sometimes were by mistaken antiaircraft fire from the ground. The Luftwaffe struck around the clock in waves every two to four hours. St. John used one lull to pick his way through the rubble for the U.S. Legation.

He passed a truck stacked with dead, the ramp down with legs sticking out. He went through Terrazia Square, scene of the celebrations he had witnessed then had run from just 10 days before. “Pieces of peoples’ bodies,” he saw. “Jewelry and groceries and clothing out of shop windows. Glass and stone. Chunks of bombs and jagged pieces of tin roofing.”

St. John was certain the Germans had dive bombed the square in revenge for the celebrations there. One body riveted his attention, that of a young woman in an evening dress. “I looked down on her,” he recalled, “and wondered where she had been last night, to still have on an evening dress at five o’clock in the morning. Then I noticed her right leg. Half of it was gone. Sawdust trickled out of the stump. My lovely brunette had been blown out of a shop window.”

St. John finally reached the Legation followed soon after by Ruth Mitchell in her Chetnik uniform. “Where’s your horse? I asked her,” St. John later wrote. “She didn’t laugh.”

She had good reason. Along her own way through the devastation she had come upon a scene “which will haunt me while I live—a gaping hole where an air raid shelter had been and in the trees around legs and arms, many of them so pathetically, tragically, small, dangling from the branches.”

At the time he was to have been expelled, St. John was driving out of Belgrade during another air raid. At his side was a young Serbian girl who asked for his help and proved invaluable in hunting for food and lodging in the days ahead. King Peter was again at the wheel amid the motorized mob. He would never see his capital again.

“The vehicles on that road leading out of Belgrade were a strange sight,” St. John later recorded. “There was everything in the parade that man had ever invented to run on wheels, from the crudest kind of oxcart you ever saw, up to some diplomatic limousines fancy enough for an Indian Maharajah …

“The people we felt really sorry for were those who had everything they owned tied in bundles on the end of sticks they carried over their shoulders. Instead of following the winding highway, these footloose people trudged across the fields because that way was shorter, even though they did have to struggle down through little valleys and then up steep hills. That ribbon of people is still one of the most vivid pictures of the whole war.”

The absence of panic made St. John wonder if Americans would react the same way. He doubted it. “The difference, I suppose,” he reflected, “is that those poor Europeans, and especially people like the Serbs, are so used to war and destruction that they have got resignation in their bones. They just take it. There isn’t much else they can do.”

Ten miles out of the city St. John stopped on a hilltop for a final look. “We could see Belgrade,” he recalled. “Burning Belgrade. Belgrade already well on the way to becoming a city of silent people. Except that a lot of these men and women lying around in the streets were probably still moaning for help and a drink and something to stop the pain.

“We could see the smoke from dozens of fires. And up through the smoke the red flames. It looked as if there was another air raid going on. We were too far away to hear sounds distinctly, but what we did hear was a dull noise that was probably a brew of all the miseries of war mixed together. The noises of planes and guns and sirens and falling buildings.

“But what made us think the raid was going on in earnest again were the little dark dots in the sky and the puffs of white smoke, which we knew came from the shrapnel set up by the ack-ack guns as they tried so hard and generally so futilely to pin one on the bombers.”

In the late afternoon the Germans had been dropping incendiaries to light up the city for the night attacks. Ruth Mitchell had been among those fleeing on foot and from a village had the same, grim, view as St. John. “The great city on the Danube seemed to be one blazing bonfire. Great tongues of fire would burst suddenly, glare fiercely for a while and slowly sink away. Suddenly heavy clouds of smoke coiled upwards, billowing, writhing, twisting into the sky, reflecting on their black bellies the angry glare that must have been visible for hundreds of miles across the huge river and the limitless flat plain.”

When the air assault and slaughter ended after two horrific days, the city of Belgrade was in ruins and an estimated 17,000 were dead. Robert St. John, who had just come for a story, quickly decided it was hopeless to continue reporting so he had to get out of Yugoslavia.

Ruth Mitchell, who had found a cause, elected to stay. “I was full to the brim and running over with fury,” were her feelings. “I swore to myself that while there was breath in my body I would fight to save what those monsters of cruelty would leave of a people whose dream they could never understand.” But her personal crusade was to end before it could get started—and her real ordeal would begin.

Less than an hour after the bombing of Belgrade had commenced, the ground invasion got underway. “It is vital for the blow to fall on Yugoslavia without mercy. There must never again be a Yugoslavia,” Hitler had decreed. Yugoslavia’s neighbors had been bullied under the Tri-Partite Pact to join in or permit passage of German troops. Hungary’s foreign minister, who not long before signed a friendship treaty with Belgrade, alone made an honorable, if futile, protest—he shot himself.

The invasion had been so hastily ordered that some Wehrmacht units were still en route from as far as Germany, or just getting orders. Fully eight divisions would not get there in time, but those that were there proved enough to overwhelm the hapless Yugoslavs.

The German Twelfth Army and 1st Panzer Group attacked from Bulgaria, the German Second Army and Hungarian 3rd Army from Austria, Hungary, and Romania, and finally the Italian 2nd Army from occupied Albania. To meet the multisided onslaught, the Yugoslav Army had almost a million men. It was an army, though, with antiquated weapons, a transport system based on the sluggish oxcart (a Yugoslavian unit required a whole day to cover the distance an equally sized but motorized German one could speed across in an hour), and a defense plan stubbornly based on holding the entire 1,900-mile border instead of withdrawing to more defensible positions as the British had urged.

And just how weak these border defenses turned out to be was glaringly exposed as a German bicycle company jumped the gun and pedaled more than 10 miles before having to fire a shot! However, the greatest weakness of all for the Yugoslavian Army was its other, equally deadly, enemy—the one from within.

“It is a sad fact,” Ruth Mitchell was to bitterly comment, “that Yugoslavia, of all the small nations of Europe, is the only one in which a large portion of her army with its regular officers turned traitor to their oaths.” That portion she was referring to was the Croats, who saw the invasion as an opportunity to throw off Serbian rule and eagerly took with a long-simmering vengeance.

One Croatian officer had defected to the Germans three days before the invasion with Yugoslavia’s air defense plans, enabling the Germans to pinpoint targets, particularly government buildings, in bombing Belgrade, then to locate local airfields to catch and destroy the obsolete Yugoslav air force on the ground. More than 1,600 others, 95 percent of the Croatian officers in the army, also deserted to the Germans while Serbian officers by the hundreds were murdered by their Croatian troops.

Equipment was disabled, communications disrupted, transport diverted. Croatian soldiers would wave on or outright cheer passing German formations. One was notoriously filmed handing over his rifle and, with a stupid grin on his face, offering to shake hands as the German smashed the weapon on the ground and, with obvious disdain, walked away.

From her train window Ruth Mitchell watched Croatians celebrating, with the royal Yugoslav flag hung with contempt upside down. The train repeatedly came under fire from mutineers. “Suddenly a sharp burst of firing. The train jerked to a stop. Our soldiers, yelling raucous curses at the Croats, tramped down the corridor, jumped out and down the embankment. Violent firing continued for 10 or 15 minutes. I could watch the flashes of the guns as our Serbs hunted the traitors among the trees and shrubs along the embankment.”

She got a further glimpse of the hopelessness of Yugoslavia’s position when she met on the train a Montenegrin peasant, gaunt, clothes in tatters, rags around his feet instead of shoes, who told her how he had rushed off from home to fight armed with just a knife. “There were only big iron monsters—tanks in long rows coming down on us. And what use—what use are knives against tanks?” he kept repeating.

The terrain at times was a more stubborn adversary. German armor so rutted the dirt roads that oxen were seized from the Yugoslavs to pull supply vehicles. Skopje fell to the German Twelfth Army on the second day, sealing off the border with Greece. When the news hit Sarajevo, which he had reached, St. John knew what that meant. “Poor Yugoslavia was hemmed in on three sides. The necklace of steel was tightening…. And it meant that all those thousands of people in Sarajevo had only one way out now. The Adriatic!”

Good Friday in Sarajevo was anything but as the city was repeatedly bombed—St. John sadly watching soldiers shoot at the aircraft, then dance around thinking they had driven them off—and diamonds were being offered for gasoline. “It was a battle of wits, with no tricks barred,” St. John would say about the relentless hunting for gas. “Whenever we parked the Chevrolet anywhere, one of us had to stand guard to make sure some unscrupulous or hysterical refugee wouldn’t break the lock on the gas tank and siphon out our last drop of fuel.”

With panic full on, the scenes in Sarajevo’s cafes reminded him “of the New York Stock Exchange on a two-million trading day.” Luckily, St. John remembered an army depot outside of town; the officer in charge, resigned to the Germans coming, let him have all the gasoline he needed.

With the Yugoslav command structure destroyed by design in the bombing of Belgrade and the king and government on the run, Yugoslav forces in the field were leaderless. On his flight for the coast St.John met general staff officers who took their time dining and chatting with him. “Members of the Yugoslav General Staff, on the eve of a great military debacle, were spreading butter on salted biscuits and talking about things that didn’t matter and never had mattered and never would matter,” he would recall with dismay.

The Germans often simply bypassed what pockets of resistance there were. One Yugoslav unit made a desperate nighttime charge out of the woods against a village Germans were billeted in. Grabbing their boots, helmets, and weapons, the Germans, still in their underwear, soon drove off the attackers.

Racing 100 miles a day, the German Second Army rolled into the Croatian capital, Zagreb, on April 11, to be cheered for the first time in the war by a non-German population. The Ustachi declared independence and set up the most crazed, murderous, quisling regime of the war. “In the north of Yugoslavia the front is breaking up with increasing rapidity,” General Franz Halder of the German General Staff, who knew what they were doing, recorded in his diary. “Units are laying down their arms or taking the road to captivity. One cycle company captures a whole [unit] with its staff. An enemy divisional commander radios his superior officer that his men are throwing down their arms and going home.”

The German Twelfth Army had broken through a strong defense line of bunkers and antitank batteries then driven northwest 213 miles through the Morava Valley in seven days toward Belgrade. Other Wehrmacht units were closing in from the southeast, through Serbia where resistance had been the stiffest, and from the west, but all were beaten to the prize by a tiny unit of the hated rival, the Waffen SS.

A motorcycle assault company of the SS Das Reich Divison led by Captain Fritz Klingenberg and attached to the German Second Army reached the opposite, north bank of the Danube on the morning of April 12, 1941. Though the river was flooded, Klingenberg located a motorboat and with a lieutenant, a pair of sergeants, and five privates grandly set off to conquer a capital.

They were nearly swamped, but crossed successfully. On shore they surprised a score of Yugoslav soldiers who, at the sight of them, just dropped their weapons and threw up their hands. When Yugoslav military vehicles arrived shortly afterward, Klingenberg fired on them, boarded, and then headed into the ruined city.

With no one to stop him, he made his way to the wreck that had been the Ministry of War, then drove on, weaving through the rubble, to the German Legation. It was untouched. The Luftwaffe had spared the blocks around it.

The military attaché, Robert St. John noticed, had not left, and Klingenberg ran up the Swastika at 5 pm to proclaim Belgrade’s fall. The mayor appeared two hours later with what little authority he had left to make it official, and the next morning German armor crunched the debris to make it final.

The last major city left, Sarajevo, fell two days later. Cruelly fitting, the Yugoslav government official who surrendered the country had signed Yugoslavia’s first capitulation to Hitler in Vienna just a month before—Foreign Minister Aleksander Cincar-Markovich.

King Peter and Prime Minister Simovic had flown out from one of the few remaining operational airstrips incongruously aboard another German aircraft purchased during better days with Berlin, a Junkers Ju-88. Along the way they ran short on fuel and had to put down at a makeshift British airfield in Greece, with airmen rushing it with pistols in hand.

“And I’m Father Christmas!” an irate British pilot responded when the young king identified himself. “Now come on, get out.”

After the king convinced the British of his identity, Simovic passed out on gin and had to be carried back on board for the flight to Athens. Aboard British aircraft now, this was the beginning for King Peter II of a long, sad road leading to Jerusalem, Cairo, London—and ending on a barstool in Los Angeles.

Robert St. John would make his own perilous escape from Yugoslavia. On a winding mountain road he passed troops building tank traps and reflected on the futility. More hopefully, he saw others, rifles on their shoulders, heading up into the forests to launch what became one of World War II’s epic guerrilla resistance movements.

He delivered his Serbian companion to her family, and his last memory of Yugoslavia was the sight of her in his rear view mirror waving proudly. At the coast he and three other journalists boarded a 24-foot sardine boat to sail down along the coast for Greece.

The only one with any experience at sea, however, was St. John, who had swabbed the deck of a Navy transport during World War I. The voyage soon turned into a desperate struggle against pelting rain and stiff wind, requiring bobbing and constantly bailing.

“Several times the combined force of the wind and waves tore the oars from our hands, and we had to risk drowning to grab them as they flew through the air and landed on the water,” St. John would be lucky to write later. The most dangerous moment came when an Italian warship spotted them and trained its guns. St. John and the others held up an American flag and, after several tense minutes, they were waved on.

After four days they reached the island of Corfu on April 20, 1941. From there St. John reached the Greek mainland only to be caught up in the German blitzkrieg there. After surviving more bombings he squeezed aboard what turned out to be the last British evacuation ship. From there it passed through Crete just before the German invasion, then went on to Alexandria, Cairo, Cape Town, and finally reached New York.

Back home he was advised to go easy on his remarks at an after-dinner lecture and rest in the country to forget and find perspective. “I didn’t make pleasant remarks in that lecture,” he concluded in his account of his experiences in Yugoslavia and Greece, From the Land of Silent People (1942).

“I didn’t go to the country to try to forget. Maybe I don’t have any perspective,” he wrote.

Ruth Mitchell also made her way to the coast, reaching Dubrovnik. Along the way she met British diplomats who offered to evacuate her. “I did think about it all that night…. But, of course, my choice had been made a long time ago, when I became a Chetnik,” she was, like St. John, fortunate to write later.

Italian forces arrived, and she gamely mapped their positions while preparing to rejoin the Chetniks. But the day before she was set to flee, on May 22, 1941, she was arrested by the Gestapo. Sentenced to death as a spy she was imprisoned in Belgrade, then in Germany. In the end she would sail from Lisbon aboard the last shipload of repatriated Americans, to reach New York on June 30, 1942, and later tell of her own eventual time in The Serbs Choose War (1943).

Ruth Mitchell proved luckier than the 6,028 officers and 337,684 soldiers of the Yugoslavian Army who also went, but stayed, in captivity. The poisonous ethnic hatreds that doomed Yugoslavia to swift, ignominious defeat and the decades of suffering that lay ahead were reflected in how fewer than two percent of those prisoners were Croats who refused the Nazis’ offer of release.

The last Yugoslavian casualty of the invasion did not die until 1970. He was the sad, boozebloated shell of the trim young man who, for a brief moment, had been the hope and idol of at least part of his country, King Peter II.

Driven out by Hitler then kept out by Tito, he could never adjust to exile or abandon the fantasy of one day returning to his throne. Fed up with his maudlin self-pity, his wife, a Greek princess, finally gave up on him and left. He ended his days in Los Angeles, destitute, despondent, drinking (the author’s late father, a used car dealer in Long Beach, had a repossessor working for him who knew the king in LA’s dingier establishments). When liver failure finally put him out of his misery at just 47, the King–for-ten-days made a final bit of royal history. He was the only king ever to die in the United States.

To borrow from Churchill, Yugoslavia’s swift surrender proved only the end of the beginning for what lay ahead. As brutal as they were, the German and Italian occupations paled in comparison to the reign of terror the Ustachi in Croatia launched against Serbs, Jews, and Gypsies. When the Communists defeated the Chetniks and took over, a Croat would finally be leader of all of Yugoslavia, but Tito’s rule proved more iron fisted, not least against his own people, than any Serb king could have imagined.

When Communism and the Cold War ended, so did Yugoslavia finally. The breakup, though, soon turned into a nightmare of war, ethnic cleansing, wholesale massacre, and systematic rape culminating in the 1999 NATO bombing campaign.

It would not be until 2000, when the Serbian strongman at the bottom of the turmoil, Slobodan Milosevic, was voted from office by his war-weary people and died in United Nations custody while being tried as a war criminal, did the ordeal that started that Palm Sunday finally come to an end. Ironically, separated, the parts of what became generically referred to as the former Yugoslavia became what they could never be as a whole—prosperous and democratic.

Ironically, in his furious determination to obliterate Yugoslavia, Hitler very likely brought about his own self-destruction. The cost of the invasion did, at the moment, seem cheap—151 dead, 392 wounded, 15 missing, but, as the well-known chronicler of the Third Reich’s rise and fall, William L. Shirer, noted, the real price was paid later. “The postponement of the attack on Russia in order that the Nazi warlord might vent his personal spite against a small Balkan country which had dared to defy him was probably the most single catastrophic decision in Hitler’s career.

“It is hardly saying too much to say that in making it that March afternoon in the Chancellery in Berlin during a moment of convulsive rage he tossed away his golden opportunity to win the war and to make the Third Reich, which he had created with such stunning if barbarous genius, the greatest empire in German history and himself the master of Europe.

“Field Marshal von Brauchitsch, the Commander of the German Army, and General Halder, the gifted Chief of the General Staff, were to recall it with deep bitterness but also with more understanding of the consequences than they showed at the moment of its making, when later the deep snow and subzero temperatures of Russia hit them three or four weeks short of what they thought they needed for final victory. Forever afterward they and their fellow generals would blame that hasty, ill-advised decision of a vain and infuriated man for all the disasters that ensued.”

Author John W. Osborn, Jr. is a resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has previously written for WWII History on numerous topics such as the British Long Range Desert Group and Polish General Wladislaw Anders.

The communists haven’t had defeated the Chetniks. In reality, 1 million Soviet army and their neighboring affiliates entered Serbia from east, hunted the Chetniks (who already freed most of Serbia from Nazis until autumn 1944) and installed tito in Belgrade forcing Mihailovich’s Chetniks to withdraw in eastern Bosnia until the Soviets leave into Austria towards Berlin. The author might be interested to read our books which gives new findings (especially “WW2 in the Balkans: the Actual History – Yugoslav real resistance”), available on our website or here

https://www.fnac.com/e367271/Pogledi-Editions