By Jonathan North

On Monday, February 19, 1476 Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (much of what is now eastern France), joined his army beneath the gray ramparts of Grandson. His troops, disheartened by an unsuccessful assault the day before, now hailed him with cries of “Burgundy! Burgundy!” while the five hundred Swiss defenders, besieged in the town, looked down from their walls on the magnificent scene below.

Early the next morning, the Burgundian artillery opened up anew and, despite a breach not yet being ready, preparations were made for a fresh attack. The assault, launched on the 21st, succeeded in chasing the Swiss into the citadel, an imposing and impregnable place looming over the town and neighboring lake. Charles redeployed his artillery, although he was without his heavier siege pieces, still trundling up over the Jura mountains, and began the task of finally reducing the place to submission.

The weather was wet and raw, and the Burgundian army, long accustomed to war and consisting of troops from all over Europe, dispersed across the neighboring villages to find shelter. As the siege tightened, Charles heard rumors, then reports, of the Swiss cantons gathering a relief army; he issued stern orders for his troops to return to the Burgundian camp and braced himself for the impending confrontation.

Charles the Bold was a powerful figure and ruler of territory including all of present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, Picardy (northeast France), Burgundy, Franche-Comte (both now in eastern France) and Luxembourg. He was a mortal enemy of King Louis XI of France, who was trying to consolidate and expand his own territories. In 1475 Charles overran Lorraine, chasing out its duke and effectively linking his southern territories with his northern ones.

Charles the Bold was a powerful figure and ruler of territory including all of present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, Picardy (northeast France), Burgundy, Franche-Comte (both now in eastern France) and Luxembourg. He was a mortal enemy of King Louis XI of France, who was trying to consolidate and expand his own territories. In 1475 Charles overran Lorraine, chasing out its duke and effectively linking his southern territories with his northern ones.

There was a price—Charles had been at war constantly for the past two years—but the effect of this coup sent shudders throughout Europe. Most alarmed of all, despite his practical nature, was Louis XI of France. Louis found the Swiss to be receptive to his offers of alliance, and his promises of cash, particularly the city-state of Berne.

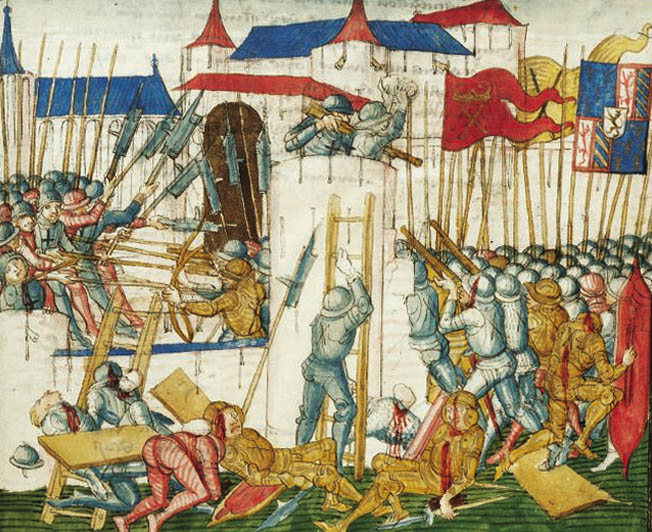

Berne itself was in an expansionist mood and in the spring of 1475 had raided the Pays de Vaud and Jura, looting, destroying, burning and defeating the small and poorly organized forces the petty counts and lords of the region could raise. The expedition was characterized by wanton savagery more fitting to the Dark Ages than to Renaissance Europe. Villages were burned and towns sacked. A typical incident was the storming of Jougne, a regional center; houses were set afire, inhabitants pillaged or butchered and the garrison of three hundred was taken up to the ramparts and thrown down onto the rocks below.

In the autumn of 1475, just as Charles was overrunning Lorraine, the men of Berne mounted a more ambitious expedition. Morat fell to the Swiss under the redoubtable Scharnachtal, quickly followed by Estavayer. This latter stronghold was stormed and the garrison slaughtered. Those that surrendered were thrown from the battlements or tied together and drowned in the lake. Geneva was then threatened and forced to buy the Swiss off, then Lausanne. Territory belonging to Savoy was ravaged and the Regent, Charles the Bold’s sister, sent frantic appeals for Burgundian intervention. Similar messages came from the Count of Romont, whose castle at Morat had so recently fallen.

Charles, knowing of French money being handed over to the Swiss, and affronted by Swiss aggression, resolved on an expedition as soon as Lorraine had been pacified. Thus, by the winter of 1475–76 he wrote, “I am going to deliver and avenge my own subjects and those of Savoy, harassed, injured and oppressed by the Swiss and their allies.” On a more cautious note, he reminded Panigarola, the Milanese ambassador, “against the Swiss it will never do to march unprepared.”

He mobilized his fine army and raised the feudal levy to protect his own lands as he marched east. Sending 3,500 men to join Romont near Geneva, he left Nancy with 20,000 men on January 11, 1476.

These were some of the best troops in Europe. In addition to troops raised in his own territory—which varied in quality from reluctant Flemish levies to the superb men-at-arms of Charles’s own household—Charles had supplemented his forces with the very best mercenaries Europe had to offer, paid for by an overflowing treasury. There were infantry crossbowmen and mounted men-at-arms from Italy, handgunners from Germany, archers from England, and pikemen from the Rhineland. Added to this, Charles had accumulated some of the finest artillery the world had ever seen, some three hundred pieces for siege and field work.

Before this impressive host the Swiss recoiled, evacuating garrisons and frantically calling in contingents to form their own field army. But at Grandson, which had fallen to the Swiss in the spring of 1475, the garrison—five hundred men under Hans Wyler—was told to hold fast and await relief, in effect buying time with their lives.

On the night of February 24, two of the garrison guards were lowered by ropes and brought news to Scharnachtal, the Swiss commander, of the plight of the garrison, stressing that if relief did not arrive before the end of the month it would have to surrender. Scharnachtal urged the cantons to hurry forward their contingents so that he could begin field operations.

Meanwhile, he resolved to attempt to deliver supplies to Grandson by water. Four boats set out from Neuchatel on the 25th but were intercepted by Burgundian vessels and pelted both by shot from the Burgundian cannon and from infantry running along the shore. To the dismay of the garrison, watching high above from the castle walls, the Swiss boats turned back.

On Ash Wednesday the garrison surrendered unconditionally, 412 of them trailing past the duke and up through the winding streets of the town. Charles ordered them executed to a man; perhaps, listening to the pleas of people from the Pays de Vaud who had suffered at Swiss hands, perhaps hoping to set an example and awe the Swiss into submission.

It took four hours for the Burgundian provost and his men to complete the grim work, the Swiss prisoners being roped together and hanged in the trees that surrounded the camp and ran along the lake. An eyewitness recorded the scene: “Four hundred men were hanged in nearby trees by three executioners, and others were drowned in the lake. The hardest of hearts could not have felt pity at the sight of these poor men swinging from the branches of the trees; so many were they to a branch that frequently they would fall to the ground and, half dead, be mutilated by their cruel enemies.”

Just two of the garrison were left alive to run and tell the tale to their comrades. Charles celebrated his success, writing to the Regent of Savoy and expressing his certainty that he would now meet and defeat the Swiss field army. The Milanese ambassador was less sure, finishing a letter to his masters with the Latin phrase “bellorum eventus dubii sunt” (war is a thing of chance).

But the Swiss had left nothing to chance and had moved to Neuchatel in preparation for a general advance against the Burgundians. Troops had flooded in from Zurich (Hans Waldmann’s contingent), Lucerne, Schwytz (Rudolf Reding’s troops), Basel, Strasburg, Freyburg, Solothurn, and Bienne. Most of these were infantry armed with the redoubtable pike, but there were also 60 cavalry from Basel, 300 from Strasburg, and 120 Austrian volunteers under Hermann von Eptingen.

Charles was informed of the movements at once but he was still unsure of the scale of the enemy before him—some 19,000 men—when he rode out on reconnaissance, on the morning of March 1, along the Grandson–Neuchatel road. He sent a detachment of four hundred men under Georges de Rozimboz over the crest of the foothills to garrison a small castle at Vauxmarcus and watch the bridge over the Ruaux stream. Charles then returned to camp, pleased with his dispositions, and hoping to move his entire army along the same road on the morrow. He intended to seek out the Swiss and bring them to battle.

But the Swiss were coming on fast, shouting “Grandson! Grandson!,” and, in the gloomy morning of the 2nd, launched a dramatic assault against the Burgundian archers in Vauxmarcus. The Swiss were beaten off. But their vanguard then skirted round the obstacle and brushed against the Burgundian archers defending the bridge. These were chased away until, at 11:30 am, the most forward elements of the Swiss spilt over the crest of Mount Aubert and caught sight of the Burgundian host, collected on the plain of Grandson below, preparing to advance. Recovering from their surprise, the Swiss sent messengers back to their main body urging them to quit the assault on Vauxmarcus and hurry forward to their assistance.

Charles, also surprised at seeing the Swiss so soon before him, made rapid dispositions to meet the eight or nine thousand pikemen. These pikemen, formed up in their traditional phalanx beneath 30 green banners and a white flag, and flanked by a small number of handgunners, ground to a halt and fell to their knees, in prayer. According to the Swiss chronicles Charles is supposed to have cried out that they were begging for mercy; whether true or not, he spurred his gray charger forward and directed the men-at-arms on his left flank, under Louis de Chalons, Prince of Orange, to charge the enemy.

The enthusiastic Burgundians cheered, calling out, “Our Lady, St. George and Burgundy!” The Swiss quickly formed up in preparation for the coming onslaught, their commander, Hassfurter—a man with a huge beard according to Panigarola—riding around the formation to check its alignment. The pikemen in the first rank each rested the butt of his lance against his right foot and extended his left leg; the ranks behind held their weapons horizontally and, behind them, stood the vaunted halberdiers.

As the enemy artillery opened up, this compact square began to suffer casualties. Soon, however, the Burgundian cavalry came on forcing the guns to fall silent for fear of hitting their own men. Their horses refused to press against the savage points of the pikes and the mass flowed around the phalanx to the jeers of the Swiss.

Still the Burgundians persisted and the 28-year-old Louis de Chalons spurred his horse against the pikes. His mount reared in agony and vaulted into the mass, crushing a number of pikemen; Louis grabbed the standard of Schwytz but, unbalanced in the struggle, toppled from his horse at the same moment. He was dispatched with one blow from a halberd. The Burgundians withdrew in disorder but their artillery opened up again and their archers, particularly a body of English archers under Sir John Middleton, began to inflict serious casualties.

Charles, taking his banner in his own hands and escorted by trumpeters in blue and white coats brandishing silver trumpets, now led a charge in person. The duke’s horse was killed as the infantry and cavalry clashed. In the confused fighting, he was remounted but the charge was again turned back.

Encouraged, the Swiss now advanced. Charles sent orders for his center to fall back and lure the Swiss still farther forward. As the phalanx advanced, it found itself menaced by the Burgundian right and left flanks. Charles was just preparing to send his left flank against the Swiss in a coup de grâce, when the entire Burgundian army received a tremendous and sudden shock. Above them, on the crest of the range of hills, appeared the Swiss main body, charging forward in its measured pace and accompanied by shouts of “Grandson!” and the blaring of mountain horns.

The Burgundians, disheartened by their cavalry’s defeat and unnerved by the retreat of their artillery and infantry supports, began to break formation and run for the rear. “From all sides rose the cry, ‘Save yourself if you can!’” wrote Panigarola. The infantry on the right and left flanks were the first to do so, fleeing through the hamlet of Onnens and on through the Burgundian camp beneath the walls of Grandson. The cavalry and artillery, abandoning their guns, followed suit, and the whole fled in panic. Charles attempted to hold the bridge over the Arno stream but found himself deserted by his army and he, too, fled the field.

Charles’s sumptuous camp and artillery fell into Swiss hands as did some two thousand camp followers. The riches of the camp effectively put an end to the Swiss pursuit, and the French chronicler, Commines, well acquainted with the battle and the participants, throws light on the spoils that fell into the hands of the Swiss: “So the Germans [Swiss] captured his camp, his guns and all the very numerous tents and pavilions belonging to the duke and his men, as well as an enormous amount of other goods. The duke’s largest diamond, one of the biggest in Christendom, with a pearl pendant, was picked up by a Swiss then put back in its box and thrown under a cart. Then he came back to look for it and offered it to a priest for a florin. The latter sent it to the leaders who gave him three francs for it. They also acquired the identical rubies known as the Three Brothers, another ruby called the Hotte, and another called the Ball of Flanders, which was one of the largest and finest ever found, as well as other priceless treasures which have since taught them what money is worth.”

A great and veteran army of 20,000 men (Romont’s detachment was still absent) had been defeated for two hundred Swiss casualties. The Burgundian loss had been light—although they had lost a number of notable commanders, including Louis de Chalons, Piero de Lignana, Quentin de la Beaumme, and Jean de Lalaing—but all their guns were captured, and the remnants of the army, shedding deserters at every step, retired into Savoy to lick its wounds. The duke was livid, ranting about “those vile Swiss” and “the damage done to his honor by the cowardice of his own troops.” Charles never overcame his rage but, drawing in reinforcements and renewing his artillery from his arsenals, he resolved to try for battle again. The Swiss returned home with their spoils.

A great and veteran army of 20,000 men (Romont’s detachment was still absent) had been defeated for two hundred Swiss casualties. The Burgundian loss had been light—although they had lost a number of notable commanders, including Louis de Chalons, Piero de Lignana, Quentin de la Beaumme, and Jean de Lalaing—but all their guns were captured, and the remnants of the army, shedding deserters at every step, retired into Savoy to lick its wounds. The duke was livid, ranting about “those vile Swiss” and “the damage done to his honor by the cowardice of his own troops.” Charles never overcame his rage but, drawing in reinforcements and renewing his artillery from his arsenals, he resolved to try for battle again. The Swiss returned home with their spoils.

By the middle of March Charles had called in two thousand men from Lorraine and as many pikemen—arming them with pikes “longer than those of the Swiss”—from Ghent and Guelders, and had contracted for more Italian (termed “Lombards” in Burgundian records, usually men from Milanese and Venetian territory) mercenaries. He brought forward artillery from Luxembourg and demanded more money from Flanders and Dijon.

Preparing to renew the campaign, he moved forward to Lausanne and began to weld a powerful new army together. He was faced by considerable difficulties—the king of France had launched another diplomatic offensive, the area around Lausanne was soon stripped of food, and his army was restless and mutinous over arrears of pay. The Milanese ambassador wrote that the Italian mercenaries were particularly unhappy, and were saying openly, “when we’ve got our money, we’re going.”

In April fighting broke out between English archers and bands of Italian infantry, armed gangs running through the camp. Seven archers were killed, and only when Charles brought in his personal bodyguard and executed one of the ringleaders, was the trouble ended.

Nevertheless, by late May, after a series of reorganizations and issuing of strict instructions on discipline, Charles’s army was deemed ready. The bearded Charles—he had vowed not to shave until he had beaten the Swiss—quit Lausanne and with 23,000 men, according to the report of the Duke of Taranto, advanced directly toward Berne. His movements were provocative and, in a ploy designed to draw the Swiss down upon him, he lay siege to the castle of Morat with its recently strengthened garrison of 1,500 men under Bubenberg.

The Burgundians arrived below Morat on June 9 and Charles paraded his army to intimidate the Swiss. Morat lay on the southern shore of Lake Morat, an obstacle that completely enveloped the castle and town from the north. The Burgundians quickly deployed, surrounding the town and commencing siege operations. Charles posted the newly arrived Romont and the Savoyards (numbering eight thousand) to the northeast of Morat while assigning a considerable body of Italian infantry—crossbowmen adept at siegework—to the siegeworks proper. These Italians, commanded by Gian Francesco Troylo and Antonio de Lignana (his brother, Piero, had been killed at Grandson), numbering six thousand men, therefore effectively formed Charles’s center as he placed his camp on the shores of the lake to the southwest of the castle.

His camp was dominated by a plateau, and upon these heights Charles built a strong line of entrenchments and palisades, complete with artillery and earthworks, designed to meet and defeat the Swiss attack which was expected from the east any day. Charles’s troops suffered from the severe disadvantage that between them and the oncoming Swiss relief force was the wood of Morat, a thick and obscure forest that served to screen Swiss movement. This wood was not defended, although archers were placed there to warn of the Swiss approach.

And the Swiss were approaching fast. On June 18, just as a Burgundian assault on Morat was being beaten off, the troops of the cantons had gathered. Added to the formidable pikes were five hundred Austrian cavalry under Thierstein and three hundred under the exiled Duke René of Lorraine. These cavalry would fight beneath René’s banner which, suitably, bore the motto “All for One.”

By the 20th the Swiss and their allies were within striking distance but held back, waiting for the Zurich and St. Gall contingents to join them. This they soon did, bringing the total to 25,000 men. Charles was unaware of Swiss strength but knew the enemy was close; he assumed that the Swiss had sent a small force to lure him away from the siege.

The Swiss, however, knew their own strength and now prepared for battle, sending skirmishers against the woods on the 21st. In the evening the fighting died down, although Swiss mountain dogs continued to scrap with Burgundian camp dogs along the fringe of the forest.

Late on the morning of Saturday, June 22, the Swiss vanguard under the 42-year-old Halwyl began to move forward. The Burgundians behind the palisades had been under arms since dawn and, as noon approached, Charles had his men stand down and seek some respite from the rain in the Burgundian camp, leaving just two thousand men to man his main defenses. But as the Swiss burst from the woods the alarm was sounded and the Burgundians were thrown into turmoil. The Milanese ambassador was present: “Towards noon the rain ceased. Just then we saw emerging from the woods, and advancing towards us, a phalanx of Swiss with their long pikes, all on foot, with handgunners going before them. Close by was another formation and between them was a body of about 400 cavalry. These advanced but then waited for all of the infantry to catch up.”

The Swiss, 12,000 of the vanguard and main body, came straight against the palisades in a show of typical audacity. The Burgundian artillery managed a general discharge, despite the wet weather, and tore bloody lanes in the Swiss ranks, “I saw heads carried off and bodies torn asunder,” wrote one Swiss soldier.

The allied cavalry also sustained casualties and the Duke of Lorraine’s horse was killed. The Duke was remounted on a gray charger called la Dame. Despite the fire, the infantry came on, clambering over the defenses before the artillery could fire another round. There was some brief hand-to-hand fighting, the Swiss two-handed swordsmen doing great execution, before the Burgundians broke and fled. As they scurried downhill, toward their camp, they ran into Charles and the main body coming up the slope and sowed disorder in their ranks.

The Burgundians still came on and their cavalry managed to rout the confederate cavalry. However, the Swiss pikemen beat the Burgundians back and themselves advanced, pouring down the slope and pushing all before them. In front of his camp Charles had drawn up the English archers. As they caught sight of the advancing enemy they prostrated themselves on the ground and etched the sign of the cross in the earth. Then they had enough time to discharge one volley before the Swiss were upon them, killing their commander and pushing the disordered mass through the camp, hewing and stabbing as they did so. The Swiss pursued as the Burgundians fled toward Avenches, their cavalry cutting through the fugitives and trampling upon them. The Milanese ambassador wrote: “I made my escape whilst the enemy was already in amongst the tents, cutting throats. The ambassador of the king of Spain, who was with me, received two sword blows to the head and his horse was wounded. As for myself, I spurred on my horse and, thanks be to God, I saved my life. But I will never forget such dangers.”

The Count of Marles was killed after vainly imploring for mercy and offering 25,000 ducats to save himself. Jacob van der Maas, the great standard bearer, sold himself more dearly, wrapping the standard of St. George around himself and fighting to the death. Despite the terrible destruction of Charles’s main body, these events paled in comparison to the fate awaiting his center.

As the Swiss were storming the palisades, the garrison of Morat issued out and attacked the Italian trenches. They were beaten off and thrust back into the castle. The triumph was short-lived, however, for the Swiss rear guard had also skirted round the wood and now directed a charge against the Italian position.

Caught between the Swiss phalanx and the castle, with their backs to the lake of Morat, the Italians were in an unenviable position. The Swiss attack was briefly halted by an earthworks but the obstacle was quickly overcome and the Swiss literally rolled over the Italians, plowing through their ranks and heralding the start of a general massacre. A good number attempted to hide in the village of Faoug. They were hunted out mercilessly, even being smoked out of chimneys and shot off roofs.

The bulk of the Italians attempted to flee toward Avenches but found themselves barred by the Swiss vanguard and trapped against the lake. Most fell in an unequal combat on the marshy ground by the lake. Some hid themselves in the walnut trees that ran along the shore. A few, desperate, waded out in an attempt to escape, but these either drowned or were cut down by their pitiless pursuers, who waded in after them or shot at them with handguns or crossbows. Scarcely a man escaped from a force of six thousand, because the Swiss took no prisoners.

The only part of the Burgundian army to escape relatively intact was the corps of the Count of Romont which, seeing the fate of the rest of the army, managed to slip away to the north, work its way around the lake, and make good its freedom.

The battle had lasted an hour; the carnage that followed just over five. That evening the Swiss, now joined by the 1,500 men of the garrison, reveled in their success. By the lake they amused themselves by picking up crossbows discarded by Charles’s men and shooting at the Italians hidden in the walnut trees. The Burgundian camp was pillaged, although the spoils were much less than those of Grandson, and the Burgundian women found in the camp— sutlers, prostitutes, and soldiers’ wives—were handed over for the pleasure of the soldiery.

Victorious dispatches were sent to the leaders in Berne, estimating the Burgundian loss at 10,000 men. A more detailed count over the following days revised this total to 22,000 casualties. All of these were thrown into unmarked graves. The Swiss themselves had lost three thousand men, mostly in the fight for the Burgundian palisades.

In 1480, the Swiss authorities unearthed the thousands of bones that had littered the field and piled them into a mound capped by a small monument. In March 1798 troops taking part in a more successful invasion of Switzerland— infantry of the armies of Revolutionary France —demolished this “insulting” monument. Bones were still littering the ground when Byron visited in 1816, a gloomy testament to a slaughter by a now-placid lake.

Charles and his army fled to Gex, the Duke pausing briefly to say Mass and to order his half-brother, The Great Bastard Anthony, to rally the survivors at La Riviere. His personal escort consisted of just a hundred horsemen. From Gex he pushed on to Salins and arrived delirious and “not seeming to be himself.” He again busied himself with raising troops and demanding money from his reluctant parliament; but Burgundy was exhausted by defeat and, from all sides, his enemies were closing in.

The Swiss pursuit had ended on the fringes of the battlefield and, content with victory, many of the contingents simply returned home. Those that remained, chiefly that of Berne, pushed on and brutally punished Savoy for its alliance with Burgundy by sacking Lausanne. Almost simultaneously, Lorraine rose in revolt, calling Duke René back to his homeland and besieging Burgundian garrisons.

By the autumn of 1476 Savoy and Milan had quit their alliance with Burgundy, France was paying the Swiss a handsome pension and urging them to supply the Duke of Lorraine in his war with Charles, and Charles himself had set out with a small and imperfect force in an attempt to relieve his garrison at Nancy. Unfortunately the garrison of English archers surrendered before the Burgundian army arrived, but Charles pushed on and outmaneuvered René who, throwing a garrison into Nancy, retreated as fast as he could. Only with the intervention of the Swiss was the war decided, René returning to the field in December at the head of 20,000 Swiss, German, French, and Alsatian troops. Charles, with 11,000 men—a number diminishing every moment as his officers and men deserted in droves—again found himself caught besieging a town.

On Sunday, January 5, 1477, Charles drew his army up behind a stream and, mounted on his black charger, Il Moro, prepared for his final battle. He placed his infantry—mostly Flemish pikemen—in the center and Lalaine’s cavalry on the right. On the left, on the banks of the Meurthe, he placed more horsemen under the faithful Jacopo Galeotto.

The forces under the Duke of Lorraine came forward, rushing through the village of Saint Nicholas. An eyewitness, Molinet, in an account written shortly after the events, takes up the story of the battle of Nancy: “The Swiss were in two bands, of which the Count of Tierstein and the Governors of Friburg and Zurich commanded one and the leaders of Berne and Lucerne the other. At around noon the whole host moved forward.

“The Duke of Burgundy had come out from his camp and was formed up in a field with a stream called la Magdelaine between himself and the others and behind two thick hedges. On the main road he had placed his artillery and as soon as one band of Swiss showed themselves the artillery of the said duke fired upon the Swiss and hurt them greatly. They left the road and passed through the woods, marching against the duke’s flank.

“Meanwhile, the Duke of Burgundy deployed his foot archers between two wings of horsemen under Jacques Gallyot [sic], an Italian captain, and Messire Josse de Lalaine.

“As soon as the Swiss found themselves alongside the duke’s army, they turned to face the duke and his army and, without pausing, marched directly to the attack; as they came closer they discharged their handguns and at this discharge the whole of the duke’s infantry fled and the Swiss band in the center now advanced. Jacques Gallyot and those that had remained with him, charged down upon them, but unsuccessfully and the said Jacques was killed.

“The other [Burgundian] wing did the same but the Swiss were not to be stopped and the duke’s horsemen followed his infantry in flight and the whole made off towards Buzore, half a league from Nancy and where the road to Cherouville and Luxembourg was.”

The flight was terrible as a German eyewitness records: “They tried to save themselves, each as well as they could. Our cavalry hunted them; Burgundians were cast down, knocked down to the ground dead; riderless horses fled to left and right; armor, lances, javelins, guns and other things littered the ground from their position to the bridge at Bouxieres. The pursuit continued right up to Mousson and even to the gates of Metz and as long as the day lasted we killed a good number of men-at-arms and noblemen.”

The Duke himself was surrounded by confused fighting but all accounts testify that he fought heroically, repeatedly leading his cavalry forward in a desperate attempt to protect his army’s third flight. After the Burgundians had quitted the field, no more was heard of him.

That evening, and throughout the following day, the site of the battle was thoroughly stripped of any kind of trophy by the people of Nancy and by Swiss and German pillagers. There, on a field strewn with corpses, “some with their faces cut from temple to teeth, some with their arms hacked off, others covered in stab wounds,” a young page called Baptiste Colonna swore he could find the place of the Duke’s last stand.

The next morning, “accompanied by many great lords,” he was escorted out and made his way to the place. He found the corpse of his master in a ditch by the banks of the St. Jean stream to the rear of the Burgundian position; it was naked, stripped by pillagers, and a tremendous wound had cut open the face from “above the ear to the teeth.” Dogs and wolves had torn at the Duke’s flesh but he was recognizable and his body, wrapped in a blanket, was carried into Nancy and laid on a table in a house in the street of Ville-Vieille. It was an ignoble end to an astonishing career.

With the death of Charles the Bold, the duchy of Burgundy came crashing down. Two months after the battle at Nancy, Louis XI invaded Burgundy and Franche-Comte; Charles’s daughter, Marie, held the Netherlands but called upon her fiancé, none other than Maximilian of Hapsburg, for protection. They were married in Ghent in August, effectively passing the entire region into the hands of the Hapsburgs.

Charles had opened his campaign against the Swiss in January 1476; a year later he was dead and his duchy no more. For Europe, 1476 marked the beginning of a bitter war, a conflict that would recast the continent. It was a struggle that was to be overshadowed by the wars that followed—the Italian Wars and the mass destruction of the Reformation—but that, nevertheless, at the time, seemed unprecedented in their fury and contempt for human life.

What did Charles’s contemporaries make of this fall from glory? Commines, reflecting on the defeat and the wonderful opportunity presented to France by Charles’s death, summed up the Duke of Burgundy’s last year as follows: “He craved great glory, and it was for this reason more than for anything else that he was led into these wars. He would have liked to resemble those princes of antiquity about whom so much has been said since their deaths. He was as daring as any man of his generation. Yet all his schemes are finished and they all turned out to his dishonor and shame; for those who win always get the honor.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments