By Jon Diamond

The U.S. military employed an organized system for the treatment of soldiers severely wounded while fighting in the Pacific, including their evacuation stateside if needed. This system was based on the concept of medical care echelons.

Echelon I comprised an aid station/unit dispensary, while Echelon II referred to collecting or clearing stations. Mobile hospitals for evacuation, emergency surgery, and convalescence made up Echelon III. Echelon IV was composed of the general hospitals, hospital centers, and station hospitals. Echelon V was made up of hospitals in the Zone of the Interior.

It should be emphasized that this nomenclature was devised for medical care for the wounded mostly in the European Theater of Operations (ETO); however, it was also applied for the treatment of wounded American soldiers, Marines, and sailors on remote jungle battlefields in Burma and the South Pacific.

Teeming With Environmental Hazards

Often routes through the jungle battlefields of Burma and the South Pacific islands were no wider than a column of troops trekking in single file. Allied soldiers required mules and horses to carry the heavy equipment and supplies. In addition, wild vegetation—12-foot tall, razor sharp elephant grass, dense bamboo forests, and mangrove swamps—presented further obstacles for the troops. Wild animals and venomous snakes inhabited many areas crossed by troops of both sides and caused non-battle casualties. Disease-laden mosquitoes, poisonous scorpions, biting flies, and leeches infested the impenetrable forests and swamps.

One salient issue that emerged for these remote, often impenetrable battlefields was what to do with the wounded. The Allies had paid a high price in military personnel and negative morale after the debacles of the British retreat in Burma in 1942 and Operation Longcloth in 1943, conducted by Brigadier Orde Wingate and his Chindits. Simply leaving the wounded and accompanying medical caregivers with either local villagers or to the Japanese resulted in executions and atrocities and was no longer an option.

The New Guinea Campaign

General Douglas MacArthur’s advances in New Guinea in 1943-1944 and the Allied invasion of northern Burma were to be true offensives and as such would possess frontline and rear echelon capabilities of treating and evacuating wounded troops. Control of the air and the emergence of larger fleets of air transport craft to ferry the wounded from the front line to the rear echelon would add greatly to the care administered to the wounded.

A typical pattern of events occured once an infantryman became wounded during combat. Within minutes of someone “getting hit,” a company medic or aid man would cautiously crawl to the wounded soldier, assess the extent of the wound, and begin the actual treatment process, which at this level would include field dressings and tourniquets to stop the bleeding and placement of antibiotic sulfonamide powder onto the wound, coating it immediately to minimize the likelihood of infection.

With time, more potent antibacterial agents such as penicillin and streptomycin were being used in rear-echelon areas. At this initial juncture of treatment in the jungle, medics learned that dressings had to be dyed khaki or green because Japanese snipers took aim at white bandages. At times, even casualties tore off their white bandages to prevent becoming easy targets.

Survival By the Numbers

Survival depended on a number of factors, including the type and location of the wound and the proximity to medical care. Soldiers in the Pacific usually fared worse than their counterparts in Europe. An actuarial approach was applied to the chance of survival after being seriously wounded. If appropriate and adequate treatment were initiated within an hour, there was a 90 percent chance of recovery. After eight hours the likelihood of survival fell to 25 percent. Thus, rapid movement of the wounded to advanced field hospitals increased the survival chances of battlefield casualties considerably.

After being initially treated by a combat medic, if the wounded soldier was fortunate, a litter team of four men from a forward aid station would be summoned, usually by portable radio or field telephone immediately after first aid was applied. Again, depending on the severity of any ongoing combat, the litter team could often arrive within 30 minutes of the wound being inflicted. The litters would be carried back to wherever the aid men had left their jeep or mules, often a distance of 25 to 100 yards or more.

Processing the Wounded

The litter would frequently have to be carried up and down ravines, making it extremely uncomfortable for both the wounded and the litter team. Since the combat front was literally yards away, a four-man litter team was usually accompanied by one or two infantrymen with Thompson submachine guns, well suited for close combat defense in the jungle. From there, the wounded man could be transported to a battalion aid station about a mile away from the front line.

An injection of morphine was accompanied by a note advising subsequent medical personnel that the narcotic had been given. The note was usually tagged through the wounded soldier’s uniform buttonhole. At the battalion aid station, if pain were still paramount, additional morphine was given, followed by a surgeon’s examination of the wound and removal of any evident debris such as shrapnel, rock, or wood. Fresh bandages were applied and anti-tetanus shots given. Any fractures were reduced and splinted. If massive blood loss or shock was evident, blood plasma or albumin infusions were administered to maintain adequate blood volume and blood pressure. Again, the treatment rendered and initial diagnosis were tagged to the wounded soldier via his uniform’s buttonhole.

After initial stabilization at the battalion aid station, the wounded soldier was moved an hour or two later via jeep, ambulance, litter, or “piggyback” in oppressive heat or rain through jungle to a divisional forward clearing or collecting station that might also house a portable surgical hospital, usually located 1,000 yards to the rear.

The divisional forward clearing or collecting station was still close to the front, and portable surgical hospitals were often housed in sandbag-lined dugouts or bunkers with coconut log roofs and additional sandbags to withstand enemy mortar rounds and artillery fire. If the divisional clearing or collecting station were operating during an advance, it might simply be out in the open under the jungle canopy. Casualties were sorted and triaged again at these divisional forward stations.

Ideally, those needing immediate surgery went to the portable surgical hospitals while those not so seriously wounded or too ill to remain near the front were sent to rear clearing or collection stations. When the 3rd Portable Surgical Hospital arrived, after flying from Port Moresby into Dobodura, New Guinea, it carried its 1,250 pounds of equipment in pack frames and hauled it to the front near Buna Mission by mules. Once there, the medical personnel set up close to the divisional forward clearing or collecting aid station, which was only about 300 yards from the entrenched Japanese positions.

It was the mission of the surgeons at these portable surgical hospitals to provide emergency lifesaving and stabilizing treatment. They did not hold any soldiers who were ill with fever or those who could safely travel to the rear. Throughout the day and night, bullets struck the tents. During a single week, its first on the line, 3rd Portable Surgical Hospital personnel performed 67 major surgical procedures, including amputations, bowel resections, and other operations that would challenge a metropolitan urban hospital’s capabilities.

It was at these divisional clearing or collecting stations that a more thorough examination of the wound and triage would be conducted and, if needed, an emergency operation performed. The surgical team consisted of the head surgeon, his assistant surgeon, an operating room scrub nurse, and someone administering the anesthetic. Medical personnel prepared casualties for evacuation by jeep, boat, or litter to ambulance loading points for transport to rear collecting stations that stood under canvas approximately 21/2miles behind the initial battalion aid stations.

Additional emergency care, mostly plasma and more morphine, was provided at these rear collecting stations. If further surgery was required, updates were made to the wounded soldier’s medical tag. Then any available transportation took the casualties to field hospitals, usually also under canvas approximately three to four miles to the rear.

Some portable surgical hospitals were present at the field hospital locale if emergency operations became necessary. Just because these field or portable surgical hospitals were in the rear did not exclude them from harm’s way. Field and portable surgical hospitals were bombed and shelled unmercifully by the Japanese. The hazards faced by medical personnel were, in some cases, similar to the medics being shot at while carrying litters or dragging wounded to battalion aid stations or dressing wounds in the field.

Allied surgeons working in Burma began to develop alternative treatment methods more suited to jungle conditions. Limb wounds were left open, and damaged muscle and bone were excised. Sulfonamide powder and a protective layer of lint covered with Vaseline were laid on the raw surface before the appropriate splint or plaster cast was applied. This was done to relieve any tension in a wound that would develop if immediate closure were performed in the hot, humid climate. Even some abdominal wounds were left partially open, as infections often developed if wounds were completely closed. As with limb wounds, the procedure was to clean the wound and leave it open for around 10 days, after which it could be sutured.

By late 1944, radical excision of wounds, improved evacuation (preferably by air), and the introduction of newer antibiotics such as penicillin improved survival rates. Most jungle battlefield casualties were then receiving treatment within hours due to the increased mobility of field hospitals and the extensive use of air transport as ambulances.

Medical personnel preferred air over sea transport, since evacuation by ship entailed many transfers of the wounded from ambulances to lighters and from lighters to ocean craft. Journeys by ship were long, usually two to three days as compared to four hours by air across the same 600 miles of ocean. Air transport also played a prominent role in medical supply. The same aircraft that brought in supplies ferried out casualties. Air evacuation to a base hospital in the rear echelon of the battlefield or stateside was crucial when dealing with great distances.

A series of photographs taken by frontline soldiers of the U.S. Army Signal Corps on the island of Bougainville aptly demonstrates the process of rendering care to wounded soldiers at all medical echelons. Bougainville is the largest island in the Solomons. On November 1, 1943, the 3rd Marine Division landed there to fight the Japanese. The terrain, both swampy and hilly, posed a greater operational obstacle to the invading American soldiers and Marines than the 20,000 Japanese garrisoned on the island.

In the accompanying series of photographs, a detachment of American infantrymen of the 37th Infantry Division aggressively patrols the outside of its perimeter in single file in late 1943. When the leading men enter the tangle of trees and vines, a Japanese mortar round suddenly explodes, blowing both mud and vegetation high into the air. At the same time, Japanese snipers open fire on the detachment, and Private Homer Connell of Columbus, Georgia, one of the last men in the patrol, is hit just as he is about to enter the jungle. He grabs his right hip, where he is hit by an enemy sniper’s bullet and calls out for help as he edges his way to cover and first aid.

A combat medic, Corporal William Ackley of Cleveland, Ohio, runs to the aid of the fallen Private Connell, reaches for the soldier’s field dressing pouch, and begins to assess the extent of the injury. After administering a dose of morphine, the combat medic pins an empty syrette to the jacket of the wounded soldier to clearly exhibit that he has received a narcotic dose and to avoid repetitive dosages, which could cause accidental death from respiratory depression. The tag on Connell’s jacket also indicates that he received the narcotic and other pertinent data.

Private Connell and another wounded soldier begin their journey to a battalion aid station just behind the front lines. Litter bearers are careful to keep the men from being bounced too vigorously during the trip up a hilly jungle trail into the perimeter, indicated by the barbed wire. All four litter carriers have their M1 carbines slung over their left shoulders, while the soldier leading the party has a Thompson submachine gun for close-quarter jungle combat.

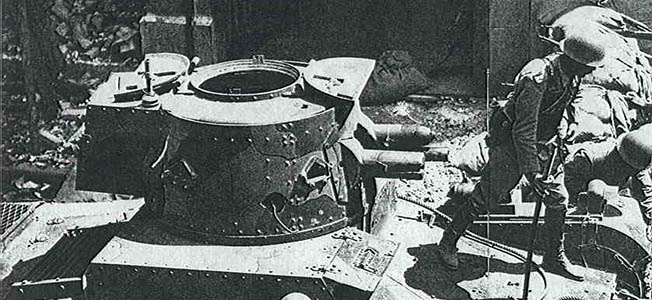

From the battalion aid station, the wounded Private Connell, while still on a litter, is taken by jeep to a divisional forward clearing or collecting station and carried into the underground portable surgical hospital, which is protected on all sides and on top from anything but a direct hit from an enemy artillery shell or bomb. The wounded soldier is immediately made ready for surgery. The anesthetic is administered, and the surgeons go to work, saving the wounded soldier’s life. The operating team at this portable surgical hospital was made up of both officers and NCOs and included the main surgeon, his first assistant surgeon, scrub nurses, and the anesthetist.

It was not until World War II that the enemy killed more American troops than disease did. Thirty percent of those wounded in action during World War II ultimately died; however, the vast majority survived. During most campaigns in World War II, for every single American soldier killed four or five were wounded. Of these, one would be seriously wounded and would no longer see combat, while another would have serious wounds taken care of to such a good extent that a return to action was possible.

The U.S. Army had planned for the proper care of the wounded soldier on the battlefield. In a division consisting of 14,000 men, a medical battalion of 1,000 soldiers was included. During any major U.S. Army assault, each battalion would have an attached medical platoon. Unarmed medics were ubiquitous in combat, even during amphibious assaults where they would be present in the first wave of troops landing under fire. Beachhead casualties were particularly hazardous because there were so many in a confined area, and the gravity of the situation was made worse by persistent enemy fire and successive waves of troops coming ashore.

The valor and heroism of these combat medics, physicians, surgeons, and nurses cannot be overstated as they worked under extreme conditions to render lifesaving care and dramatically increase the chance of surviving a wound on a remote jungle battlefield in Burma and the South Pacific islands.

Jon Diamond practices medicine and resides in Hershey, Pennsylvania. He has written numerous articles for World War II History as well as Osprey Command Series titles on Archibald Wavell and Orde Wingate.

THANKS FOR SHARING AN THANK TO THE MANY THAT SERVED!!!

God Bless those who have and continue to save so many.

Thanks, Doc and to all the other Corpsmen past and present. Semper Fi!

America has always endeavored to provide the best care to her battle-wounded. The next best improvement came with the helicopter ‘dust off’ romanticized in ‘M.A.S.H.’ This practice helped to extend that ‘Golden Hour’ in which, if emergency treatment was effected helped to extend survival rates greatly. Much laud to our Medics, Corpsman and Combat Nurses of all ranks and stripes.

G4083 HMC

Unsung heroes, indeed.