By Allyn Vannoy

Before there was an air-sea battle at Midway or in the Coral Sea, American aircraft carriers were launching operations against Japanese bases in the South Pacific, with the Japanese fighting to defend their gains.

One such action took place east of the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul in February 1942. In hindsight, it should have been a warning to the Japanese of things to come.

U.S. Navy fighter squadron VF-3’s carrier, the USS Saratoga (CV-3), had taken a torpedo on Sunday, January 11, 1942, approximately 420 miles southwest of Hawaii and would be out of action for several months while undergoing repairs.

In the early months of the war, the USS Lexington’s own VF-2 was still operating obsolete Brewster F2A Buffalo fighters. While the Lexington’s fighter squadron was removed to exchange their F2As for Grumman F4F Wildcats, VF-3, under Lt. Cmdr. John Thach, was transferred to the Lexington, part of Task Force 11. Thach also led one of the squadron’s six plane divisions, the squadron’s other two divisions being led by Lt. Cmdr. Donald Lovelace, executive officer, and Lieutenant Noel Gayler, flight officer.

Task Force 11 to the Solomons

Task Force 11 comprised the carrier Lexington (CV-2, affectionately called The Lady Lex and commanded by Captain Frederick C. Sherman), the heavy cruisers Minneapolis and Indianapolis, seven destroyers, and the fleet oiler Neosho. The Lexington’s air group included 18 fighters, 37 dive bombers, and 13 torpedo bombers.

Task Force 11 left Pearl Harbor on January 31. The Lexington had been assigned the task of penetrating enemy-held waters north of the island of New Ireland. On February 6, TF 11’s mission was modified to cooperate with the newly created ANZAC Command to blunt Japanese advances toward the New Hebrides and the line of communication between Pearl Harbor and Australia. On February 10, the task force was reinforced by the addition of the heavy cruiser San Francisco and two destroyers.

With Japanese advances in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, the U.S Navy was eager to hit back. The task force was ordered to conduct offensive operations in the Solomons-Bismarck Archipelago area to strike the Japanese base at Rabaul on the eastern end of the island of New Britain.

Plans were made to pass east of the New Hebrides and the Solomons to a position where Rabaul could be attacked from the northeast. An air strike was to be launched on February 21, to be followed, depending on the situation, by a shore bombardment by a heavy cruiser and two destroyers.

Intelligence indicated that there was no threat from Japanese carrier forces in the area, as they were reported to be operating in the Dutch East Indies. On February 17, the heavy cruiser Pensacola and two destroyers also joined the task force.

While concerned with the defense of the Bismarcks, the Japanese were planning to occupy Lae and Salamaua in eastern New Guinea, along with Tulagi in the southern Solomons, scheduled for March and April. This was to be followed by the seizure of Port Moresby on Papua’s southern coast.

To provide air support, in early February the Japanese command began concentrating units from the 24th Air Flotilla at Rabaul. Two naval air groups, one with fighters and one with medium bombers, wold ultimately operate from there.

Using radio interceptions, the Japanese determined that an American carrier task force had departed the Hawaiian Islands in early February. On February 14, alerts were given to their forces at Truk and Rabaul and, late on the afternoon of February 19, a Japanese station on a small island 160 miles southeast of Truk reported sighting two enemy destroyers—information that later proved to be false.

Coincidentally, at that moment TF 11 was steaming toward Rabaul. During this time the Lexington’s VF-3 had been reduced to just 16 F4Fs available for operations.

On the morning of February 20, TF 11 was on a northwesterly course north of the Solomons. The group was to swing southwest for the final approach to a launch point at daybreak the next morning. At dawn on the 20th, the Lexington launched six Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers on a search out to 300 miles ahead of the task force. The task force’s air defenses were reinforced by other SBDs acting as a low-level antisubmarine patrol.

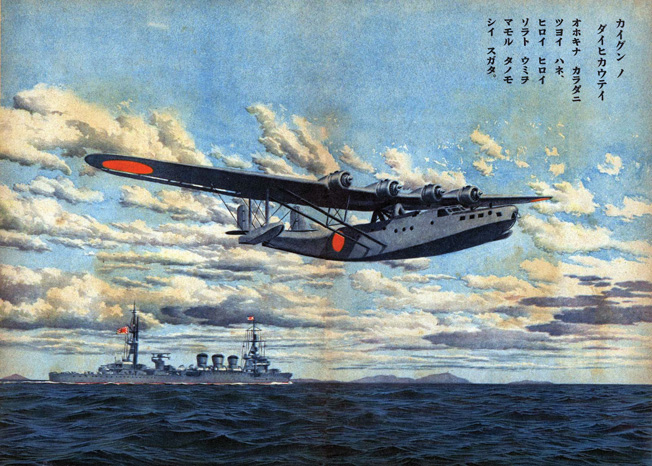

Spotted by Mavis Aircraft

The Lady Lex was outfitted with CXAM radar with a range of 80 miles under optimal conditions but unable to delineate altitude or numbers of aircraft. At 10:15 am, the radar detected an intruder bearing 180 degrees at 35 miles. Thach’s 1st Division of VF-3 was scrambled.

That morning, three four-engine Kawanishi Type 97 (“Mavis”) flying boats had departed Rabaul. The Mavis was a huge patrol aircraft with a crew of nine, a wingspan of 131 feet, a range of 4,112 miles, and armament including four machine guns and a 20mm cannon. The Kawanishis were dispatched to search an arc of 075 to 155 degrees to a range out to 500 miles.

At 10:30, Lieutenant Sakai Noboru, pilot of the flying boat covering an arc from 075 to 090 degrees from Rabaul, reported spotting an enemy strike force bearing 075 degrees and 460 miles from Rabaul on a course of 315 degrees. Noboru shadowed the task force, taking advantage of cloud cover.

Just before 11 am, Thach and his wingman, Ensign Edward R. Sellstrom, Jr., cruising at 12,000 feet, spotted the Mavis and accelerated to intercept, entering a rain squall in the process. Suddenly, the huge flying boat appeared just below Thach—as he described it, “right into my lap.” As Thach came out of the clouds, the Mavis had disappeared. The crew of the flying boat had apparently spotted the Wildcats and taken evasive action.

After a few minutes, the F4F pilots saw the Kawanishi break into the clear at about 1,000 feet off the water. Thach and Sellstrom went into a dive, approaching the flying boat from aft. Thach opted to make a high-side attack; Sellstrom crossed to the opposite side––standard tactics used to box in a target. On his run, Thach went after the starboard engines as Sellstrom started crossing behind the flying boat.

The Mavis’s tail gunner fired his 20mm cannon, causing Sellstrom to take action to avoid the shells as Thach dived in again from the right. On this pass an entire wing of the flying boat burst into flames. The Mavis skidded into the sea, followed by a tremendous fire and explosion. At 11:12, those aboard the Lexington spotted the black smoke from the crashed aircraft.

Thach and Sellstrom had barely returned to the carrier when radar picked up a second bogey––another Kawanishi Type 97, piloted by Warrant Officer Hayashi Kiyoshi, which departed Rabaul at 8:00 to cover an arc of 090 to 105 degrees. While en route, Kiyoshi had received orders to “amplify” the contact made by Noboru.

Lieutenant (j.g.) Burt Stanley and his wingman, Ensign Lee Haynes, intercepted Kiyoshi’s flying boat. During their attack, Stanley set the inboard port side engine on fire; flames spread to the fuselage. Haynes quickly followed Stanley’s lead. The nose of the Mavis dipped lower until it was diving out of control, trailing smoke. It crashed in a great ball of smoke and fire. The time of the kill was recorded as 12:18 pm. Kiyoshi had been unable to contact Rabaul.

The Japanese Attack

But the Japanese now knew the location of the Lexington’s task force. The ships of TF 11 were running low on fuel—there was no reserve for high-speed operations if a fight should turn into a running battle. So it was decided to call off the Rabaul strike. Instead, a feint was planned. TF 11 changed course to the southeast until late that afternoon. The hope was that even if the task force did not carry out an attack, it might divert Japanese attention from the East Indies.

At Rabaul, Admiral Eiji Goto, commanding the 24th Air Flotilla, was certain that once Lexington’s task force got within 200 miles of Rabaul it would launch a strike. To forestall that attack and beat the Americans to the punch, he would attack first at a range of 400 miles, well before Lexington reached its launch point.

To carry out such a mission he had available 18 Mitsubishi G4M1 (Betty) bombers of his 4th Air Group. Supplies of aerial torpedoes had not been received, and the available Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters did not have sufficient range to provide an escort. The lack of torpedoes would be unfortunate; the lack of a fighter escort would prove fatal.

The 4th Air Group, manned by veteran crews, included two divisions (chutais) of nine aircraft each, operating relatively new G4M1s manned by a crew of seven. Aircraft armament included four 7.7mm Lewis machine guns, one each in the nose, dorsal blister, and both beam blisters, and a 20mm cannon in the tail. Each aircraft could carry a payload of two 1,102-pound bombs. But the aircraft had no armor or self-sealing fuel tanks—critical shortcomings.

Mission leader was Lt. Cmdr. Ito Takuzo, who took the co-pilot’s seat in the G4M1 piloted by Warrant Officer Chuto Watanabe. Takuzo was a respected and experienced aviator, group leader of the 1st Chutai. One of the bombers failed to take off due to mechanical problems, reducing the strike force to 17 aircraft.

The 2nd Chutai of nine bombers was led by division leader Lieutenant Masayoshi Nakagawa. His 17 bombers followed 20 minutes behind a Kawanishi flying boat under Reserve Ensign Makino Motohiro, dispatched to help pinpoint the position of the American task force.

Bogeys on the Radar

At 12:40 pm, American radar picked up a bogey 80 miles to the west of the Lexington. At 1:17 pm, the target disappeared from the radar screen. During this time Thach’s 1st Division remained aloft until around 1:30. At the same time, a dozen SBD dive bombers were sent to scout in advance of the task force, and Thach’s aircraft were replaced by six F4Fs under Lt. Cmdr. Lovelace. In an effort to keep a CAP (combat air patrol) in the air with sufficient fuel, it was decided to make preparations to launch Lexington’s third division ahead of schedule.

At 3:42, a radar contact was made at a bearing of 270 degrees, 76 miles distance. Eighteen minutes later it was decided to rotate the CAP early in order to put fighters on station with full fuel tanks. A strike from Rabaul was expected. Fifteen minutes later, Gayler’s division of Wildcats began to launch.

At 4:11, a large blip was picked up at 255 degrees, 75 miles away; 20 minutes later, when the bogeys were 24 miles from the carrier, Gayler’s six F4Fs were vectored to intercept. In moments Gayler spotted nine green and tan twin-engine bombers formed tightly into a vee-of-vees. This was the nine aircraft of Nakagawa’s 2nd Chutai. Heavy clouds and rain squalls had compelled Lt. Cmdr. Takuzo to split his strike force into two elements, each to search independently for the American carrier. Nakagawa spotted TF 11 first, providing a contact report at 4:35.

Lieutenant Gayler and his wingman, Ensign Dale W. Peterson, prepared to attack from 13,000 feet. The Japanese bombers were at 11,500 feet flying at about 170 knots.

In the meantime, Lovelace’s division was kept aloft while Thach’s Wildcats, on Lexington’s flight deck, were hurriedly prepared for launch.

A Failed Bombing Run

Gayler and Peterson made the initial contact with Nakagawa’s G4Ms. At 4:40, the F4Fs sent the first of the Bettys down after a high-side pass. Using the speed they gained in their dives, the two fighters climbed to regain position for a second attack. Next to arrive were Lt. (j.g.) Rolla S. Lemmon and his wingman, Lt. (j.g.) Howard F. “Spud” Clark, and with a high-side run they shot down another Japanese bomber.

The third section showed up next, and one of its pilots, Ensign Willard (Bill) Eder, latched onto another bomber. But Eder was unable to climb above the enemy before they were upon him. He charged in from below and behind one of the trailing bombers and fired a long burst, but then three of his guns stopped functioning.

Meanwhile, Gayler was attacking the same target from above on his second pass, his gunnery deadly. In two minutes, the 4th Air Group had lost three bombers from its 2nd Chutai, and the surviving Japanese pilots tightened their formation to fill the gaps. The remaining six Bettys then emerged from a cloud within sight of the Lexington. Captain Sherman turned the carrier into the wind to launch Thach’s Wildcats.

At 4:43, another G4M, evidently the lead plane flown by Nakagawa, went down under the guns of Gayler’s wingman, Ensign Peterson, just as the cruisers and destroyers of the task force unleashed a barrage of antiaircraft fire.

The loss of the chutai’s lead aircraft with the master bombardier seemed to confuse the other crews momentarily. In level bombing runs the Japanese crews were trained to release their bombs simultaneously on command in order to bracket the target, but this time the bombers appeared to hesitate in their approach.

After regrouping, they moved to parallel the Lexington’s course, overtaking her from astern. As they did, another Betty was shot down by Lieutenant Lemmon, flying with Gayler’s division. The remaining four Bettys dropped their bombs, but the nearest detonation was 3,000 yards away––over a mile and a half––from the carrier.

100% Casualties for the 2nd Chutai

The Japanese bombers now turned for home, the Bettys accelerating to over 200 knots. As Lt. Cmdr. Lovelace managed to put a fatal stream of rounds in one of the enemy aircraft, he saw its 20mm tail cannon knock down Lieutenant (j.g.) Howard Johnson. Johnson managed to bail out and was rescued by a destroyer. Coming around to make a second pass at one of the bombers, Lovelace closed from below and behind, unleashing a burst of .50-caliber slugs.

Thach’s division was now back in the air, four of the Wildcats going full throttle after the retreating Bettys. Thach and Sellstrom hurried to overtake the fleeing bombers; Thach reached a point just above and ahead of a bomber and turned to make a flat-side approach. As he did, Thach saw an F4F approach from dead astern of the target, then a 20mm shell fired from the tail cannon of the Betty exploded in the windshield of the Wildcat, claiming Ensign John (Jack) Wilson, who was killed instantly.

Thach followed through on his flat-side approach, hitting the Betty in the engine and wingroot and causing it to catch fire. Recovering from his run, Thach found himself behind and beneath another bomber. He zoomed up for a high-side run and put several well-placed rounds into one of the engines, causing an explosion and the wing to fall off. This was one of Thach’s two kills that he shared with a 2nd Division pilot who was attacking the same target.

By now eight Bettys had been either shot down or forced out of formation, and Thach soon dispatched another, concentrating his fire on its port engine, which exploded taking off the wing.

At the same time, an SBD Dauntless flown by Lieutenant Edward H. Allen, part of Scouting Two, came upon a crippled bomber that had managed to arrest its descent; Allen finished it off with his .30-caliber machine guns. He then caught up with a second damaged Betty and maneuvered his SBD so that his rear gunner, ARM1c Bruce Roundtree, could blast the bomber. The enemy bomber began to burn rapidly and fell into the sea.

Another badly shot-up and flaming Betty in the process of trying to escape encountered Lieutenant Walter Henry of Bombing Two (VB-2) as he was returning from patrol. Henry was able to turn onto the bomber’s tail, and one short burst from his twin .30s was sufficient; the G4M pitched over and crashed. The 2nd Chutai, all nine aircraft, had been wiped out.

Two Wildcats Left

Meanwhile, accompanying the eight bombers of the 1st Chutai, Lt. Cmdr. Takuzo had monitored Nakagawa’s message on the Lexington’s position. He was north of the enemy’s reported location and turned south in search of the task force. At 5 pm, Takuzo radioed Rabaul that he had the enemy in view and was about to attack.

Cruising at around 15,000 feet and anticipating the bomb run, Takuzo began descending to 11,000 feet. In the process, the bombers accelerated to about 190 knots. When he first spotted the American carrier to the southwest, Takuzo planned to parallel the target’s course and overtake it from astern. Because most of the American fighters were busy knocking down Bettys of the first wave as it withdrew, only two Grummans lay between Takuzo and his target.

The eight Bettys headed for the Lexington while maintaining a disciplined formation. In reserve above the carrier was Lieutenant Edward (“Butch”) O’Hare and his wingman, Lieutenant (j.g.) Marion Dufilho. The pair raced eastward to intercept and arrived 1,500 feet above the Bettys at 5 pm. The situation approached a crisis as seven F4Fs were off to the west pursuing the first wave while Lovelace’s five F4Fs from the 2nd Division, almost out of fuel, circled at low altitude around the Lexington awaiting the go-ahead to land.

The Japanese bombers came on in two three-plane vees with two more planes backing up the port vee. O’Hare and Dufilho engaged them at 5:05, three miles astern of the Lexington. The pair allowed the Bettys to pass beneath them, then rolled onto the right-hand vee and pushed their throttles forward.

O’Hare Alone Against the Bettys

Dufilho’s guns jammed, leaving only O’Hare to engage the Japanese aircraft. The bombers held a tight formation as they had been trained in order to provide mutual defense and for bombing accuracy. O’Hare’s Wildcat was armed with four .50-caliber guns with 450 rounds per gun––enough ammunition for about 34 seconds of sustained fire.

O’Hare’s initial maneuver was a high-side diving attack using deflection shots. He placed bursts into a Betty’s starboard engine and wing fuel tanks; when the stricken craft of Petty Officer 2nd Class (PO2c) Baba Tokiharu on the right side of the formation abruptly lurched to starboard, an engine began smoking heavily.

O’Hare then ducked to the other side of the vee formation and aimed at the enemy bomber of PO1c Mori Bin on the extreme left. A few well-directed short bursts hit Bin’s right engine and punctured the left wing tank. Trailing a thin, white stream of fuel, the bomber shuddered as its speed dropped abruptly, then wheeled to the right and out of the formation.

Bin’s bomber had not sustained fatal damage, but did not regain formation. After jettisoning his bombload, Bin withdrew at low altitude. Having extended his high-side run to shoot at the second target, O’Hare crossed over to the left side of the Japanese formation, where he moved to regain position.

Starting his run from the left side of the formation, O’Hare set about dealing one by one with the three aircraft in echelon on that side. With a shallow high-side run, he fired into the rear aircraft, aiming at the port engine nacelle; he fired until he saw flames from the aircraft.

O’Hare had to change course slightly as the first target in his path, PO1c Maeda Koji, skidded violently in mid-air; then he charged after the next aircraft in line, PO1c Uchiyama Susumu’s bomber, flying behind Takuzo’s left wing. O’Hare fired into the bomber’s left wing and engine and watched as the engine flamed up and seized, causing the Betty to veer sharply left into a dive. Five bombers were still in formation.

The surviving Bettys managed to drop their ordnance, their bombs landing astern of the wildly maneuvering Lexington. Though one was as close as 100 feet, all 10 bombs missed.

O’Hare had not yet finished; his next target was the lead bomber. Closing to point-blank range, his slugs tore into Takuzo’s port nacelle, which flared up and exploded. The engine then wrenched free of its mounts and dropped away.

Trailing thick, black smoke the aircraft careened sharply to the left and started down. Even with the engine gone, the pilot struggled at the aircraft’s controls in an attempt to crash his plane into the Lexington, but the plane plunged into the sea in a fiery explosion about 1,500 yards ahead of the carrier’s port bow. The Lexington turned sharply to avoid running over the blazing pyre of fuel and debris.

The 1st Chutai’s surviving aviators, heading away at high speed, interpreted what they saw as their commander’s plane crashing into the carrier—considered a noble death.

Hit by Only One Bullet

After dropping their bomb-loads, the remaining 1st Chutai planes had to run the gauntlet of seven F4Fs and several SBDs. Holding formation were the four bombers of Lieutenant (j.g.) Mitani Akira and Petty Officers Maeda Koji, Ono Kosuke, and Kogiku Ryosuke. Far beneath them limped PO1c Bin’s battered aircraft, forced out of formation on O’Hare’s first pass.

Akira’s aircraft did not make it out of the target area. Ensign Sellstrom caught him and shot him out of the sky; some of the surviving Japanese crewmen reported that Akira had crashed into an American ship. This left three bombers in formation, with Bin flying alone. Forty miles out, Lieutenant Gayler tagged another bomber and claimed its destruction.

About 30 miles from TF 11, Lieutenant Allen and his gunner, Roundtree, of Scouting Two, latched onto the remnants of the retreating bomber formation, resulting in a long chase. Allen’s SBD had only a slight speed advantage of about three knots.

He selected one Japanese bomber and eased into firing range, allowing Roundtree to use his .30-caliber machine gun from his position in the rear of the aircraft. Allen homed in on the aircraft flown by PO1c Ono Kosuke; Gunner Roundtree shot up the starboard engine and killed at least two of the crew. Kosuke would not make it back to base.

After chasing the bombers for 150 miles, Allen saw he was running low on fuel, broke off his pursuit, and turned for the Lexington.

The Navy fighter squadron on that day claimed 15 twin-engine bombers and two four-engine flying boats destroyed, along with a 16th bomber falling to Lieutenant Henry of Bombing Two. Fifteen American pilots of VF-3 claimed hits on enemy aircraft with multiple shared shootdowns. American losses totaled two Wildcats—one pilot missing and another wounded.

O’Hare believed that he had shot down five bombers and damaged a sixth—all in just four minutes. Lt. Cmdr. Thach later reported that at one point he saw three of the enemy bombers falling in flames at the same time.

With his ammunition expended, O’Hare returned to the Lexington. O’Hare’s fighter had been hit by only one bullet during the fight––the single bullet hole in the port wing disabling the airspeed indicator.

Thach calculated that O’Hare had used only 60 rounds of ammunition for each bomber he destroyed. In the opinion of Admiral Wilson Brown, Jr., commander of TF 11, and of Captain Sherman, commanding the Lexington, Lieutenant O’Hare’s actions may have saved the carrier from serious damage or even loss.

In fact, O’Hare had destroyed only three Bettys: PO2c Baba’s, PO1c Uchiyama’s (flying at left wing of the leading vee), and the leader of the formation, Lt. Cmdr. Takuzo’s. Another two had been damaged—PO1c Koji (left wing of the vee) safely landed at Vunakanau airdrome and PO1c Bin was later shot down by Lieutenant Gayler when trying to escape, about 40 miles from the Lexington. For his actions, though, Lieutenant Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor. America needed heroes, and O’Hare became one of the first. (See WWII Quarterly, Winter 2016.)

A Momentary Strategic Victory

At Rabaul, the 24th Air Flotilla headquarters, at 6:15 pm, a 1st Chutai crew radioed that the bombing attack had sunk one enemy warship. The communications indicated that the task force’s defenses were highly effective, resulting in the loss of several Japanese planes.

At 7:25, PO1c Kosuke ditched his badly damaged Betty east of New Ireland at Nugava in the Nuguria group. Some 25 minutes later (7:50 pm), PO1c Koji and PO2c Ryosuke reached Rabaul and landed safely. Riddled with holes, the aircraft were not operational for several days.

The 4th Air Group had lost three senior officers and 13 crews along with 15 bombers. The survivors claimed to have sunk one cruiser or destroyer and set the American carrier on fire, while also downing eight fighters. In actuality, they had shot down just two F4Fs and not hit a single ship. The Japanese high command believed that their losses were the price to be paid for an unescorted attack on American warships.

More Bettys would be lost before the Japanese command started to consider the bomber’s vulnerabilities. Further, the Japanese attack had revealed several problems. The Betty medium bomber had no armor, no self-sealing fuel tanks, and little armament for defense except the 20mm cannon in the tail. Also, operations were planned with little imagination; the bombers held rigid attack formation during strikes, which made them ideal targets.

The Japanese command postponed the impending invasion of Lae and Salamaua from March 3 to March 8 due primarily to the presence of the Lexington. Thus the U.S. Navy aviators had achieved a strategic impact on operations in the Southwest Pacific for the moment.

Errors of Task Force 11

Mistakes had been made by the Americans as well. The fighters had pursued the first wave of bombers far from the ships they were intended to protect and should have re-grouped sooner. Both F4Fs that had been shot down were lost while making zero-deflection runs from directly astern of the targets; the most effective attacks were overheads and high-sides.

The Grummans had also suffered from jamming of their machine guns and a low climb rate. Antiaircraft fire from the ships had impacted operations, as the fighters had been told that the ships would hold off until the last moment if the fighters were scoring well. Instead, the antiaircraft gun crews had opened too early, the fighters having to fly through their fire.

The lack of IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) had made it difficult to sort out the CAP, search planes, and the hastily launched antisubmarine patrol. But Lt. Cmdr. Thach stressed that the battle had proved their tactics, along with expert marksmanship and teamwork. The Americans also recognized that the Japanese attacks had been carried out with determination.

Because it was so difficult to surprise the Japanese at Rabaul, the Americans would not attempt another such raid until reinforced by additional carrier forces. Later the carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5) and TF 17 sailed into the South Pacific to join the Lexington in an effort to blunt Japanese operations.

The “Thach Wave” and the “Big Blue Blanket”

The Lady Lex would be sunk just three months later, May 8, during the Battle of the Coral Sea, after being struck by two torpedoes and two bombs, and Butch O’Hare would be lost while leading nighttime operations on November 26, 1943. John Thach developed the “Thach Weave,” an aerial combat tactic for dealing with enemy fighters of superior performance, and later the ”Big Blue Blanket”—saturation flights of combat air patrols to deal with kamikazes. He would go on to retire from the Navy as a full admiral.

There would be much hard combat ahead in the Pacific—on land, on sea, and in the air. The Lexington’s pilots, just two months after the disaster at Pearl Harbor, proved that they were at least as good as anything the Japanese could throw at them. And their superb showing in the skies above the Solomons was a precursor of victories to come.

I am under the impression that the air unit encountered by the Lexington had many of the same planes and crew that attacked and sunk the Prince Of Wales and Repulse only two months earlier. This was a very different result with profound implications for Japan’s attritional island defense strategy, that was largely built on wearing down the advancing American fleet with aerial torpedo strikes.