By Bob Bergin

Major General John K. Singlaub was a young airborne lieutenant when he took up an offer from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to become engaged in “hazardous duty behind enemy lines.” He was a participant in Operation Jedburgh and parachuted into occupied France to organize, train, and lead a French Resistance unit. When the Germans were driven from his operational area, he was concerned that he might miss the rest of the war and volunteered for duty in the Far East. He was sent to China, where he trained a guerrilla unit to operate in Japanese-occupied Indochina and just before the Japanese surrender led a dangerous mission to rescue allied POWs on Hainan Island off the Chinese coast. The operations carried out by General Singlaub and other OSS Special Operations officers during World War II were the foundation upon which the U.S. Special Forces were built and the basis for the special operations that are conducted by U.S. forces to this day.

Sitting Down with Major General John Singlaub

BOB BERGIN: At the time of Pearl Harbor you were in ROTC at UCLA. Could you tell us about your interest in a military career?

JOHN SINGLAUB: I joined junior ROTC at Van Nuys High School in 1937. When I turned 17, I enlisted in the reserves. I wanted to be an infantry officer. I applied for an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy, but my congressman turned me down. He said he couldn’t do it for the son of a Democrat, a very conservative Democrat, I might add. I decided I would go to UCLA and get a reserve commission. I was commissioned in January 1943 and went straight to parachute school. I was serving in a parachute regiment at Fort Benning when an OSS recruiter came to review officers’ records. Those with a language qualification were asked if they were interested in joining an organization that engaged in hazardous duty behind enemy lines. I was on a TDY (temporary duty assignment), and when I came back the adjutant asked if I was interested. I thought I was already in a unit preparing for hazardous duty, but OSS sounded interesting. I was pleased to learn that the language they were interested in was my French, not my Japanese. I had studied both at UCLA.

BB: You came to Washington in October 1943?

JS: I had orders to report to the Munitions Building at 17th and Constitution in Washington, a temporary building from World War I that was still in use. There I was told to report with my kit the next morning to the parking lot at ‘Q’ Building down the street. Others showed up, and we were loaded into the back of a two-and-a-half-ton truck. They put down a flap so we couldn’t see out. One of the guys asked where we were going. The driver said, “The Congressional Country Club.” Ask a dumb question, we thought, and you get a dumb answer.

Well, we did go to the Congressional Country Club over in Maryland. OSS did some training there, but for us it was mostly psychological assessment. They put us in training exercises where we acted as squad leaders and were presented with problems. One guy would always mess things up. He looked like a fellow student, but in fact was a member of the faculty. He was there to see how we handled the problems he caused.

BB: How long were you there?

JS: Less than a week. We went farther into Maryland, to a former boys’ camp that President Roosevelt called Shangri-La; today it is known as Camp David. It was taken over by OSS, and we did some serious training there. Our principal instructor for weapons training and hand-to-hand combat was Major William Fairbairn, a well-known British Army officer. He had been the head of the British Police in Shanghai when he was drafted by the British Army. [Fairbairn was legendary for creating his own deadly form of hand-to-hand combat and for designing the famous Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife with Major Bill Sykes, who was also a close-combat instructor for OSS officers in England.]

BB: How did Fairbairn become part of OSS training?

JS: President Roosevelt had authorized William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who later conceived and organized the OSS, to go to Great Britain in 1940 to look into things like espionage that we didn’t know very much about. Donovan came back and tried to introduce the American leadership to what he called “the fourth dimension of warfare.” The first and second dimensions were land and naval warfare; the third, air warfare, was introduced in World War I. The fourth dimension, Donovan said, was to organize the enemy’s rear areas to our advantage. The idea was to help people under German occupation and use them to achieve our objectives. It’s what my group was heading for. We had been recruited for a joint British-American effort, and the Brits set up the schooling. Most of our training took place in Great Britain. When we arrived there, we were met by a British Army officer, and from then on were under British command. The commanders of the training areas were Brits; the curriculums were organized by British Special Operations Executive (SOE) officers. We had a joint OSS-SOE HQS in downtown London.

BB: Where did you train in Britain?

JS: Initially, in Scotland, where we arrived in December 1943. In January 1944, we moved to southern England, and in April to our final training site at Milton Hall near Peterborough. The plan was for the United States to provide 50 officers and 50 enlisted radio operators. In fact, I think we had 47 officers and about same number of radio operators.

BB: This was the Jedburgh Operation? [Jedburgh was also a Scottish border town renowned for its fierce warriors].

JS: We were Jedburghs. Each of our teams consisted of three men: one English-speaking officer, British or American; a second officer from the country we would operate in; and an enlisted radio operator. The foreign officers were mostly French, although we had a couple of Belgians and about four Dutchmen. The training we received from the Brits was outstanding, particularly in weapons and demolition. They had learned a lot from conducting clandestine operations while running their colonies. That gave them a lot of experience we didn’t have.

BB: You were a qualified paratrooper, but now you were jumping with the British, who did things differently?

JS: Airborne qualified or not, everyone was sent to the parachute school for the British Airborne forces. They ran a special pre-jump course in their parachute landing training, which was far superior to ours. I was always thankful for that. It was years before the Americans used the parachute landing fall (PLF) devised by the Brits. And their parachutes were different—they were bag packed—the bag with the parachute inside stayed at the end of the static line until the suspension lines were fully extended as you fell away from the airplane. Then the silk canopy broke out of the bag. That greatly reduced the number of canopy malfunctions. The majority of jump aircraft in the British system were bombers. They took the belly turret out and lined the opening with wood. That’s where we exited.

BB: That was what they called the “Joe hole”?

JS: The RAF never referred to us as agents or people or humans. Each of us was “just another Joe.” They also used barrage balloons with a basket attached, sent it up 800 feet. The advantage was that you knew where the balloon was, even if you couldn’t see anything. We jumped in very thick fog, and at night. We did two balloon jumps for every one from an aircraft. It was cheaper that way. We had to learn to have confidence in the British system. The Brits jumped without a reserve. At some of the altitudes we jumped, there was no time to use a reserve.

BB: How were your teams formed? Was it a self-selection process?

JS: It could be. A French officer and a Brit or an American became friends and then teamed up. But psychological assessments were a big part of the process. The man who ran psychological assessments for the OSS at the Congressional Country Club provided input. We were training in southern England at a place called Milton Hall when the teams were announced. I was very satisfied. My radio operator was a sergeant named Tony Denneau, from Green Bay, Wisconsin. He stayed with me for most of the war. The French officer’s real name was Jacques de Penguilly. He’s still alive in Brittany. His nom de guerre was Dominique Leb. The three of us got along great. We spent all our time together, trying to reinforce each other’s skills.

BB: Wasn’t it around this time that you met your case officer?

JS: There was a guy apparently in charge, Bill Casey. He came out to the airfield where we were held in isolation. He checked us out, gave us our final briefing, and offered us L-tablets [suicide pills] that we could use if we were captured.

BB: That was Bill Casey, who later became Director of the CIA. What did you make of him then?

JS: He was a Navy lieutenant, but came in civilian clothes. He was slow speaking, but smart and really knowledgeable about what was happening in France. He was a New York lawyer when Donovan brought him in. Donovan did a lot of his own recruiting. For his staff, he liked people who were compatible, whose capabilities he knew. A lot of them had zero military background, but they had other skills he wanted. He recruited from all walks of life, academics, museum administrators, lawyers, other parts of the government. Donovan had a personality that made people want to go with him and see what he had in mind.

BB: Did you accept the L-tablets Casey offered in case you were captured?

JS: I refused. I said I didn’t intend to be captured. I didn’t want anyone to consider surrender as an acceptable option. I got this point across to my partners, who agreed.

BB: It was spring 1944, and you must have had a feeling the invasion was coming.

JS: Everybody had that feeling. But I also was having painful attacks in my abdomen and eventually went to the medics. It was appendicitis and had to be operated on. What made me really sick was the idea that I would be out of action. Fortunately, they put me in an American hospital. The U.S. colonel who did the operation was an expert and said I would be ready to jump in a couple of weeks. The British doctor said he had never heard such nonsense; it would be a couple of months at least. I was ready to be released from the hospital when D-Day occurred. I was absolutely crushed. I had missed the whole thing. Then my two partners, Jacques and Tony, came to the hospital and said they would wait for me. Our mission had been changed. We were originally going to go into Brittany because my Frenchman was from Brittany.

As it turned out, none of the Jedburgh teams went in before D-Day. It was a matter of operational security. Some of Eisenhower’s staff were simply not up to date on airborne operations. They were veterans of World War I. They didn’t know that the British and the French had been parachuting agents into Europe and that most survived. The staff finally brought in advisers, but the process delayed the dispatch of the Jedburgh teams. My mission was changed from supporting the Normandy invasion to supporting the coming southern invasion.

BB: You were to link up with the French Resistance in Central France, train them, and set up drops for weapons and other supplies. Who were the French you would work with?

JS: We had two groups to deal with. One was the AS, the “Armee Secrete,” that was led primarily by French regular officers who had refused to evacuate to North Africa. They were reliable, knowledgeable, and could handle most of their own training. All they needed was supplies. The other group was the FTP, the “Franc Tireurs et Partisans.” They were the Communists, led by members of the Communist Party. They swore they were loyal to de Gaulle, but they didn’t always follow his instructions from London. We learned later that they got instructions via the Soviet Embassy in Berne, Switzerland. There were real French patriots among them, men who did great things. But the FTP wanted to stay in the towns. It gave them a great political advantage in the years that followed the war.

BB: Tell us about your jump into France on August 11, 1944.

JS: Our drop aircraft was a Stirling bomber from a special squadron. We took off from England, rendezvoused with the bomber stream, and started out on the night mission. At the limit of our fighter escort, our pilots faked an abort. They turned back toward England and dropped below German radar. A French Special Air Service (SAS) team had been put on our aircraft at the last minute. They jumped before we did. Their drop was not good; they were kilometers from where they should have been. Our drop was right on. As we neared the DZ [drop zone], fires were lit below, three fires in line with our direction of flight, and a light alongside that flashed the Morse code letters for that night’s drop.

The jump itself was uneventful. At the DZ we were met by an SOE agent named Simon. He was British, but born and raised in France. His job was to collect intelligence to determine the resistance potential in the area. He had established good agent nets and found that the resistance was already partially organized. All they needed was advisers, trainers, and contact with supply.

Simon introduced us to Hubert, the AS leader, and then disappeared. Hubert hustled us off the DZ and into a barn. We slept there, and in the morning the farmer’s daughter brought us a fresh mushroom omelet, a real treat. We had not had real eggs all the time we were in England, where the ration for a soldier was one egg a week. All we ever got there was powdered eggs.

BB: How close was the nearest concentration of Germans?

JS: About 20 kilometers away, in the town of Egletons, which quickly became the focus of our attention. It looked as though the Germans there were getting ready to fight. They moved from their garrisons in the downtown area to the outskirts, to a school on a little hill. The school building was reinforced concrete and stone, a very rugged thing, and it had clear fields of fire all around. It was an excellent spot for the Germans and a real problem for us.

BB: Dealing with the two different resistance groups must have been interesting.

JS: We found that we could not rely on the FTP to hold a sector or attack when they were told to. We got word via coded

BBC broadcasts that we would be authorized to attack the local German garrisons in a couple of days. To us it was simple: the directions came from London and we would not attack until the day we were told to, but the FTP started their attack at Egletons a day early. Our concern was an anti-Maquis force to the east, at Clermont-Ferrand, about 50 kilometers away. They had armored cars and trucks, light mortars, and a lot of machine guns. We knew that if the thing went on too long this force would come to relieve the siege.

What the Germans did not know was that the other three German garrisons in our area were put under siege and agreed to surrender. The Germans at the villages of Brive and Tulle insisted on surrendering to an American. As I was the only American around, Hubert drove me there in his car. I took their surrender, and then we drove back to Egletons.

BB: How strong was the German force in Egletons?

JS: As near as we could tell, there were between 150 and 200, including elements of the Das Reich panzer division. They were well armed and had antitank guns and a radio that gave them an advantage the three other garrisons didn’t have. The others had to use telephones. The telephone exchanges were all manned by the resistance, and we were able to keep track of what they were up to. When we put those garrisons under siege, we just unplugged them.

BB: From what I read, you found yourself right in the middle of the action in Egletons.

JS: I was trying to do a reconnaissance of the area and got into this house. It was two stories and had an attic from where I could get a good look into the area around the school. I spotted an antitank gun that I first saw that morning when it put a round through the roof just as I exited the attic. At this particular time I wasn’t remembering everything I was taught. As I moved around the attic, I put myself between the hole where that round came in and the hole where it went out. I must have blocked the light. The gunners saw that and decided to do something about it. I saw them moving the gun my way, and scampered down the ladder just as a round went through the area I vacated.

A sniper was shooting at me, and fragments from the slate roof hit my face and tore up my right ear. I was bleeding like a stuck pig. Some of the FTP troops were sitting around the yard as I came out. They were shocked by my appearance. I grabbed one of their Bren guns and an extra magazine and worked my way down the street without being seen. I got behind some bushes from where I could get a good look at where the gun was. It was camouflaged, but I fired a full magazine at it. I could see I hit some of the Germans. I slipped in another magazine and waited. When they tried to man the gun again, I opened up with the Bren. That put them out of action. We didn’t hear from that gun again.

BB: Did this make any impression on the FTP troops sitting in the yard?

JS: They didn’t have much of an appreciation of what you do in a war. They were not trained and did not want to be. When they saw what our team was willing to do, that an American was willing to risk his life, it did make an impression on them. I told them we wanted to help, but we didn’t want to do their work.

BB: How did the situation evolve after that?

JS: The French SAS team arrived. There were about 24 of them, trained by the British SAS and very good. They had a British two-inch mortar, comparable to our 60mm, but very few rounds. We wanted to get the Germans out of the top floor of the four-story school building from where they dominated the whole area. I told the SAS I would act as their observer. We fired into the roof and set it on fire. When it burned out, the Germans were completely exposed. That really reduced their effectiveness.

BB: I recall from your book, Hazardous Duty, that you were attacked by German aircraft at Egletons.

JS: We were hit first by Heinkel He-111 bombers. They came in very low, probably because they were looking for us. They dropped butterfly bombs, antipersonnel bomblets that spun as they fell and threw the pin that held the striker. Then they sat there and exploded if somebody bumped them It was demoralizing. The ordinary 100-kilo bomb was less terrifying. You could see it coming. When it landed, it exploded and the killing was done. But those damn bomblets lay in the grass, and you couldn’t go stumbling around in a place that was booby-trapped by those damn bombs.

BB: Your men got a Heinkel with Bren guns?

JS: It came in so low it was easy. I could almost see the hits. The pilot turned away to the southwest. The plane wobbled, but looked under control. Later we learned it crashed. We were subjected to a lot more attacks by fighter bombers, [Focke Wulf] Fw-190s. They dropped single bombs and strafed us. I finally requested air support, and in return got some wise comments from OSS London. Later, I accused Bill Casey for that, but all he did was smile. The message we received said, “You’re getting more air attacks than the Invasion Force at Normandy.” And that was true. The Luftwaffe had been driven inland; we were closer to Germany than Normandy was. And we didn’t have any antiaircraft guns.

BB: How did the siege in Egletons finally end?

JS: The German anti-Maquis column arrived. We set ambushes on the road, but when it was clear that the Germans would break through, we took to the hills. Jacques worked with the SAS troops to ambush any Germans that tried to break through. Although the Germans at Brive and Tulle to the west had surrendered, the FTP now claimed that the Germans there had organized a force that was coming to attack us.

BB: Did the FTP have bad intelligence?

JS: The FTP did not like the idea that the AS was having success, and the rumors greatly weakened our ability to operate. We couldn’t get any of the FTP troops to man the ambush sites, so we made do with the AS forces, and they did a great job. The Germans got to Egletons, found some wounded, and took them. They planned to go to the west but ran into more AS ambushes, so they turned around and went back to Clermont-Ferrand.

BB: The Germans effectively had been cleared out of your area. Was your job done?

JS: We looked for a new mission. I didn’t recognize it then, but our whole area, the Department of Correze, and several other departments in the region were liberated without assistance from conventional forces. The Germans were now starting to move their forces on the Atlantic Wall back into Germany. They didn’t want to go through our area. They went farther to the north, but kept south of the Loire River. I got permission from London to take some of our AS troops up there to set up ambushes. We made sure they didn’t come down our way. We made it very unpopular to go through our area.

BB: How did you move your troops around the area?

JS: We used farm trucks, charcoal burners. A stove on back of the truck heated charcoal to make the gas that went into the engine. This was not conducive to making a fast getaway. We would drive to the ambush position with the trucks, leave them some distance off. Afterward, when the troops got back to the trucks, they had to crank up the fire before we could leave.

We prepared an old German airfield that had been bombed into uselessness. There were still delayed-action bombs on the runways that we had to deal with. Because we were beyond Lysander [transport aircraft] range, Hudson bombers had to be used as transports, and we arranged for one to come in. We had downed Allied airmen to send out. That was also one of our missions. Our area was a logical place to hide downed airmen until we could exfiltrate them.

BB: Eventually you left from that airfield.

JS: Jacques and I flew to London. We had some conferences about setting up a Jed base inside Austria. We had learned that there were a large number of French in Austria who had escaped from forced labor camps and been taken to the Tyrol mountains. The idea was to drop Jed teams in to organize them. The Brits and Americans signed off on the idea, but French Intelligence had say over the use of French Jeds. The French Service was now back in Paris, and Jacques was ordered to report there.

I flew back into France to pick up my team. We traveled by automobile across areas where the Germans were still on the move. We had been advised to try to get across the Loire River in the vicinity of Orleans, where American forces had pushed across the river. We found some American troops on the south bank, and they couldn’t imagine how we had come through this territory full of Germans.

BB: I recall reading that on your drives through German-occupied areas, you figured out the interval the Germans kept between convoys and then drove in the gap.

JS: The Germans were very methodical. Once you knew the interval between their convoys, you could cut the time in half and get on the road in between them. On one series of reconnaissance missions I was with “Popeye Revez,” the French Jedburgh team leader from the area next to ours. He was up front with the driver, and Jacques and I were in the back seat. Years later Popeye and Jacques would laugh about how—when we passed through a French village—I would greet the young ladies we saw. Jack was in the back seat shouting—in English yet—“Hi Tootsie!”

BB: It sounds almost like fun.

JS: It was not all bad; we had some pleasant times. There were still castles with families living in them, and sometimes we were invited in. They had bricked up their wine cellars, as did the people in the towns. The good wines were hidden where the Germans wouldn’t find them. We always had good wine, or somebody would uncork a 50-year-old cognac. When a town was declared cleared, the people wanted to share what they had been hoarding. Our primary diet was wine, big cheeses, and fresh bread. It certainly simplified our class one supply. There was stress, strain, and pain, but you could survive.

BB: What happened after you left France?

JS: Our team stayed together because of our potential mission to Austria. It was already agreed that Austria was going to be administered by the four [Allied] powers after the war, and each of the four had to be consulted to approve this operation. I finally told Jacques that I thought this would drag on and we’d miss the rest of the war. I volunteered to go to the Far East.

They gave me 30 days leave in the States, and I got married. I had briefings in Washington and some training on Catalina Island. I ended up as the leader of the OSS group. We boarded a troopship at San Pedro and embarked on a 35-day zigzag course to Calcutta via Melbourne and Perth. From Calcutta we went by train up toward the Himalayas to Dinjan, and by truck to Chabua. When I found it would be two weeks before we could fly over the Hump, I volunteered my unit to assist OSS Detachment 101 move its headquarters to Bhamo in Burma via the Ledo Road. Japanese stragglers and Chinese bandits were still setting ambushes on the road, and I spent the time scanning for places we might be ambushed. It was ironic. A few months earlier I was the one setting ambushes.

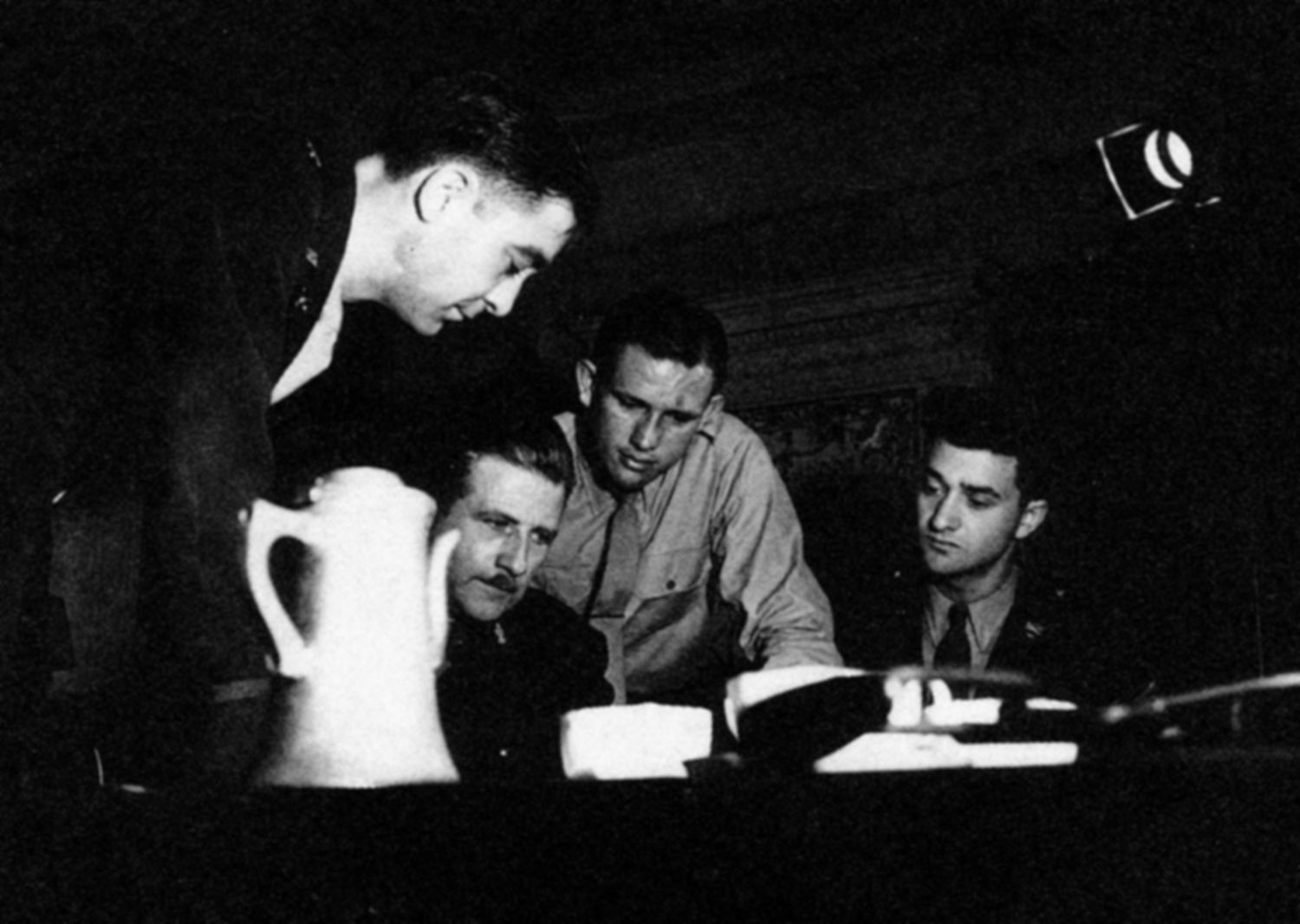

BB: What happened when you finally got to Kunming?

JS: I reported to the OSS commander, Colonel Richard Heppner, and our bunch was divided up. I was assigned to train a guerrilla unit of young Vietnamese at Poseh, our base camp near the Chinese border with French Indochina.

BB: Was this near Ho Chi Minh’s turf?

JS: We had an OSS team working with Ho Chi Minh. He felt he was in charge of all of Vietnam, and anything the Americans did there needed to be cleared with him. That caused problems. I didn’t realize it at the time, but my mission was delayed several times because of Ho. Later, I learned that Ho objected that I was being inserted into an area he did not consider strategically important. He wanted my team with him, where he could select targets and commit us where it would do the most good— for him. OSS headquarters also thought I should take a French officer along, which didn’t make sense to me. The French no longer had influence, and they weren’t supplying anything. They said it was their territory, but it was Japanese territory now. I didn’t take a French officer on my team.

BB: What was your mission?

JS: To jump into Vietnam with enough explosives to cut the road and the rail line that ran from the Hanoi delta through a gorge in the mountains to a border town called Lang Son. This was the route the 21st Japanese Division would take if it had to oppose a landing of American forces in China.

BB: Was a landing in China actually planned?

JS: A landing in China was part of a deception plan to hold local Japanese forces in China so they couldn’t be used against the main U.S. landings in Japan, which were planned for the island of Kyushu. The idea was that an American force would seize a beachhead in China that included a port. Having a port in China would take pressure off the long logistical trail that stretched all the way from Calcutta. This planning was not something we wanted to discuss with Ho Chi Minh. Because of that, Ho thought that the road I was going to cut was not heavily traveled. We couldn’t say it was lightly traveled now, and that’s why we wanted to cut it—so that it can’t be traveled when that Japanese division needs it.

The delays went on until the first A-bomb was dropped, and Kunming put my mission on hold. When the second A-bomb was dropped, our mission was cancelled and I was told to get to Kunming as soon as I could.

I got to Kunming in a heavy monsoon downpour. I went to sleep on an upper bunk and awoke to find a stream of water flowing through the barracks. My foot locker was afloat. The walls were made of clay brick, and they started to dissolve. I finally got to see Colonel Heppner in a dry office. He asked if I was willing to take a rescue mission to Hainan Island where the Japanese were holding a large number of Allied POWs. We had to take control of them. We had learned from intercepts that the Japanese commanders had been given instructions to kill all Allied POWs, and even how to do it most effectively.

BB: How did you prepare for the mission?

JS: I had a briefer, a Captain Woods from the Air Ground Aid Service, or AGAS, an intelligence unit that worked with Chennault’s Flying Tigers. His job was to prepare air crew for escape and evasion, and to know everything possible about the Japanese POW camps in China. He briefed me and gave me photos that I used to pick a DZ. Then he begged to go along. I made him our executive officer.

BB: You had to put together a new team?

JS: I picked people I needed. There were nine of us, and only five had jumped before. Tony Denneau volunteered to stay as my radio operator. From my team in Poseh, I had a medic and a Marine who I knew would be useful. I wanted Japanese and Chinese interpreters. My Japanese interpreter, Lieutenant Ralph Yempuku, was outstanding. He was a Nisei from Hawaii who had fought with OSS Detachment 101 in Burma. The mission was urgent, but the rains in Kunming continued. We had to collect our gear in a rubber boat.

BB: How did you get to Hainan?

JS: We left Kunming in a C-47 and flew across the upper part of Vietnam. At the Gulf of Tonkin, we got 50 feet off the water. We turned down the coast until I saw a small jetty that I recognized. I knew the camp was just inland from that. We turned out to sea, gained altitude, and started in. I wanted to drop at 600 feet, really the minimum. I showed the pilot where we were going, then went back to get at the head of the stick. I put a strong jumper behind the last of the nonjumpers and designated him the push master. We landed relatively safely. Our Japanese interpreter had his chin badly cut by the quick opening device on the parachute harness.

The Japanese thought we were attacking. A squad was on its way with fixed bayonets. We saw their trucks coming as we rounded up our supplies. Most of our equipment had been destroyed by being dropped too low. The parachutes were still deploying when they hit the ground, and the bundles just exploded. Our radio was all over the field. Not a great beginning.

I found another injury. My exec, Captain Woods, had been hit in the back of the head by a connector link and knocked silly. His job was to take photos. If things went sour, somebody might find the camera and that might explain what happened. There he was, staggering around, taking pictures, looking totally unconcerned about the weapons pointed at him. Then the medic came and said Captain Woods had a concussion.

BB: What happened when the Japanese got to the drop zone?

JS: The Japanese lieutenant and I had a confrontation. I turned my back on him and through my interpreter told him he was not senior enough for me to talk to, that I would talk only with his commanding officer. Then I used his trucks to transport us and our gear to his headquarters. I made him ride up front in his sedan with the driver. I got in the back seat with my interpreter.

BB: This was a situation that could have gone downhill very rapidly if you didn’t do exactly the right thing. How did you come up with the tactics you used in handling the Japanese?

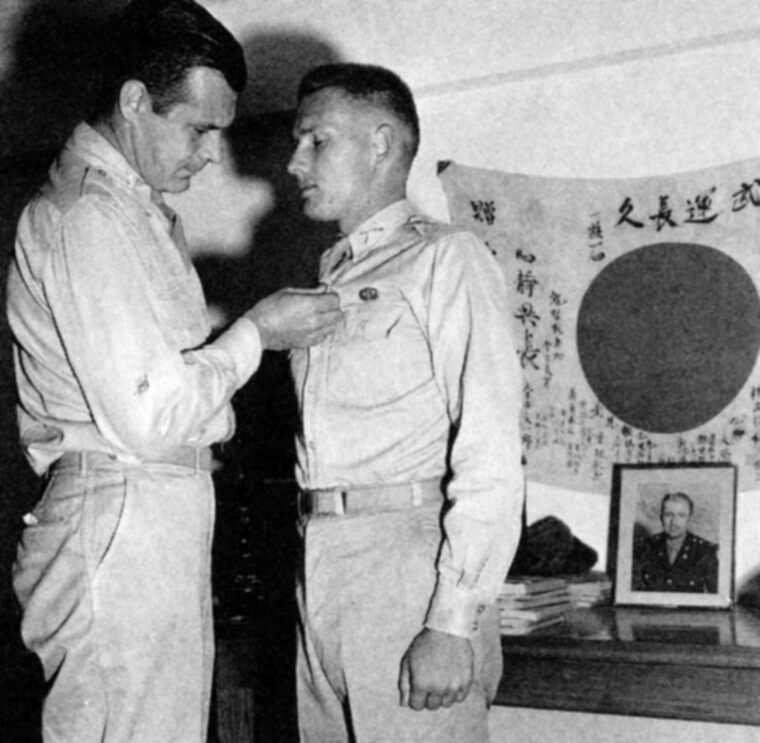

JS: An OSS specialist on the Japanese military had briefed me in Kunming. He had served as an attaché in Japan before the war. He knew the Japanese well and suggested the best way to do things. I was a captain then, and he insisted that I become an instant major. When I jumped in, I was wearing major’s insignia.

BB: You must have been doing the right thing. What happened when you got to their headquarters?

JS: We went into their guard house. I told my team not to go back outside. Japanese guards had surrounded the place and were obviously ready to shoot anybody who tried to “escape.” There was a Japanese captain there, and I told him he didn’t have enough rank to talk with me either. He got on the telephone line and screamed to get connected to his colonel. We listened outside his door, and Ralph could hear the captain saying, “But sir, they jumped in broad daylight, the major insists that Japan is surrendering—and he will talk only with you!” The captain told us that the colonel was on his way and took us to another building that had been a hospital ward. We spent the night there. I made up a roster of guard duty. I wanted somebody awake all the time.

It was a nervous night with a lot of praying. We really had no idea what would happen next. We had been told that MacArthur had issued instructions that Japanese garrisons were to offer assistance to Allies in their areas. Obviously this had not gotten through.

BB: When did the colonel arrive?

JS: The next day. He came from his headquarters on the island’s northern coast. The meeting room had been arranged with him in the place of honor. I changed that, put our people there. That didn’t make him happy. I told him how things stood. I would not accept his surrender—a Chinese army coming from the mainland would take it—and I wanted to see the senior POWs. They quickly brought in the senior Australian, Lt. Col. W.J.R. Scott, and a Dutch officer.

BB: How many POWs were on the island?

JS: Our planning figure was 400, but by the time I got there it was just over 390. They were in terrible shape, dying at a rapid rate because of malnutrition and the diseases that came with it. The POWs were deliberately starved.

When Lt. Col. Scott came in, I moved the Japanese and put him and the Dutch officer at the table. Then I told the Japanese we needed food, medicine, and medical care. I commandeered all transport, food, and medical facilities for the POWs. They went from two meals a day to four and then five small ones, which turned out to be the right thing. It was difficult. We had lost supplies and our radio in the drop and were out of contact with Kunming. I had arranged that every day after our drop a recon airplane would fly over the DZ, and I would display panels to indicate our situation.

I took the first trainload of ambulatory POWs to the southern tip of the island where they could be evacuated, and we got ambushed. There were Chinese guerrillas in the hills. They tore up the track and derailed the train. We had a Red Cross flag on the train and didn’t get fired on. A Japanese repair team got us going again. We got to our destination late that evening. There was an unused airfield there, and my radio operator found a powerful Japanese transmitter, got it working, and contacted Kunming. They didn’t believe it was him and challenged him until he finally convinced them.

We asked for a doctor. When the first airplane from Kunming flew over the field, a doctor parachuted from it and dislocated his shoulder. My medic had to set it, and now I had a doctor with one usable arm.

We filled the craters on the runway, and a C-47 landed. I was trying to establish contact with escaped POWs or others who were in the hills or with guerrillas in the interior. When the next plane landed, I took the pilot chutes from reserves, attached a bottle of atabrine and a note in Chinese, Japanese and English, saying the war was ending and we were here to retrieve all Allied personnel on the island. Then we buzzed the villages and dropped the small chutes. The atabrine established that the message really came from the Americans.

Our supply service sent over an aged lieutenant colonel with no combat experience. His instructions were to relieve the OSS group, which he took to mean that he was to take over and send us out. He was obnoxious to OSS personnel and antagonistic to intelligence operations. Meanwhile, the Japanese had accused my deputy on the other side of the island of misconduct, and I had to go there. I used an incoming airplane and jumped free fall to get there.

I learned that my deputy had not done anything wrong, but that he had found a camp with about 5,000 Chinese slave laborers. The conditions at the camp were unbelievable, worse than anything we had seen. We provided what food and medicine we could and raised their priority on incoming supplies.

I rode the train back to the coast with the last load of POWs. I found that the lieutenant colonel had made a complete fool of himself while I was gone. He went to a Japanese dinner party and insisted my people go. He toasted the Japanese and made outrageous statements, saying they if they had just followed up on Pearl Harbor our positions now would be reversed. My people were outraged. Then he told the Japanese that they would not have to deal with me and my team. I recommended to Kunming that the OSS team pull out, and they agreed.

We left on an Australian destroyer for Hong Kong and arrived in time to witness the official end of the war. That evening we sat on the veranda of the Peninsula Hotel and watched the assembled fleet set off pyrotechnics.

BB: What a great way to end the war!

JS: After so much destruction, the POW rescue mission was a satisfying thing.

BB: Your days with the OSS were just the beginning of your long and eventful career. What strikes you when you look back?

JS: It’s clear that Donovan really understood that Special Operations were to be conducted as unconventional warfare. We were given a mission and sent off to do it with resources we had, whether we were in occupied France, China, or Vietnam. We went in with very small teams. The concept was that we would train the indigenous people and let them conduct the operations. Today we’re losing that. The emphasis now seems to be on direct action—to launch an attack with our own highly trained people to kill the enemy or kick down doors. There seems to be too much emphasis on the direct action part of special operations—rather than keeping our own participation low, and training the indigenous people to do the job.

General John K. Singlaub After the War

General Singlaub continued his distinguished military career. Immediately after World War II, he was chief of the military liaison mission to Mukden, Manchuria. He served two combat tours in the Korean War. In the Vietnam War he was the commander of the Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Force (MACSOG). In addition to his service in three wars, he held many other important positions in the United States and abroad and was instrumental in establishing the U.S. Army Ranger training center at Fort Benning, Georgia. General Singlaub passed away in January 2022 at the age of 100. His career is chronicled in his autobiography, Hazardous Duty—An American Soldier in the Twentieth Century.

Bob Bergin is a former Foreign Service officer and Southeast Asia specialist who writes about aviation history in Southeast Asia and China and on the OSS.

RIP, General, and thank you for your distinguished service!