By Louis Ciotola

The stereotypical Viking and his method of warfare have long been etched in the popular mind. Images of hairy, axe-wielding, and horned-helmeted barbarians raiding coastlines amid a frenzy of rape and pillage have for centuries filled our collective consciousness, as well as our desire to be entertained. But, as so often occurs, history tells a different story.

Much of what we thought we knew about Vikings and Viking warfare has been passed down from idealized Norse sagas. A great deal of the information contained therein, when placed against archaeological and contemporary evidence, proves more fiction than fact. Nevertheless, the popular image of the Viking warrior is not entirely shattered, and the history of the Viking Age remains monumental in both its significance and ability to excite the imagination.

The Vikings were Norse seafaring warriors from Scandinavia who traveled to distant lands primarily for the purpose of raiding. The term “to go a-Viking” literally meant to go plundering. The Vikings that came to wreak havoc on Western Europe and the British Isles originated in Denmark and Norway, though their victims, most notably the Anglo-Saxons, tended to lump them all together as Danes. They left their homes seeking wealth, prestige, and later land on which to settle. Although their victims often considered them to be nothing more than bloodthirsty pirates, the Norse themselves believed that to go a-Viking was a practice reserved for the honorable and courageous.

The Viking Age in the West lasted roughly from the end of the 8th century to the mid-11th century, for many ending romantically with the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. During the first period of Viking activity, Norsemen were almost exclusively raiders, opportunistically striking at England, Ireland, and Francia, which roughly constituted modern-day France. Around the mid-9th century, though, they began to settle in many of the lands they had ravaged, integrating themselves into the European system to which they had previously been so alien. Throughout both periods, the Viking warrior distinguished himself as one unique to his time and place. For 300 years he gave the Anglo-Saxons, Irish, and Franks little respite, forging a terrible and often distorted image that would last to the present day.

No single explanation suffices to fully reveal why the Vikings suddenly exploded on Western Europe and the British Isles during the final years of the 8th century. Many historians cite Scandinavian demographic changes as the key, chiefly a rising population in combination with a subsequent need for land. Others focus on political change in the region, which left many dispossessed. The relatively new use of the sail in the northern lands made Viking expeditions possible, while the aggravating activities of Christian missionaries may have instigated reprisals.

The most alluring explanation is economic. Thanks to a recent boom in trade throughout Western Europe, the Norse appetite for wealth was whetted. In England, for example, the minting of gold and silver coins to facilitate that trade proved an especially tempting motivation for the would-be Viking. Maldon, the scene of a famous battle in England in 991, was targeted because of its mint, while across the Channel Vikings raided Dorestad in Frisia three times between 834 and 837 to loot its royal mint. With little need for a standing army at home in remote Scandinavia, at least in the early days, the Vikings were free to sail west in pursuit of dreams of wealth and adventure.

The West was easy pickings. Neither England nor the Frankish Empire, which would collapse into civil war less than a generation after the death of Charlemagne in 814, were unified enough to decisively face the new threat. Europe lay virtually undefended, its resistance too sluggish to thwart Viking hit-and-run tactics. For decades the attackers bounced between the British Isles and Francia, demonstrating an acute sensitivity to the political and military vulnerabilities of their victims as they probed for soft targets. Only complete political unity, as later illustrated by Muslim Spain and Alfred the Great’s England, served to stem their fury. The greatest motivator for the Viking warrior soon became his own repeated success.

In 793, a small Viking fleet landed on the tiny island of Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumbria, site of one of the holiest places in England, the monastery of St. Cuthbert. What happened next became legend. The Vikings, who had seemingly come out of nowhere, proceeded to sack the monastery, slaughter its host of monks, and leave with all its treasure as well as a handful of captives. The pure scale of the blasphemous act, perpetrated by heathen barbarians, reverberated throughout Christendom. Far distant at the court of Charlemagne in Aachen the scholar Alcuin wrote of the Viking exploit, “It was not believed such a voyage was possible.” For Alcuin and many like him, that God would abandon his flock to merciless pagans was unfathomable.

The Viking attack on Lindisfarne was not only fathomable, it was also predictable. Although Lindisfarne has been celebrated ever since as the first Viking raid, it was hardly the case. The Vikings had struck as early as 787, when three of their ships landed in Dorset, resulting in the murder of a tax man after a brief skirmish. What had instead made Lindisfarne stand out were the scale of the brutality and that such brutality soon became the norm.

Over the course of the next two decades, beginning in 795, the Vikings struck repeatedly, ravaging the Hebrides, Ireland, and Scotland. One of the largest raids occurred at Iona in Scotland in 806 when they butchered 68 monks along a shore that forever after became known as Martyr’s Bay. By then, small fleets were already biting the Frankish coastline as well. Ironically, England, site of the most famous raid, was largely spared. According to chroniclers, a Viking force attempting to attack the monastery at Jarrow, having been stranded when its waiting fleet was destroyed by a storm, was trapped onshore and massacred by a group of vengeful defenders. Apparently traumatized, the Vikings would not return to England for another 40 years. Fate granted the rest of Western Europe no such relief.

Besides being holy sites, monasteries were exorbitantly wealthy and typically overflowed with treasure, making them obvious targets for Vikings seeking instant riches. Their lack of defense and frequent placement along coasts for purposes of trade made the temptation irresistible. Any community sufficiently wealthy and isolated could be targeted. The objective of the Viking warrior was simply to grab what he could and make a quick escape. Treasure, material wealth, cattle, and slaves constituted the plunder. Such things could raise a Viking’s standard of living and prestige, while kings such as Olaf Tryggvason and Sven Forkbeard of Norway could fund political ambitions at home.

The dividends of raiding bore enormous potential. Goods stolen in one place fetched a high price on the market in another. Captives of high status could be ransomed, like the Abbot of St. Denis and his brother in 858, who together brought in an astounding 686 pounds of gold and 3,250 pounds of silver. Meanwhile, those of low status became slaves. In one raid on Armagh in Ireland in 869, Vikings carried off more than 1,000 unfortunate individuals. The Vikings in Ireland even learned to ransom holy relics, such as the body parts of deceased saints, rather than discard the seemingly worthless items amid their scramble for more traditional loot.

The key to pulling off a successful Viking raid was speed. Because it was impossible to protect an entire coastline with anything other than weak local means, the Vikings could hit a target and flee the scene before sufficient defenses could be mustered. The Norman historian Dudo of St. Quentin lamented in 820, “If you by chance go forth to contend with them, oh! Either you will die or they, extremely swift, will return to their ships having slipped away in flight.” Only poor weather, as demonstrated at Jarrow, brought guaranteed respite. For that very reason, as evidenced in their poetry, many Irish came to dread calm seas.

Viking raiders almost certainly practiced a specific set of tactics. The raiding party, after establishing a base camp on shore, likely divided into groups to protect its ships and escape route, cut off the target, and attack it. Those parties originated from larger Viking fleets; for instance, the raid on Lindisfarne was likely part of a larger expedition to the Hebrides. Each raid brought in valuable new intelligence about the surrounding area, allowing the Vikings to confidently select their targets, often deep upriver into the very heart of a country.

The most intangible element to Viking success in conducting these early raids was the same factor that made them so despised—a lack of Christian morality. The psychological shock of pagans burning and murdering in holy places spread terror that undermined resistance. In the eyes of his victim, the Viking warrior was a preordained punishment from God.

Seemingly as invincible was the Viking longship, which had no rival as a transport vessel. Powered by both sail and oar so that it need never rely entirely on wind, it could cross oceans using the stars and a simple sun compass to navigate. Drawing very little water, the longship could penetrate nearly every waterway, extending the Viking reach inland to those who would otherwise have been considered a safe distance from seaborne invaders. Constructed to facilitate speedy disembarkation, few local communities had much of a chance once their lookouts spotted longships on the horizon.

The size of a Viking raid was best calculated by the capacity of the longship, which could carry up to 35 warriors. During the first few decades of Viking activity, the number of ships reported was relatively small, meaning Viking numbers amounted to the low hundreds. A typical raid was three to six ships. Later, after 850, reports of fleets of more than 100 were common, translating into Viking armies in the thousands, though many such accounts were doubtlessly exaggerated. However, the Vikings’ ability to establish winter bases in hostile lands supported such large numbers. Even when a raiding party was small, speed and surprise gave it strength disproportionate to its seemingly insignificant size.

When raiding or on campaign, Viking warriors were divided into warbands called lids. Each lid was a king’s private retinue of warriors, making recruitment a personal affair. In the years before Denmark and Norway were unified into cohesive states, there were numerous kings, often engaged in direct competition, and hence many lids. They could also be led by jarls, which roughly translated into earls, although a king’s lid was generally larger. In Scandinavia the lids served as local defense forces, but abroad they were the instrument of invasion. Often on campaign, lids would unite when kings and jarls held a mutual objective, the most famous example being the so-called Great Heathen Army that marched the length and breadth of England throughout the late 9th century. Once that objective had been obtained, the lids would disperse. It was not until the days of Sven Forkbeard in the early 11th century that national militaries based on a crude form of drafting would appear among the Vikings.

A Viking joined a lid based on the reputation of the king that led it, which was in turn based on several factors. One key factor was the king’s potential to lead his warriors to material gain. Another key factor was the heroic exploits of his men, which would often be recorded in skaldic verse and runic inscriptions. Some, like Hakon the Great, got started as young as age 12, which was not uncommon among Vikings in general. Plunder, fame, and political gain were the typical objectives of the king. Considering the hazards of their chosen vocation, kings anticipated short lives. The successful king encouraged his warriors by always leading from the front. As Magnus Barefoot of Norway put it, “Kings are made for honor, not long life.”

Because of the nature of their employment, Vikings possessed an independent streak that a king needed to bear in mind. He best maintained loyalty by allowing his men a large amount of freedom in decision making. Often targets were determined spontaneously based on the whims of the warriors, usually as a result of some unforeseen discovery or chance bit of information. A king might even take his warriors’ advice in regard to tactical matters; King Olaf of Norway did so when he placed his poorer men at the front of his assaults with the reasoning they would fight the hardest.

Much of what was written of the Vikings comes from the sources of their victims, so that the picture of the typical warrior has come to be somewhat distorted. Often portrayed as giants, the average Viking was only a few centimeters taller than his Anglo-Saxon or Frankish contemporary. Furthermore, Vikings were not the hairy brutes of legend. They took proper grooming seriously, especially in regard to their commonly long beards, the braiding of which served both a cultural and practical purpose.

Only two to three percent of Norse males chose to go a-Viking. Most of them were free farmers that saw little hope for a better life in destitute Scandinavia. The skills learned from hunting provided them with a talent in weaponry easily converted to warfare. Because Vikings fought for personal reasons, be they wealth or adventure, their fighting spirit was high in comparison to those who fought for a ruler or a state toward which they had little real connection.

Once united, a band of Vikings formed a bond of loyalty known as a felag in which discipline was maintained through a system of honor. With Odin, the god of war, as their patron, the Viking ideal was to follow their leader to the death. Bravery would be richly rewarded in Valhalla. While death on the battlefield was revered, death in flight was an inerasable shame. Consequently, the Viking ideal was to always stand their ground, though retreating in battle was hardly unheard of. Only amid treachery was flight permissible. Vikings always treated each other with honor, dividing spoils as evenly as possible while ironically considering theft to be a cowardly practice.

Like most soldiers of the era, a Viking went to battle with a variety of weapons that he was responsible for procuring himself. To be considered an asset, each Viking needed at minimum a shield, sword or axe, and a spear. Anything less would have been detrimental to himself and his comrades. Metal weapons were in short supply in Scandinavia. Much that was not taken from the dead was imported, primarily from the Rhineland where well-known craftsmen like Ulberht, whose name was inscribed on many Viking swords, operated and sold their products to the Norse despite Frankish prohibitions against it. Undoubtedly, the finer blades were imported, as on average the Frankish warrior possessed a stronger sword. Once imported, the blade was often finished in a Scandinavian workshop and sold. For a Viking, a weapon was a symbol of status, and accordingly they were in the habit of awarding their arms proper names. For example, Magnus the Good wielded an axe named Hel, and Earl Sigurd dubbed his sword Bastard.

Popular images of Vikings usually depict them bearing axes, but it was the sword that the Viking most cherished as the symbol of his power, rank, and wealth. Viking swords were primarily single-handed, double-edged swords anywhere from 70 to 90 centimeters in length and weighing between four and five pounds. Most were made of iron rather than stronger carbon steel but were pattern-welded at the core from bundles of iron rods to give them greater strength and increased pliability. A fuller down the center of the blade reduced the weight.

Most Viking swords possessed both an upper and lower pommel to protect the hand. Pommels were made from iron or copper alloy, silver, bone, or antler and were often decorated with silver or copper patterns, typically in the shapes of animals. Handles were covered by wood, leather, horn, or bone. Scabbards were made of wood and sometimes covered in leather.

The Vikings used their swords as hacking weapons. Spears and the occasional single-edged knife, known as a scramasax, were reserved for thrusting, most often during the initial phase of close combat. The Viking spear was heavy, though light enough to be used one-handed with a shield, made of iron, and pattern-welded. The shaft was up to two meters long and fitted at the end with a 10- to 20-inch, leaf-shaped head that was either angular or rounded. Rarely, the spearhead was decorated with silver, copper, or brass. The Vikings also used short, lightweight spears and the occasional heavy two-handed spear, which could penetrate mail. The heavier spear was sometimes fitted with wings to prevent it from becoming lodged into the body of an enemy.

The famous Viking axe was a common weapon given only the scarcity of the more favored sword. The most used axe was not the often imaged two-handed broad axe, which came to frequent the battlefield only later during the Viking Age. For most of the era, a short, single-handed axe was much more common, although a much longer Danish version with a 22-inch blade made frequent appearances. Axe heads were made of iron and usually plain with only a few decorated with silver and copper. The largest came armed with projecting spurs.

Axes were heavy weapons that relied as much on gravity as strength. Nevertheless, only the strongest men wielded the heavier varieties, which could smash right through an enemy’s shield in one solid blow. Because of the weight and reach of the longer, heavier axes, both of the one- and two-handed varieties, tightly packed ranks were an impossibility as the swing of the weapon could just as easily dispatch friend as foe.

Though close combat kills were considered nobler by the Viking warriors, they nevertheless used projectile weapons in battle, specifically at the start of an engagement as a way to clear a path for short-range fighting. Both javelins and arrows, for example, were used extensively at the Battle of Maldon before the two armies clashed at close quarters. The Vikings employed the longbow, which was approximately 192 centimeters in length. The bow fired birchwood arrows with iron heads at a range of 200 meters, but was most effective at close range where it could penetrate mail.

Mail shirts were rarer among the Vikings than their contemporaries, being common only among those of high status. Weighing up to 70 pounds, many warriors found them restrictive. According to legend, the army of Harald Hardrade chose not to wear any armor at all, though that was extremely unlikely. Despite some controversy, metal helmets were not uncommon, many being fitted with eye and cheek guards, as well as mail to protect the neck. There is no evidence to support the use of leather helmets, while the popularly depicted horned headgear was entirely fictitious.

Much more fundamental for defense than armor was the Viking shield. Viking shields were circular, roughly three feet in diameter, and made of wooden planks that were strengthened by iron bands along the rim. The famous medieval kite-shaped shield appeared only at the end of the era. Some shields were reinforced by a leather cover, while others were richly painted, usually in skaldic verse. Grips were normally wooden, but on occasion made of brass. Cheaply made, the Viking shield rarely survived a single battle. One blow of an axe was almost certain to shatter it to pieces; however, a lighter weapon would often become lodged within the wood after which a quick jerk of the arm might successfully disarm the attacker.

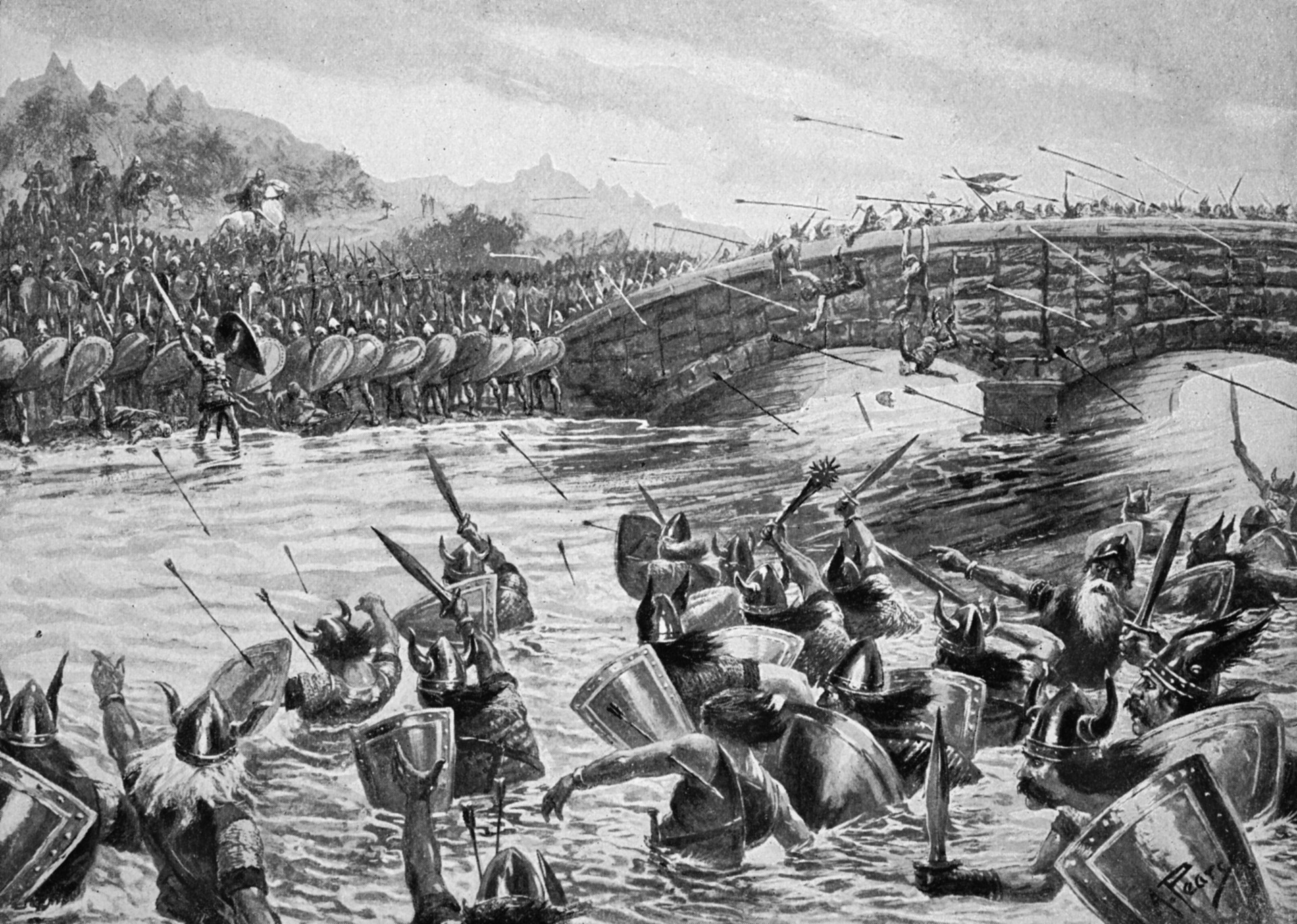

Chroniclers often depicted the use of shield walls in battle, such as at the battles of Edington and Maldon, but exactly what that meant remains debated. It was unlikely that Vikings employed the Roman-style tactic of interlocking shields, as it would have prohibited them from using their slashing weapons, at least without doing serious harm to their fellow warriors. The term shield wall was nothing more than an expression for an army in line formation. Regardless, the meeting of two such lines often resulted in a bloody struggle lasting all day, ending with merciless slaughter of the side that broke first.

During the first several decades of the Viking Age, raiding was exclusive to the warmer months. A raiding party would land, sack, and return home content with its plunder. But by the end of the first quarter of the 9th century, the nature of the attacks had begun to change dramatically with the establishment of winter bases. Suddenly, raids being led by increasingly higher nobility with larger and larger forces using river systems to penetrate ever deeper into the interior of the European continent, and shortly thereafter the British Isles, had become the norm.

Viking bases were strategically placed to control river systems. It was typical to choose an island as a base because of its defensibility. One of the earliest Viking bases in France was located on the island of Noirmoutier near the monastery of St. Philibert. Established in 819, it allowed the Vikings to dominate passage of the Loire. The Viking return to England in 850 was marked by wintering on the Isle of Thanet off the Kentish coast, while the Isle of Sheppey was used to control the Thames.

The preparation for large raiding expeditions commenced in the winter with the founding of a base. The Vikings constructed fortresses of earth and timber in which to gather supplies, keeping in mind escape routes when plotting the locations. The raiding season began each spring. Anyone living in a city or town lying on or near a navigable river was at risk of attack, which for Francia and Ireland meant virtually everyone.

Most raiding, as with all military operations of the period, occurred during the day, although on occasion Vikings risked the confusion of darkness such as at Bordeaux in 848. It was popular to take advantage of their adversary’s religion and strike on Christian holidays when the enemy would be distracted and the potential loot at its greatest. Fortunately for the Vikings, the Christian calendar of the time provided no shortage of those days. They struck at Kildare in Ireland on St. Brigid’s Day in 929 and Iona on Christmas in 986. One of the largest raids of all occurred during the Feast of St. John the Baptist in 843, when the Norsemen butchered a worshipping congregation inside the cathedral at Nantes.

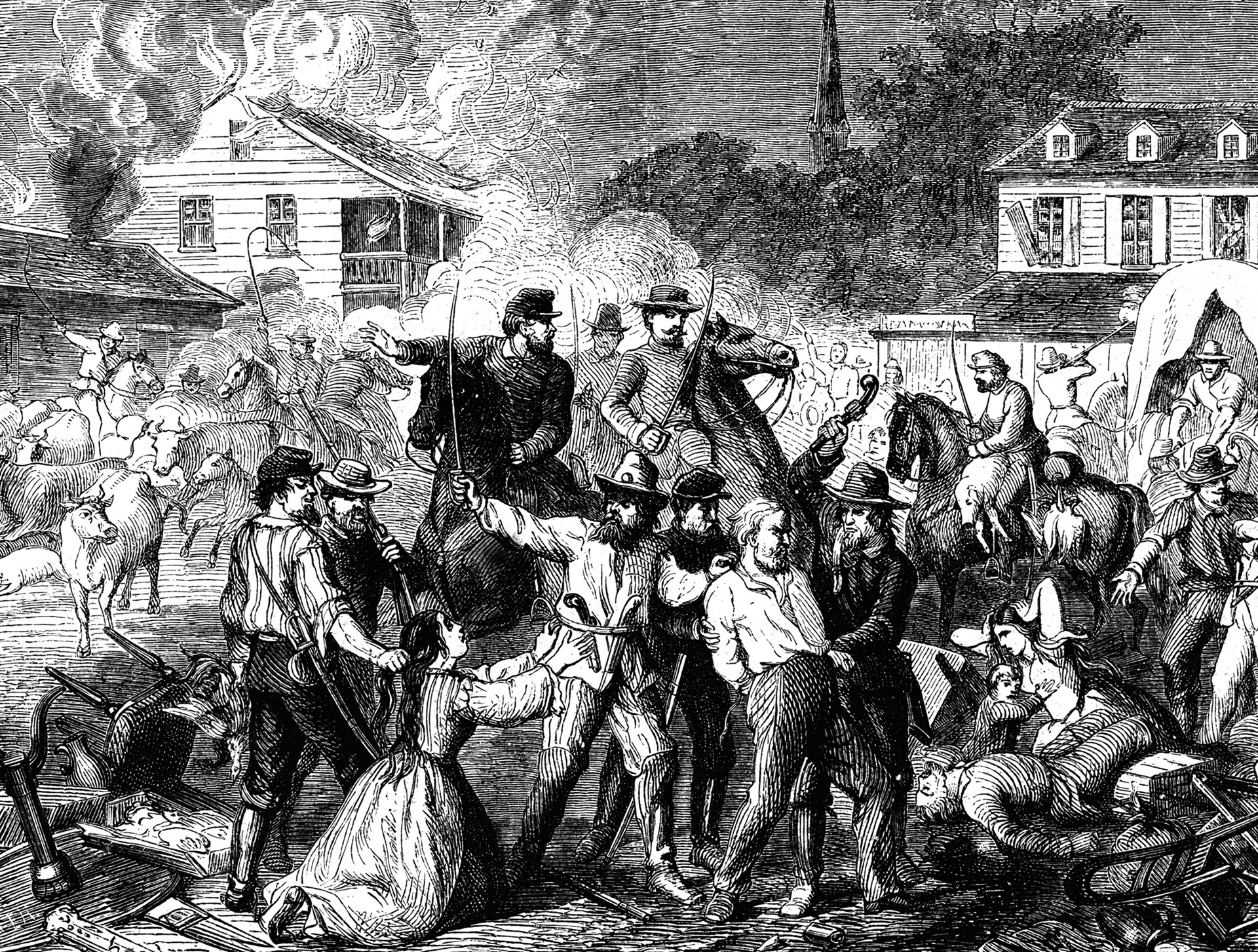

The most famous of all such raids was on Paris in 845. The attack up the Seine to Paris was supposedly led by Ragnar Lodbrock, a legendary ruler whose existence remains in doubt, but who according to the sagas liked to strike during Christian feasts. After defeating a smaller force outside the city that had moved to intercept, Ragnar’s Vikings hung 111 of their prisoners in full view of the remaining Franks on the opposite bank of the river. The act, which was likely a mixture of ritual and psychological warfare, served its purpose. The Franks stood aside as the Vikings entered Paris on Easter Sunday, March 28, and plundered the city. Twelve years later, Paris would be sacked again, this time by Ragnar’s son, Björn Ironside.

Cities were not always wide open for the Vikings to do as they pleased. As Viking operations grew larger, the Norsemen inevitably had to become more adept at siegecraft to strike more prominent targets. Only concerned about material gain, Viking armies almost always bypassed forts to instead besiege wealthy towns. In the early days of Viking raids, many cities in Francia were vulnerable to attack as they were protected only by dilapidated Roman walls. At Nantes, for example, it was only a matter of scaling those walls and smashing open the cathedral doors. But as the Vikings became a more anticipated threat, defenses improved and the besiegers had to become more innovative.

No siege was better known during the Viking Age than that of Paris in 885-886. Much of what was known about the siege came from the writings of the French monk, Abbo of Fleury. It all began when a Viking army amounting to a dubious 40,000 men aboard 700 ships under the sea king Sigfrid approached Paris by way of the Seine in late 885. Judging the target not worth the effort, Sigfrid offered to leave Paris in peace in return for free passage past the city’s two fortified bridges. The city’s defender, Count Odo, refused. Instead, he and his paltry 200 warriors were determined to resist inside their citadel of Ile de la Cité until an army under the Frankish King Charles the Fat could come to their relief.

Abbo described a number of ways that the Vikings attempted to reduce the Parisian defenses over the next several months. They used siege engines against the bridges and towers, fired poison arrows over the walls, launched incendiary boats, and even filled the moat with dead men and animals. While the siege was underway, the Vikings plundered the countryside. According to Abbo, they also constructed a 16-wheel oak battering ram with its own roof for protection, but it was all to no avail. By summer they had run out of time with the arrival of King Charles.

Then a most remarkable thing occurred. Rather than crush the tired Viking besiegers, Charles granted them passage to plunder Burgundy. It was the ultimate act of betrayal, one that Odo refused to recognize. He continued to man the two fortified bridges, compelling the Vikings to portage their ships from the Seine to the Marne. The decision turned out to be most politically unwise for Charles. His enemies deposed him the following year.

Not all major Viking forays took them deep up river into the interior of a country. Some traversed great distances to acquire their fortunes, but none more famously than the chieftain Hastein, who penetrated the Mediterranean in 859. With a fleet of about 60 ships, Hastein sailed from the Loire down the French coast to Muslim Spain with the intention of raiding the coastal towns of the Umayyad Caliphate. Far more united than their Anglo-Saxon and Frankish contemporaries, however, the Muslims easily repelled Hastein. Undaunted, Hastein continued around Spain and through the Strait of Gibraltar, hoping to surprise those who as yet knew nothing of the Viking scourge.

After establishing a base on the island of Camargue, which controlled entry into the Rhone River, the Vikings fanned out in all directions, possibly even as far as Toulouse. But Hastein’s true dream was to sack Rome, the center of the Christian world. Nothing would bring him more glory. Fortunately for the Eternal City, he would never find it, but his attempt to, as recorded by Dudo of St. Quentin, would go down as Viking legend.

Hastein’s fleet moved along the coast of Italy until stopping at the town of Luna. Mistakenly believing it to be Rome, he was determined to take the place. Luna was well protected, so it would take all his cunning to gain entry. Hastein resolved to play on Christian sensibilities. Feigning illness and a Christian identity, he requested entry into the town so that he could receive last rites. Feeling obligated out of Christian charity, the town accepted. Hastein entered Luna, received the rites, and departed peacefully, having earned the town’s trust.

Shortly thereafter, the Viking fleet sent a messenger with news of Hastein’s death and a request that Luna grant him a proper Christian burial. Feeling secure, the town again granted the request, this time allowing the entire Viking force entry. The burial called for a procession in which Hastein’s body was carried on a bier to the cathedral. At the given signal, however, a very much alive Hastein leaped from the bier and with his warriors commenced the usual sacking. According to Dudo, that plundering turned to massacre when an enraged Hastein realized that the town was not Rome. Nevertheless, the windfall from the expedition was huge, and his fleet left for home laden with riches. Unfortunately, much of it was lost at Gibraltar where it was caught by a vengeful Muslim fleet armed with flamethrowers. Only 20 of the 60 ships escaped destruction.

Massively powerful fleets were not necessarily required to cope with the Vikings. There were other methods to alleviate their threat. One such method was the payment of Danegeld. Because Vikings wanted material gain at the lightest cost possible, they were highly susceptible to being bought off. For the Vikings it was considered tribute, while their victims felt more comfortable calling it a bribe. In return, the Vikings refrained from raiding a target. The sum could be quite high. Charles the Bald paid Ragnar Lodbrock 7,000 pounds of silver to quit Paris following its sack in 845, and Charles the Fat paid 700 livres and granted the right to plunder Burgundy in 886.

As the payment of Danegeld became more common, the Vikings became craftier in ensuring its extraction. While the payments may have temporarily kept the peace, they also encouraged Vikings to return in the hopes of acquiring more. Such was the case of Sven Forkbeard and Olaf Tryggvason, whose repeated trips to England in the late 10th century were for the purpose of demanding ever increasing sums, usually to fund their political ambitions back home. The threats to attack unless paid were nothing more than blackmail, but they proved an effective strategy for guaranteeing long-term wealth at the cost of fewer warriors.

Vikings were also often susceptible to political manipulation as another method for averting their fury and possibly deflecting it in another direction. The sack of Nantes, for example, was at least partially the result of a deal made between the Vikings and Count Lambert, who was rebelling against Charles the Bald, while that same Charles paid a Viking named Weland in the late 850s to besiege another group of Vikings on the island of Oissel. Those same Vikings in turn paid Weland to allow them to escape.

These sometimes confusing examples of opportunism were extensive. Pippin II of Aquitaine fought with the Loire Vikings in the sack of Poitiers in an attempt to gain the throne, an act that led to accusations of paganism and execution in 864. Charles the Fat allowed the Vikings passage to Burgundy in 886 because he feared Burgundian disloyalty, while the Irish King of Osraige, Cerb all mac Dunlainge who ruled from 842 to 888, famously played Vikings off against each other throughout his long reign.

The most famous bargain struck between a Viking and a potential victim occurred in 911 between Rollo and Charles the Simple. Rollo was a Norwegian who had been exiled from Norway by Harald Fairhair for committing strandhugg, the plundering of his own lands to fund campaigns. Rollo was notorious throughout northern Francia, and Charles saw little choice but to placate him by handing over through treaty the province of Normandy, making the Viking a French duke. Significantly, it was Rollo’s lineage that would later produce William the Conqueror.

When Danegeld and political machinations failed, the Vikings’ victims had to rely on their defenses. As demonstrated by Spain, the most effective ingredient in a successful defense was political unity. After the deposition of Charles the Fat, Odo and Arnulf of the East Franks united and successfully drove the Vikings out of Francia and back to England. But most defenses remained localized, often through peasant bands, which sometimes proved more trouble than help. Professional soldiers rarely arrived at the scene of a raid in time. Tactically, entire coastlines and river systems were too large to completely defend, but rivers could be blockaded, as demonstrated by the fortified bridges at Paris in 885, and that was done increasingly after 859. Meanwhile, new fortifications began appearing in Francia during the last decades of the 9th century to replace the old Roman walls that had proved so ineffective at places such as Nantes. They played a large role in decreasing the number of Viking raids.

After more than half a century of raiding, the Vikings began to slowly evolve toward empire building. The conquest and settlement of Ireland was long underway, having commenced around 840. Years of successful raiding up the Loire, meanwhile, eventually tempted some toward territorial acquisition. But it was England, beginning with the occupation of York in 867, which witnessed the biggest shift from raiding to con

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments