By Guillermo Rivera

As a combat veteran of some of World War II’s toughest fighting, Lieutenant Jim McDonald was not easily flustered, but he had a bad feeling about this. The war had ended nine years ago, and now, in mid-April 1954, he was crouched in a fetid Panamanian jungle, carrying a heavy pack and a radio on his back. Around him, 43 other soldiers crouched under trees or any other cover that they could find.

Overhead, he could hear the low-pitched whine of the L-19 spotter plane as it flew over their position. McDonald yelled, “Take cover!” Projectiles fell from the plane and the ground shook with their impact. As soon as it was safe to do so, McDonald ran out and checked the first package he came to—frankfurters and beans were strewn across the ground. Someone was not going to eat tonight.

Operation “Meat-and-Bean-Dodging Time”

McDonald’s unit, consisting primarily of soldiers from the Army’s 33rd Infantry Regiment and a squad of Marines, was five days into a 10-day crossing of the Isthmus of Darien, Panama. The only way for them to receive resupply in the jungle was via aerial drop. With typical gallows humor, the men had christened the operation “meat-and-bean-dodging time.” The unit had embarked on an operation to retrace the journey of the Spanish conquistador who had “discovered” the Pacific Ocean in September 1513, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. Romantic poet John Keats, in the first great poem of his tragically short career, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” had eulogized Balboa’s feat while getting his name wrong: “Or like Stout Cortez when with eagle eyes/ He stared at the Pacific—and all his men/Looked at each other with a wild surmise—/Silent, upon a peak in Darien.”

Cortez subdued the Aztec empire in Mexico, but he never set foot in Panama. Balboa, like Cortez and many of his fellow conquistadors, hailed from the Spanish region of Estremadura. Balboa first embarked for Panama as part of an exploratory expedition led by his countryman, Rodrigo de Bastidas. Balboa returned to Hispaniola, where he unsuccessfully tried his hand at farming. Deeply in debt, he stowed away on a resupply ship bound for Panama, where his fortunes took a turn for the better, and he rose to command all Spanish forces in Panama. His crowning achievement was the crossing of the isthmus with 190 Spaniards and 1,000 natives, culminating in his discovery of the Pacific Ocean (he christened it the South Sea) in 1513.

The significance of the discovery was threefold. It continued Columbus’s uncompleted objective of discovering a water route to the Indies, led directly to Magellan’s voyage of global circumnavigation, and advanced the discovery and conquest of the Inca empire by Balboa’s chief lieutenant, Francisco Pizarro. In the end, however, the discovery did not save Balboa. Six years later he was summarily beheaded by his successor and father-in-law, Pedrarias Davila.

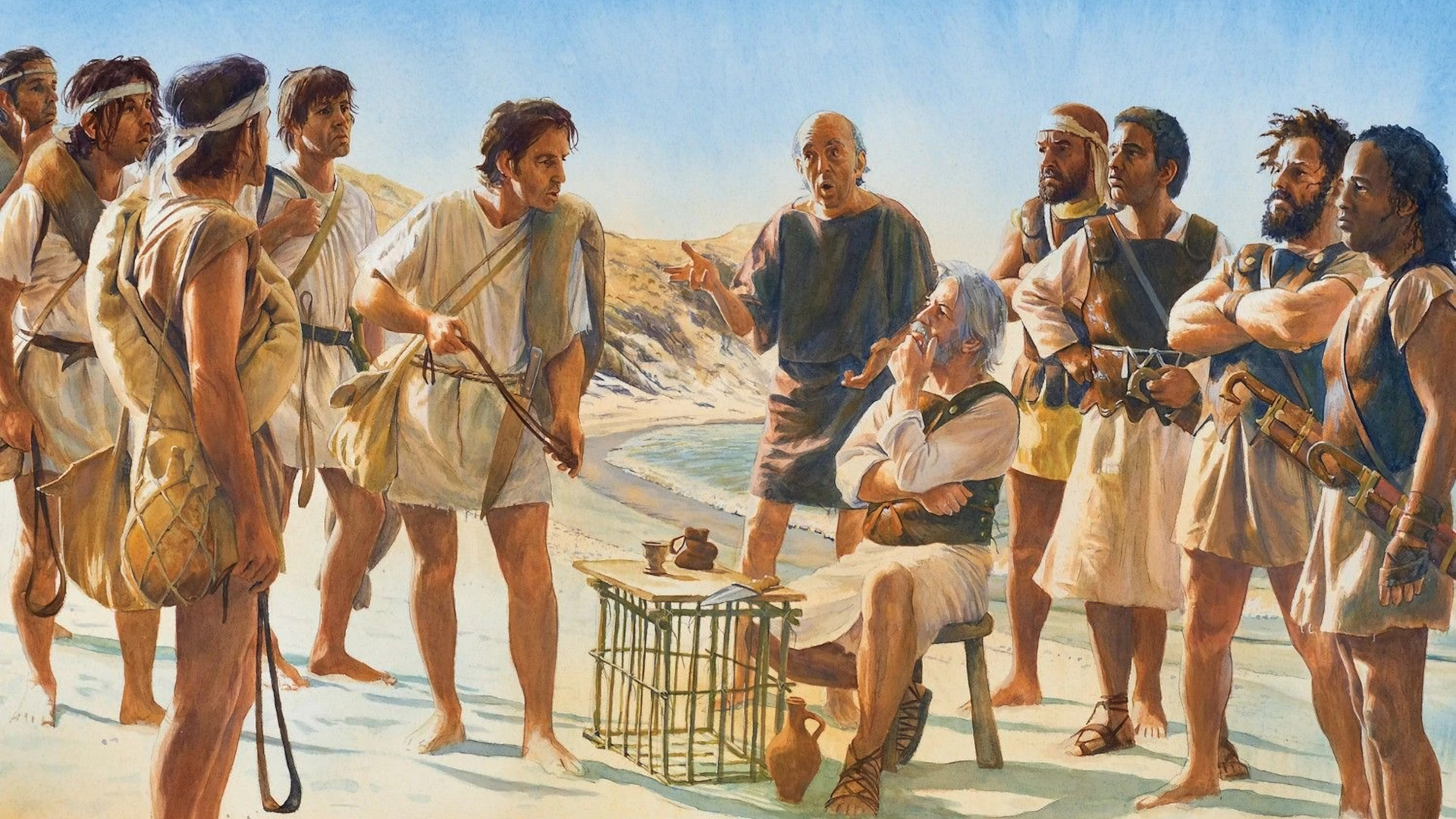

(1475-1519). Spanish explorer. Balboa taking possession of the Pacific Ocean for Spain on September 29, 1513. Color lithograph, 19th century.

As the soldiers of the 33rd bent under their loads, they were seeking the trail of the original Balboa. The trip had been planned quickly after a strange report reached Army leaders concerning the former king of Belgium, Leopold III, and his ongoing travails. When Germany attacked France through Belgium in May 1940, the king led the defending Belgian Army. In his dual role as head of state and head of the armed forces, he surrendered unconditionally to the Germans. He spent the majority of the war as a German prisoner of war at his palace in Brussels. During the war he also met and married a commoner, Mary Liliane Baels, who assumed the title of Princess of Rethy. The nation was deeply divided in its support of the king, due to his actions during the war and his marriage to a commoner. In the face of deep unrest, he abdicated the throne in favor of his son Baudouin in July 1951. After his abdication, he embarked on a series of wanderings to undeveloped areas in South America, Africa, and Panama.

On March 29, 1954, Leopold entered Darien from the Pacific side in an attempt to recreate Balboa’s route in reverse. His small group consisted of himself, noted Venezuelan anthropologist Jose Maria Cruxent, a photographer, a Panamanian National Guard officer, and several Kuna Indians to help guide and carry loads. Accounts varied as to the success and conduct of the king’s 14-day operation, during which time Leopold was feared lost after being held captive by natives in the interior. Hearing of the operation by the former Belgian king, U.S. Army Caribbean Command issued a special directive on March 18, ordering the 33rd Infantry to dispatch a unit of its own to recreate Balboa’s route. The mission was christened “Operation Balboa.”

Preparing for the Operation

On March 20, Colonel George A. Elegar, commander of the 33rd Infantry, called his Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon leader, Jim McDonald, into his office for an overview of the mission. Elegar instructed McDonald to begin an intensive training program involving the Pioneer and Ammunition (P & A) Platoon from the regiment’s 1st Battalion, led by 1st Lieutenant William Lueders. The composite platoon was rounded out with a squad of Marines, a Navy corpsman, two medics from the 33rd, two Signal Corps photographers, and two Panamanian nationals—2nd Lieutenant Carlos J. Martinez of the National Guard and Thomas Guardi, Jr., chief of the government’s mapping division. (One of the noncommissioned officers from the P&A Platoon, Sergeant Guillermo Rivera-Perez, was the author’s father.)

Highly respected within the regiment, McDonald had graduated from West Point, class of 1951. A rarity among his classmates, he had been an NCO in World War II and had arrived at the military academy as a new cadet in the summer of 1947 wearing a Combat Infantryman Badge (CIB) earned with the 8th Armored Division in the Saar-Moselle triangle as part of the XX Corps. He had been wounded twice, once by enemy fire and once by an accidental discharge when a friend was cleaning a weapon. Only the enemy wound was reported.

Individual training for the soldiers and Marines began immediately, with a focus on map and compass reading, physical conditioning, route reconnaissance, machete use, first aid, field sanitation, jungle movement and survival, and swimming. The unit conducted numerous cross-country road marches through hilly jungle terrain, with each man carrying 20 pounds of sand in his backpack. Training continued until two days prior to departure. McDonald and the patrol leaders also embarked on a series of L-19 overflights of the intended route, as maps of the area were scarce and generally unreliable.

Although the directive from headquarters at the U.S. Army Caribbean Command specified four checkpoints—a starting point, an Indian village, Balboa’s hilltop, and the exfiltration point—McDonald had to navigate the remaining terrain and divine Balboa’s original route on his own. During the initial planning phase, McDonald had consulted with Professor Angel Rubio of the University of Panama, the acknowledged expert on the topic. Rubio had also been intimately involved with the planning and routing of King Leopold’s expedition. While McDonald’s patrol was traversing the jungle, Rubio had been a passenger in numerous L-19 overflights of the area.

The First and Only Casualty

After an intensive preparatory period, the men were ready to embark on Operation Balboa. On Tuesday, April 20, the unit traveled down the Atlantic coast in a tugboat and motorized J-boats, disembarking near Sasardi Point, opposite Mulatupo Island. A group of San Blas Indians from Mulatupo helped them ferry supplies ashore in piraguas and was hired to help carry rations for the initial march inland. They were in the presumed vicinity of Acla, the long-abandoned settlement established by Balboa from which he embarked on his historic journey in 1513.

The patrol suffered its first and only casualty requiring evacuation when one of the members fell and severely cut his hand on a machete. Fires were kept burning and guarded every night of the march. The patrol also carried live ammunition for their M1 rifles, .45-caliber pistols, and shotguns. They intended the ammunition for hunting and for self-defense—Darien was correctly viewed as very wild country indeed.

Contact with Natives

The next day the unit departed at 6:20 am on a southwesterly bearing, in the direction of the Morti village that lay on the far side of the coastal hills to their front. Twenty hired Indian porters joined the column to carry C rations and presents for the villagers. Eight porters were paid $24 and dismissed after their loads of C rations were consumed. For the first few days of the trek, the platoon could hear aircraft flying overhead, but the L-19 couldn’t see their signal flares and reported the platoon to be lost.

On April 22, Sergeant Emory Abercrombie and Pfc. Jack Sutch were evacuated to the Acla base camp. Abercrombie had suffered a malarial relapse and Sutch’s arm had swollen alarmingly; both walked back under their own power. At the headwaters of the Morti River, the guides said the expedition was three hours away from the village. A large group of natives met the platoon and ferried two-thirds of them to the village in hollowed-out log piraguas. The platoon had marched 16,000 paces (about eight miles) and traveled 1.5 miles in the piraguas. The village chief assigned them a bivouac site 250 yards from the village. This was the same chief who one month earlier had held Leopold captive for appearing in the village unannounced and without permission.

The next day, having negotiated with the chief, McDonald loaded all but six of the platoon members onto piraguas to travel down the Morti River to its junction with the Chucunaque. Lueders followed a few hours later with the remainder of the platoon. Water was in short supply, but the men found some water holes near a dry riverbed and purified the water with halazone tablets from the soldiers’ canteens. The L-19 conducted a ration drop the next afternoon, with about a third of the rations damaged beyond use.

On Sunday, April 25, the unit made slow progress through thickly vegetated areas that required manual clearing by machete. The sustainable rate of movement was roughly 1,300 yards per hour. Water was running short, and a group was sent back to holes used the day before to fill canteens. Due to poor radio contact with the L-19, only a partial ration drop was conducted, and the men were put on short rations, supplemented by a wild turkey shot by one of the soldiers.

Water remained a problem, with many of the men down to a pint or less in their canteens. Morale remained high, however, and the men chewed the meat of the black palm nut for additional hydration. On the 26th they located an adequate water hole after covering another 12,940 paces.

The patrol continued moving to the southwest and covered some 5,500 paces the next morning. The L-19 pointed them to a logging road that paralleled their route of march, and the next afternoon, after marching another 11,000 paces, they reached a logging camp. The loggers were friends of the Panamanian observers with the patrol, and the soldiers were able to sleep in the camp sheds, wash their clothes and eat native-prepared dinners.

The View from the Top of Hill 2200

On April 28, the platoon got lost. Following native guides who insisted that they knew the trail, the platoon traveled 17,600 paces (81/2 miles) up and down steep terrain but ended up only three miles closer to their hill objective. McDonald dismissed the guides and paid them $10 for their trouble. Aerial reconnaissance confirmed that they were still some 12 miles from the hill, at an azimuth of 250 degrees. Moving 51/2 miles through moderately difficult terrain, the patrol crossed the Cupanati River, which put them within a day’s march of their objective. The L-19 dropped rations that evening onto their hilltop bivouac site; half were recovered in edible condition.

Reveille was called at the standard hour of 4:30 am on April 30. The unit traveled over rugged terrain, reaching a logging road that the aerial reconnaissance had pointed them toward. By 11:45 they had traveled some 6,000 paces up and down steep hills, following the logging trail. Near noon they believed that they were near the objective, but thick vegetation made it difficult to ascertain the specific location of the peak. After an advance reconnaissance element reached the peak at 2 pm, the remainder of the platoon finished its climb 45 minutes later. They had traveled 11,100 paces that day, about 5.5 miles, mostly uphill. Of the 47 men who had started the march, 44 had completed it, a noteworthy achievement in such rugged conditions. For perhaps the first time since 1513, an organized armed force had reached the lofty peak and observed the brackish waters of the Gulf of San Miguel.

In standard military fashion, the 33rd named the objective hill after its elevation. Hill 2200’s elevation was confirmed by altimeter as 2,073 feet by McDonald. The hill was actually part of a linear ridge, itself a spur off a larger hill mass to the north. The ridge was aligned north to south and was topped by two similar hill masses, of which 2200 was the southernmost. Natives knew the hills as El Pechito Parado, or “the Upright Breasts.”

83 Miles in Ten Days

After clearing a helicopter landing strip on the hilltop, the men received a visit the next morning from Colonel Elegar and two aides. They brought with them a monument to be erected on the hilltop. The expedition had already found a stone mound on the hilltop, pointing toward the Pacific Ocean at an azimuth of 190 degrees. Balboa was reputed to have left a similar marker on the hill in 1513. The regimental commander had also brought a barber, hot food, and cold beer for the weary platoon.

Additional visitors to Hill 2200 arrived the next day, most notably Professor Rubio, who regaled the men with tales of Balboa. The following day, the monument was officially dedicated in a ceremony attended by representatives from the 33rd Infantry, U.S. Marine Corps and the Panamanian National Guard. Over the next two days, the soldiers walked to an embarkation point on the Bay of San Miguel, where they boarded boats for a trip to Balboa on the Pacific side of the canal. From there they boarded trucks for the trip back to Fort Kobbe. McDonald and his men had marched a total distance of 162,536 paces, or 83 miles, over a period of 10 days.

Rubio later claimed in a 1962 book that the expedition had climbed the wrong hill, and that Leopold had climbed the right one. Interestingly, a plaque left on the monument by the unit in 1954 has disappeared. Noted Panamanian guide Hernan Arauz, who led several “route of Balboa” treks across the isthmus in the 1990s, told the author that he had never seen the marker. His father, Amado Arauz, himself a well-known Panamanian anthropologist, recently published an article in a Panamanian periodical on the route of Balboa. He received an anonymous response that contained a picture of the 33rd Infantry’s plaque. From the background of the picture, it appeared that it is now a conversation piece in someone’s private library.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments