The degree to which Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan set Northern soldiers on edge is seen by a story that appeared in southern newspapers in April 1862. The eerie tale describes how a tall, bearded man mounted on a fleet-footed black stallion appeared night after night to kill Union pickets in south-central

Missouri. Although taken under fire frequently, the mysterious rider who struck at night always escaped unscathed. Green soldiers said it was Morgan, but that was impossible given that he did not operate in that region. But before the war was one year old, he was a household name throughout the North and South.

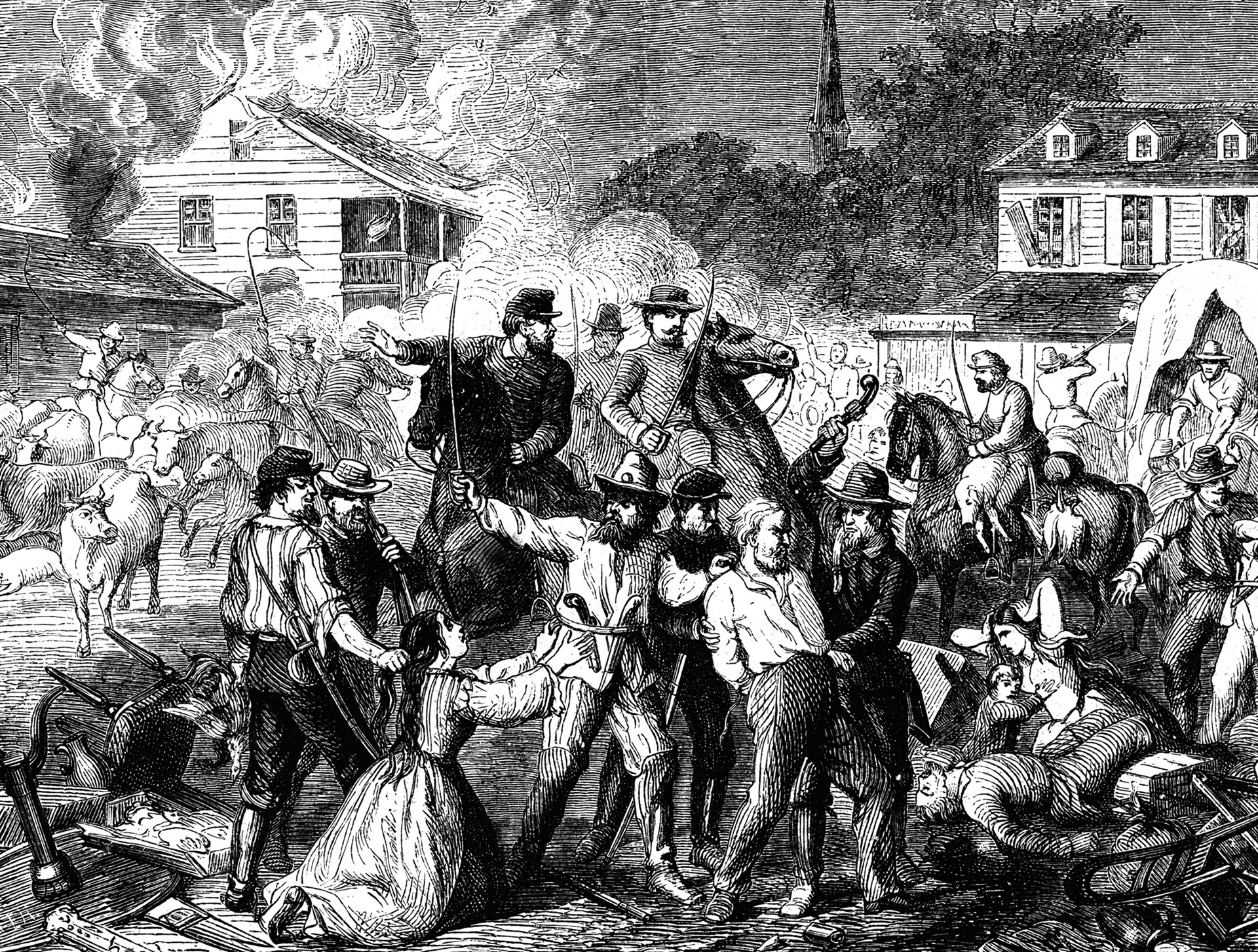

Morgan, whose family had moved from Huntsville, Alabama, to Lexington, Kentucky, opted to join the Confederate army when Kentucky’s neutrality came to an end in September 1861. A veteran of the Mexican–American War, he enlisted in the Confederate service on October 27. Shortly afterwards, Captain Morgan began leading his cavalry squadron on hit and run raids against Union outposts and supply lines. The incident that catapulted him to national attention was the burning of the Bacon Creek Bridge on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad on December 5, 1861. A news item in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper covered the raid mentioning him by name. These and similar exploits earned Captain Morgan a promotion to colonel on April 4, 1862. His command, the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, soon had upwards of 900 men.

The 2nd Kentucky reported to Knoxville, Tennessee, in June 1862 for a month of training with General Kirby Smith’s Army of East Tennessee. During that time, several of the regiment’s companies received the Enfield Pattern 1853 Cavalry Carbine, a shortened form of the full-length Enfield Pattern 1853 rifled-musket made in Great Britain. This became the preferred carbine of Morgan’s Raiders. As the war progressed, many would also carry a brace of Colt revolvers. Morgan drilled his men hard using Dabney Maury’s Skirmish Drill for Mounted Troops. It was a comprehensive manual that described how to fight both mounted and dismounted.

On July 4, 1862, Morgan led his 867-man mounted force on a major invasion of the Bluegrass State that would become known as Morgan’s First Kentucky Raid. Morgan had resolved beforehand that where the enemy was weak he might disperse it with a mounted charge, but for that where the enemy enjoyed superior numbers or was entrenched he would fight dismounted to give his command the same advantages in discipline, movement, and firepower as that reaped by regular infantry.

Crossing the Cumberland River, the raiders headed northeast. Morgan planned to feint at Cincinnati. After fighting a large skirmish at Cynthiana, he turned south for the safety of Confederate lines. He arrived safely in Sparta, Tennessee, having covered more than 1,000 miles in 24 days.

It was a masterful campaign. To avoid being surprised by the enemy, Morgan had used scouts in front, on the flanks, and behind his main force. Moreover, he employed a system of rolling videttes by which handpicked troopers functioned as advance guards that scouted and secured every crossroad until the head of the column arrived.

The only close call occurred when Morgan decided to ride with the advance guard in the early evening on the approach to Lebanon, Kentucky. When they reached a covered bridge on the Rolling Fork River, a member of a Union patrol shot Morgan’s hat off his head. The incident might have ended in tragedy for the Confederacy, but fortunately for Morgan and his men the shot made in the darkness was high.

Morgan received a promotion to brigadier general on December 11, 1862. He always wanted to up the ante by conducting a bolder, more rigorous raid than the previous one. Morgan would get that chance in 1863 when he undertook what became known as Morgan’s Great Raid.

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments