By Al Hemingway

At 2:10 PM on May 7, 1915, Captain Walther Schwieger, commanding the German submarine U-20, was patrolling off the coast of Ireland, looking for British merchant ships. A state of war had existed between the two nations since 1914, and Great Britain had established a vise-like naval blockade, preventing merchant vessels from entering German ports. Because of this, the civilian population was experiencing widespread hunger and malnutrition. Although many nations had condemned the blockade, nothing had been done to lift it, so the German Navy dispatched packs of submarines, or U-boats, to destroy any ships in the English Channel that they suspected of carrying supplies to England. The concept of total war had now taken to the seas.

Peering through the periscope, Schweiger spotted the unmistakable outline of Lusitania, the pride of the Cunard line, steaming toward Liverpool. After some deliberation, the 30-year-old German naval officer made the fateful decision to fire. The torpedo streaked along at 40 knots, slamming into the starboard side near the bridge and the foremost funnel. The boat rocked violently from the explosion, which tore a gaping 220-foot hole in the outer hull plating.

Passengers and crew scrambled to board lifeboats as the ship listed. A few moments later, a second explosion occurred.

At 2:28 pm, the mighty Lusitania rolled on her side and sank, pulling nearly 1,200 passengers down with her—a casualty list that included 128 Americans.

In his new book, The Day the World Was Shocked: The Lusitania Disaster and Its Influence on the Course of World War I (Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2011, 240 pp., photographs, notes, $29.95, hardcover), Military Heritage contributor John Protasio delivers a powerful narrative that closely examines how the sinking of the luxury liner almost made President Woodrow Wilson’s administration abandon their policy of neutrality and declare war on Germany two years earlier than it did.

The 785-foot Lusitania was the largest ship of the Cunard line. She was impressive vessel indeed. Double the size of the Statue of Liberty, Lusitania had 25 boilers, 192 furnaces, and four propellers that enabled her to reach a top speed of 25 knots, amazing for that era. There were four generating sets, each producing 375 kilowatts of electricity, to provide power to the floating hotel’s galleys, saloons, and pantries. The day she was sunk, Lusitania was carrying nearly 2,000 passengers and crew members.

Three separate courts of inquiry were held after the disaster. Lusitania’s captain, William Thomas Turner, was grilled because he did not follow the British Admiralty’s instructions to zigzag. Turner felt that the speed of Lusitania enabled him to outrun any U-boat, which could only reach speeds of about 15 knots. However, the vessel had six boilers out of commission because some of his crew had left to join the Royal Navy, and she was barely doing 18 knots at the time of the incident. Turner was also accused of disregarding warnings from the German government that it would attack merchant vessels.

Another issue involved Lusitania’s lifeboats. Since the Titanic tragedy three years earlier, maritime law required that there be enough lifeboats for all passengers. But according to one passenger, the lifeboat drill performed onboard was a “pitiable exhibition.” The quick and extreme listing of the ship prevented most passengers from safely boarding the lifeboats; when they did, many of the boats capsized, hurling people into the cold waters of the English Channel.

One haunting question that has lingered over the past 90-plus years is the cause of the second explosion. Initially, it was thought two torpedoes were fired. The German government, however, insisted there was only one. It was also thought that Lusitania was carrying war munitions and Canadian troops. Although she did have 4,200 cases of rifle ammunition and 1,250 crates of reportedly empty shrapnel shells in the hold, the British government steadfastly stated that there were no other military supplies or Canadian troops onboard. In 1993, after months of study, the renowned marine geologist Roger Ballard, who had assisted in the development of unmanned submersibles, concluded that coal dust had ignited and was the source of the mysterious second explosion.

Nonetheless, the sinking of Lusitania and the loss of American lives sparked a huge outcry in the United States. Wilson sent three separate communications to the German government condemning the actions and calling for “strict accountability.” Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who thought the communiqués were too harsh and failed to criticize as well the British blockade of Germany, resigned his post.

In the end, Germany increased its unrestricted submarine warfare and Wilson had no choice but to declare war in 1917. Many experts consider the sinking of Lusitania and the brutal invasion of Belgium to be Germany’s two worst blunders in the conflict. A single torpedo fired on May 7, 1915, would eventually bring about the collapse of the German government and usher in a new era of unrestricted naval warfare.

Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse by Jay Rubenstein, Basic Books, New York, 2011, 448 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, $35, hardcover.

Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse by Jay Rubenstein, Basic Books, New York, 2011, 448 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, $35, hardcover.

Jay Rubenstein, a medieval scholar at the University of Tennessee, has penned a wonderful tale of the First Crusade from ad 1096-1099, when Christian armies traveled to the Holy Land to free it from Muslim invasion. The massive effort began when Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos sent an urgent request to Pope Urban II to help him oust the invading Turks from his homeland. Komnenos’s plea, however, was secondary to the religious zeal of Western nobles and knights who saw the crusade as a way of seizing the hallowed city of Jerusalem and establishing a Christian government.

The author delves into the behind-the-scenes actions that mixed religion and political motives for the arduous trek to defeat the infidels and drive them from the Holy City. Urban delivered a fervent plea at the Council of Clermont detailing atrocities being committed against the defenseless Christians by the pagan Muslim hordes. He also promised that anyone willing to take up arms to defeat the Islamic army would ultimately reap his rewards in heaven.

The People’s Crusade, an untrained and often unruly mob, left Europe with the charismatic Peter the Hermit as its leader. When the crusaders arrived at their first objective, Constantinople, they pillaged and ravaged the countryside, but were easily routed by the Turks when they attacked the city.

The four main bodies of knights and soldiers, trained in warfare, departed next for Europe and took different routes to Constantinople, finally arriving in late fall 1097 to attack the city. The total estimated number in the Christian army was about 35,000. After a series of pitched battles and bloody sieges, the main body laid siege to Jerusalem in 1099. On July 15, they breached the walls and gained entry, slaughtering thousands of men, women, and children in the process.

Many of those who participated in the holy war, and even to those who stayed behind, believed they had witnessed the apocalypse. The horrendous casualties and bloody warfare encouraged them, as Rubenstein writes, “to see in it signs not of an imminent apocalypse, but of an apocalypse fulfilled.”

Second Manassas: Longstreet’s Attack and the Struggle for Chinn Ridge by Scott C. Patchan, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2011, 186 pp., maps, photographs, index, notes, $26.95, hardcover.

Second Manassas: Longstreet’s Attack and the Struggle for Chinn Ridge by Scott C. Patchan, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2011, 186 pp., maps, photographs, index, notes, $26.95, hardcover.

As the author states, there was probably not a more opportune time for General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to crush the Federals than at the Battle of Second Manassas in August 1862. The Confederates did achieve a tremendous victory there, opening the door for Lee’s invasion of Maryland and the subsequent Battle of Antietam less than a month later, but Lee failed to destroy the enemy at Second Manassas, enabling them to reorganize and stop him in Maryland.

Ignoring advice from his commanders, Union Maj. Gen. John Pope positioned the bulk of his infantry in the front of Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s line north of the Warrenton Turnpike, leaving a much smaller force to confront Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s army approaching from the south.

The bloody combat that ensued on Chinn Ridge was some of the worst of the conflict, but the Union soldiers who fought and died there gave the inept Pope enough time to withdraw in good order, preventing an embarrassing rout like the one that had occurred at the First Battle of Bull Run a little more than a year earlier.

In spite of the claim by Confederate Brig. Gen. Dorsey Pender that “there was never such a campaign, not even by Napoleon,” Lee at Second Manassas fell short of the ultimate prize—the annihilation of the Union Army of the Potomac and a possible end to the Civil War.

A Savage Empire: Trappers, Traders, Tribes, and the Wars That Made America by Alan Axelrod, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2011, 336 pp., map, bibliography, $25.99, hardcover.

A Savage Empire: Trappers, Traders, Tribes, and the Wars That Made America by Alan Axelrod, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2011, 336 pp., map, bibliography, $25.99, hardcover.

The author gives a fascinating account of the fur trade from the 17th century to the 1830s, when the most prized animal of the trade, the beaver, almost reached extinction. Although not a graceful or handsome animal, the beaver’s fur was much sought after, not only in America, but in most European countries, to make gentlemen’s hats.

Axelrod begins his book in an interesting manner, writing about the famed English diarist Samuel Pepys, who held his beaver felt hat in high esteem and paid a princely sum for it. It is safe to say that Pepys had no idea, or concern, about how the beaver felt as his hat made its way to Great Britain. Axelrod, however, focuses on the manipulation, broken treaties, greed, and even wars that were fought over the beaver and other natural resources, when certain individuals amassed fortunes from the pelt of the buck-toothed woodlands creature.

The insatiable lust of the trading companies nearly decimated the beaver population by the mid-1830s. The quest for fur drove Americans deeper and deeper into the unexplored western region of the United States, bringing trappers into conflict with the indigenous tribes who occupied the land. Axelrod demonstrates that the story of the American western migration had much do with the fur of one rodent-like creature, the humble beaver.

The Quiet Professional: Major Richard J. Meadows of the U.S. Army Special Forces by Alan Hoe, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 280 pp., maps, photographs, notes, $34.95, hardcover.

The Quiet Professional: Major Richard J. Meadows of the U.S. Army Special Forces by Alan Hoe, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 280 pp., maps, photographs, notes, $34.95, hardcover.

Here is a book about one of the greatest legends in the world of U.S. Army special forces, Major Richard Meadows, a man who accomplished much during his 30-year stint in the military. The recipient of a Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars with “V” device, the Legion of Merit and a host of other decorations, Meadows served with the Special Operations Group in Vietnam and was one of the planners of the Son Tay raid in 1970 to free American POWs from a North Vietnamese detention camp. After his retirement, Meadows traveled to Iran in 1980, posing as a foreign businessman to scrutinize the American Embassy where hostages were being held by the Ayatollah Khomeini’s radical government.

In 1995, just before his death from leukemia, which he believed he contracted from exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, Meadows received the Presidential Citizens Medal. That same year, he was inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame, probably the award he cherished the most. Meadows was a driven man, extremely loyal to his family and the Army. He earned the respect not only of his subordinates, but of his superior officers, all of whom trusted his judgment. He died on July 29, 1995.

The Captain Who Burned His Ships: Captain Thomas Tingey, 1750-1829 by Gordon S. Brown, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 214 pp., bibliography, notes, index, $28.95, hardcover.

The Captain Who Burned His Ships: Captain Thomas Tingey, 1750-1829 by Gordon S. Brown, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 214 pp., bibliography, notes, index, $28.95, hardcover.

This thoughtful book focuses on the man who was the mastermind behind the design and building of the Washington Navy Yard, Captain Thomas Tingey. Originally an officer in the Royal Navy, Tingey switched his allegiance and became an American naval officer, distinguishing himself during the so-called Quasi-War against the French. Tingey led a squadron of ships that patrolled the waters near Cuba, keeping a sharp eye out for French privateers preying on American merchant ships.

In 1800, Tingey traveled to Washington to design and supervise the construction of a navy yard, despite the opposition of many in Congress who saw the buildup of a standing navy as a detriment. Nevertheless, Tingey toiled diligently, completing the site and became the first commandant of the Washington Navy Yard in November 1804, a position he held for nearly 30 years.

With the overwhelming defeat of the American Army at Bladensburg, Maryland, in 1814, the British marched to Washington unopposed and unceremoniously burned the city. Realizing that he could not defend the navy yard, Tingey ordered that the yard and its vessels be destroyed. He was the last officer to leave the navy yard and the first to return after the British had left. Tingey oversaw the rebuilding of the navy yard and continued his service in the U.S. Navy. When he died in 1829, workers at the facility were given a half-day off and flags were lowered to half-staff. As the author writes, Tingey was the kind of man who “would have been pleased if they had raised a glass in his memory, but unhappy had they gone on to drink to excess.”

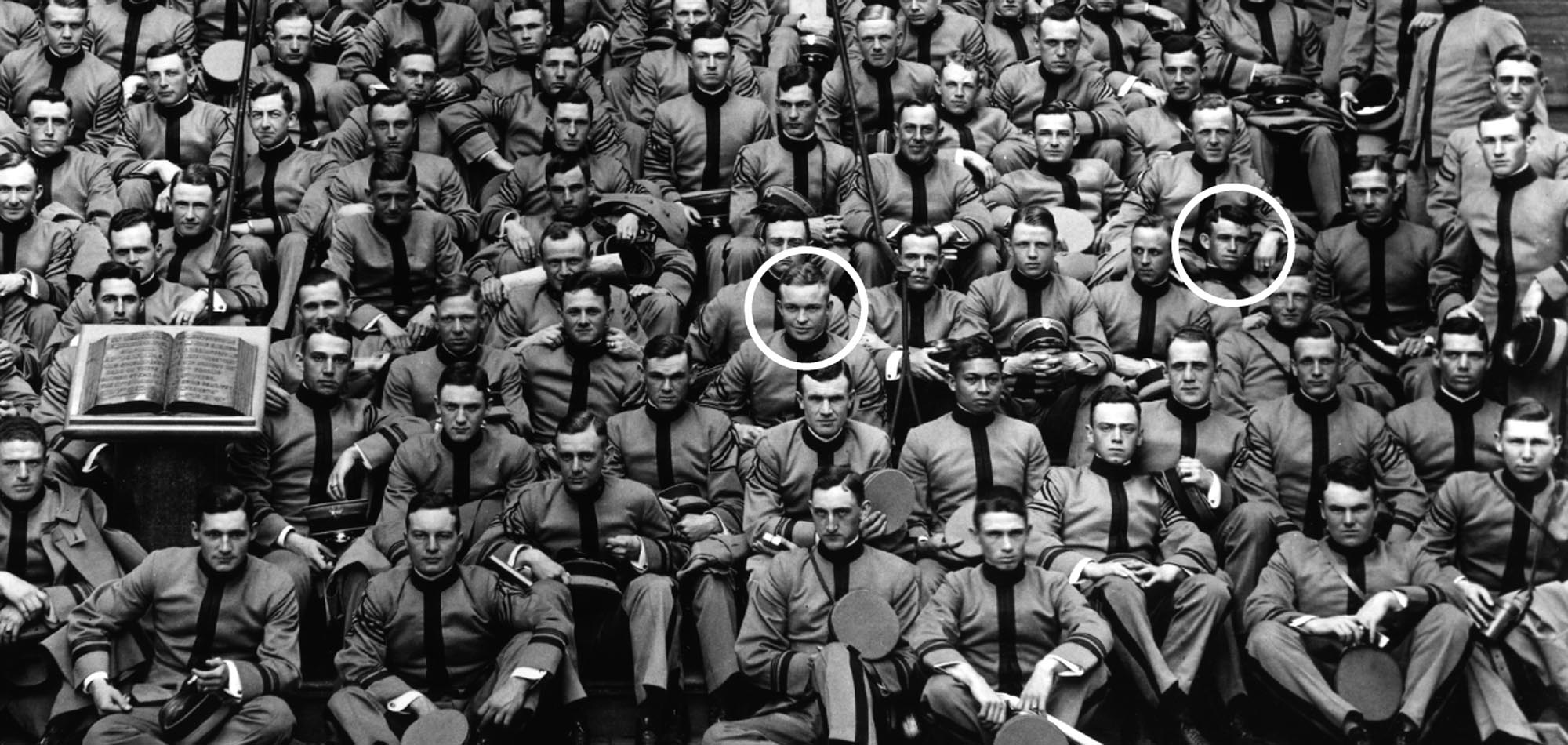

World War I: The American Soldier Experience by Jennifer D. Keene, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2011, 218 pp., map, illustrations, photographs, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover.

World War I: The American Soldier Experience by Jennifer D. Keene, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2011, 218 pp., map, illustrations, photographs, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover.

Trying desperately to remain neutral in a European war that had already taken millions of lives, the United States finally declared war on Germany in the spring of 1917. To meet the demands of such a huge undertaking, General John J. Pershing, leader of the American Expeditionary Force, knew that he needed a large fighting force to meet the requirements of the war. A draft was instituted and the military mushroomed to more than four million men in all branches of the service. Twenty percent of Americans of draft age eventually served in the military.

The author, a professor of history and chair of the department at Chapman University in Orange, California, traces the origins of America’s entry into the conflict, detailing how the army was selected and organized, the battles it took part in, and what became of returning veterans. Pershing’s doughboys were at first scorned by the British and French troops, but eventually proved themselves in battle at Chateau Thierry, Belleau Wood, and the Meuse-Argonne Campaign.

The United States suffered more than 200,000 casualties as a result of the savage combat. “Whether the war illustrated the futility of armed conflict or the heroic endeavors of brave and patriotic men,” Keene writes, “remained a matter of dispute.”

The Rockets’ Red Glare: An Illustrated History of The War of 1812 by Donald R. Hickey & Connie D. Clark, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2011, 234 pp., maps, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

The Rockets’ Red Glare: An Illustrated History of The War of 1812 by Donald R. Hickey & Connie D. Clark, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2011, 234 pp., maps, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

The bicentennial of the War of 1812, often referred to as America’s second war of independence, is fast approaching. Still in its infancy, the United States felt that it had to demonstrate to Great Britain that it was a republic, and not a quasi English colony.

The reasons for entering the war were complex, but the impressment of American merchant seaman by the Royal Navy played an important role in igniting the hostilities. On the high seas, U.S. ships enjoyed great success, but American forces were not so fortunate on land. At one point, the British made their way to Washington, D.C., and burned much of the capital to the ground.

The book is rich with maps and illustrations tracing the origins of the conflict, the major battles and the personalities on both sides. As the authors demonstrate, “the War of 1812 left a lasting imprint on the future.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments