By David Fontaine Mitchell

Following World War II, the British returned to a much different Malaya than they had departed three years earlier. The Empire had first established a presence in the peninsula in 1786 and enjoyed substantial influence over a fairly receptive population until the Japanese invasion of northern Malaya on December 8, 1941. By the 24th they had taken Kuala Lumpur. Singapore subsequently surrendered on February 15, 1942.

Unrest in Malaya

The ensuing three and a half years of Japanese occupation resulted in economic deterioration, dislocation, and racial disharmony within Malaya. Although the British were initially greeted with open arms upon their return in 1945, this feeling quickly diminished. In September 1945, the British Military Administration (BMA) was established as the initial form of postwar government. The BMA, however, was ill equipped and mismanaged, and the British were unable to regain full control of Malaya, resulting in widespread criminal activity nationwide.

The predominantly Malay police force was in shambles, and BMA officers contributed to the nation’s problems by selling arms illegally to local gangs, stealing from civilians, and billeting in private estates. The populace quickly lost faith in Britain’s ability to secure the region. The populace became further disgruntled following the announcement that Japanese currency—which the people had been earning and saving throughout the war—was to be eliminated.

Ethnic tensions exacerbated the state of insecurity on the peninsula. The nation’s ethnic Chinese (which constituted 38.5 percent of the population at the time) lashed out at ethnic Malays (44 percent of the population), many of whom had treated them harshly during the Japanese occupation. The Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), the guerrilla arm of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) that developed following the Japanese occupation, began attacks on certain areas, killing ethnic Malays and taking control of villages.

Malays began to retaliate against the attacks, further intensifying racial conflicts throughout the country. The Malays, who were predominantly Islamic, were wary of the MCP’s professed atheism, which they perceived as a threat. Both ethnic groups became disillusioned with the BMA following the administration’s failure to curb increasing violence.

Following a general strike orchestrated by the MCP on February 15, 1946—the anniversary of Singapore’s fall to the Japanese—the BMA began arresting key MPAJA officials and censoring newspapers, which resulted in greater civil unrest among certain Chinese communities. The British announced the formation of a new civilian government, the Malayan Union. This resulted in widespread criticism from Malays. Under the new government, the sultans, traditionally the administrative and spiritual guides within their respective states, lost much of their authority. This, coupled with the British proposal to include non-Malays in the political process, sparked the formation of the Pan-Malayan Congress, which later became the United Malays National Organization (UMNO).

The new organization protested the Malayan Union, which resulted in abandonment of the just established government in July 1946. A Constitutional Working Committee was formed among UMNO, the government, and various other factions. New proposals were drafted; however, the new government, which became known as the Federation of Malaya, was not proclaimed until February 1, 1948. Many Malayan Chinese and Malayan Indians were outraged with the decision and subsequently protested against the formation of the Federation.

Opposition to the Federation mounted throughout 1947, and many in the Chinese community began to conclude that the British were siding with the Malays. This was particularly insulting to scores of ethnic Chinese who had volunteered to fight with the British against the Japanese. Many of the MPAJA had been trained by the British military in guerrilla warfare tactics and felt betrayed by their former cohorts.

Guerrilla War Breaks Out

In March 1948, the MCP made the official decision to move toward guerrilla warfare as a primary tactic. Violence soon spread throughout the peninsula, which resulted in the declaration of a state of emergency by the British on June 18, following the death of three European plantation managers two days before. The MCP and any organizations that supported their efforts were declared illegal.

The government began to implement a policy of coercion and enforcement, including mass arrests and deportations, to address what they initially believed to be a criminal uprising. This plan ultimately backfired for multiple reasons. For one, the British were applying large-scale conventional tactics that had been successful during World War II to an insurgency. When numerous soldiers were sent into hostile territory to engage in sweeps, they were ambushed in guerrilla hit-and-run attacks.

The short-handed and poorly trained police force (initially consisting of only 9,000 men in a country of roughly five million) further dampened government efforts because they were largely corrupt. Virtually the entire force consisted of ethnic Malays, and many officers, wrongfully perceiving that all Chinese were supportive of the MCP, in turn treated them poorly, which resulted in many neutral individuals joining the Communists.

Numerous Chinese were driven into the Communist camp following the destruction of several villages and huts by government authorities. Security forces, believing a certain individual or community was assisting the MCP, would burn entire areas to the ground, leaving many people homeless and disgruntled. The MCP spread the news of these events to rural areas during their propaganda campaigns, which helped with recruitment and drove many Chinese to believe that the British were just as bad—if not worse—than the Japanese had been.

Tensions continued to rise between the Malay-run state governments and the federal government. The states largely believed the communist uprising to be a federal issue and failed to cooperate with the authorities. Money was also becoming an issue, and the Federation was forced to acquire a loan from London in order to continue its activities. A further blow came after news of the communist victory in China, which the British government subsequently recognized on January 6, 1950.

Perceiving that the communists now had a good chance of succeeding, several Chinese began to support the effort out of fear of retaliation if the guerrillas were to take control. Given that the British were unable to guarantee security to those who denounced the MCP, the government failed to win over much support. The Min Yuen (short for Min Chung Yuen Tung, or People’s Movement) was the primary organization utilized by the party to provide food, information, and supplies to the guerrillas.

The Briggs Plan

In early 1950, following recommendations from the British Defense Coordination Committee (BDCC), a new civilian position was created at the request of High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney and tasked with the coordination of civil, military, and police activities. The new director was 55-year-old Lt. Gen. Sir Harold Briggs, a war veteran who was persuaded to leave his home in Cyprus, where he had been living since his retirement from the service in 1946. Briggs had served in France, Mesopotamia, and Palestine during World War I and had commanded the Fifth Indian Division in Iraq and Burma during World War II, providing him with a firm grasp on jungle warfare.

The new director initially accepted the position for 12 months and traveled to Singapore, where he was briefed prior to arriving in Kuala Lumpur on April 3. Briggs was provided with an executive staff consisting of a civil officer, an army officer, a police officer, an intelligence officer, and the head of emergency services. He spent an entire month touring the peninsula, interacting directly with individuals and organizations at all levels. By the end of May, he had issued a report to the BDCC, which thereafter became known simply as the Briggs Plan.

The long-term proposition focused on securing the populace, decreasing Min Yuen activity, and ultimately eliminating the guerrillas from south to north, one district at a time. To achieve these goals, Briggs wanted to institute regular cross-agency dialogue by setting up routine meetings with the military, police, and civilian administrators. A Federal Joint Intelligence Advisory Committee was established that combined intelligence gathered from every agency—civil, military and police. A Federal War Council was also established and tasked with the oversight and coordination of the campaign, assisted by State and District War Executive Committees. The committees consisted of representatives from the military, police, and government. These committees would meet every morning in what came to be referred to as “morning prayers.”

Briggs went to great lengths to specifically define the roles of the military and the police. The military was to remain subordinate to the civil authorities and assist only when necessary. The police were tasked with law and order and population security, while the military sought out the MRLA in the jungle. Briggs also called for the inclusion of ethnic Chinese in the police force and for their participation in armed patrols, a move that several within the Malay population initially resisted.

The focus had been shifted to winning over the support of the people via a “hearts and minds” approach, and therefore both the military and police were instructed to treat the populace with the utmost respect. The government, however, remained firm, and on June 1 a mandatory death penalty was instituted by law for anyone caught transporting or collecting supplies for the guerrillas.

Resettlement

The primary task instituted by the Briggs Plan was a resettlement policy that targeted Malaya’s massive rural and largely unassimilated Chinese squatter population, which numbered close to half a million. Most of these squatters had fled to the fringes of the jungle during the depression of 1931-1934 and the Japanese occupation and were taking refuge on land owned by the state governments. Briggs concluded that the best way to hinder insurgent activity was to remove their primary source of communication and supplies—the squatter communities.

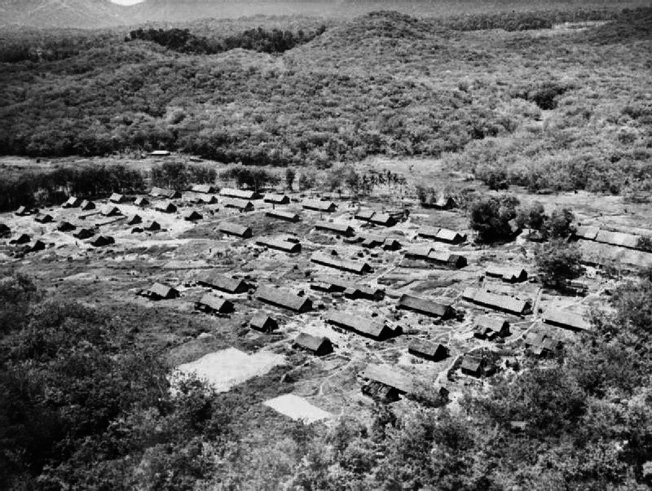

Briggs believed that if the squatters could be cut off from the communist cells, the MRLA would not be able to survive for long in the jungle. Although a resettlement policy had been in place prior to the director’s arrival, it was largely inept and unsuccessful. Briggs centralized the policy in the federal government on June 1, 1950, and drastically altered the results, resettling roughly 385,000 squatters in 480 camps, 80 percent of which were in western Malaya, by the end of 1951.

Under Briggs’s direction, the government began to systematically enforce the resettlement policy. Following the selection of an adequate area of land, troops were sent into the jungle to round up a group of squatters. The men were instructed to be as civil and compassionate as possible, and the troops often would help load the squatters’ belongings onto military vehicles and transport them to their new homes. Families lost all that they could not take with them, as everything left behind was destroyed so that it could not be utilized by the MCP.

The squatters were moved into settlements that were strategically placed in flat, open areas to deter surprise attacks. The compact settlements, surrounded by barbed wire and flood-lights and regularly patrolled by police, were instituted to diminish the Min Yuen supply line and force the guerrillas out of the jungle. The resettlement plan was to be implemented initially in Johore, the state with the largest squatter population, and progressively work its way north in what Briggs described as “rolling the map up on the guerrillas from bottom to top.” However, due to the overwhelming MRLA presence in Johore and the financial support received by the guerrillas from Chinese communities in Singapore, this approach was later abandoned.

The squatter population held mixed opinions on resettlement, but there was surprisingly little opposition. In many instances, they were provided with medical care, running water, electricity, schools, and recreational activities for children, such as the Boy Scouts. Welfare officers, many of whom were young volunteers in their 20s from Australia and New Zealand, were brought in to help with the administration of schools and clinics. Missionaries who had recently been banned from China also volunteered to help in the villages.

Although it varied from settlement to settlement, the average family received a two-week subsistence allowance to build its new home, along with 800 square yards of land and an additional two acres of farmland. The villages were typically located two to six miles from the squatters’ original homes and consisted of an average of 100 to 1,000 people, although a few had upwards of 10,000.

Gates were established in the resettlement camps, which later became known as “New Villages,” and a nightly curfew was implemented from 7 pm to 6 am. The head of each house was required to keep a list of every occupant and instructed by law to notify the police within 24 hours of any arrival or departure. Food was controlled and monitored closely in communal kitchens to inhibit transfer to the guerrillas. Many of the guerrilla units began to go hungry, which led in turn to attacks on their fellow Chinese to obtain food. This greatly damaged the party’s reputation. Starvation drew many MRLA insurgents out of the jungle in search of food and subsequently forced them to engage military and police forces in open warfare.

For many of the rural Malayan Chinese, their experience in the New Villages was the first contact they had ever had with the government. The authorities took advantage of the opportunity and began to teach the younger children about the government in the hope of instilling a sense of national identification. As Briggs stated, “One of the most vital aims throughout the Emergency must be to commit the Chinese to our side, partly by making them feel that Malaya and not Red China is their home.”

Special Branch

Resettlement was only one aspect of curtailing the uprising. The Briggs Plan also restructured and expanded the Special Branch, the intelligence arm of the police that was responsible for gathering and interpreting information. Briggs was concerned about informers selling information to multiple agencies simultaneously and stressed the importance of maintaining one intelligence organization under a single director. Outposts were established throughout the country and instructed to gather as much information on the guerrillas as possible by personal contact with the villagers. Handsome rewards were given to those who provided the Special Branch with information leading to the arrest or death of key guerrilla members. The intelligence campaign was extremely successful, and by the mid-1950s the Special Branch had obtained the names and photographs of virtually every member of the MRLA.

Developing Doctrines For Counterinsurgency Warfare

The start of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, gave an enormous boost to the stagnant Malayan economy. The peninsula’s primary commodities, rubber and tin, were exported in large quantities and as a result there was no shortage of employment within the New Villages. The Chinese squatters who had been resettled were now provided with jobs in these industries. Wages were substantial, and prosperity spread within the communities.

Briggs was also responsible for shifting large-scale conventional tactics to small patrols better suited for counterinsurgency operations. Although not initially well received by many of the brass who had cut their teeth on conventional warfare during World War II, a decentralized, small-unit deep-jungle operational approach ultimately proved successful and remained intact through the end of the war. At the start of this transformation, Briggs stated: “You know, some brigadiers and battalion commanders aren’t going to like what I’m going to tell them—that they won’t be able to use battalions or companies in sweeping movements anymore. They’ll have to reconcile themselves to war being fought by junior commanders down to lance-corporals who will have the responsibility to make decisions on the spot if necessary. We’ve got to look for the communists now, send small patrols after them, harass them. Flexibility of operations in the jungle must be the keynote.”

Although his initiatives were largely successful, Briggs ran into several difficulties during his tenure as director of operations. Following the end of his tour, which had been extended to 18 months, he openly expressed his concerns with the campaign. Briggs recommended that the new high commissioner assume the duties of the director of operations in addition to his executive responsibilities. This resulted in the dual appointment of Lt. Gen. Sir Gerald Templer, a move that would drastically change the course of events in Malaya.

A commanding military officer with a no-nonsense attitude, Templer was personally vetted by Prime Minister Winston Churchill prior to his arrival in Malaya in February 1952. Unlike Briggs, who lacked the executive authority to implement many of his ideas without prior approval and fear of possible appeal, Templer had virtually complete control over the situation. The high commissioner continued and built upon several of the former directors’ initiatives, which greatly increased the overall effectiveness of the campaign.

Although Templer went on to conduct a successful counterinsurgency campaign that ultimately resulted in the defeat of the guerrilla resistance, the framework of the plan was initially established by Briggs. The Briggs Plan transformed the Malayan Emergency by placing an emphasis on small-scale operations, intelligence gathering, and cross-agency communication. His resettlement plan has gone down in history as one of the most effective counterinsurgency initiatives of the 20th century.

It is often said that American policymakers and military strategists fail to learn from history. But as the example of the Vietnam War suggests, it was not for a lack of effort. Komer s report helped propound a myth that emerged by the end of the conflict: that Americans had woefully ignored Britain s secrets to a successful counterinsurgency. But the Malayan Emergency was, in fact, a Cold War obsession, and at the very highest levels.

I’ve often wondered why the Brits were successful in beating back a communist insurgency in Malaya in the 1950s whereas the Americans, with far greater resources brought to bear, were so spectacularly unsuccessful in Vietnam just a few years later. I’ve also wondered what the Brits got out of it at the end of the day. Anybody from Malaya thanking them for their sacrifice on their behalf, anymore than the Greeks are making thanks for their deliverance by the Brits from the Soviet juggernaut just a few years earlier.

Nations don’t have long term friends, only interests.

David.