By Adam Lynch

On Christmas Eve, 1944, Colonel William Holden, commander of the prisoner of war camp at Phoenix, Arizona, suddenly lost all hope for a happy holiday. Early in the evening of December 24, Holden learned that 25 of his German prisoners had somehow escaped! To compound the crisis, no one knew how they got out or how long they had been gone. It was the beginning of what soon became sensational national news and the cause of fear and anger among citizens of the area.

Papago Park Internment Camp, one of 500 POW camps scattered across the United States, covered 3,000 acres, holding over 2,000 German, a few Italian, and even some Japanese prisoners of war. The 400 guards were a mix of Army personnel and civilians. The camp, a former U.S. Army training site, was then several miles outside the Phoenix city limits. Today, urban streets, homes, and apartment buildings cover the space, but senior citizens still talk of the excitement that gripped the area more than 60 years ago.

Escaping the Camp

On Saturday, December 23, the prisoners staged a long, boisterous demonstration. They shouted and sang “Deutschland Uber Alles,” raised a German Navy flag on a weather balloon, and defied orders to bring it down. Ever since news of the massive German Army offensive in the Ardennes Forest, which later became known as the Battle of the Bulge, prisoners had been noisily celebrating. But this Saturday demonstration was staged specifically to divert attention from the escapees.

A head count that morning had been routine. But, as soon as the afternoon head count was finished, one by one, unobserved, the men began climbing down into a narrow underground tunnel that had been four months in the making. Inching along the wet, muddy tunnel while dragging survival packs of food was hard work but, at last, all 25 reached the breakout spot outside the compound fence. They covered the opening and slipped into the night.

The next day, Sunday, Christmas Eve, the camp was quiet as a steady, cold rain fell. There were no work details. Neither roll call nor a morning head count was held. It was an oversight that Colonel Holden would later regret. Later in the afternoon, a head count was made, and it came up short.

Worried guards began frantically looking for missing POWs. Hours went by, and it was not until 7:30 that night, 24 hours after the breakout began, that the ugly truth was confirmed. Twenty-five officers and men were obviously gone!

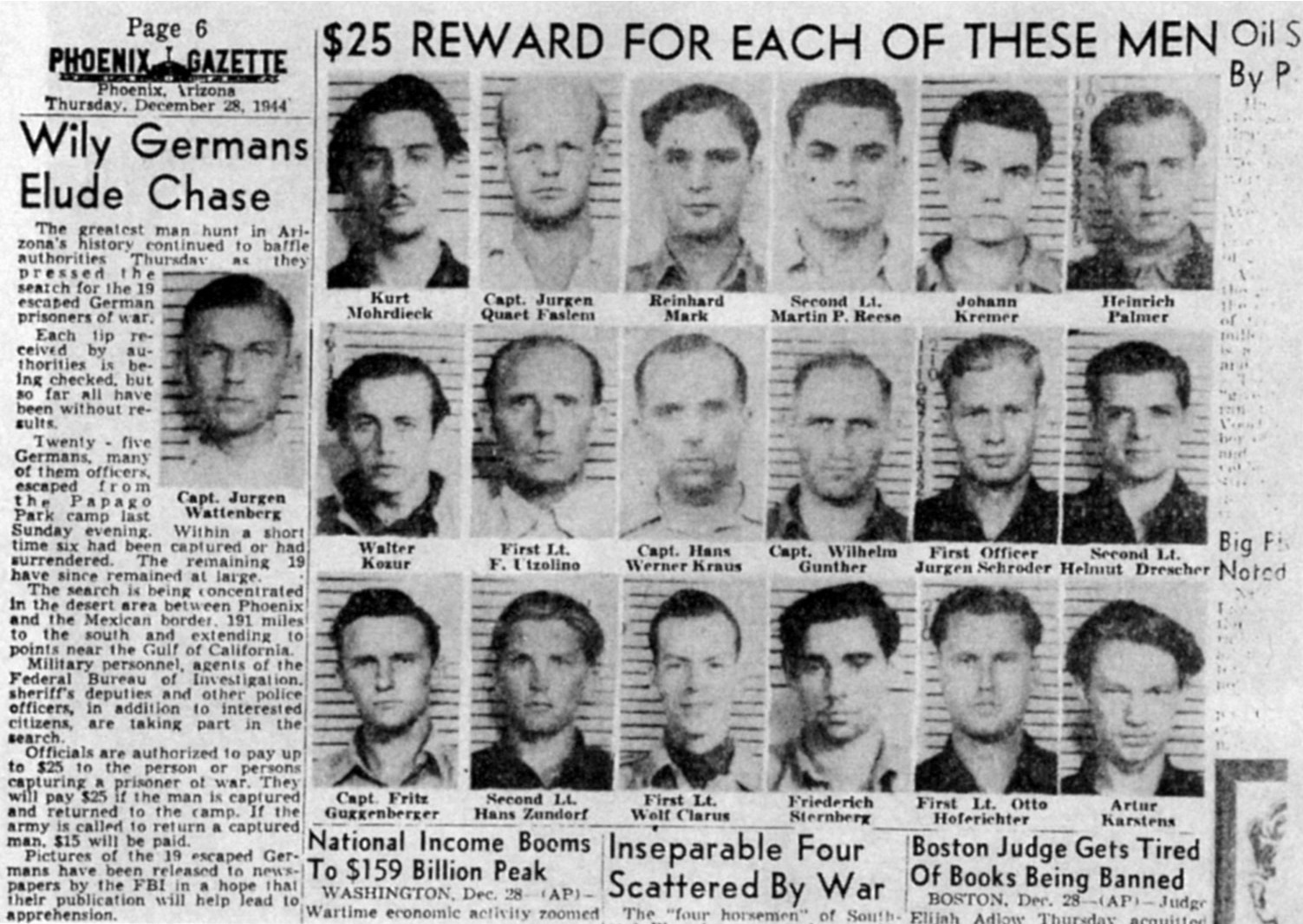

“Wily Germans Elude Chase”

Commander Holden understandably wanted to keep news of the escape quiet until he could learn exactly what had happened, but too many people knew too much. On Monday, Christmas Day, the Arizona Republic and Phoenix Gazette newspapers featured full, front-page coverage of the breakout. In the days to come, headlines such as “Wily Germans Elude Chase” and “Bloodhounds Trailing Nazis” were seen on street corner newsstands all over the Phoenix area.

The Army High Command in Washington, D.C., the Federal Bureau of Investigation, various congressional leaders, and the news media were all posing angry questions Holden could not answer. Network radio commentator Walter Winchell was having a field day with the story in his usual exaggerated style. It was a major Army embarrassment.

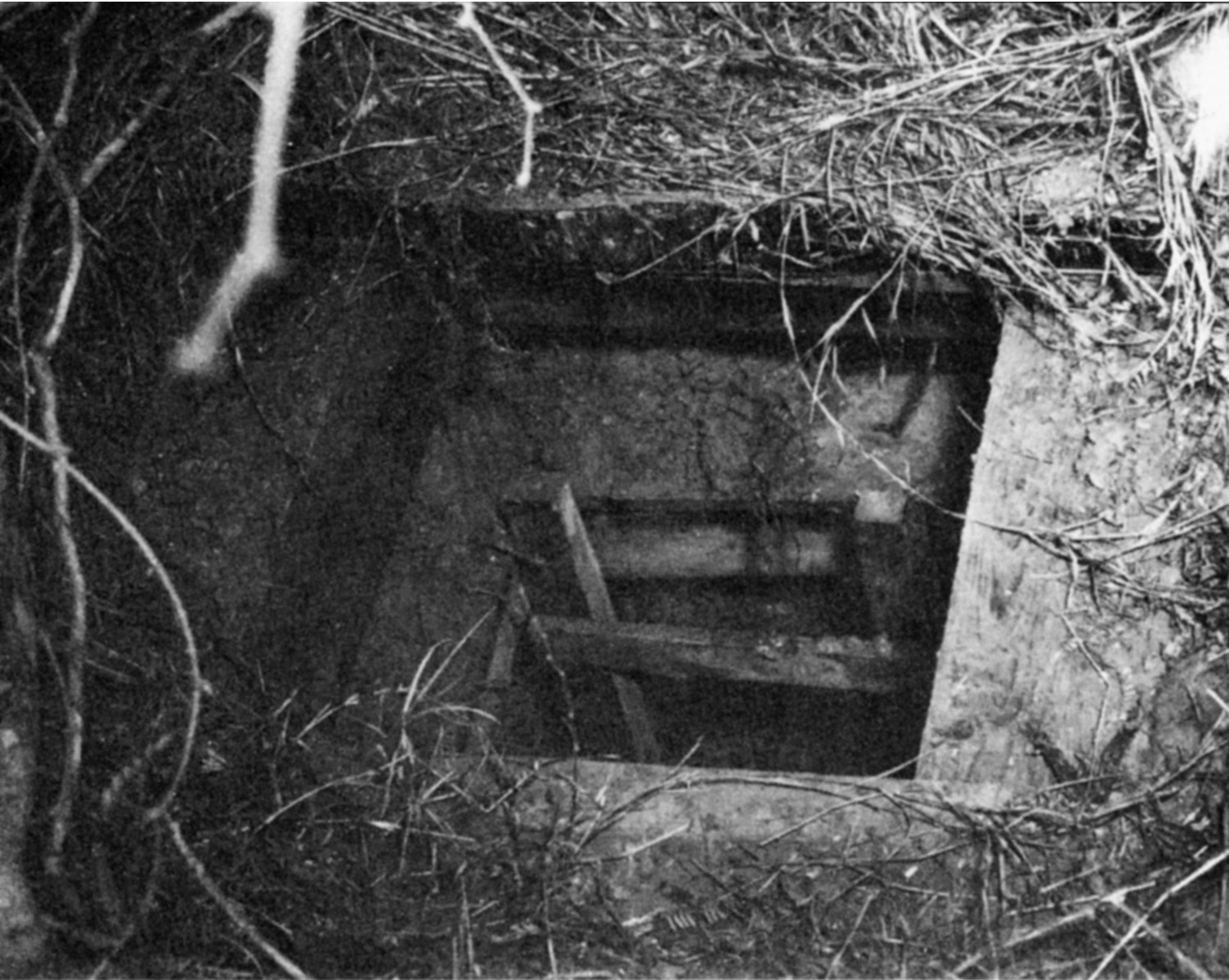

Since he still did not know the truth and there were no holes in the fence, Colonel Holden first told reporters the escapees must have somehow gone up over the eight-foot, barbed wire fence. Even Holden must have known that was an unlikely explanation. Then, the day after Christmas, three days after the breakout, Holden got his second shock. An informer revealed the existence of the 175-foot tunnel. Under the very noses of the guards, it had been dug six feet underground, ending up outside the camp fence, next to the Cross Cut Canal that carried mountain water to the city.

Digging the tunnel had been an amazing feat, requiring the removal of tons of dirt, the rigging of electric lights, and the construction of a cleverly disguised opening. Thousands of dedicated man-hours of digging were required. The men built a shallow square box, filled it with dirt, grass, and weeds, and fit it snugly over the tunnel opening. It was almost invisible. A similar box was made for the other end.

They had started the digging after locating a blind spot between the bath house and the coal box, out of direct sight of any of the guard towers. The exit location was also not in clear view. The planning and construction of the tunnel were in the hands of highly trained officers with engineering experience. How they got the necessary tools and disposed of the dirt was a classic case of deception and imagination.

Captain Wattenber the “Super Nazi”

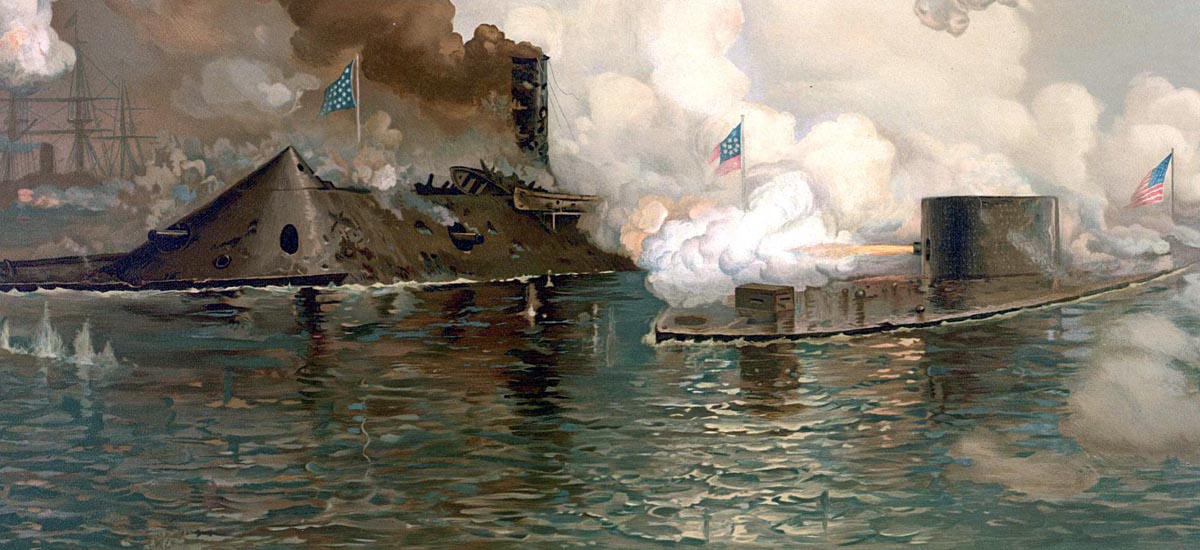

The majority of the German prisoners were former Navy officers and men. Together, they represented a skilled military group dedicated to the German cause. Their recognized leader was Captain Jurgen Wattenberg, 43, one-time skipper of the submarine U-162, which had been sunk in the Caribbean by a British destroyer on December 3, 1942. Ever since coming to the United States as a prisoner, he had been shifted from camp to camp, labeled a “Super Nazi” and a troublemaker. He was joined in the planning by Friedrich Guggenberger, commander of U-513, who was taken prisoner off South America in July 1943, and a third captain, Jurgen Quaet-Faslen of U-595, captured off North Africa in November 1942. Holden placed the trio in compound A-1, a place for men he considered to be disruptive and dangerous. Some of the men in A-1, including Wattenberg, had escaped before.

The arrangement proved perfect for the Germans since it placed those most experienced and prone to escape all in one place. Later, Holden received heavy criticism for that decision, including a scathing editorial in the December 29 edition of the Casa Grande Dispatch that called it a “huge mistake.”

To dig an escape tunnel presented the obvious problem of dirt disposal, but the trio came up with a plan that was both simple and brilliant. They asked for permission to build a “faustball” or volleyball court for exercise. Holden quickly approved the idea, thinking it would keep his most troublesome prisoners occupied. He even agreed to give them tools and equipment and a load of dirt. The Germans could not believe their good luck.

Digging began in August with a six-foot-long vertical shaft sunk down to a tunnel only two and a half to three feet in diameter. The dirt was moved along in a small cart, then brought up to other prisoners who carried it in bags under their clothes out to the faustball court where it was carefully scattered. Other dirt was hidden in barracks or flushed down toilets. For illumination they stole electric wire and light bulbs and simply plugged into a socket in the bath house.

Progress through the desert soil was only a few feet a day. Colonel Holden always assumed the ground was too hard to allow digging a tunnel. He was wrong. When dry, the desert soil was rock hard. However, when wet it could be cut. POWs in other compounds suspected what was happening, but the project remained a secret.

By any standard, security at Papago Park was astonishingly poor. With able-bodied American men off to war, many of the prisoners were employed throughout the area as laborers with work parties, traveling out and back daily to cotton fields, fruit orchards, and farms. The same practice was employed in other states across the country where POW camps were located. The Arizona prisoners were paid 80 cents an hour in scrip, which they used to buy beer and snack foods at the camp. Movies and educational classes were held. Altogether, it was a far better life than risking death in combat. From time to time, prisoners slipped away from work details and remained on the outside for several days before either being caught or returning voluntarily.

Not all who worked on the tunnel chose to leave. Only 12 officers and 13 enlisted men escaped that December night, but they had made elaborate plans and carried chocolate bars, canned milk and meat, cigarettes, coffee, and highway maps with them. They believed that if they could get to Mexico, they had an outside chance of returning to Germany. Later, the lifestyle of the prisoners produced bitter criticism at a time when American prisoners of war were being subjected to extremely harsh treatment in Germany.

Capturing the Former Crewmen

In April that year, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had issued a warning for citizens to be alert for escaped prisoners. His alarm read, “In our midst are nearly 175,000 Axis prisoners of war, trained in the techniques of destruction. I want to warn the civilian population against the potential menace of escaped prisoners of war.” Now, for Phoenix-area residents, this December breakout brought heightened concern.

Incredibly, three of the prisoners had constructed a canvas-covered canoe that could be taken apart and carried in three pieces. After pulling it through the tunnel, they planned to float down the Cross Cut Canal to the Salt River, then to the Gila River and on to the Colorado River to Mexico. State road maps showed Arizona rivers in blue lines, but in truth many of those rivers were often dry. After finding the first river mostly mud, the trio dragged their canoe pieces some 20 more miles trying, and failing, to find sufficient floatable water.

The Arizona Sonoran Desert is an unforgiving environment, and with the cold rain falling, several of the escapees began to have second thoughts about making it to Mexico. On Tuesday, the Arizona Republic headline read, “Storm lashed POWs appearing all around.” Within the first week, eight were back. One by one, and two by two, escapees were spotted hiding in ditches or bushes and were easily apprehended. None offered resistance, and most seemed resigned to abandoning their flight. In one case, two tired, wet, and cold prisoners knocked on the door of a farmhouse, identified themselves, and were actually invited in to share dinner with the family before the police were called to come and get them!

Herbert Fuchs, a 22-year-old U-Boat crewman, hiked to a highway, hitched a ride, and asked the driver to take him to the sheriff’s office. The sheriff called the camp, reporting he had a prisoner who wanted to return. U-boat captains Fritz Guttenberger and Jurgen Quaet-Faslen made it to within 10 miles of Mexico before a border patrolman spotted them sleeping in some bushes. By January 8, only six men were still at large.

Although Hoover’s danger warning was the initial cause for alarm, now area residents were enraged over the quality of food the escapees had with them. One letter to the editor read, “Now, isn’t it a hell of a state of affairs when taxpaying citizens can’t get a single slice of bacon for weeks on end, then read in the paper that prisoners of war can get away with slabs of it?” The December 26 edition of the Tucson Citizen declared, “It’s high time to stop playing sucker to our uninvited guests.”

“The Game is Up and I have Lost”

The capture of the last three fugitives was a combination of high drama and low comedy. Jurgen Wattenberg had crawled out through the muddy tunnel with two of his original crewmen, Walter Kozur and Johann Kremer. The trio found a high overhang next to a desert gully; it provided a cave-like hiding spot where they stayed for almost a month. Wattenberg had devised an ingenious plan. He told one of the men who had remained behind the location of an abandoned vehicle he had once spotted that could be used as a food drop. From time to time, Kremer went to the spot and picked up supplies hidden there by men out on work detail. The trio allegedly went into downtown Phoenix a couple of times just to walk around.

Then Kremer became even bolder. He infiltrated prisoner work crews and returned to camp with them to pick up more food and the latest news of the escape. Later, while out on a work program, he would again sneak away and return to the cave. One day, while inside the prison, he was spotted, identified as an escapee, and detained. The next day, crewman Walter Kozur left the cave to go to the abandoned vehicle, but this time found armed soldiers waiting. Now the leader, Kapitan Jurgen Wattenberg, was the only one of the original 25 still free.

Apparently life on the run in the desert was losing its appeal for Wattenberg as well. Hungry and tired, he hiked into downtown Phoenix, found a restaurant still open, and spent some of his last American money on a bowl of soup and a beer. He stopped at the Adams Hotel and asked for a room. The night clerk reported all rooms taken but suggested something might open in the morning, so Wattenberg fell asleep in a comfortable lobby chair.

Awakening in a few hours, the fugitive noticed the clerk eyeing him suspiciously, so he quickly left. He asked a city street cleaner for directions to the railroad station. That municipal employee, noticing the German accent, alerted a nearby policeman. Sergeant Gilbert Brady of the Phoenix Police Department caught up to Wattenberg, and after a brief, confusing conversation about who he was, where he was from, and where he was going, Brady asked to see Wattenberg’s Selective Service registration card. It was the end of the line for the former U-boat commander. Officer Brady offered Wattenberg a cigarette. After a deep drag, he said simply, “Okay, the game is up and I have lost.”

Aftermath of the Escape

With all the escapees accounted for, the Army began an effort to court-martial Colonel Holden and his top aides for failing to conduct shakedowns, regular compound searches, and proper head counts, but the move was dropped. Not only did authorities worry that trials would prove too embarrassing, but they feared it might jeopardize the vital prisoner work programs all over the country. The Army finally settled for a verdict of dereliction of duty and letters of reprimand. Holden was allowed to retire early for “medical reasons.” The war ended, and by 1946 the last of the POWs had been returned to their homeland.

Over the years, evidence of a POW camp at Papago Park gradually disappeared. The urban sprawl of Phoenix finally consumed the area where the camp once stood. In 1985, a commemorative ceremony was held at the park with the mayors of Phoenix, Tempe, and Scottsdale in attendance. The guest of honor, from the German village of Neustadt-Holstein on the Baltic Sea, was 85-year-old Jurgen Wattenberg.

Great photos. Are any of them public domain? Looking for a few. Thanks