By Blaine Taylor

”The subject of Poland is by far the most complex of all the problems to be considered,” the American delegation to the Paris Peace Conference at Versailles was told in 1919, as it was preparing to sort out the incredible mess in European affairs following the end of World War I.

Indeed, it was. Partitioned, carved up would be a better description, by neighboring Prussia, Russia, and Austria in 1772, again in 1793 (by the first two powers only), and by all three yet a third time during 1795-1796, the once formidable Polish state had ceased to exist by the time of the Napoleonic Wars.

For the next century plus, Polish patriots— from the famous Polish Legions that served in the French emperor’s armies to the Polish troops who fought for both the Allies and the Central Powers during the Great War of 1914-1918—fought to free their nonexistent country from foreign occupiers.

Jozef Kiemens Pilsudski: A Dictator De Facto

Between these colossal, continentwide conflagrations a century apart, ever-resilient, struggling Poles conducted numerous and always brutally suppressed uprisings against their all-time, permanent betes noires, the Russians. Through unceasing warfare, the dream of the Polish eagle, still seen today in the red-and-white national colors, emblazoning a Polish flag flying over a free, united Polish state never died.

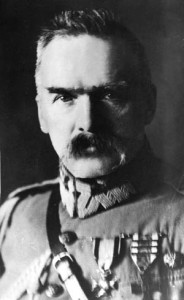

It was into this churning milieu of fierce patriotism that Jozef Kiemens Pilsudski was born in 1867. A native Lithuanian, the nobleborn Pilsudski was the person who, more than anyone else, was responsible for the re-creation of an independent Poland in 1919, when the new Polish state emerged from the Allied postwar deliberations at Versailles.

Pilsudski, whose name today is known to few non-Polish Americans, was a figure of truly epic proportions. His pre-1914 career included being a Socialist editor of an anti-Russian underground newspaper in Warsaw. He forged the modern Polish Army during and after World War I and led it to the greatest victory in Polish history when he defeated the Red Army outside Warsaw in 1920.

Between 1914 and his death at age 68 in 1935, Pilsudski’s titles changed many times— commandant, first marshal, president, chief of state, and minister of war—but always he was the guiding light of Poland’s national life.

Despite the fact that he helped maintain Poland as a democratic republic, Pilsudski was, in actuality, its virtual dictator, especially after 1926, when he launched a successful military coup to overthrow the legally constituted but, in his view, ineffective government.

Like General Dwight D. Eisenhower later, Pilsudski considered himself above politics, and, like France’s Charles de Gaulle, who was an adviser to the embryonic Polish Army during 1920-1921, he haughtily disdained politicians themselves.

Pilsudski was a complex man whose burly-browed, walrus-moustached countenance continued to dominate his associates long after his death and, indeed, until the demise of the Pilsudskiite state itself in 1939. That demise came in a war he knew would someday be started by Adolf Hitler, whom Pilsudski wanted to crush in a preemptive strike soon after the Nazi leader came to office in 1933. But his French allies balked.

The secondary figures during this crucial period in Poland included the marshal’s civilian counterpart in creating the Polish state, the famed, quirky pianist, Ignace Padrewski, and Pilsudski’s ill-fated foreign minister, Colonel Jozef Beck, along with General Eduard Rydz-Smigley, whose post-Pilsudski policies helped destroy Poland a mere 21 years after its tormented rebirth.

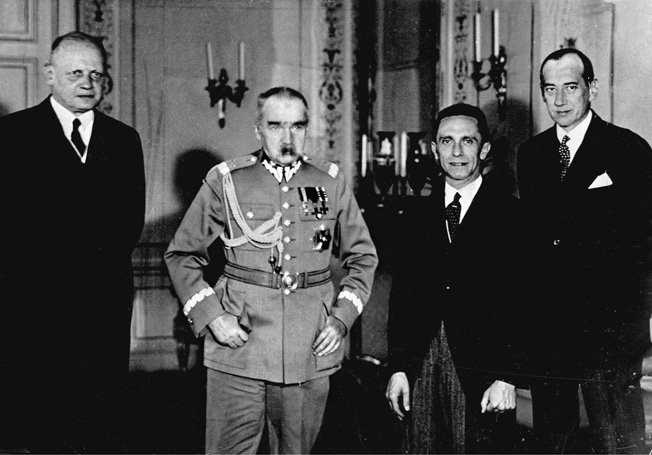

Pilsudski posed with German dignitaries. Shown left to right are: Hans-Adolf von Moltke, German

ambassador to Poland, Pilsudski, Goebbels, and Polish Foreign Minister Jozef Beck.

Collapse of Pilsudski’s Poland

In a very real sense, the newly reconstituted Poland was doomed from its inception. Created out of lands confiscated from the earlier partitionist German and Russian powers, the fate of the new Polish state was constantly in a precarious balance. Beset by enormous domestic problems such as abysmal poverty, lack of land reform, an inexperienced parliamentary system characterized by corruption, and an army based on infantry and Napoleonic-era cavalry, Poland’s existence depended on external factors.

These were a strong alliance with France and Great Britain, both of which militarily deserted Poland in 1939 despite their declarations of war on Hitler; some sort of understanding with the neighboring Versailles-created state of Czechoslovakia (which nevertheless included a dispute over the small, adjoining Duchy of Teschen); and keeping Russia and Germany apart at the end. It was this apparently unlikely German-Russian détente, as formalized in the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939, that wiped out Poland. Quite simply, the Polish eagle was crushed in the Hitler-Stalin nutcracker.

When a new Poland emerged in 1945, the Pilsudskiite eagle was gone forever, and in its place was a communist puppet. During the intervening years, Poland suffered more than any other nation proportionate to its wartime population—Auschwitz, the Warsaw ghetto and uprising revolts, as well as the Katyn Forest massacre mark its tragic tombstones.

In 1939, Hitler offered Colonel Beck an anti-Russian alliance. When the Poles refused, the Führer switched gears and concluded an anti-Polish pact with the Kremlin’s Josef Stalin instead. The rape of Poland followed within a week. All this, though, was in the future during Pilsudksi’s own career, but this was his extended legacy to Poland nonetheless.

A Rabid Nationalist

Pilsudski was first a medical student who became a socialist at age 19, as well as being a rabid Polish nationalist, for which the Russians sent him into exile in Siberia for four years. His escape electrified the Polish masses: a “doctor” entered a psychiatric ward for madmen where the future first marshal was being held, then strolled out with a “friend” in tow. The patient had exchanged his hospital garb for civilian clothes brought in the “doctor’s” medical bag!

The man who would be a chain smoker by age 40 then organized a terrorist group of bank robbers who also freed imprisoned gunmen, and in 1908 he made off with a purloined $100,000. This was used to help finance the creation of a Polish national army during 1910-1912 to fight in the coming general European war, which young Pilsudski accurately predicted would occur.

The first action of this new Polish Legion occurred on August 6, 1914, when Pilsudski staged a coup that left him as the commandant of all Polish forces. Ironically, though, more Poles joined the Russian and German forces in World War I than the official Pilsudskiite legion.

When his troops refused to take a loyalty oath to the German kaiser, Pilsudski was again arrested, but he survived this as well. After 15 months, he was released from prison and returned to Warsaw during the German revolution that overthrew the Hohenzollern dynasty in late 1918. Pilsudski took over supreme power in Poland on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918.

A man always meticulous about his dress, Pilsudski refused to appear in public out of uniform and without a dress sword at his side, much as Hitler refused ever to be photographed in a bathing suit as lacking dignity.

At this time, states author Richard Watt, “Strong, silent, having no close friends but many close followers, Pilsudski enjoyed the respect of practically every Pole. Above all, Pilsudski looked the part of a leader. He invariably wore a plain, gray military uniform without insignia. He was a handsome man of medium height, close-cropped gray hair … and piercing blue-gray eyes. His figure was sturdy without being too heavy … Pilsudski was notably reserved and impenetrable … Pilsudski was indisputably Poland’s greatest military hero.”

Within a week of his arrival, Pilsudski had convinced 80,000 German soldiers to leave Poland peaceably and voluntarily and took power during the period of the typhus and Spanish flu epidemics that swept the country along with the rest of Europe. His grand idea was that Poland would one day be Europe’s premier power, but this was never achieved.

First Marshal of the Polish Army

On April 3, 1920, Jozef Pilsudski was created first marshal of the Polish Army, a title he cherished above all others. That same year, he would defeat Soviet Marshal Semyon Budenny’s Cossacks in the first great military victory since the Battle of Vienna in 1683, and return in triumph to Warsaw, a living legend among his people and throughout Europe.

Hitler was wary of the marshal in 1933, and the following year he concluded his very first non-aggression pact—with Poland. It would last for more than four years after Pilsudski’s death.

By 1923, Poland was the sixth-largest state in Europe, a fact due mainly to Pilsudski’s efforts. The previous year, he had declined to run for the presidency of the Polish republic, despite the fact that he would have won overwhelmingly, as German Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg did in 1925.

“For Pilsudski not to have been elected President would have been considered a national scandal,” notes Watt.

The elected Polish president was assassinated five days after his inauguration, and there were rumors that the first marshal was a target as well. By age 58, the commandant was in retirement. His language was coarse, and he was also susceptible to flattery as a good orator, author, and lecturer. It seemed that there was nothing he could not do, and do well.

Taking the Palace

Pilsudski came out of retirement in 1926 to lead a coup that floundered at a bridge in Warsaw named for the drowned marshal of the Napoleonic Wars, Poniatowski. The first marshal lost his nerve after he was fired upon by troops loyal to the government, but he rallied his forces in time to take over the government’s Belvedere Palace headquarters and so win the day after all.

His wife later wrote, “I was appalled at the change in him. In three days, he had aged 10 years…. Only on one other occasion did I ever see him look so ill, and that was within a few hours of his death.”

In the early 1930s, the first marshal’s health steadily deteriorated; he was a victim of the flu he suffered annually since his youthful exile in Siberia. Still he ruled Poland from the confines of the Belvedere, where he played his endless, but famous, card games of solitaire.

Notes Watt, “Pilsudski now took frequent and lengthy vacations for his health. With a very small entourage, usually only his doctor and an adjutant, he visited Madeira, Rumania, and Egypt. He stayed in rented villas and occupied himself by writing short works on military history. When he was in Warsaw, he no longer attended cabinet meetings. It became increasingly difficult for his subordinates to meet with him….They generally lacked initiative—they were terrified of inadvertently displeasing the marshal. Many of them simply took refuge in craven subservience.”

He was notorious for the abruptness of his governmental appointments. Once he told a summoned general, who found him playing solitaire alone in a massive ballroom of the Belvedere, “Now, then, you will become minister of the interior,” in charge of all the police.

Colonel Beck and the Wicher Affair

One of these appointments was 38-year-old Colonel Jozef Beck as the new Polish foreign minister on November 2, 1932. Pilsudski, like the Pope, felt himself infallible in his judgments and hated all criticism. His appointment of Beck he felt was inspired. The colonel in 1914 had enlisted in the Polish Legion, was interned by the Germans, escaped, and went underground in Ukraine. After the war, he served as an artillery battery commander and then was appointed to the Polish General Staff.

After service as the military attaché in Paris, Beck was sent to the Polish War College, from which he graduated with distinction. As a lieutenant colonel close to the first marshal, Beck played a prominent role in the May 1926 coup d’état and served in the War Ministry and later as Pilsudski’s deputy prime minister in the cabinet. In late 1930, he was sent to the Foreign Ministry as deputy minister before receiving the top post.

This was the man the first marshal had placed in charge of Poland’s foreign affairs, who had to deal with the governments of Hitler and Stalin over the next seven years. Arrogant, he acted superior to the other members of the cabinet and was disliked by many foreign diplomats as well. His appointment, however, was seen to herald a new course in Polish diplomacy, one that had the marshal’s personal stamp of approval.

Typical of the new Pilsudski-Beck approach was the Wicher affair of June 1932, which had been planned and executed by Deputy Foreign Minister Beck with the first marshal’s blessing. A squadron of three British Royal Navy destroyers was set to visit the free city of Danzig (today’s Gdynia) that had been contested by both Germany and Poland since 1919. The incident occurred six months before the Nazis took control of the German government and was designed by Poland to send a message.

The Poles suggested to London that the visit was inopportune. The suggestion was ignored. Pilsudski thereupon ordered the Polish destroyer Wicher to enter Danzig harbor on the day the British squadron arrived. The Wicher was not to request permission from the free city to enter the port, and its captain was to exchange courtesy calls only with the Royal Navy vessels; further, the captain of the Wicher was secretly instructed that, in the event the Polish flag was in any way insulted by Danzigers while he was in the harbor, he was immediately to open fire upon the closest public building.

This didn’t happen, as it turned out, but the visit of the Wicher caused a public furor both in Danzig and in Germany, as Pilsudski intended, with the free city also protesting to the League of Nations that its sovereignty had been violated by her cruise there.

Ironically, it was also at Danzig seven years later that the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein fired the opening salvo of World War II by shelling the Polish fortress of Westerplatte. In the 1980s, the city also spawned the Solidarity movement that eventually overthrew communism in Poland, but this was all in the future as the first marshal entered the last phase of his eventful life.

Pilsudski’s Peculiar Office Hours

Like Hitler later, Pilsudski maintained bizarre working hours, attending to government business from noon to 3 am daily, with even the last constitution of his lifetime tailored to meet his particular needs and habits.

“The Marshal was no longer the person he had been during the Polish-Soviet War in 1920,” noted Watt. “Pilsudski had always loathed detail, despised political conflict, and deeply disliked dealing with people whose duty it was to bring these matters before him. Over the years, the necessity of performing distasteful bureaucratic tasks had made him extremely nervous, impatient, and sometimes very unreasonable. He was not emotionally equipped to deal with the demands of the day-to-day business of government. Pilsudski realized this.”

His office desk was perennially a mess, and the man who had been twice elected president of Poland virtually ignored domestic affairs altogether, interested as he was only in foreign and military matters, such as the buildup of the Polish Army by 1926 to a strength of 300,000 men with 18,000 officers, three times that of Weimar Republican Germany at that time. Fair-minded, Pilsudski refused to purge it of the anti-coup officers that he had defeated that year. His moral authority and public esteem was such that he needed no bodyguards during his later years, and no known assassination was ever attempted, even by his direst enemies.

“An Immense Hole in Polish Political Life”

The Great Depression hit Poland particularly hard, but still the regime overcame it, with a single concentration camp for political prisoners appearing only in 1934, in the final year of Pilsudski’s life. He chose to ignore, not persecute, opponents, unlike his contemporary dictators Hitler, Stalin, and Benito Mussolini.

Asserts Watt, “It goes without saying that Pilsudski’s death tore an immense hole in practically every part of Polish political life,” after he fell victim to a sudden coma on May 12, 1935. “Even though at the time of his death he occupied only two official posts—Minister of War and Inspector General of the Armed Forces— Pilsudski had provided a sort of supreme moral authority that was basic to the organization of the government of independent Poland.

“Regardless of how great or how little a role he played in day-to-day affairs, Pilsudski was the cement that held the whole structure of government together. Now he was gone, and the Polish leaders left behind were devastated.”

Even his greatest real enemy, Hitler, both recognized and publicly acknowledged his foe’s place in history from afar, as noted by German author Max Domarus in his epochal 1992 compilation Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations 1932-45: “In response to the news of Marshal Pilsudski’s death, Hitler sent the following telegram to his widow, Alexandra Pilsudski, on May 13th: ‘The sad news of the decease of your dearly beloved spouse, His Excellency Marshal Pilsudski, has pained me to the quick. I may bid you, my dear madam, and your family accept my offering of deeply felt sympathy. My thoughts of the departed will always be those of gratitude. Adolf Hitler, German Reich Chancellor.’

“[Hermann] Göring was sent to attend the funeral services in Warsaw and Krakau as Hitler’s proxy, while the dictator himself went to a requiem mass held for Pilsudski in the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Hedwig’s in Berlin.”

Destruction Under New Leadership

One of the distraught post-Pilsudski era leaders left behind in Warsaw was his inspector-general of the Army, 49-year-old General Eduard Rydz-Smigley, a Polish peasant born in the former Austrian Galicia. A penniless orphan, he had great charm and an ability to paint and draw. He joined the Polish Legion in World War I and was then designated by the commandant as its leader while Pilsudski languished in German jails. After the war, he held senior commands under the first marshal during the Polish-Soviet War.

Totally uninterested in politics, the pleasant Rydz-Smigley rose to top command mainly through the marshal’s favor, although his peers felt he was an able corps commander but out of his depth as commander in chief of the entire Polish Army in wartime, as proved to be the case in practice against the Germans in September-October 1939.

Following the first marshal’s demise, though, the Polish government built him up as the new Pilsudski, even promoting him to the rank of marshal in peacetime; thus Pilsudski, in effect, continued to run the Polish Army from the grave.

Under Rydz-Smigley’s direction, the Poles expected that they could hold up the Germans in southern Poland until the French and British armies invaded West Germany and together the three forces could defeat Hitler and take Berlin. The Poles even talked of taking Hitler’s capital alone. It was a flawed strategy that failed, and Pilsudski’s Free Poland instead was destroyed, its Jewish population virtually wiped out in the bargain.

Neither Beck nor the marshal survived the war. Rydz-Smigley died of a heart attack in 1941, and Beck died of tuberculosis three years later.

Originally Published October 2010

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments