By Al Hemingway

He was known as Mohammed Ahmed and he was born in 1844 at Dirar, a small island near the Third Cataract of the Nile River, in the Sudanese village of Dongala. He became a religious instructor and embraced a radical sect of Islam known as Wahhabism. It taught that all personal wealth, the worship of holy people, and the “rituals and religious trappings” were bogus and must be forsaken by the truly faithful.

The Mahdi’s followers mushroomed, and soon the son of a Nile shipbuilder had an army of thousands. He felt that he had been chosen by Allah to lead his supporters on a holy mission to cleanse the Islamic faith of all its vices. He declared a jihad, or holy war, to oust the Egyptians and British from the Sudan. Before long, the landscape of the desert would run red with the blood of thousands.

The Mahdi’s followers mushroomed, and soon the son of a Nile shipbuilder had an army of thousands. He felt that he had been chosen by Allah to lead his supporters on a holy mission to cleanse the Islamic faith of all its vices. He declared a jihad, or holy war, to oust the Egyptians and British from the Sudan. Before long, the landscape of the desert would run red with the blood of thousands.

In his new book, The First Jihad: The Battle for Khartoum and the Dawn of Militant Islam (Casemate, Philadelphia, PA, 2006, 256 pp., photos, index, notes, bibliography, $32.95, hardcover), author Daniel Allen Butler takes a close look at the turbulent life of Ahmed, the Mahdi, or Expected One, the long-awaited savior of the Islamic people. Butler also examines the life of the Mahdi’s chief rival during the siege of Khartoum, Maj. Gen. Charles “Chinese” Gordon, one of Great Britain’s legendary military figures. Although they came from entirely different walks of life, the two had a common denominator—both were religious zealots who held firmly to their beliefs with a fierce determination.

Gordon refused to abandon Khartoum, and by April 1884 the city was surrounded and there was no hope of evacuating anyone. The beleaguered garrison held on, and soon Khartoum was the top news in the British press. It became a rallying cry, much like the siege of the Alamo, and the public clamored for the government to come to their countrymen’s aid. The relief expedition, unfortunately, took months to organize. Meanwhile, Gordon was dangerously low on food and ammunition, and morale was nonexistent. To make matters worse, the Mahdi’s men had severed the telegraph line going to Cairo and stopped much of the river traffic on the Nile.

On January 28, 1885, a British relief column finally fought its way through and entered Khartoum, only to discover that the Mahdi’s forces had overrun the city several days earlier. Over 4,000 citizens were slaughtered and all the young boys and girls were taken as slaves. Although he had ordered that no harm come to Gordon, the Mahdi’s overzealous soldiers hacked the general to death on the stairway to the palace and beheaded him. The head was presented to the Mahdi, who overlooked his earlier orders and had the grisly trophy placed on a tree branch “where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above.”

The Mahdi’s life came to an abrupt end in 1885 when he contracted typhus and died. His army was finally defeated at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898 by a British force under the leadership of Lord Horatio Kitchener. A young lieutenant named Winston Churchill took part that day in the final cavalry charge in British history.

Today, the beliefs of the Mahdi live on. Like him, those in the Al Qaeda terrorist organization are Sunni Muslims, and many are devout Wahhabis. They feel, as did the Mahdi, that the Islamic faith has become morally lax and corrupt. His spirit is alive and well in modern terrorist organizations screaming for the blood of the infidels. A new jihad has been proclaimed, and the new Mahdists are making every attempt to see that they are successful. “Only when Islam itself chooses to make a determined effort to purge itself of its modern fanatics and ceases to glorify their spiritual forebears can civilized peoples from every continent hope to live in peace,” writes Butler. “Until then, the ghost of the Mahdi will still haunt the world.”

Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence by A.J. Langguth, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2006, 482 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence by A.J. Langguth, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2006, 482 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain in what has been called America’s second war of independence. Since freeing herself from England’s tyrannical yoke, the newly formed nation had received little respect from her former master. The constant impressment of American sailors to serve aboard His Majesty’s ships, together with ongoing quarrels over the Northwest Territory and other border disputes with Canada, induced President James Madison to lead the young country into conflict with the much-stronger Britons.

The War of 1812 is arguably the least understood conflict in American history. Historian A.J. Langguth does a masterful job of sorting out the primary characters involved in the military and political aspects of the war. From the beginning, little went well for the United States. Despite being fewer in numbers, the Redcoats defeated American forces at various set-piece battles, including Raisin River and Fort Mackinac, and eventually razed Washington, D.C., while Madison and his first lady, Dolley, fled the city mere hours earlier. American troops also bungled several attempts at invading Canada and were soundly defeated along the border between the two countries.

America’s navy, however, delivered impressive victories during the war. Commodore Oliver Perry defeated a British fleet on Lake Erie and was hailed a hero when he delivered his now classic line, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” The USS Constitution outgunned the HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia and earned the nickname of “Old Ironsides” when it appeared as though British cannonballs could not damage to the ship’s oak hull.

Soon the tide of war turned on land for the United States as well when General Andrew Jackson won decisive battles against the pro-British Creek Indians in Alabama. He then defeated a larger enemy army at the Battle of New Orleans and saved the city from an incipient British invasion. Ironically, a peace treaty between the two counties had already been signed, and the bloodshed could have been avoided with better communications from the two capitals to the front.

Union 1812 is an engrossing book. Because of Langguth’s careful attention to detail, the reader comes away with a clearer understanding of a long-forgotten war where America secured her independence once again and earned a newfound respect on the world scene. If not exactly a total victory, the War of 1812 nevertheless established the United States as a proud nation fully capable of defending herself against the mightiest power in the world. It is no coincidence that the two English-speaking nations have not fought each other since.

Ghosts of War: Restless Spirits of Soldiers, Spies and Saboteurs by Jeff Belanger, Career Press, Franklin Lakes, NJ, 2006, 233 pp., index, bibliography, $14.99, softcover.

Ghosts of War: Restless Spirits of Soldiers, Spies and Saboteurs by Jeff Belanger, Career Press, Franklin Lakes, NJ, 2006, 233 pp., index, bibliography, $14.99, softcover.

Do ghosts haunt some of the battle sites around the world? Author Jeff Belanger gives convincing, if not necessarily conclusive, evidence in his new book that restless spirits still walk among us. Combining his love of history and the supernatural, the author has amassed a collection of stories concentrating on some of the battlefields and dwellings supposedly visited by ghostly specters who participated in historic events at the locations.

The story about the Alamo is the most intriguing. Everyone knows that nearly 200 defenders of the old mission were slaughtered to the man by the Mexican Army under General Santa Anna in March 1836. Park rangers who provide security for the building have professed to seeing the apparition of a Mexican soldier at the site. Also, the ghost of what appears to be a Texan has been spotted as well. (No Tennesseans seem to have made a reappearance, although David Crockett and his volunteers comprised a strong contingent of defenders at the Alamo—something many Texans conveniently forget.)

From the Ottoman Wars of the 14th century to the present-day fighting in Bosnia, Belanger’s vignettes will send chills up and down your spine. There are certainly more than enough battles to supply restless ghosts by the regiment.

The Highway War: A Marine Company Commander in Iraq by Major Seth W.B. Folsom, USMC, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2006, 426 pp., photos, maps, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Highway War: A Marine Company Commander in Iraq by Major Seth W.B. Folsom, USMC, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2006, 426 pp., photos, maps, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Since the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, there have been numerous firsthand accounts by individuals who have served there. The main reason why Marine Major Seth Folsom’s story is so fascinating is that he kept a day-to-day diary of events. The entries in his “battered notebook” give his book a gritty realism. It is filled with comprehensive details of his tour of duty in that needlessly wartorn country and how he dealt with the daily strain of combat.

Folsom was the commander of Delta Company, 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division. His LAR unit was at the vanguard of the invasion of Iraq and provided timely information to RCT-5 (Regimental Combat Team) during the drive on Baghdad.

The author’s journal provides insight into the tremendous responsibility of leading men into battle. The stress of ordering men into harm’s way that cannot be overstated. Folsom rises to the challenge, despite his inner fears, and emerges a better man for it. “The burden I had carried on my shoulders for so long was finally lifted,” he observes. “I realized that whatever it was I had carried back with me had been left behind somewhere in the swirling wind and shifting sands of Iraq.”

50 Military Leaders Who Changed the World by William Weir, Career Press, Franklin Lakes, NJ, 2007, 259 pp., illustrations, index, $24.99, hardcover.

50 Military Leaders Who Changed the World by William Weir, Career Press, Franklin Lakes, NJ, 2007, 259 pp., illustrations, index, $24.99, hardcover.

Author William Weir has undertaken a monumental task, selecting 50 military leaders that have made an impact upon world history. Besides well-known figures such as George Washington, Genghis Khan, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Ulysses S. Grant, he also spotlights some of the lesser-known individuals who have made important military contributions that have altered the course of historic events.

One such character was Maurice of Nassau, who was born in 1567 and died in 1625. After the death of his father during a revolt in the Netherlands, Maurice took command and performed admirably despite his young age. In addition to his military skills, Maurice was an innovative organizer of his army. He divided his men into battalions, companies, and platoons and developed a clear chain of command that vastly improved communications. He also restructured his battle formations so that his musketeers could fire their weapons, then step back to reload while the next rank of riflemen moved forward to discharge their muskets. This procedure allowed his men to pour continuous fire into the enemy ranks. These imaginative developments have withstood the test of time, and some are still in use today.

My Father IL Duce: A Memoir by Mussolini’s Son by Romano Mussolini, Kales Press, 2006, 163 pp., illustrations, $27.95, hardcover.

My Father IL Duce: A Memoir by Mussolini’s Son by Romano Mussolini, Kales Press, 2006, 163 pp., illustrations, $27.95, hardcover.

Romano Mussolini was an accomplished jazz musician during his lifetime. Before his death, he penned his memoirs, describing what it was like growing up as the son of Benito Mussolini, the ill-fated leader of fascist Italy during World War II. Despite his father’s bungled attempt at leading Italy during the war and his ultimate inglorious demise (he was shot, along with his mistress, as a traitor, then strung up like a side of beef from a pole), Romano Mussolini wrote a poignant book that reflected a son’s undying love for his father.

The reader should beware, however, as some of the younger Mussolini’s observations about world events during that turbulent period in history are grossly inaccurate. As historian Alexander Stille writes in his introduction to the book, “While Romano’s narration of historical facts is highly suspect and often flat-out wrong, the feelings of filial affection and love are real and entirely comprehensible.”

In spite of his shortcomings as a historian, Romano Mussolini’s book is a good place to start for anyone desiring to learn more about the private life of Il Duce, in all his vainglorious glory.

Aviation Century: War & Peace in the Air by Ron Dick & Dan Patterson, The Boston Mills Press, 2006, 352 pp., illustrations, $49.95, hardcover.

Aviation Century: War & Peace in the Air by Ron Dick & Dan Patterson, The Boston Mills Press, 2006, 352 pp., illustrations, $49.95, hardcover.

Ever since the Wright brothers recorded mankind’s first epochal flight on the sandy beaches of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, over 100 years ago, man has continually reached for the stars. This is the fifth and final book in a series that commemorates how that earth-shattering event and subsequent flights have reshaped the modern world.

The authors discuss the various aircraft, their designs, and the talented pilots who have flown them. This coffee table book is rich with numerous photographs depicting the course aviation history has traveled through the past century.

“Forewords rarely provide investment advice,” writes Walter Boyne, former director of the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, “but a canny investor might just buy four or five sets of these books, get them autographed, and then put them away as a nest egg for his or her grandchildren. They are that good.”

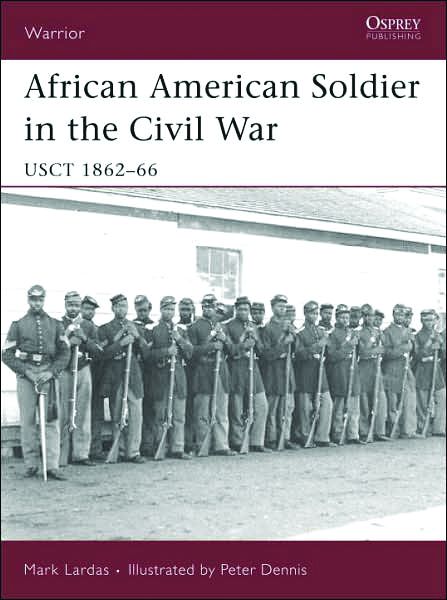

African American Soldier in the Civil War, USCT 1862-66 by Mark Lardas, Osprey Publishing, 2007, 64 pp., illustrations, $17.95, softcover.

African American Soldier in the Civil War, USCT 1862-66 by Mark Lardas, Osprey Publishing, 2007, 64 pp., illustrations, $17.95, softcover.

At the outset of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to bring an end to the rebellion. Inspired by the promise that the conflict would put an end to slavery, many free blacks attempted to enlist in the Union Army. At first they were denied. As the war dragged on, however, the Lincoln administration realized that the large pool of black recruits could prove beneficial to the war effort.

Black units sprang up, and soon the United States Colored Troops were fighting in all theaters of the war. The book traces the discrimination, from both Northern and Southern soldiers, that the black troops had to tolerate until they could prove themselves in battle. After units such as the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry behaved gallantly under fire at Fort Wagner, South Carolina, the black soldier began to gain a newfound respect from his fellow comrades.

This book is full of wonderfully detailed color prints and rare photographs depicting life as a soldier in a black unit during the Civil War. Osprey Publishing has produced another little gem for anyone interested in this divisive and convulsive period of American history.

Argonne Days in World War I by Horace Baker, edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, 2007, 184 pp., illustrations, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Argonne Days in World War I by Horace Baker, edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, 2007, 184 pp., illustrations, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Although the strategy for the Meuse-Argonne campaign looked fine on paper, the overall results were dismal. Attempting to sever the German supply lines, the American Expeditionary Force ran headlong into a determined enemy willing to fight to the death. The offensive mercifully ended when the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.

Private Harold Baker kept a journal of his time with Company M, 128th Infantry, 32nd Infantry Division, beginning in September 1918. Reminiscent of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, Baker’s diary relays the fears and trepidations of the common foot soldier during the bloody Meuse-Argonne campaign.

Baker expanded on his notes immediately after the war and wrote a full account of his experiences as a Doughboy. It was first published in 1927, but few copies survived. Eventually, one copy was discovered in the University of Michigan library. Luckily, it is now being reissued so that everyone can read about the near-death experiences men like Baker had to endure while serving on the Western Front in the Great War.

One Day in History: July 4, 1776 edited by Dr. Rodney P. Carlisle, HarperCollins/Smithsonian, 2006, 272 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

One Day in History: July 4, 1776 edited by Dr. Rodney P. Carlisle, HarperCollins/Smithsonian, 2006, 272 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Probably no other day in American history was more important than July 4, 1776. On that day the newly formed Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence authored by the young man from Virginia, Thomas Jefferson. When this document was ratified, it started the United States of America on the long road to freedom from Great Britain that would culminate at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

This book is first in a series of “individual encyclopedias” designed to explain crucial dates that helped form our country into the nation she has become today. Various authors have compiled 100 short essays to include background into the people, places, and events on pivotal days in American history.

Included in the book are over 250 photographs to accompany the text, touching upon Revolutionary War commanders and leaders, commerce and trade, Independence Hall, the contributions of the individual states to the war effort, and England’s reaction and subsequent strategy to regain her colonies, to name just a few topics.

AK-47: The Weapon That Changed the Face of War by Larry Kahaner, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007, 258 pp., illustrations, index, $25.95, hardcover.

AK-47: The Weapon That Changed the Face of War by Larry Kahaner, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007, 258 pp., illustrations, index, $25.95, hardcover.

While Russian soldier Mikhail Timofeevich Kalashnikov was recuperating from wounds suffered during World War II, he drew a model for a simple assault rifle that could be operated in any climate with minimal service. He didn’t realize at the time that he would revolutionize warfare with his simple concept.

What emerged was the Avtomat (Automatic) Kalashnikov 1947, or AK-47. The weapon is the favorite of every army and terrorist group in the world today. It has been in every conflict worldwide since the end of World War II. There are an estimated 75 million of the weapons in use today.

From the rice paddies of Vietnam to the cities of Iraq, the American fighting man has had to listen to the distinctive sound of the AK-47 for the past 40 years. It is one of the most reliable rifles ever manufactured because it rarely jams and can use “imperfect ammunition.” It has been dubbed the “$10 weapon of mass destruction,” and as Kahaner states, “It has shifted the balance of power in warfare by allowing small determined factions, not just armies, to overthrow entire governments.”

Stalkers and Shooters: A History of Snipers by Kevin Dockery, Berkley Publishing Group, 2006, 372 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Stalkers and Shooters: A History of Snipers by Kevin Dockery, Berkley Publishing Group, 2006, 372 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Ever since warfare first began, men have hidden behind rocks and trees to take aim at their adversaries and kill them in battle. Everything from the bow and arrow, to the musket, to the modern-day M21 rifle has been used by the sniper to eliminate the enemy. In modern times, sniping has evolved into a science—a science with deadly, effective results.

Every branch of the service has a cadre of well-trained snipers. Using his ability to quietly position himself, the sniper can deliver nerve-wracking fear to any soldier on the battlefield. Such was the case of Carlos Hathcock, a Marine sniper who served in Vietnam and amassed an incredible 93 confirmed kills during his tour of duty. Hathcock was so proficient the enemy had a price on his head. His exploits during the war are still legendary.

Author Kevin Dockery tells Hathcock’s story and also traces the roots of snipers in the field of law enforcement. He has gathered some fascinating firsthand accounts from snipers in both the civilian and military communities to further delineate the shadowy and deadly world of the trained marksman and manhunter.

The Crash of Little Eva: The Ultimate World War II Survivor Story by Barry Ralph, Pelican Publishing Company, 2006, 209 pp., illustrations, index, $16.95, softcover.

The Crash of Little Eva: The Ultimate World War II Survivor Story by Barry Ralph, Pelican Publishing Company, 2006, 209 pp., illustrations, index, $16.95, softcover.

On December 3, 1942, a B-24D Liberator named “Little Eva” from the 321st Bomber Squadron, 90th Bomber Group, encountered a tropical storm while returning from a bombing mission over Buna, New Guinea. Veering off course, the aircraft eventually began to run out of fuel, and the crew members had no choice but to bail out. In the end, only three would survive their terrible ordeal in the rugged Australian Outback.

The pilot, 1st Lt. Norman Crosson, and his crewmate, Lt. John Wilson, were rescued nearly two weeks later as they were making their way to Escott Station, an old cattle ranch that stretched for nearly 250,000 acres. Staff Sergeant Grady Gaston, the other surviving crewman, was picked up in a hut on Seven Emus Station, a homestead that covered over 750 square miles, over three months later. He could barely stand and weighed a mere 80 pounds. His hair had turned completely gray.

The Crash of Little Eva is an astonishing adventure tale. It also demonstrates the tenacity of the human spirit to withstand any test, no matter how harrowing, in order to survive.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments