By Christopher Miskimon

While most of the focus on World War II’s beginning centers on Europe and Nazi Germany’s rise, there is also a distinct body of writers and researchers who have turned their gaze eastward toward Asia in the 1930s. Much of this work looks at the rise of the Japanese Empire, its war with China, and how various incidents in East Asia influenced the Pacific War of the 1940s. There has been little real effort to show how events in Asia may have influenced what was happening elsewhere. Stuart Goldman’s Nomonhan, 1939: The Red Army’s Victory that Shaped World War II (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 226 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.00, hardcover) aims to do just that, making a coherent argument that a battle still little known in the West had a dramatic and possible history-altering effect on the invasion of Poland in September 1939.

In 1939, the small village of Nomonhan sat in the border zone between Japanese-controlled Manchuria (Manchukuo) and Soviet-dominated Mongolia. The actual border was in dispute; for the Soviets, it ran near the village itself while Japan placed it several miles to the west along the Halha River. The actual area had little in it to justify fighting, and during the early 1930s the Soviets stayed mainly on the defensive and tried not to provoke the Japanese because the Red Army was still relatively weak and unprepared.

In 1939, the small village of Nomonhan sat in the border zone between Japanese-controlled Manchuria (Manchukuo) and Soviet-dominated Mongolia. The actual border was in dispute; for the Soviets, it ran near the village itself while Japan placed it several miles to the west along the Halha River. The actual area had little in it to justify fighting, and during the early 1930s the Soviets stayed mainly on the defensive and tried not to provoke the Japanese because the Red Army was still relatively weak and unprepared.

The Soviet opponent in Manchukuo, Japan’s Kwantung Army, was considered an elite formation in the emperor’s military. It also operated virtually independently of higher authority, even using political and cultural maneuvering to disregard orders from Tokyo when it suited the Kwantung commanders. Many on the Kwantung Army staff assumed there would eventually be war between Japan and the Soviet Union and took a hard stance toward border incidents.

By the late 1930s, however, the Red Army had made great improvements in its equipment and organization, despite the crippling effects of Premier Josef Stalin’s purges of its officer corps. The Soviets were ready to assert their rights in the Far East using a force that was larger and better equipped with armor and artillery than the force the Kwantung Army could field. As would become painfully evident later against the Allies, Japan could not produce modern weaponry in sufficient quantity and instead tried to imbue its soldiers with an aggressive, superior “spirit” which would allow them to overcome any impediment. This belief in their moral supremacy paired with the Kwantung Army’s arrogance caused a fatal underestimation of Soviet capabilities.

The stage was set when a skirmish between Mongolian and Manchukuoan cavalry occurred near tiny Nomonhan in May 1939. Both sides decided it was time to teach a lesson. The actual fighting spanned the next several months until the end of August. While the Japanese enjoyed some initial success, they were unaware of a methodical, deliberate Soviet buildup under the leadership of General Georgi Zhukov. In August, the Red Army struck with a massive combined arms offensive, which gradually crumbled the Japanese defenses and threw them out of the disputed area. Once the Soviet troops had succeeded in expelling the Japanese from what they considered Mongolian territory, they stopped, and a startled Japanese government quickly signed a cease-fire.

Aside from a detailed telling of the actual battle, the book explains the political machinations and their wide-ranging effects on various nations. Stalin, fearing a two-front war, had his diplomats negotiating with Germany, Great Britain, and other European nations in an effort to play each off the other by alternately hinting at alliances or treaties. While none of them favored the Soviet Union, the communist nation was too large to be ignored, and this had to be dealt with at some level.

Right up to the weeks before World War II began, Stalin feared a Japanese invasion of the Soviet Union in the Far East. With the crushing victory at Nomonhan, this threat was effectively erased, allowing Stalin to return his focus to Europe, where Hitler’s Wehrmacht stood just days from crossing the Polish border and the Soviets prepared to take their share. This was possible because Soviet espionage efforts confirmed the Japanese were no longer considering war against them.

Instead, the Japanese leadership decided to turn toward the Pacific to seize the resources the nation needed to sustain itself. This led to eventual war with the United States and allowed the Soviet Union to transfer much of its eastern military might to Moscow in time to defeat the German invasion that came in 1941. While there may be argument about how influential Nomonhan was to the larger war, this book makes a cogent argument of its profound effect on the course of history.

World War II required the production of matériel on a scale surpassing anything yet seen in human history. For the Allies, the United States provided the bulk of not only weapons, but also trucks, ships of all types, and items down to radios and raw materials. A Call to Arms (Maury Klein, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013, 866 pp., notes, bibliography, $40.00, hardcover) gives the detailed story of how America became the “Arsenal of Democracy.”

World War II required the production of matériel on a scale surpassing anything yet seen in human history. For the Allies, the United States provided the bulk of not only weapons, but also trucks, ships of all types, and items down to radios and raw materials. A Call to Arms (Maury Klein, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013, 866 pp., notes, bibliography, $40.00, hardcover) gives the detailed story of how America became the “Arsenal of Democracy.”

That fact that the nation could do so was not seen by everyone. After a decade of depression and isolationism, America was woefully unprepared to equip its own forces, much less those of its allies. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Congress he wanted to set aircraft production goals at 50,000 planes a year, he was ridiculed. Nevertheless, within a few years American factories were turning out an amazing and diverse quantity of products for the war effort. By 1945, the 50,000-plane goal had been handily exceeded; 325,000 aircraft had rolled off the production lines. Agricultural output and raw material extraction likewise skyrocketed.

Along the way, the author, an economic historian, attempts to revise the wide belief that on December 8, 1941, America smoothly and easily slipped onto a war footing. The path to increased production and military expansion was a difficult one, which caused considerable social upheaval as women found new roles in society and minority populations, such as African Americans in the American South, moved to other regions to find work. Professor Klein also challenges the myth of the “Greatest Generation,” claiming those who fought in World War II acted because they were forced to do so by circumstances rather than any innate superiority to Americans of other eras.

Once production got under way, it had to keep up with change. For example, when the riveted armor on tanks was proved defective on the battlefield in North Africa, manufacturers realized the need to switch to welded armor. This change went more smoothly than the old annual changes for new car models before the war. Companies constantly devised new and more efficient ways to produce, setting themselves up for the postwar economic boom.

The highlights of many air shows are flight demonstrations by World War II fighters and bombers. Few of them fly today, and the chance to see and hear a North American P-51 Mustang or Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress actually in the air is exciting indeed. Hidden Warbirds: The Epic Stories of Finding, Recovering and Rebuilding WWII’s Lost Aircraft (Nicholas A. Veronico, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2013, 256 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $30.00, hardcover) reveals how private collectors and restoration companies search the globe for the remains of World War II’s aviation heritage.

The highlights of many air shows are flight demonstrations by World War II fighters and bombers. Few of them fly today, and the chance to see and hear a North American P-51 Mustang or Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress actually in the air is exciting indeed. Hidden Warbirds: The Epic Stories of Finding, Recovering and Rebuilding WWII’s Lost Aircraft (Nicholas A. Veronico, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2013, 256 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $30.00, hardcover) reveals how private collectors and restoration companies search the globe for the remains of World War II’s aviation heritage.

Thousands of planes were built during the war, 325,000 in the United States alone. During the war some crashed; after the war others were abandoned or mothballed until they were sold for scrap. A few went to museums or were sold to private pilots as racing planes, tankers, and fire bombers. Many went to foreign militaries in South America and elsewhere. Over time, they started to disappear altogether.

At that point a small number of private citizens, a few specialist businesses, and museums began trying to gather what was left for preservation. A lucky few aircraft sat in the weeds around various airfields in the United States. Others sat in swamps, or were buried in glaciers or submerged in lakes and seas worldwide. It is an ongoing effort to collect what remains, particularly rare aircraft. This book chronicles those efforts and is geared toward aviation enthusiasts in particular, who will appreciate the stories of individual aircraft and the history behind them.

Take, for example, the B-17E named Swamp Ghost. This plane arrived at Hickam Field, Hawaii, 10 days after Pearl Harbor and later flew to Australia. On February 22, 1942, the bomber was sent on a mission against the Japanese base at Rabaul. Attacked and damaged by defending Japanese Zero fighters, fuel leaks caused the crew to belly land the B-17 in a swamp on New Guinea. The crew survived and spent four days walking the eight miles to Gumbire Village. Malaria stricken, the crew embarked on a perilous journey back to Australia, arriving on March 30.

Three decades later, an Australian Air Force helicopter crew on a training mission saw the bomber’s tailfin poking up through the tall Kunai grass. Landing to investigate, the crew found the abandoned bomber with coffee still in the crew’s flasks and the machine guns still loaded. Over the next few years the plane was revisited, disarmed, and partially stripped of equipment. Eventually, an enthusiast recovered the plane, and it now sits in Hawaii, awaiting display in a museum.

The end of the war in Europe is often neatly summarized into a few key events: the liberations of the concentrations camps, Hitler’s suicide, and the Nazi collapse. In reality, it was an extremely complex and chaotic period full of tiny details. The advancing Americans might seize a dozen villages without a shot fired only to enter a vicious firefight against diehard fanatics at the next. Would a given German unit fight or was it ready to surrender and end the bloodshed?

The end of the war in Europe is often neatly summarized into a few key events: the liberations of the concentrations camps, Hitler’s suicide, and the Nazi collapse. In reality, it was an extremely complex and chaotic period full of tiny details. The advancing Americans might seize a dozen villages without a shot fired only to enter a vicious firefight against diehard fanatics at the next. Would a given German unit fight or was it ready to surrender and end the bloodshed?

Thus the scene is set for The Last Battle (Stephen Harding, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2013, 233 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $25.99, hardcover), a rescue mission to save imprisoned French politicians. It was an unlikely enterprise involving GIs, slave laborers, SS troops, and finally German Army soldiers … on both sides.

After the conquest of France, the Third Reich imprisoned a number of important French leaders, among them former premier Edouard Daladier and General Maurice Gamelin, who had been sacked in May 1940 after his response to the Nazi invasion failed. Among others, they were in time sent to the Schloss Itter, a castle in northern Austria run by the SS as a prison for VIPs the Nazi regime might later need. While prisoners, their time was relatively safe and comfortable.

By the first days of May 1945, their situation became much less certain. The Reich was crumbling and the prisoners wondered whether they awaited liberation by the Allies or execution by SS thugs intent on hiding their crimes. A few went to find the approaching Allies along with a German officer who had decided his war was over. He ran into Captain John Lee of the 12th Armored Division, who set out to rescue the imperiled Frenchmen.

Along the way, Lee and his small task force would find strange partners, among them the almost unknown Austrian resistance and a group of German soldiers who threw their lot in to protect the French prisoners. Arriving at the castle, the rescuers found themselves surrounded by SS troops intent on taking it, ending in a finale worthy of Hollywood.

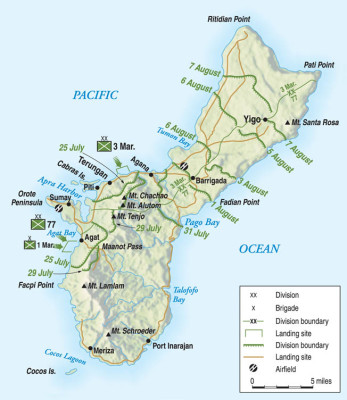

The front lines are the province of the infantry, and others tread in this realm at their peril. Even the infantry, however, fears artillery, over which it has little control. During World War II, the U.S. Army pioneered the development of effective forward observer parties to precisely control the fire of its supporting guns. Big Guns, Brave Men: Mobile Artillery Observers and the Battle for Okinawa (Rodney Earl Walton, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 229 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $36.95, hardcover) tells the story of one battalion’s forward observers during the desperate and bloody battle for Okinawa.

The front lines are the province of the infantry, and others tread in this realm at their peril. Even the infantry, however, fears artillery, over which it has little control. During World War II, the U.S. Army pioneered the development of effective forward observer parties to precisely control the fire of its supporting guns. Big Guns, Brave Men: Mobile Artillery Observers and the Battle for Okinawa (Rodney Earl Walton, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 229 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $36.95, hardcover) tells the story of one battalion’s forward observers during the desperate and bloody battle for Okinawa.

The author, whose father was one of those observers, conducted and gathered numerous interviews with members of the 361st Field Artillery Battalion and the units it supported as part of the 96th Infantry Division. This organization was blooded on Leyte in the Philippines but met its true test on Okinawa in mid-1945.

The use of forward observers is well documented, but this work focuses on these teams specifically. The observer, normally a lieutenant, was supported by a small team of enlisted soldiers. Artillery techniques, heavy on mathematics, are usually only touched upon, but here the author attempts to explain the details of adjusted fire, preplanned concentrations, and the protective fire used at night when American troops went on the defensive and the Japanese attempted counterattacks.

On Okinawa these soldiers were sorely tested as each advance was bitterly challenged. The Japanese occupied a series of defensive lines and were themselves amply supplied with artillery. The U.S. commander, General Simon Bolivar Butler, Jr., who would die during the campaign, knew artillery was an American strength and planned for its heavy use. With such a free hand, the observer teams were kept busy. By the end of the fighting, many gun tubes were worn out, no longer capable of accurate fire.

The dangers of short rounds or friendly fire are also frankly discussed. An observer could become unpopular with the infantry he supported if rounds landed short and caused U.S. casualties. This was true even if the incident was not the observer’s fault. Fatigue, stress, and inexperience all contributed to the problem, which was never fully solved.

Japanese American soldiers struggled on two fronts in World War II. They faced combat against the Germans in Italy and Western Europe during 1944-1945. For the entire war they fought prejudice, segregation, and hostility from their fellow Americans. By war’s end their primary unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was one of the most decorated units in the U.S. Army. Going for Broke: Japanese American Soldiers in the War Against Nazi Germany (James M. McCaffery, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013, 408 pp., photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover) uses the 442nd motto “Go for Broke” to encapsulate the unit’s effort to prove itself to the country it faithfully served.

Japanese American soldiers struggled on two fronts in World War II. They faced combat against the Germans in Italy and Western Europe during 1944-1945. For the entire war they fought prejudice, segregation, and hostility from their fellow Americans. By war’s end their primary unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was one of the most decorated units in the U.S. Army. Going for Broke: Japanese American Soldiers in the War Against Nazi Germany (James M. McCaffery, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013, 408 pp., photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover) uses the 442nd motto “Go for Broke” to encapsulate the unit’s effort to prove itself to the country it faithfully served.

Formed at the beginning of 1943, the regiment’s origins really go back to Pearl Harbor and its aftermath. The fear that swept America concerning citizens of Japanese descent resulted in their essential imprisonment and loss of rights as well as denial of the ability to serve in the military, except for a number of men already in the Hawaiian National Guard. Argument over the morality of these actions raged until the government relented and allowed military enlistment. Once the unit was created, many men flocked to it, eager to demonstrate that not only themselves but also their people were Americans.

Initially the unit went to Italy, where it entered combat near Belvedere. From then on, the 442nd garnered a reputation for bravery and determination. By late September 1944, the regiment was withdrawn from the line and sent to France to reinforce the U.S. Seventh Army as it fought its way into Germany. In late October, a battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment found itself surrounded by German troops, and the 442nd was sent to break through the encirclement. The 442nd succeeded in relieving this “Lost Battalion.”

By the end of the war, this unit’s achievements could be measured by the high casualties it suffered in the accomplishment of its missions and by the decorations its soldiers earned, including Distinguished Service Crosses, Silver and Bronze Stars, and Purple Hearts. Sadly it took until after the war for 21 of those awards to be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Normandy is famous as the landing point for the Western Allies in June 1944. Today it is known for its brandy and cheese. However, there are still remnants of bunkers and cemeteries bearing the graves of those who died during the German occupation. Their story is documented in Normandy in the Time of Darkness: Everyday Life and Death in the French Channel Ports 1940-45 (Douglas Boyd, Ian Allen, Surrey, UK, 2013, 256 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover).

Normandy is famous as the landing point for the Western Allies in June 1944. Today it is known for its brandy and cheese. However, there are still remnants of bunkers and cemeteries bearing the graves of those who died during the German occupation. Their story is documented in Normandy in the Time of Darkness: Everyday Life and Death in the French Channel Ports 1940-45 (Douglas Boyd, Ian Allen, Surrey, UK, 2013, 256 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover).

French citizens had to face two enemies during the war. Every day they had to fear the occupying Germans. Property might be taken by the Wehrmacht with no recourse. Short of labor, the Germans might forcibly take men for construction duty. The SS and Gestapo were ever present threats and could take whomever they wanted at any time. French police had no choice but to assist their overlords in enforcement of German regulations. After the Allied invasion, retribution was often meted out by the retreating Nazis, especially against those thought to be resistance fighters or their supporters.

Their second foe was the Allies themselves. In their prosecution of the war, the Allies had to bomb France in order to harm the common enemy and pave the way for eventual liberation. In doing so, thousands of French were killed in air raids, shore bombardments, and other unfortunate actions during the total war inflicted on the nation by its friends. There was debate over whether the widespread bombing campaign was justifiable considering the number of French expected to be killed. The British were the most reluctant to bomb France in this way, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill thought 20,000 or more might be killed by the bombing campaign, though some British officers though it had to be done to win the war. The American leadership largely thought it was part of the high price of victory and urged going ahead with the dread task. It was done, and a postwar French assessment placed the number of French killed by bombing at 60,000.

The Japanese conquest of Malaya and Singapore was a heavy blow to Great Britain. Unprepared for the onslaught and engaged in a bitter fight against Germany and Italy, Britain could do little but watch as its Far Eastern bastion fell. The situation was bad for Churchill and the government, but infinitely worse for the soldiers taken prisoner by victorious Japan. One such group was the Lanarkshire Yeomanry of the Royal Artillery. Their experience fighting and as prisoners is retold in Death Was Our Bedmate: 155th (Lanarkshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment and the Japanese 1941-45 (Agnes McEwan and Campbell Thomson, Pen and Sword, South Yorkshire, UK, 2013, 212 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, index, $39.95, hardcover).

The Japanese conquest of Malaya and Singapore was a heavy blow to Great Britain. Unprepared for the onslaught and engaged in a bitter fight against Germany and Italy, Britain could do little but watch as its Far Eastern bastion fell. The situation was bad for Churchill and the government, but infinitely worse for the soldiers taken prisoner by victorious Japan. One such group was the Lanarkshire Yeomanry of the Royal Artillery. Their experience fighting and as prisoners is retold in Death Was Our Bedmate: 155th (Lanarkshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment and the Japanese 1941-45 (Agnes McEwan and Campbell Thomson, Pen and Sword, South Yorkshire, UK, 2013, 212 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, index, $39.95, hardcover).

The regiment was a Territorial, or reserve unit, called to duty in September 1939. Initially cavalry, in 1940 they were converted to artillery. By December 1940, they had received orders for “a tropical climate,” and after a stop in India arrived in Malaya in September 1941. With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan’s coordinated strike into Southeast Asia went into full swing, and a day later Japanese troops were landing on Malaya’s shores. Establishing a beachhead, the Japanese Army carried out its own blitzkrieg and within months took Malaya and Singapore. During this time, the regiment acquitted itself well and supported British, Indian, and Gurkha troops. Its fighting retreat ultimately failed, and the 155th was among the units forced to surrender.

Life as prisoners started badly and only got worse. During the beginning, the men were guarded by Indian troops who had switched sides to the Japanese. They treated their former allies harshly, some taking delight in avenging themselves against their supposed former masters. As their captivity stretched on through the war years, the unit was split up as men were parceled out to various work projects. Some were kept in Southeast Asia and forced to work on the infamous Burma Railway. Others were taken to a copper mine on Formosa. Still more were transported to Borneo and even Japan. In all these places, they toiled, suffered, and died, waiting for their eventual liberation in September 1945.

New and Noteworthy

The Stalingrad Cauldron: Inside the Encirclement and Destruction of the 6th Army (Frank Ellis, University of Kansas Press, 2013, 512 pp., $39.95, hardcover). This book looks at the encirclement of Stalingrad from the perspective of the German soldiers trapped inside the city. It includes previously unpublished accounts, newly translated.

The Stalingrad Cauldron: Inside the Encirclement and Destruction of the 6th Army (Frank Ellis, University of Kansas Press, 2013, 512 pp., $39.95, hardcover). This book looks at the encirclement of Stalingrad from the perspective of the German soldiers trapped inside the city. It includes previously unpublished accounts, newly translated.

The Hundred Day Winter War: Finland’s Gallant Stand Against the Soviet Army (Gordon F. Sander, University of Kansas Press, 2013, $39.95, hardcover). A translation of a Finnish bestseller on the bitter defense and eventual defeat of Finland by the Soviet Union.

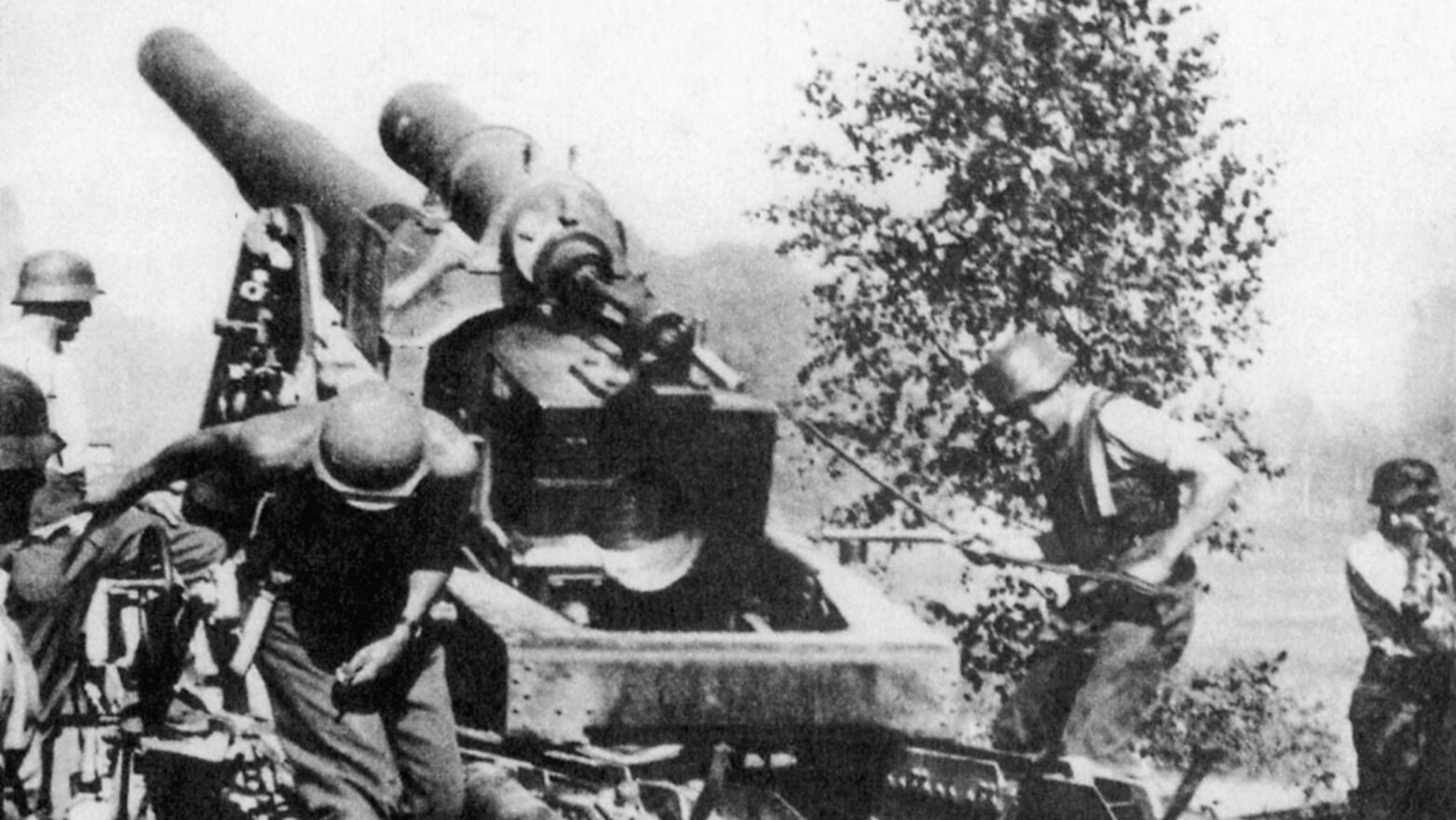

Steel Thunder on the Eastern Front: German and Russian Artillery in WWII (Chris Evans, Stackpole Books, 2013, 208 pp., $24.95, hardcover) This book is a photo essay of the various artillery pieces used by both combatants on the Eastern Front. The bulk of the images are from private collections worldwide.

Tiger (Thomas Anderson, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2013, 256 pp., $29.95, hardcover) This is an overview of the quintessential German tank. Included are development history, variants, service, and where to find remaining examples.

Engineers of Victory: The Problem Solvers Who Turned the Tide in the Second World War (Paul Kennedy, Random House, 2013, 464 pp., $30.00, hardcover) The author asserts that the war was won not only by generals and politicians, but also, engineers, logisticians, and analysts. The organizational and business culture of the Allies allowed middle management to prosecute the war.

Unsung Eagles (Jay Stout, Casemate, 2013, 320 pp., $32.95, hardcover) This is an oral history relating the stories of 22 different pilots and how they experienced—and won—the war. It includes both the Pacific and European Theaters.

Finding the Few (Andy Saunders, Grub Street Publishing, 2013, 192 pp., $24.95, softcover) Many of the pilots who fought the Battle of Britain were lost without a trace. The author and others found a dozen of them through long research and helped bring closure to the families of these fallen airmen.

Finding the Few (Andy Saunders, Grub Street Publishing, 2013, 192 pp., $24.95, softcover) Many of the pilots who fought the Battle of Britain were lost without a trace. The author and others found a dozen of them through long research and helped bring closure to the families of these fallen airmen.

Disarming Hitler’s V Weapons (Chris Ransted, Pen and Sword, 2013 256 pp., $39.95, hardcover) Of the V1 and V2 rockets launched at England, almost half failed to function, and their wreckage lay strewn across Europe and England. This is the story of the teams dispatched to recover the weapons and discover their secrets.

Convoy Will Scatter: The Full Story of Jervis Bay and Convoy HX84 (Bernard Edwards, Pen and Sword, 2013, 224 pp., $39.95, hardcover) Convoy HX84 was eastbound when attacked by the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer in November 1940. Though outgunned, the armed merchant cruiser Jervis Bay engaged but was defeated.

Survivor: Auschwitz, the Death March and My Fight for Freedom (Sam Pivnik, St. Martin’s Press, 2012, $30.00, softcover) This book tells the story of Sam Pivnik, a Holocaust survivor who endured a Polish ghetto, six months in Auschwitz, a mining camp, and then a death march to the east. Put aboard the prison ship Cap Arcona, he was one of only a few to survive its sinking.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments