By Michael D. Hull

When German forces rumbled across the Polish frontier in the early hours of Friday, September 1, 1939, igniting World War II, it was the speed and mobility of the armored divisions—the Panzerwaffe—that stunned the world.

They symbolized the iron-clad menace of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich unleashed upon an indecisive, unready Europe, and represented a fearsome new mode of warfare: blitzkrieg. The panzers seemed to be unstoppable and would be found at almost every decisive moment of the war—in the bocage country of France, the bleak steppes of Russia, and the deserts of North Africa. They achieved their greatest victory in May 1940, when seven panzer divisions churned through the “impassable” Ardennes Forest; rolled across the frontiers of Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg; and raced for the English Channel coast. Despite setbacks inflicted gallantly by 16 British Mark II Matilda infantry tanks at Arras and a French armored division led by General Charles de Gaulle, the panzers ground on, split the Allied armies, and forced the British to evacuate from Dunkirk.

Blitzkrieg in the West proved that ingenuity and audacity can sometimes be as decisive as firepower, say Peter McCarthy and Mike Syron in Panzerkrieg (Carroll & Graf, New York, 2002, 310 pp., photographs, maps, glossary, notes, index, $26.00 hardcover), their authoritative and articulate history of the rise and fall of the German armored forces. Based on scrupulous research and rich in fascinating detail about panzer operations, equipment, technology, and leaders and heroes, this is a vital addition to World War II literature.

Blitzkrieg in the West proved that ingenuity and audacity can sometimes be as decisive as firepower, say Peter McCarthy and Mike Syron in Panzerkrieg (Carroll & Graf, New York, 2002, 310 pp., photographs, maps, glossary, notes, index, $26.00 hardcover), their authoritative and articulate history of the rise and fall of the German armored forces. Based on scrupulous research and rich in fascinating detail about panzer operations, equipment, technology, and leaders and heroes, this is a vital addition to World War II literature.

The authors follow the Panzerwaffe to Russia, where it came within a hair’s breadth of victory outside Moscow in the winter of 1941 and again before the Stalingrad disaster, and south to North Africa, where it was just a few miles from Alexandria when defeated at El Alamein by the superior British Eighth Army. The panzers’ swan songs came at Kursk and the Battle of the Bulge. Although German tankers were still able to seize local victories from the jaws of defeat, as in Michael Wittmann’s almost single-handed mauling of a British tank brigade at Villers-Bocage in June 1944, blitzkrieg was never successful again.

McCarthy and Syron point out that the high-water-mark blitzkrieg of May 1940 created a myth in the fearful West of whole armies of German tanks, yet the Panzertruppen never constituted more than 10 percent of Wehrmacht manpower. The panzers were outnumbered in armor in France and Russia, and increasingly so as the war continued.

Germany built about 30,000 tanks during 1939-1945, while America turned out 49,000 medium Shermans and Russia fielded 70,000 powerful T-34s. The real superiority of the Panzerwaffe, say the authors, lay in the quality of its officers and men. British, American, and Soviet tank crews never attained the same level of skill as the panzer men. Their officers were consummate professionals who understood armored warfare better than their foes—men like Heinz Guderian, Erwin Rommel, Erich von Manstein, Hasso von Manteuffel, Fritz Bayerlein, and Hermann Balck.

On the strategic level, McCarthy and Syron conclude, the Panzerwaffe was squandered by Hitler and his High Command satraps, and many divisions were destroyed because of senseless orders hampering their mobility; however, on the tactical level, the panzer groups remained cohesive and resolute to the end. Without the negative influence of Hitler and the OKW (High Command) on its operations, the Panzerwaffe could well have won the European war or at least imposed a stalemate.

McCarthy is a journalist in County Waterford, Ireland, and Syron is an archeologist in County Mayo, Ireland. Theirs is a crisp, comprehensive, and convincing overview.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Deceptions of World War II by William B. Breuer, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002, 242 pp., photographs, notes, index, $24.95 hardcover.

Pushed back to a remote railway station called El Alamein in northern Egypt, the British Eighth Army built up its strength in the late summer of 1942 for Operation Lightfoot, a decisive offensive aimed at sending the vaunted German Afrika Korps reeling back once and for all.

A preponderance of men and firepower was the only way that then-General Bernard L. Montgomery believed he could defeat his wily opponent, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. But a major problem confronted the British in their buildup: how to conceal 150,000 men, 1,000 artillery pieces, 1,000 tanks, and 6,000 tons of supplies on terrain—flat, hard, scrubby sand with scant cover—that was visible from the enemy positions.

The challenge was handed to Colonel Dudley Clarke, an expert in unorthodox warfare; Major Jasper Maskelyne, a celebrated former magician; and Lt. Col. Geoffrey Barkas, a camouflage expert and former film producer. They undertook a remarkable feat of illusion that fooled the Germans, as William Breuer explains in his history of deceptions in World War II.

Two thousand tons of fuel cans were layered in slit trenches, undetectable from German reconnaissance planes; stores were covered in camouflage nets to resemble ordinary three-ton trucks; field guns, prime movers, and limbers were camouflaged and moved forward stealthily and gradually at night; tanks were covered with large wood-and-canvas “sunshields” to resemble 10-ton trucks; telephone poles in gun pits masqueraded as artillery; a dummy pipeline was laid; and heavy radio communication originated from the southern sector of the front to make the enemy think that the attack would come from there.

Not knowing where Monty would strike, Rommel unwisely split his armored forces to cover both the northern and southern sectors. Then, told by his intelligence officers that the British could not attack for at least a month, the Desert Fox departed to undergo medical treatment in Germany.

Late on the night of October 23, 1942, a thousand field guns thundered to pave the way for squadrons of Cruiser, Matilda, and Sherman tanks and a phalanx of resolute British and Commonwealth infantry, accompanied by sappers and bagpipers. It was the beginning of the end for the Afrika Korps.

The prolific and readable William Breuer has done it again—with a collection of authentic stories about wartime ruses, fakery, and schemes that both enlightens and entertains. His narrative style is bright, and he has an unerring eye for the curious and bizarre.

The tales range from Adolf Hitler’s attempt to “Nazify” 30 million Americans with propaganda to actress Greta Garbo’s undercover work for the British; and from the German intelligence plot to kidnap Pope Pius XII “for security reasons” to beautiful, pigtailed Niuta Teitelbaum, a Polish Jew, who singlehandedly tracked down and executed high-ranking SS officers. Many of these stories will surprise the most committed World War II buffs.

Besides several such books on offbeat aspects of the war, Breuer has written studies of the North African, Sicily, Anzio, Southern France, and Philippine invasions, PT-boats, Nazi espionage in America, and the Rhine crossings.

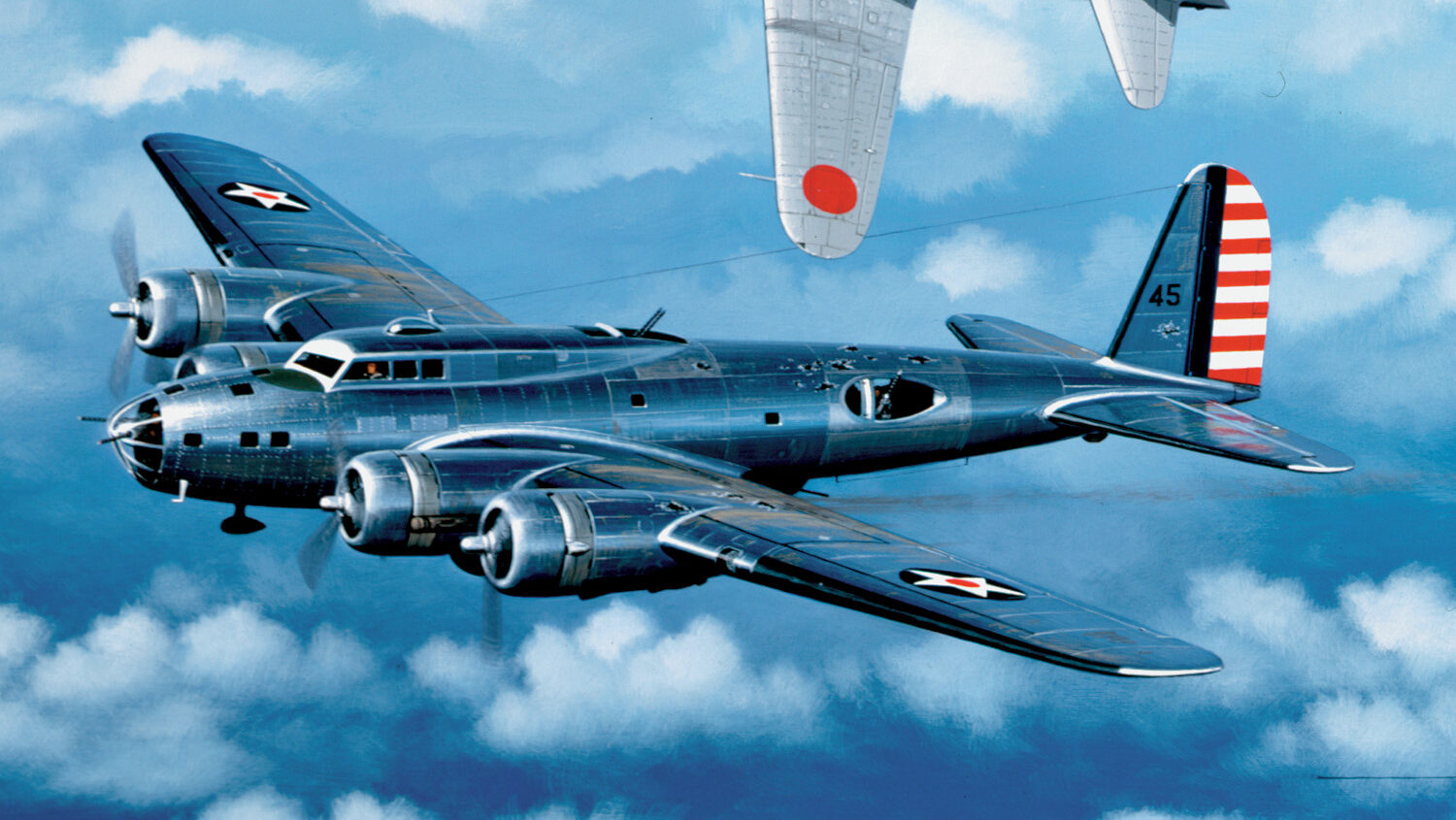

Sunburst by Mark R. Peattie, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 365 pp., photographs, drawings, maps, notes, appendices, index, $36.95 hardcover.

Sunburst by Mark R. Peattie, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 365 pp., photographs, drawings, maps, notes, appendices, index, $36.95 hardcover.

In the early hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, the first wave of aircraft from Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s carrier strike force streaked toward the tranquil, green hills of Oahu.

By 10 am, as the second wave of raiders departed from the skies over Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Pacific Fleet battle line at Ford Island had been shattered, and aircraft parked at Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows airfields and the Kaneohe Naval Air Station lay in smoking shambles.

Three days later and 7,000 miles westward, Japanese naval air power scored a stunning blow at sea by sinking the proud British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse off the coast of Malaya. It was the first time in history that capital ships underway had been sunk in an attack carried out exclusively by airplanes.

Meanwhile, flocks of Japanese medium bombers lifted off from coral airstrips at bases in Micronesia to attack American Pacific outposts, Navy fighters and bombers headed from Taiwan to strike Luzon, carrier planes flew westward to hit Mindanao, and medium bombers took off from air bases near Saigon to lead the Japanese assault on British Malaya. These great aerial deployments were aimed at achieving a vast empire in Asia and the Pacific, which, once occupied by ground forces, would be held against the Western enemy in large part by Japanese naval air power.

In the first six months of the 1941-1945 Pacific War, naval air power spearheaded the offensive operations undertaken by Japan, as Mark Peattie shows in his rigorously researched and wide-ranging analysis of the rise of Japanese naval air power from 1909 to 1941. The former educator, U.S. Information Service staffer, and research fellow traces in exhaustive detail both the development of the Imperial Combined Fleet’s land-based air power and the evolution of its carrier forces, examines its strengths and weaknesses, provides the most complete account available in English of the naval air campaign over China in 1937-1941, and describes the utter destruction of Japanese naval air power by 1944.

While it existed, says the author, the First Air Fleet gave new directions to naval warfare and was the most powerful formation afloat. But, in the onrush of Japanese naval expansion and the assumption that Nippon would fight a short and victorious war, little attention was paid to the critical problem of logistics. There was a paucity of spare parts, an inadequate combat-theater maintenance system and, worse, only enough aviation fuel and lubricants for a year and a half of operations.

This was to clamp a fatal throttle-hold on Japanese naval air power. Meanwhile, Peattie points out, the disbandment of the First Air Fleet after the Battle of Midway on June 4-6, 1942, was a major tactical mistake.

Scholarly, articulate, and eminently informed, this is the first comprehensive account in English of the only force that came close to defeating the U.S. Navy.

The Solomons Campaigns 1942-1943 by William L. McGee, BMC Publications, Santa Barbara, Calif., 2002, 639 pp., photographs, maps, notes, appendices, index, $39.95 softcover.

The Solomons Campaigns 1942-1943 by William L. McGee, BMC Publications, Santa Barbara, Calif., 2002, 639 pp., photographs, maps, notes, appendices, index, $39.95 softcover.

When U.S. Navy SBD Dauntless dive-bombers destroyed four Japanese aircraft carriers at Midway in June 1942, it was a major victory that halted Japan’s southward expansion in the Pacific Ocean.

It was the most decisive naval victory since the Battle of Trafalgar, and a turning point of World War II. However, says Navy veteran and historian William McGee, code-breaking skills and luck were on the American side. Midway was a three-day carrier air fight that turned in a matter of minutes.

By contrast, he says, the Guadalcanal campaign in the Solomon Islands, 1942-1943, the first amphibious operation undertaken by the United States since 1898, took 26 weeks of hard fighting by Navy, Marine Corps, and Army units to secure what had been occupied in little more than a day.

Thus, as McGee writes in the second volume of his series, Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII, he considers Japan’s defeat in the bloody struggle for Guadalcanal to be the key turning point of the Pacific War. Through night operations at sea, the enemy was able to land reinforcements and supplies on the big island.

The result, says McGee, was almost continuous ground fighting by U.S. Marines and Army troops against tenacious defenders. During the course of the battles for the Tenaru and Matanikau Rivers, Bloody Ridge, Henderson Field, Point Cruz, Gifu, and Galloping Horse, U.S. warships fought seven major engagements in the Solomons, more bitter and costly than any naval actions in American history since 1814.

Covering the Guadalcanal campaign from August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943, this is a broad-ranging and informative study, a masterwork of extensive research, brisk prose, and convincing analysis. Besides being a wonderfully comprehensive overview of operations in the Solomons, from Tulagi and Savo Island to Tassafaronga and Rennell Island, McGee’s volume provides considerable detail about the American and Japanese sea, ground, and air units involved; planning and logistics; leaders and heroes; equipment and weaponry; the costs and the lessons learned.

In this campaign, says the author, American ground planners learned that they would have to improve their ability to estimate enemy strength and defenses, and to better organize logistical support, while the Navy would have to develop more effective nighttime tactics. McGee has high praise for the Marines, soldiers, sailors, and airmen who served in the Solomons, with a special tribute for such unsung stalwarts as the Navy Seabees, the Army and Navy engineers, and those who toiled in base depots.

Part I of this book is a condensation of Volumes IV and V of Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of United States Naval Operations in World War II.

Montana-born McGee enlisted in the Navy in 1942, served at Guadalcanal himself and in the 1946 Bikini Atoll atomic-bomb tests, and was later a broadcaster.

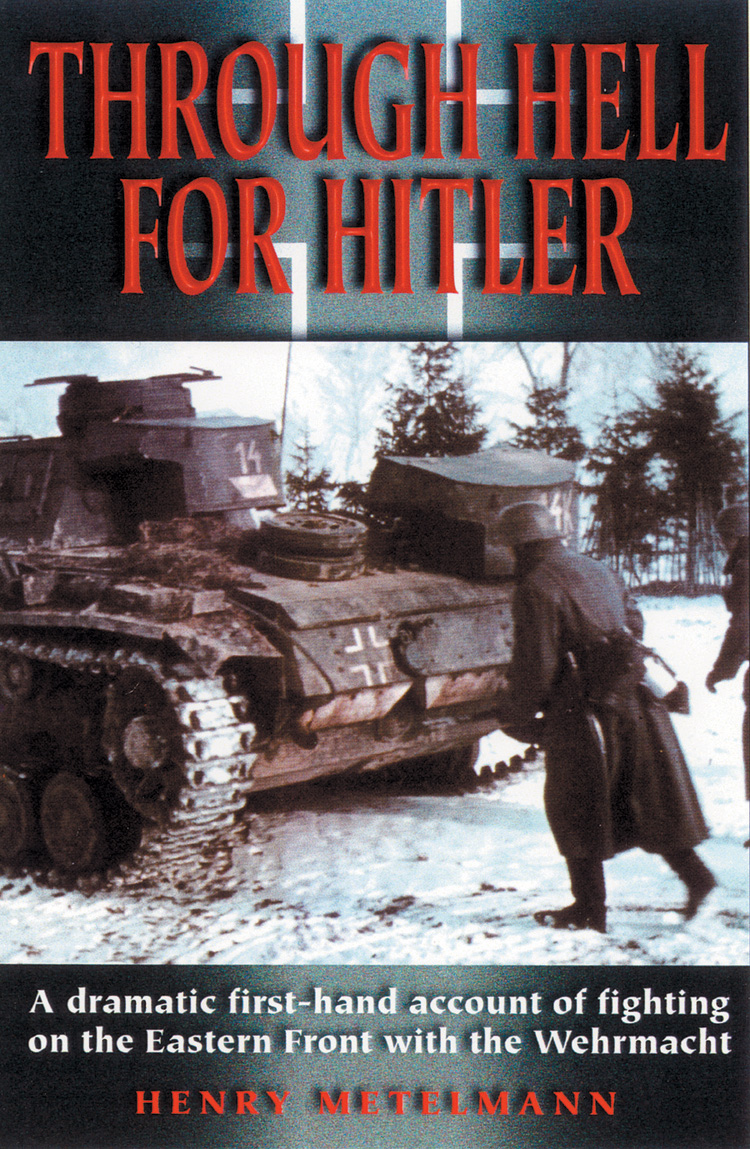

Through Hell for Hitler by Henry Metelmann, Casemate Books, Havertown, Pa., 2002, 208 pp., photographs, index, $29.95 hardcover.

Through Hell for Hitler by Henry Metelmann, Casemate Books, Havertown, Pa., 2002, 208 pp., photographs, index, $29.95 hardcover.

After the destruction of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad in January-February 1943, panzerjager (tank driver) Henry Metelmann, 20, of the 22nd Panzer Division was pressed into service as a grenadier in a 200-man kampfgruppe (battle group).

“Most of us were in our early 20s, and though we were sullen, suspicious, and frustrated, we were not mentally beaten; not yet,” he said. “Though all the idealism pumped into us about what we were fighting for here in Russia had completely evaporated, and we had no hope left for victory, we were still determined to get back to Germany in one piece. And we knew that our only chance for that was in fighting together.

“We knew now how the Russians must have felt during the early part of [Operation] Barbarossa, when all they could effectively do was run away from our pincer movements. The boot was now on the other foot. And the Russians were now proving to be extremely capable and courageous soldiers, giving the lie to our earlier preconceptions, based on our supposed racial superiority.”

Born into a poor family in Altona, near Hamburg, on Christmas Day 1922, the slender, pensive Metelmann was a committed National Socialist and a member of the Hitler Youth before being called up to the German Army in 1940. He joined a panzer division in 1941 and served in France before being sent to the Eastern Front.

In the first stages of the campaign, the Germans swept all before them as they advanced across the endless steppes, Metelmann writes in his plain-spoken, vivid, and powerful memoir. But, as the Wehrmacht struck deeper into the Russian heartland and as the Red Army and the harsh Russian winter started to take an increasing toll on the invaders, Metelmann grew disillusioned and began to question the justness of this savage conflict.

After he and his comrades were billeted with Russian peasants during the harsh winter, the young driver of PAK artillery half-tracks and captured T-34 tanks realized that the people were not subhumans after all. There is much humanity and pathos in his narrative to counter the brutality and suffering endured by both sides. His unit went by way of southern Russia to the crucible of Stalingrad, and then into the massive Battle of Kursk in July 1943. Eventually, as Metelmann, the determined survivor rather than the hero, records, victory turned into total defeat in the white hell of Russia, and the remnants of the once-confident Wehrmacht fled in an epic retreat.

Metelmann surrendered in 1945 and was shipped to POW camps in Arizona and then England. After spending a short, unsatisfying time in his homeland, he returned to live in southern England, worked as a gardener and railway signalman, and married a Swiss girl. He now lives in Surrey.

During his soldiering, and against regulations, Metelmann jotted down his observations in small notebooks. Many years later, settled amid the mellow villages and tranquil meadows of Hampshire, he was persuaded to write a personal account of the most terrible front in World War II, as both a tribute to the fallen and a warning for today. “When will we ever learn?” he asks. Perceptive, revelatory, and poignant, this is a unique chronicle of the 1941-1945 Russo-German war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments