by Eric Niderost

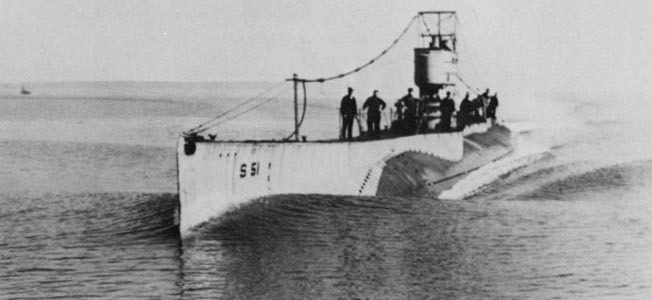

Early Navy submarines, notably the S-class models, were so dangerous and cramped they were derisively labeled “pig boats.”

[text_ad]

Deplorable Conditions Onboard Early Subs

The S-class boats were small, limited in range, and could only submerge for comparatively short periods. Conditions aboard the S-boats were horrible, in fact almost beyond belief. There were no refrigeration, no air conditioning, and no toilets. A bucket half-filled with oil served as a latrine, and the air was heavy with the acrid stench of unwashed bodies, human waste, oil, and sometimes spoiled food.

By contrast, the Sargo-class Sculpin and Squalus were a whole new breed of submarine, designed for long-range independent missions. The first thing that old submariners noticed was their size. There were 310 feet long, 27 feet wide, and displaced 1,450 tons, making them almost twice as large as their S-class predecessors. Earlier submarines had been so small navy men took to calling them “boats.” The name stuck to all submarines, even large fleet vessels like Sculpin and Squalus, and to this day submarines are called “boats.”

Underwater “Coffins For Heroes”

Older submarines had been dangerous, and all too frequently vessels were lost with all hands. In 1927, for example, the S-4 sank off Cape Cod at a depth of 100 feet. Many crewmen were alive, tapping out messages in hopes of salvation, but rescue efforts were hampered by bad weather and the fact that there was no way to reach them. All perished, causing a public outcry against these underwater “coffins for heroes.”

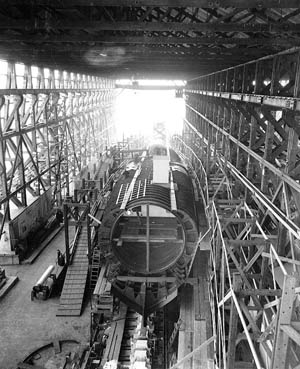

The Navy responded to the criticism, and new boats like Sculpin and Squalus featured improvements like backup onboard systems, hull-stop valves in every compartment to plug leaks, and watertight bulkheads between compartments. Lieutenant Commander Charles “Swede” Momsen dedicated his life to improving the safety of America’s submarines. Thanks to his innovative genius and complete dedication to the task at hand, Momsen breathing lungs became standard on all fleet submarines.

New Class Of Subs Designed For Enhanced Safety and Comfort

Submarines like Sculpin and Squalus also featured specially designed escape hatches, portals that could bond with the experimental diving bell Momsen was developing. If Squalus’s escape hatches had not be compatible with the McCann Rescue Chamber the story of her crew’s rescue would have ended quite differently.

Modern fleet submarines boasted such amenities as cold and deep-freeze storage for perishable food. There were also air conditioning, a blessing when cruising in tropical waters, and flush toilets. Old salts had a veteran’s disdain for such luxuries, calling them “hotel accommodations,” but newer submariners appreciated them. Anyone visiting a WWII fleet submarine today, several exist as museums, is stuck by the claustrophobic arrangement of pipes, knobs, and equipment. But compared to the old S boats, fleet submarines were roomy in the extreme.

The primary focus of a fleet submarine was war, not creature comforts, and new boats like the Sculpin and Squalus packed a lethal punch. There were four forward torpedo tubes and four stern tubes, each capable of lunching deadly 21-foot-long “fish.”

Formidable Fighting Vessels

A 3-inch gun and .50-cal. machine gun were on deck, the former more to finish off torpedoed targets than to shoot it out with surface craft.

Above all, Sargo-class vessels, and all subsequent boats in World War II, were designed to easily cruise the vast open stretches of the South Pacific. Sargo-class submarines like Sculpin and Squalus had a patrol endurance of 75 days and a cruising range of 11,000 miles at 10 knots.

But what were such boats supposed to do with all that range and power? Submarines like Sculpin and Squalus were modern in design, but the theories that gave them birth proved anachronistic. Their very name “fleet submarine” reveals much about naval theory as it existed in the 1930s. Many of the navy’s top brass were mesmerized by the great capital ships that still dominated most of the world’s fleets. Battleships were supposed to slug it out with their opposite numbers until superior firepower and tactics won the day.

A Changing View Of Naval Wafare

The idea of a great and decisive sea battle was a heady thought, sanctified by long tradition. But such thinking relegated submarines to scouting chores, racing ahead to reconnoiter and inform the surface fleet of the enemy’s whereabouts. The theory allowed that subs might “soften up” the enemy by torpedoing a ship or two, but major offensive action was deemed out of the question. Anything that a submarine would do would be a “warm up” to the main event, namely a great sea battle waged by capital ships.

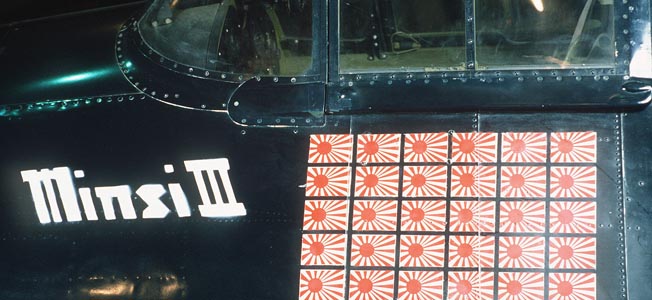

Of course, such thinking was proved an anachronism when war finally broke out. U.S. submarines were hampered by faulty torpedoes during the first two years of the war, though they still chalked up some impressive scores. The U.S. fleet submarine really came into its own during the last two years of the war. The Silent Service comprised less than two percent of the United States Navy, yet it was responsible for 55 percent of all Japanese shipping tonnage sunk, including one-third of their warships. It was an outstanding record and ample testimony to the effectiveness of the submarine as an offensive weapon of war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments