By Martin K.A. Morgan

As the sun rose higher and higher, Major Raymond H. Wilkins sat in the cockpit of his B-25 bomber waiting for the go order. For the third day in a row, he and the other aircrews from the 8th Bombardment Squadron rose at 0400 hours, ate breakfast, and then manned their planes at 0630 hours. The two previous days ended with the mission being canceled due to bad weather over the target area. The news was met with a combination of relief and frustration because this target was an intimidating and dangerous one—the Japanese fleet anchorage at Simpson Harbor, Rabaul, on the island of New Britain. A combat mission was nothing new for Major Wilkins—he had been flying them against the Japanese for almost two years in the Southwest Pacific Theater. Although this was to be his 87th mission, a strike against Rabaul was nevertheless nothing to be taken lightly. The Japanese desperately needed Simpson Harbor as their primary anchorage supplying the ongoing, vicious battle in the Solomon Islands to the south. Because of this, they would defend it tenaciously from any and all air raids. This would not be a surprise raid either because U.S. Army bombers had been striking Rabaul whenever the weather permitted during the last two weeks. To meet the new threat, the enemy was constantly bringing in more and more personnel, fighter aircraft, and antiaircraft weapons. It was a continuum of escalation that made each successive mission more dangerous than the one before it.

Today’s mission against Rabaul was in many ways the most important raid yet because it was to be the biggest—with 84 B-25s from nine squadrons descending on the harbor in three waves. In addition to that, 84 P-38 Lightning fighters would fly in escort to defend the B-25s. As commander of the 8th Bomber Squadron, Major Wilkins was the leader of just 11 of those 84 B-25s. It was a small percentage of the total bomber strength of the raid, but it was nevertheless a crucial part of the mission because the 8th would go in last. When the time came to organize the three waves during the planning of the raid, Wilkins volunteered his squadron to fly the extremely hazardous tail-end element. He had confidence in his men, confidence in his own experience, and he knew that the 8th Bomber Squadron could be depended on to get in and hit the Japanese ships that would be waiting there. He knew that he was placing the 11 aircraft and 55 men in his command in the position of greatest danger, but somebody had to do it. Wilkins also knew that the B-25 flying the far left flank of his squadron formation would be the aircraft closest to the enemy and therefore the aircraft that would be confronted with the greatest volume of enemy antiaircraft fire. Rather than assign one of the other aircrews to that slot, he took the position himself.

The temperature in the cockpit of Wilkins’s B-25—named Fifi—was getting hotter with every passing minute as the sun began to scorch the US Army airfield at Dobodura near Buna, New Guinea. When the signal to start engines finally came, the sweating air crewmen were relieved to know that they would at least be able to get up to altitude where the temperature was cooler. As Fifi taxied out to take off, the other 10 B-25s of the 8th Bomber Squadron followed. This was it. They were finally going to Rabaul. Whatever thoughts Raymond Wilkins may have had in his mind as he took off were pushed aside to focus on the mission. A little over a month before he had turned 26 years old and he had recently learned that he was being transferred out of the 8th Bomber Squadron and up to 3rd Bombardment Group headquarters. This was in all likelihood the last combat mission he would ever fly. But the big news was that he would be marrying his beautiful Australian fiancée Phyllis (nicknamed Fifi) in just four short weeks. But none of that mattered right now. All that mattered was getting the B-25s to the target to sink as many Japanese ships as they could and then return with all 11 aircraft and all 55 men aboard safe and sound. This was no easy task, though, because by 1943, the B-25 did not fly typical bombing missions.

Originally designed to drop 3,000 pounds of bombs from medium altitudes in level flight, the B-25’s actual role was seldom that during the war in the Pacific. American pilots and air crewmen most frequently found themselves attacking Japanese ships at sea. Dropping bombs on a maneuvering vessel from altitudes of 10,000 feet or more using the Norden bombsight rarely resulted in damaged or sunken ships. Also, higher altitudes meant greater vulnerability to the enemy’s defensive antiaircraft artillery fire and fighter interceptor aircraft. Since that was the case, B-25 air crewmen soon learned that the best way to sink the enemy was to come thundering in at masthead height at 250 mph and release a bomb that would skip across the water once or twice before slamming into the side of the target ship. It was an extremely effective improvised tactic but it meant that the B-25s had to fly through a gauntlet of fire from the decks of the ships they attacked. Because they had to press their attacks so close, it led to field modifications that mounted more and more .50-caliber machine guns on the B-25s flying the antiship skip-bombing missions. With a formidable weapons package on board, B-25s would unleash a withering stream of .50-caliber bullets as they approached Japanese ships. Deck crewmen on those ships would then be forced to dive for cover—preventing them from manning their guns or returning fire at the American bombers attacking them. Thus, the B-25 in the Pacific had evolved from a conventional level-bomber to a strafing gunship that was easily capable of crippling enemy vessels. Major Wilkins’s Fifi was a B-25C that was produced at the North American Aviation company plant in Inglewood, California, during 1942. Like all of the other C-model B-25s serving in the 3rd Bombardment Group, Fifi had been up-gunned before she began to fly skip-bombing missions. The work was done at Eagle Farm airfield near Brisbane on Australia’s east coast and featured the installation of four ANM2 .50-caliber machine guns mounted in the aircraft’s nose and external pods on both sides of the fuselage, each with a pair of additional ANM2s. This meant that Fifi could strafe with the devastating firepower of eight forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns—all of which could be triggered from the cockpit.

About 30 minutes after takeoff—still at the beginning of their 450-mile flight—three of the B-25s turned back to base with fuel transfer problems. Now down to eight aircraft, Major Wilkins continued to lead the squadron east across the Solomon Sea. He knew that the raid needed every last B-25 to succeed and he knew the stakes were high. It was Tuesday, November 2, 1943 and Wilkins was aware that the 3rd Marine Division had landed at Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville, the day before. He knew that the Marines were struggling to hold a beachhead a mere 250 miles from Simpson Harbor and that the Japanese would be launching bombing missions that day from the airfields around Rabaul. What he did not know was that the Japanese had rushed in additional fighters the night before to defend the anchorage—Rabaul was going to be an even tougher target than expected.

As the B-25s droned on at an altitude of 3,000 feet, Wilkins fish-tailed Fifi briefly, signaling everyone to test their guns. The squadron obediently spread out, checked their weapons, and then reassembled into the formation they would use for the attack. Although the guns that gave them such potent strafing firepower were important, the real ship-killing punch that made these B-25s so dangerous was tucked-away inside their bomb bays. Each carried a pair of 1,000-pound high-explosive bombs fused for skip bombing. When the southern tip of the island of New Ireland came into view off Fifi’s left side, Wilkins turned to the north to approach Rabaul from the south by following the length of St. George’s Channel. Soon smoke could be seen on the horizon—the P-38s were already sweeping the target area.

Wilkins continued to approach the harbor by placing Cape Gazelle just off Fifi’s left side. The peninsula forming the cape was dominated by a trio of dormant volcanic cones, behind which lay Simpson Harbor. As the formation passed the southernmost of the volcanoes, Wilkins noted that the squadron immediately ahead failed to turn to the west to fly through the pass between the middle and northernmost volcanoes. That crucial turn would have brought them in right over Rabaul and would have minimized the formation’s exposure to enemy flak. If Wilkins led the 8th Squadron through the pass as the plan called for, it would place them out of sequence and jeopardize the success of the mission, so he chose to follow and preserve the correct order. Thus Fifi and the other seven B-25s flew on as they were led in a circle around the northernmost volcanic peak in a descending 180° turn. This slight navigational error brought the 8th Bomber Squadron in on a flight path that paralleled the waterfront of Simpson Harbor, which significantly lengthened the formation’s exposure to enemy fire. This already dangerous mission had just gotten even more dangerous.

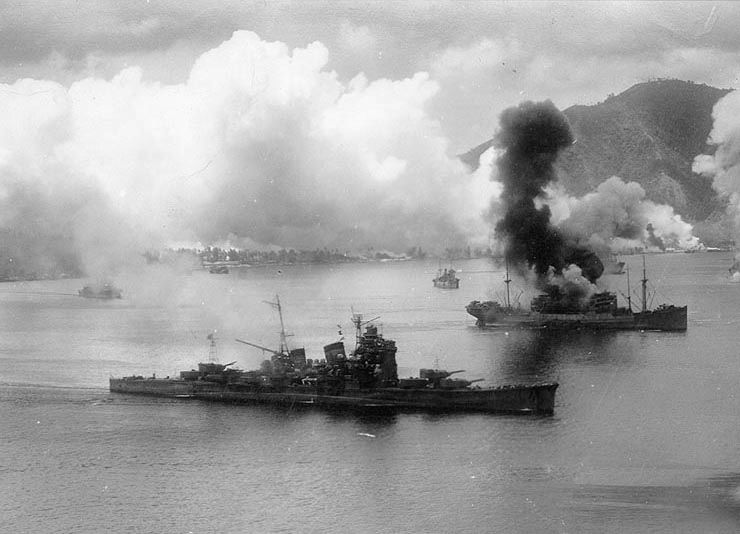

As the squadron thundered in over the port at low altitude, it was immediately obvious that the preceding waves of bombers and fighters had stirred up the hornet’s nest. The air was alive with flak and Fifi—on the far left flank of the formation—drew most of it. Within moments her right wing had been hit and Wilkins began to experience difficulty holding the aircraft in formation. Although the damage was justification enough for him to pull out and let another B-25 take over, Wilkins nevertheless continued to lead the squadron down into Simpson Harbor. When a group of small vessels came into range, Fifi opened fire. With smoke from her .50-caliber machine guns filling the cockpit, the crew noticed a Japanese destroyer attempting to get underway. Fifi’s bomb bay doors opened and her first 1,000-pound bomb fell from its shackles, skipped once on the surface of the water, and then slammed into the side of the destroyer with a devastating explosion. But as Wilkins pulled away from the burning ship, anti-aircraft fire raked Fifi a second time, heavily damaging her left vertical stabilizer. Again, he chose not to abort the mission and pressed on, still leading the squadron. Barely capable of controlled flight, he maneuvered Fifi to attack a 9,000-ton armed transport ship. From below masthead height, the .50-caliber machine guns opened up followed by a second 1,000-pound bomb, which struck the ship and engulfed it in flames.

His aircraft heavily damaged and out of bombs, Wilkins could have justifiably disengaged and headed for home right then but he noticed something menacing in the harbor dead ahead—the 13,000-ton Myÿkÿ-class heavy cruiser Haguro. Recognizing that this heavy cruiser’s guns could pose the greatest threat to his squadron’s B-25s, Wilkins commenced a strafing run against it. Trailing smoke from the damaged right wing, Fifi’s guns began blazing one final time as she raked Haguro with .50-caliber bullets. But the volume of fire the Japanese put up into the air at their antagonist was too great and Fifi’s already wounded vertical stabilizer was quickly shot away. Because of the missing control surface, Fifi began to roll up and to the right toward the next B-25 in the formation. Wilkins avoided the collision by throwing the control column over to the left, which unfortunately exposed Fifi’s belly and wings to the Haguro’s gunners. Then her left wing crumpled and she crashed into Simpson Harbor at full power. There were no survivors.

Despite the fact that the Japanese put up the fiercest opposition the Fifth Air Force would encounter during the entire war, the Rabaul raid of Tuesday, November 2, 1943, was a great success. In less than 15 minutes, the B-25s attacked 41 Japanese ships, leaving behind 114,000 tons destroyed and 300,000 damaged. This success came at a high cost, though: nine P-38 fighters and eight B-25s failed to return to their bases. Forty-five American pilots and aircrew lost their lives in what the Fifth Air Force began to refer to as “Black Tuesday.” Although there were several notable cases of bravery during the raid, the astonishing example of leadership and sacrifice exhibited by Major Raymond Wilkins stood out among them. In March 1944, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

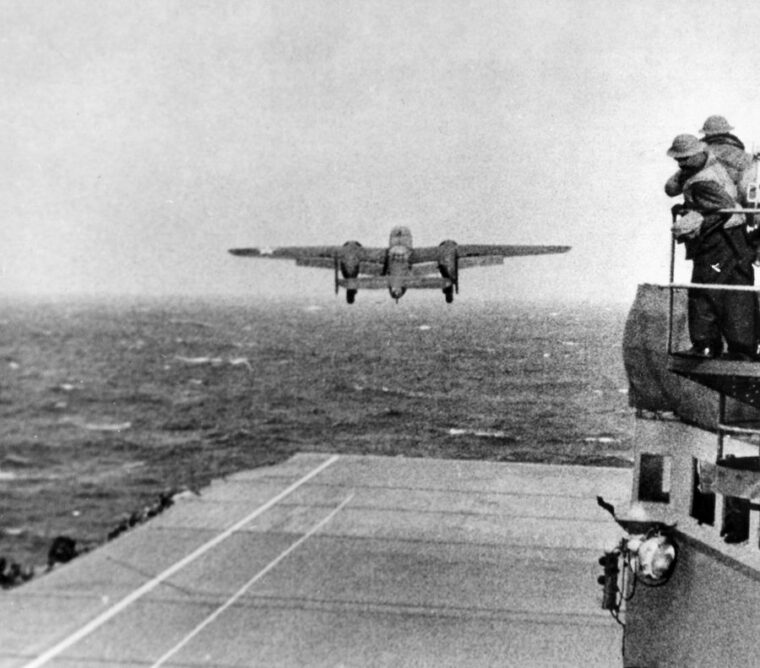

His was not the only Medal of Honor awarded to an American flying the B-25 during World War II. In 1942, Colonel James H. Doolittle received the award for leading a group of 16 B-model B-25s on a raid against several cities on the Japanese home island of Honshu. The daring and ambitious mission involved launching the B-25s from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) and then flying them to a series of airfields in Chekiang Province, China. Although it ran into serious complications and all but one of the B-25s were lost, the Doolittle Raid nevertheless demonstrated that the U.S. military was capable of striking targets in Japan. It also demonstrated the remarkable versatility of the North American B-25 medium bomber.

Through field modifications, evolving tactics, and even aircraft carrier launches and landings, the B-25 proved time and time again that it was among the greatest aircraft of World War II. Designed and prototyped during the years immediately preceding Pearl Harbor, the B-25 concept was to provide the U.S. military with an effective medium bomber and attack platform that could also be sold to European allies. The earliest models had a wing design with a constant-dihedral upward angle from the fuselage to the wingtip. When it was discovered that the airframe had slightly unstable flight characteristics, the problem was solved once and for all by deleting the dihedral on the wings outboard of the engine nacelles—giving the B-25 the distinctive gull-winged appearance that it would keep through the end of production. With a pair of Wright R-2600 Cyclone radial engines, the B-25 was a fast, powerful, and maneuverable bombing platform. As design elements of the aircraft were perfected in the early models, total production numbers remained low: only 40 B-25As and 120 B-25Bs rolled off the assembly line. With the introduction of the B-25C in January 1942, North American had a variant good enough to put into mass production at its Inglewood, California, plant. The new C-model was upgraded to R-2600-13 radials and equipped with a de-icing/anti-icing system for extreme cold weather operations. However, that system was rarely used by the squadrons that flew the C-model B-25s in the Southwest Pacific. The B-25D was identical to the B-25C in every way except that it was produced at the North American Aviation plant in Kansas City, Kansas. Before production ended in 1945, the Inglewood plant produced 1,625 C-models and the Kansas City plant produced 2,290 D-models. When word of the field modified/up-gunned C and D models reached the United States, the Inglewood plant introduced a B-25 specifically designed for tactical close air support, skip-bombing, and strafing missions: the B-25G.

The B-25G was essentially like the earlier C and D models, but differed in that the G had a shortened and enclosed nose mounting a pair of ANM2 .50-caliber machine guns with 400 rounds of ammunition each. The lower left side of the nose enclosure also contained the G-model’s most potent ground attack weapon—a 75mm field gun. This package enabled the pilot to begin a strafing run and, as the .50-cailber bullets from his nose guns walked onto the target, he could then fire a high explosive shell from the 75mm gun. After producing just over 400 B-25Gs, the Inglewood plant introduced an improved and more heavily armed version—the B-25H. The most noticeable new features were a tail gunner’s position, two waist gunner positions, and two additional machine guns in the nose. This gave the H-model a total of 14 ANM2 .50-caliber machine guns and a 75mm canon. It was fast, maneuverable, small, and it packed a mighty punch.

Shortly after the “Bloody Tuesday” raid on Rabaul, the North American Kansas City plant stopped producing the D-model and began producing the most powerful variant of all—the B-25J. This model returned to the glass nose for a bombardier and Norden bombsight, and it retained the tail and waist gunner positions of the H model. The J-model represented the main production variant of the B-25 with a total of 4,390 airframes rolling off the assembly line. Within that production block, North American delivered 800 B-25Js with a solid nose housing an intimidating eight ANM2 .50-caliber machine guns. With the additional side-mounted pods, the dorsal turret, and the tail and waist gunner positions, the B-25J gunship was the most lethal twin engine medium bomber of World War II. When production of the J-model concluded in 1945, just under 10,000 B-25s had been delivered.

Although the U.S. Army was the most prolific user of the aircraft, the U.S. Navy acquired 706 B-25s that were designated PBJ and served in 16 U.S. Marine Corps squadrons. The Royal Air Force and the Soviet Air Force also used the B-25, which fought in every theater of the war. Around the world, by friend and foe alike, the B-25 was known simply as the Mitchell in honor of the late General Billy Mitchell. His passionate and outspoken advocacy of air power elevated him to legendary status. Considering the significant role the B-25 played during World War II, and considering how it evolved as a result of the innovative thinking of American pilots and aircrewmen, there could not be a more fitting namesake.

Yikes! I’d hate to be on the receiving end of that much firepower.