By Michael D. Hull

It was a sunny spring day atop Pine Mountain in Warm Springs, Ga. In his little white pine cottage, where he was resting from the strenuous Big Three conference at Yalta in the Crimea on February 4-11, 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat at a card table in front of the stone fireplace and signed some bills. As was his custom, the genial Roosevelt smiled broadly and joked to his secretary and friend, William D. Hassett, “Here’s where I make a law.”

Shortly before 1 pm that Thursday, April 12, 1945, Hassett left the room. As Roosevelt sat reading a number of documents, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, a Russian-American society artist, sketched him for a portrait. The president had donned a double-breasted gray suit and his Harvard crimson tie. Soft rays from the bright sun slanted through the glass paneled wall of the room. Seated on a sofa were Roosevelt’s cousins, Margaret Suckley and Laura Delano, who had accompanied him to Warm Springs two weeks before. Indicating the papers spread around the room, FDR laughed, “My laundry.”

During his stay at the health resort in Meriwether County in western Georgia, the president had enjoyed ideal weather. He had taken long drives in the broad pine clothed valley around the “Little White House” to which he had first come 20 years before to be treated for infantile paralysis (polio). After having looked haggard and exhausted at Yalta, where his appearance shocked his friend and wartime associate, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Roosevelt was now tanned, appeared to be in good health, and was in fine spirits.

On that afternoon of April 12, Roosevelt planned to go to an old-time Georgia barbecue at the nearby cottage of Warm Springs Mayor Fred Allcorn, and in the evening he was to attend a minstrel show staged by the patients of the Warm Springs Foundation. The following day, Roosevelt was to make a brief radio address to traditional Jefferson Day diners. He planned to return to the White House in Washington on April 20, visit his beloved Hyde Park, N.Y., estate and then head for San Francisco to greet the opening of the United Nations Conference on April 25.

Meanwhile, in the Warm Springs cottage, a mess boy started setting a table for lunch, and FDR said to Shoumatoff, “Now, we have just about 15 minutes more to work.” Then he fainted and slumped in his chair. Two valets carried the President into his unpretentious bedroom and laid him on his plain maple bed. One of his doctors, Navy Commander Howard Bruenn, hurried in. He had FDR’s clothing changed to pajamas, and put him to bed.

Bruenn telephoned Vice Admiral Ross T. McIntire, Roosevelt’s personal physician in Washington, who in turn called Dr. James Paullin of Atlanta and asked him to hasten to Warm Springs. Half an hour later, Bruenn informed McIntire that the president’s condition was “a very serious thing” and that he was certain his patient had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. At 3:35 pm, Roosevelt said, “I have a terrific headache,” he then died. He was 63 years old. He was elegant, cheerful, and brave to the end.

The three correspondents of the United Press, The Associated Press, and the International News Service who had been accompanying the President were waiting for him at the barbecue when they were summoned suddenly at mid-afternoon by Hassett. He told them, “It is my sad duty to announce that the President died at 3:35 pm of cerebral hemorrhage.” The three newsmen dashed for telephones, and bulletins soon flashed the stunning news on teletypes across the nation.

For 12 years and 40 days, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had been the nation’s leader in peace and war. Radiating imperishable self-confidence, energy, and idealism though anchored by steel leg braces, the architect of the New Deal had pulled his people out of the Great Depression, inspired them after the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, and led them to victory in World War II.

The handsome, dashing scion of Dutchess County, New York, wealth and privilege, who had served as assistant secretary of the Navy, governor of N.Y., and been inaugurated as the 32nd President at the age of 51, aroused both a loyalty and opposition unprecedented in American history. He had become almost a family member to all Americans; he was their national father figure and champion. They knew his broad smile, the determined uplift of his square jaw, the cigarette holder jauntily clenched, and his voice. They huddled around their radio sets to listen to his periodic “fireside chats” in which he explained his programs and purposes with measured, elegant simplicity.

The news of his death stilled the nation—a blow to every solar plexus. In bustling New York City, a taxi driver got out of his cab, sat on the curb, and wept. In Pittsburgh, a storekeeper closed up and hung a sign in the window that read, “He died.” In Detroit, a woman said in disbelief, “It doesn’t seem possible. It seems to me that he will be back on the radio tomorrow, reassuring us that it was just a mistake.” In Washington, a young soldier spoke for all when he said, “I felt as if I knew him. I felt as if he knew me—and I felt as if he liked me.”

Yank, the Army weekly magazine, wrote on May 11, 1945, “Under President Roosevelt’s leadership, we have struggled through 12 years of troubled peace and war, 12 of the toughest and most important years in our country’s history. It got so that all over the world, his name meant everything that America stood for. It meant hope in London and Moscow, and in occupied Paris and Athens….We made cracks about it and told Roosevelt jokes, and sometimes we bitterly criticized his way of doing things. But he was still Roosevelt, the man we had grown up under and the man whom we had entrusted with the staggering responsibility of running our war…. And the loss of Roosevelt hit us the same way as the loss of a good company commander. It left us a little panic-stricken, a little afraid of the future…. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death brings grief, but should not bring despair. He leaves us great hope.”

The news of FDR’s death resounded on front pages and from radios across the world. Many nations paid tribute in one form or another. In Moscow, the Soviet government met and stood in silence, and even the Japanese premier expressed “profound sympathy” to the American people.

The chief executive’s wife and fifth cousin, Anna Eleanor, an energetic social reformer and beloved national figure in her own right, was in Washington on April 12, conducting her regular press conference and delivering a brief speech at the Sulgrave Club. Laura Delano telephoned from Warm Springs to say that the President had fainted and been carried to his bed. Later, White House Press Secretary Steve Early called and asked the first lady to come home at once. In her car, Eleanor sat with clenched hands all the way to the White House. “In my heart of hearts,” she said later, “I knew what had happened, but one does not actually formulate these terrible thoughts until they are spoken.”

In her sitting room, McIntire told her that FDR had died. Eleanor was silent for a moment, and then said, “I am more sorry for the people of this country than I am for us.” Vice President Harry S Truman was having a glass of bourbon with some Democratic Party cronies in House Speaker Sam Rayburn’s office when he was asked to return a call to Steve Early, who asked him to come at once to the White House. The plainspoken Missourian exclaimed, “Jesus Christ and General Jackson!” He grabbed his broad-brimmed white hat and was driven at speed from the Capitol to the White House. The first lady placed her hand gently on Truman’s shoulder and said, “Harry, the President is dead.”

After taking a few moments to absorb the news and its implications, Truman asked, “Is there anything I can do for you?” He never forgot her “deeply understanding” reply: “Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.”

Abruptly, Truman was thrust into the role of America’s leader in World War II, which would rage on for almost another five months until the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945. He had been left in the dark by FDR about international affairs, and had to be hastily briefed about the development of the atomic bomb. On April 13, Truman would tell reporters, “When they told me yesterday what had happened (Roosevelt’s death), I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.”

His cabinet members rushed to the White House on April 12. Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., was already there. The first lady notified her four sons of their father’s death, ending her message: “He did his job to the end, as he would want you to do. Bless you all, and all our love.” Elliott was with the Army Air Forces in England, James with the Marine Corps, and Franklin, Jr., and John with the Navy. After Truman was sworn in as the 33rd president, Mrs. Roosevelt asked him if she could use a government plane to go to Warm Springs; he agreed. As she walked, tall and erect, to the White House limousine, some newspaperwomen were standing beneath the portico. “A trooper to the last,” whispered one.

On the morning of Friday, April 13, a hearse carrying FDR’s flag-draped bronze coffin drove from the Little White House to the Warm Springs railroad station. Patients in wheelchairs and on crutches watched, and the streets were lined with soldiers from nearby Fort Benning, home of the 82nd Airborne Division. The hearse was followed by the Fort Benning band and a 100-man color guard carrying carbines and company flags with black streamers. At the station siding, surrounded by thousands of silent Georgians, eight soldiers loaded the coffin aboard a modified presidential train. A raised catafalque had been placed in the last parlor car so that the coffin could be seen by onlookers as it proceeded northward. It was illuminated at night and could be seen from a great distance.

The train moved out slowly. During its sedate 800-mile journey, an estimated two million people gathered to bid farewell to their longest-serving leader. All day and the following night, they stood on rural station platforms, at road junctions, in fields, and in hamlets—farmers, sharecroppers, storekeepers, housewives, and children. In Georgia, four black women knelt at the edge of a cotton field with their hands clasped in prayer. The train rumbled on through the tobacco farms of the Carolinas. At a country depot in South Carolina, Boy Scouts sang the Anglican hymn “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” and when the train halted briefly to take on water or stores, local church choirs sang “Rock of Ages” and “Abide With Me.”

That day, the veteran United Press correspondent Merriman Smith sat in his drawing room, too drained to dictate and thinking of the prayer Roosevelt had composed for the long-awaited Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944: “Some will never return. Embrace these, Father, and receive them, Thy heroic servants, into Thy kingdom.”

As the presidential train wound northward during the night of April 13-14, Eleanor Roosevelt lay in her berth, unable to sleep. She raised the window shade and looked in amazement at the solemn faces of ordinary people standing vigil in the darkness. The first lady remembered the lines of “The Lonesome Train,” a poem written on the death of President Abraham Lincoln 80 years before: “A lonesome train on a lonesome track / Seven coaches painted black / A slow train, a quiet train / Carrying Lincoln home again…”

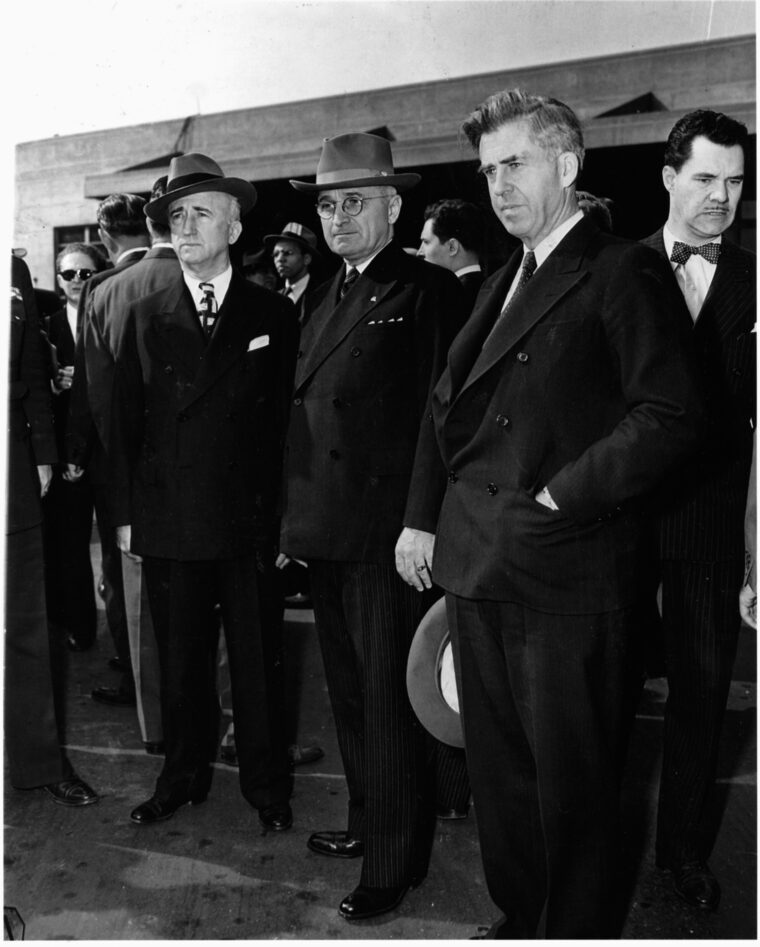

Early on the morning of Saturday, April 14, the train clattered across the Potomac River and backed into Washington’s Union Station. It was met by President Truman, cabinet members, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, congressmen, and representatives of the judiciary.

The funeral cortege passed through the streets of the nation’s capital on the morning of Saturday, April 14. Thousands of men, women, and children packed the sidewalks along Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues, yet the city was eerily quiet. The sky was crystal clear, and the sun grew warmer. Sweat ran down the faces of the steel helmeted soldiers lining the streets. Small boys perched in spring-green trees along the avenues, and heads clustered in the windows of federal buildings. Mothers led small children through the crowds. Everyone spoke in low voices. They listened and waited, and many sobbed.

Then, faintly at first, came the thump-thump-thump of muffled drums and the slow wail of a funeral march. With silver horns flashing in the sunlight, the U.S. Marine Corps Band marched by, followed by a battalion from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. The cadet officers carried drawn swords, and the midshipmen shouldered rifles. Next came a field artillery battalion, the soldiers sitting stiffly in their gun carriers and followed by trucks towing howitzers. Marching behind them were black artillerymen, a Navy band and battalion of sailors, and a battalion of Marines, sailors, and members of the Women’s Army Corps.

At last came six big gray horses in brightly polished harnesses pulling an artillery caisson carrying the president’s flag-draped coffin. It was followed by a bridled, riderless Army horse with reversed stirrups, traditional symbol of a fallen warrior. Then came an all-services color guard carrying the President’s flags, and cars containing cabinet members and other government officials. Movie cameramen perched atop trucks wove along the line of march. The crowds were hushed. A short time later at the White House, Roosevelt’s coffin lay in the East Room between the tall portraits of George and Martha Washington. There, at the close of another bloody war, almost 80 years to the day, the body of President Lincoln had also lain.

The 4 pm White House funeral was brief and simple. It opened with the old Anglican hymn “Faith of our Fathers” and included a short reading from President Roosevelt’s first inaugural address. Mrs. Roosevelt remained calm, but the frail Harry Hopkins, FDR’s trusted transatlantic emissary, wept uncontrollably. The rite was attended by all of official Washington, military and civilian. The senior representatives of American allies were the vigorous Canadian prime minister William L. Mackenzie King; the dour Soviet ambassador to the United States, Andrei Gromyko; and the dashing British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, representing Prime Minister Churchill. The stalwart British leader who had worked closely with the American President since before the Pearl Harbor attack had received the shattering news early on the morning of April 13. “I felt as if I had been struck a physical blow,” said Churchill. “My relations with this shining personality had played so large a part in the long, terrible years we had worked together. Now they had come to an end, and I was overpowered by a sense of deep and irreparable loss.”

He went to the House of Commons at 11 that morning and paid tribute to “our great friend.” Churchill spoke of the 1,700 messages that had passed between them during the war, of their nine meetings, and of the 120 days of close personal contact with FDR and his family. “There never was a moment’s doubt, as the quarrel opened, upon which side his sympathies lay,” said Churchill.

It was in this speech that the prime minister described FDR’s Lend-Lease program as “the most unselfish and unsordid financial act of any country in all history.” The British leader concluded, “For us, it remains only to say that in Franklin Roosevelt there died the greatest American friend we have ever known, and the greatest champion of freedom who has ever brought help and comfort from the New World to the Old.” After the eight-minute session, the prime minister proposed that Parliament adjourn out of respect for FDR. It was an unprecedented parliamentary gesture on the occasion of the death of a foreign head of state.

That day, Churchill sent messages to Mrs. Roosevelt, Harry Hopkins, and the new U.S. president, Truman. The prime minister told Eleanor, “As for myself, I have lost a dear and cherished friendship which was forged in the fire of war. I trust you may find consolation in the magnitude of his work and the glory of his name.”

Churchill’s first impulse had been to attend Roosevelt’s funeral, and he ordered a plane to stand by. But, he reported later, “much pressure was however put on me not to leave the country at this critical and difficult moment, and I yielded to the wishes of my friends.” Several key ministers were out of the country, critical debates and a tribute to FDR were scheduled for the following week in Parliament, and the prime minister was expected to accompany King George VI at a memorial service for the American President at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

The impressive service was attended by the royal family and government leaders, and Churchill wept copiously. When the prime minister eulogized Roosevelt in the House of Commons on the afternoon of April 17, the historic building was packed to the steps and doors.

On the night of April 14, in a steady downpour, the 17-car presidential train rumbled out of Washington’s Union Station and rolled through Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and into New York state to the Hudson Valley. Again, thousands of mourners stood silently on station platforms and at rural crossings to watch the lighted funeral car pass by. The President had said nine months before, with the Allied armies on the road to victory, “All that is within me cries to go back to my home on the Hudson River.” Now he was going home.

On the morning of Sunday, April 15, the spring sun brightened the fieldstone ancestral Roosevelt manor house in the little town of Hyde Park on the eastern bank of the Hudson, 10 miles north of Poughkeepsie. In the rose garden near the handsome, weathered old house where the President had been born on January 30, 1882, and played as a child, a grave had been dug in the lawn.

Around the lawn, with their backs to the surrounding 15-foot-tall cedar hedge, beribboned Army, Navy, and Marine Corps veterans of the European and Pacific theaters stood at attention that morning. A little group of Roosevelt’s neighbors stood behind the flower-laden bier. Gazing at the open grave and a flowering lilac bush beyond the hedge, FDR’s secretary, William Hassett, was reminded of the opening line of Walt Whitman’s tribute to Lincoln, “When lilacs last in the dooryard bloomed,” and lines from his “Drum-Taps,” “Hush’d be the camps today / And soldiers let us drape our war-torn weapons, / And each with musing soul retire to celebrate / Our dear commander’s death.”

Heralded by the throb of muffled drums, the funeral cortege began its march toward the gravesite at 10 am The column was led by the band of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, followed by a battalion of cadets in their distinctive War of 1812 uniforms of gray tunics, white trousers, and crossbelts. The cadet officers carried drawn sabers. They marched in threes through lanes of Army troops, sailors, and Marines in measured cadence to the strains of Chopin’s Funeral March.

Drawn by seven brown horses, the caisson bearing the flag-draped coffin followed. Then came the riderless steed led by a black soldier. The President’s family followed in two sedans. The West Point band struck up “Nearer My God to Thee,” the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and “Hail to the Chief.” FDR’s little black Scottish terrier, Fala, rolled in the grass at the feet of Margaret Suckley.

In front of the grave, black-veiled Eleanor Roosevelt stood between her daughter, Mrs. Anna Roosevelt Boettiger, and second oldest son, Brig. Gen. Elliott Roosevelt, who had flown home from England for the funeral. A few paces to the rear, the first lady’s four daughters-in-law struggled to emulate her stoic composure. Near the Roosevelt family stood Truman, his wife, Bess, and daughter, Margaret. Truman’s eyes blinked behind his thick horn-rimmed glasses, and his jaw was clenched as the assembly recited in unison the Lord’s Prayer. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson stood next to Canada’s Mackenzie King.

The coffin was borne into the rose garden through an archway in the cedar hedge by eight soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines. As FDR’s body was gently lowered into the grave, the 78-year-old Reverend W. George Anthony, white-haired rector of St. James’s Episcopal Church in Hyde Park, where the President and his father had served as vestrymen, read the committal words from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. With his surplice fluttering in the breeze, he intoned, “Now the laborer’s task is o’er; now the battle day is past…. Father, in Thy gracious keeping, leave us now our brother sleeping.” Three volleys from a West Point rifle squad cracked over the grave, and Fala barked sharply.

Secretary of Commerce Henry A. Wallace, FDR’s former vice president, watched Eleanor Roosevelt cross herself as she turned away from the grave and said, “God rest his soul.” Looking at the lilacs and listening to the birds singing, Tom Conley, an old friend of the late President, said, “He would have liked this. He always loved clear, crisp spring days. He loved anything that had life.” After the mourners had filed away, local workmen began to fill in the grave. A lone figure returned to watch. It was Eleanor Roosevelt. She would join her husband there 17 years later .n

Author Michael D. Hull resides in Enfield, Connecticut. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History.

All gave some. FDR gave all.