By Mason B. Webb

Besides being a destroyer of lives and cities, war also destroys precious works of art and the ancient monuments of civilization. But if the enemy is holed up in a 1,000-year-old abbey or entrenched outside a palace or museum filled with precious paintings and sculpture, how is one destroyed without harming the other?

This was the dilemma facing Allied armies after invading Italy, arguably the most art-rich country in the world. In what was surely one of the most unusual acts of benevolence in the history of warfare, the Allied armies in Italy put together special teams of experts in art and architecture and sent them into the front lines to brief combat commanders on the vulnerable treasures ahead of them with a plea to spare, if at all possible, the collections.

This was the dilemma facing Allied armies after invading Italy, arguably the most art-rich country in the world. In what was surely one of the most unusual acts of benevolence in the history of warfare, the Allied armies in Italy put together special teams of experts in art and architecture and sent them into the front lines to brief combat commanders on the vulnerable treasures ahead of them with a plea to spare, if at all possible, the collections.

Of course, not all artistic and architectural treasures were spared. The 1943 Allied bombing of the ancient Benedictine abbey atop Monte Cassino is one example of where military exigencies took precedence over preservation. But, for the most part, the vast bulk of Italy’s irreplaceable works of art managed to survive the war––and not by luck.

For her engaging and highly original work, The Venus Fixers: The Untold Story of the Allied Soldiers Who Saved Italy’s Art During World War II (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 2009, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.00), Italian-born journalist Ilaria Dagnini Brey was granted access to private archives that few other writers have seen and goes into great detail to document the heretofore unsung work of these specialists.

A presidentially appointed American commission known as the Second Roberts Commission was set up specifically to deal with the immense problems that a preservation program in an active war zone presented. The initiative, as one general put it, was “without historical precedence in any military campaign.”

Much of Brey’s book is devoted to the city of Florence, the former home of many of the world’s finest artists and a repository to many of mankind’s greatest artistic achievements. The author writes, “For nearly four years before the Allied air raid [of March 11, 1944], the city’s celebrated church facades had been walled in by sandbags, their windows boarded with timber. Lorenzo Ghiberti’s bronze doors, praised by Michelangelo as ‘truly worthy of being the Gates of Paradise,’ had been removed from the Baptistry of Saint John, and the ancient octagonal building now stared as if from empty sockets at the cathedral in front. Statues, shrouded in plastic and cloth, had disappeared beneath bizarre-looking brick domes, and the whole city seemed like an infirm body wrapped in bandages for wounds yet to be inflicted.”

The men responsible for saving places like Florence––a motley group of art historians, curators, professors, and passionate amateur experts—were known as “Monuments Officers” or the “Venus Fixers.” Their efforts augmented those of local curators who had been working furiously for years to keep the irreplaceable treasures out of harm’s way by hiding paintings in cellars and tombs.

Often working as shells exploded around them, the Venus Fixers collaborated with the local curators to shore up tottering palaces and cathedrals, safeguarded works by Michelangelo and Botticelli and others, prevented looting by enemy and Allied soldiers alike, and, in one case, even blocked a Nazi convoy of stolen paintings bound for the notorious art thief Hermann Göring’s birthday celebration.

The Venus Fixers is a magical work that anyone with the slightest interest in the fate of art treasures and humanity in wartime must read.

Jack Toffey’s War: A Son’s Memoir, by John J. Toffey IV, Fordham University Press, New York, 2008, 269 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography index, hardcover, $29.95

Jack Toffey’s War: A Son’s Memoir, by John J. Toffey IV, Fordham University Press, New York, 2008, 269 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography index, hardcover, $29.95

In 1996, John J. Toffey IV made a remarkable discovery: the letters that his father, Jack Toffey, a battalion commander, had written home during the war. The letters launched the younger Toffey on a journey to learn more about his father, the war, and its impact on hometown Ohio.

Called up during the mobilization in 1940, Jack Toffey was a junior officer in the 44th Infantry Division. Over the course of the next few years, Toffey was transferred to the 9th Infantry Division, promoted to lieutenant colonel, given command of a battalion, and participated in the invasion of North Africa, where he was first wounded.

Toffey had recuperated by the time the 9th was picked to be one of the divisions going into Sicily, and he was made executive officer of one of the regiments. A short time later, after the invasion of mainland Italy, he was put in command of an artillery battalion. He then requested a transfer to the 3rd Infantry Division, a request that was granted, and he was back to commanding a battalion of foot soldiers.

The invasion of Anzio, an “end run” around the stalemate at Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line in January 1944, would prove to be Toffey’s demise, however. In March, he was made regimental executive officer of the 7th Infantry Regiment which, ordinarily, would have been a respite from the direct dangers of combat. But Toffey was not the kind of officer who took shelter far behind the front lines.

After the Allied breakout from the beachhead at the end of May, Toffey was in his favorite place, with the men at the front. Two days before Rome was captured, while coordinating an attack, he was killed by enemy fire.

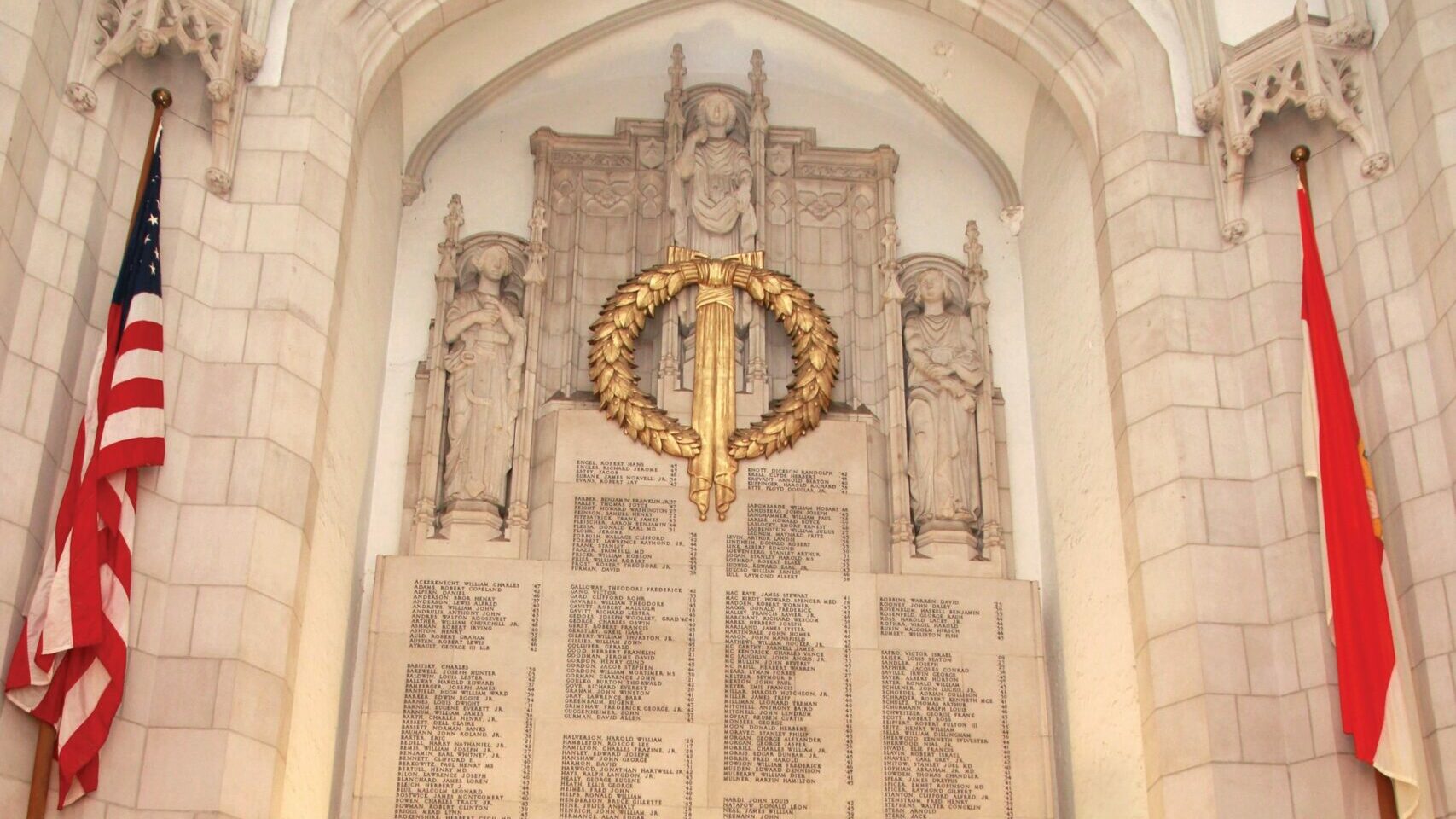

Jack Toffey, along with 7,861 other American soldiers, is buried beneath a simple, white marble cross at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery at Nettuno, Italy, next to Anzio. And now, thanks to his son’s moving and highly personal book, Jack Toffey has an epitaph to his service and his sacrifice. No man could ask for a finer one.

Military Sun Helmets of the World, by Peter Suciu (with Stuart Bates), Service Publications, Ottawa, Canada, 2009, 93 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95.

Military Sun Helmets of the World, by Peter Suciu (with Stuart Bates), Service Publications, Ottawa, Canada, 2009, 93 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95.

The sun helmet, or “pith” helmet as it is commonly known, has long been the choice of headgear for archaeologists, explorers, and big game hunters. And also of the military.

As author Peter Suciu notes, “The helmets have a civilian origin and were gradually adopted by the military, but even to collectors of military headdress the sun helmet is not a combat item. While certainly not part of a dress uniform, sun helmets are the sort of ‘other helmet’ to many collectors. However, the sun helmet’s history on the battlefield is a long one, and while offering little or any ballistic protection, the sun helmets provided adequate protection from the rays above, and that was, after all, its intended purpose.”

In his engaging work, lavishly illustrated by drawings and color photos of helmets in his own extensive collection, Suciu begins with the history of the helmet as used by the British Army in the 19th century in some of the hottest regions in the world, Abyssinia, India, Zulu country, and more.

Suciu also delves into the use of the helmet by other nations, including France, Italy, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Japan, the U.S., and Germany (images of Afrika Korps troops in sun helmet are iconic).

Even if one is not a collector of headgear, Suciu’s book makes for fascinating reading.

Forgotten Weapon: U.S. Navy Airships and the U-Boat War, by William F. Althoff, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 432 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.00.

Forgotten Weapon: U.S. Navy Airships and the U-Boat War, by William F. Althoff, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 432 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.00.

Here’s another book on another offbeat, but no less interesting subject—airships.

Commonly called “blimps,” these bulbous, slow-moving denizens of the air seem quaint and almost comical today. In an era of computers, missiles, spy satellites, and electronic warfare, the Navy’s nonrigid airship seems an anachronism, a 20th-century platform predestined for obscurity.

Indeed, the widespread ignorance today of the airship’s existence and role in World War II is remarkable, and it is easy to dismiss it as some sort of military aberration.

From 1935 to 1945, nonrigid airships were operated by the U.S. Navy to keep an eye on German submarines that were prowling along the Eastern Seaboard. Once spotted, the U-boats became targets for air and surface craft to attack them. U-boat commanders learned to steer clear of the blimps.

Many have questioned the military effectiveness of the blimp force, however. Only one is known to have assisted in the sinking of a U-boat and possibly damaging three others. Althoff candidly acknowledges this and questions the blimps’ limited contribution to the overall war effort. As he writes, “Was [the airship] of sufficient value to offset the expenditure in industrial capacity, personnel, airbases, and special facilities––resources better applied elsewhere?” Could the 7,000 Navy personnel assigned to airship duties have been better utilized in other, more offensive roles?

The Navy must have agreed for, with victory and the advent of more advanced technologies, the airship went the way of the horse cavalry, its service no longer needed for the conduct of modern military operations.

Author Althoff has done a superb job in giving the airship its due by crafting this entertaining and informative volume. Found within its 432 pages are scores of photos that detail the design, construction, and operation of these “gas bags,” plus a text that provides readers with everything they never knew about this unusual craft.

Although the blimps’ contributions to victory were marginal, Althoff’s fine book is a loving tribute to the airships and the men who flew and maintained them.

Battle of Surigao Strait, by Anthony P. Tully, University of Indiana Press, Bloomington, 2009, 329 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.95.

Battle of Surigao Strait, by Anthony P. Tully, University of Indiana Press, Bloomington, 2009, 329 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.95.

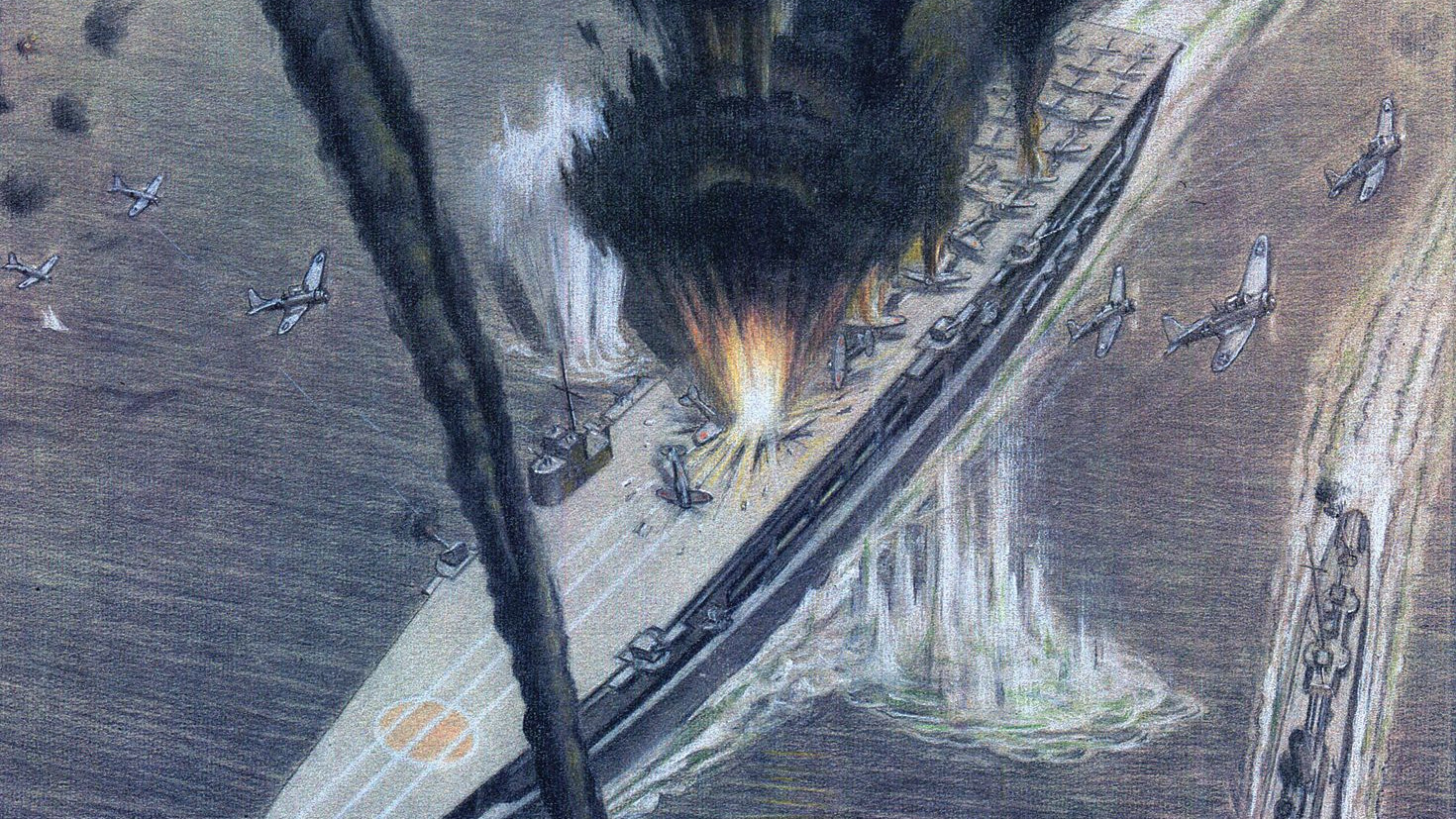

Anthony Tully gave the world a stunning portrait of the Battle of Midway in his (and co-author Jon Parshall’s) Shattered Sword. He reprises that achievement with Battle of Surigao Strait, a finely wrought account of the epic naval engagement of Leyte Gulf that lasted from October 23-26, 1944.

During those three crucial days, the Imperial Japanese Navy, in its final major effort of the war, attempted to stop the American invasion and liberation of the Philippines. What ensued was an all-out slugfest on the high seas and the last time battleships would fight each other in a surface engagement.

With dramatic clarity and a fine prose style, Tully gives the reader an hour-by-hour, blow-by-blow description of the conflict in which two Japanese fleets of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers threw themselves in a fanatical charge against an American fleet that included five battleships that had been resurrected after the debacle at Pearl Harbor three years earlier.

Tully’s account also goes far to correct myths and inaccurate versions of the battle found in some earlier books. He sheds new light on tactical and staff decisions that have puzzled many historians. Some of his revisions may appear as drastic as they will be controversial, but all are backed by solid evidence uncovered after years of careful research.

Making extensive use of unpublished records (such as never-before-translated Japanese records) and survivor testimonies, Tully lifts the cloak of ambiguity and mystery that has shrouded the events of that fateful night and produces a truly new reassessment of one of the war’s most pivotal naval clashes.

Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany’s Greatest Battleship, by Niklas Zetterling and Michael Tamelander, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2009, 320 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany’s Greatest Battleship, by Niklas Zetterling and Michael Tamelander, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2009, 320 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Another outstanding book about naval warfare is Bismarck, in which Swedish authors Zetterling and Tamelander recount the British effort to rid the seas of the German battleship that was the most powerful warship of its day. Launched in February 1939, Bismarck was an engineering and technological masterpiece: a displacement of over 41,000 tons, nearly the length of three football fields, bristling with eight 15-inch, radar-guided guns, and a propulsion system capable of producing a top speed of 31 knots.

The British rightly worried that, unrestrained, the enemy ship could devastate shipping in the Atlantic and so, in the spring of 1941, the order was given by the Admiralty to the Home Fleet: Sink the Bismarck!

On her maiden combat voyage, Bismarck left the Baltic Sea port of Gotenhafen, Poland, on the night of May 18, 1941, to raid American Lend-Lease convoys crossing the North Atlantic but was soon discovered while passing through Norwegian waters. The pride of the Royal Navy, the battlecruiser HMS Hood, with the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales, was dispatched from Scapa Flow to intercept her. But finding the behemoth on the high seas proved to be a major challenge.

At last Bismarck was spotted near Iceland, and a long chase ensued. On May 24, Bismarck and her accompanying heavy cruiser, Prinz Eugen, were confronted off the coast of Greenland, but the hunters quickly became the hunted. Bismarck utterly destroyed Hood within minutes, and only three of her 1,400-man crew survived. Prince of Wales was also badly damaged but stayed afloat.

The two German ships then sailed farther south but the Home Fleet was determined to stop them. Four capital ships, including the battleships King George V and Rodney, supported by aircraft from the carriers Victorious and Ark Royal, were sent out to find them.

As luck would have it, the aircraft found the Bismarck alone, far from home, and unguarded by Prinz Eugen, and a direct hit by an aerial torpedo knocked out her rudder. Unable to maneuver, Bismarck became easy prey for the trailing British task force, and nearly 2,000 men went down with her.

Based on official records and accounts from survivors of these titanic battles and the latest historical discoveries (including the recently discovered wreck of Bismarck), the book is written in a real-time, you-are-there style that conveys all the anxiety of actual combat at sea. Highly recommended.

No Better Place to Die: The Battle for La Fière Bridge, Ste. Mère-Eglise, June 1944, by Robert M. Murphy, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, 2009, 272 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

No Better Place to Die: The Battle for La Fière Bridge, Ste. Mère-Eglise, June 1944, by Robert M. Murphy, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, 2009, 272 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

Anyone who visits the French village of Ste. Mère-Eglise in Normandy probably will come across a street named “Rue Robert Murphy,” and the visitor is likely to ask, “Who is Robert Murphy?”

The answer is held in this outstanding memoir by Murphy, one of the Pathfinders from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, who parachuted into France in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944.

Pathfinders had one of the most difficult and dangerous jobs in Operation Overlord, for it was they who were assigned the task of arriving before the main wave of transport planes and lighting the pitch-black drop zones so the transport pilots would know when and where to release their human cargo.

Murphy details the 82nd’s mission: to capture the vital crossroads town of Ste. Mère-Eglise and seize the bridge over the Merderet River at La Fière to prevent a German counterattack from disrupting the amphibious landings at Utah Beach. Of crucial importance, the bridges and raised causeways at La Fière and nearby Chef-du-Pont were the key to Allied success on D-Day, for they provided the U.S. 4th Infantry Division with its only dry route inland from Utah Beach, as the Germans had flooded the surrounding countryside. The descriptions of the fierce fighting for the bridge at La Fière are some of the most compelling ever written.

Murphy’s book is filled with more than just his personal exploits. He has also included accounts and memoirs from many of his comrades, plus supporting documents that give a fuller picture of what the 82nd accomplished on D-Day and the days after.

Sadly, Murphy passed away in 2008, but the accounts of his and his fellow parachutists’ contributions to victory in Europe will live forever.

Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945, by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2009, 324 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940-1945, by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2009, 324 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

The Mediterranean Sea was the most hotly contested body of water in World War II. As the maritime crossroads where Europe, Asia, and Africa meet, more major naval actions were fought in the “Middle Sea” than in either the Atlantic or Pacific.

Despite its importance, remarkably little has been written about the subject, and what exists is largely one-sided and outdated. O’Hara’s fresh look at the naval war that raged across the Mediterranean from Gibraltar to Greece analyzes the actions and performances of the five major navies––the British, French, Italian, German, and American––that fought there during the lengthy campaign and objectively examines the national imperatives that drove each combatant nation’s maritime strategy.

O’Hara’s work avoids the old myths that haunt this theater of war, such as Great Britain enjoying a moral advantage over Italy, or the French being Germany’s puppet, or the North African campaign significantly contributing to the eventual Allied victory.

The author documents how the British Royal Navy, despite brilliant victories, was bled white in a campaign with questionable strategic goals; how Italy followed its own naval strategy, much to the frustration of its German ally; and how the French Navy was the strength of the independent French state, and how it fought the Allies and rejected the Axis to maintain that independence.

Unlike other works on the subject, Struggle for the Middle Sea provides a complete history of the entire five-year campaign from all perspectives and covers Germany’s largely unknown and extremely successful struggle to employ sea power in the Mediterranean after the Italian capitulation.

Hitler’s Pre-Emptive War: The Battle for Norway, 1940, by Henrik O. Lunde, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2009, 590 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Hitler’s Pre-Emptive War: The Battle for Norway, 1940, by Henrik O. Lunde, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2009, 590 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Little has been published in the U.S. about Nazi Germany’s invasion of Norway, so this book comes as a refreshing and definitive account of that campaign.

In April 1940, a month before his armies crossed the borders of France, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg, Hitler launched an unprovoked invasion of Norway, an invasion even his general staff initially opposed as being “lunatic” and of little military value.

The unexpected, 62-day war in Norway turned out to be a stunning success for the Germans. It was the first time in history that land, sea, air, and specialized forces were fully involved in a coordinated campaign in another country. It was also the first direct clash between German and British forces and became a testing ground for the innovations in equipment and doctrine developed since the Great War.

For example, in Norway the effect of air power on both land and naval operations caused a fundamental shift in how this new weapon was perceived. The campaign also saw the first use of airborne troops to seize airfields and key objectives far behind enemy lines.

As Lunde, a retired, Norway-born American Army officer, points out, many of the problems on the Allied side were ones that perpetually face military planners and operators. The campaign revealed serious deficiencies in Allied command structure, inter-Allied cooperation and coordination, and the unfortunate effects of strong individuals unwilling to compromise.

The Allies also failed to devise an effective strategy until it was too late. Meanwhile, the Germans held the initiative and, by the end of the campaign, some 5,000 of their troops around Narvik were able to hold off some 30,000 Allied and Norwegian troops until the Allies were compelled to withdraw.

Lunde has crafted a brilliant, long-overdue study of this early, virtually unknown campaign and one that deserves a wide readership.

Water in My Veins: How a Pauper Helped Save a President, by Ted Robinson, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2009, 455 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $26.00.

Water in My Veins: How a Pauper Helped Save a President, by Ted Robinson, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2009, 455 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $26.00.

By now, almost everyone is familiar with the wartime saga of Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy and PT-109––how, in the roiling waters around Guadalcanal, Kennedy’s boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer and how the young officer, in spite of his own injuries, continually rescued members of his crew.

Now comes an excellent memoir by Ted Robinson, possibly the last living Navy officer who personally knew the man who would go on to become the 35th President of the United States. Growing up in a poverty-stricken family in New York during the Great Depression, Robinson went on to graduate from Duke University and joined the Navy a few months before Pearl Harbor to “see the world.” Little did he know the fate that awaited him.

As a young officer assigned to a PT-boat squadron, Ensign Robinson eventually wound up in the Pacific and at a base on the island of Tulagi, near Guadalcanal in the Solomons. When the “Tokyo Express,” a convoy of Japanese warships full of reinforcements, came roaring down The Slot on the night of August 1, 1943, the PT boats were sent out to intercept them. Robinson’s boat, PT-159, was one of those involved in the harrowing action. In the melée, Kennedy’s boat was smashed and the survivors dumped into the water.

Robinson was on one of the two PT boats that went out to search for and rescue Kennedy and his crew in the days after the attack, and was the person to whom the natives delivered the famous coconut on which Kennedy had carved the news that he and 10 other crewmen of PT-109 were still alive. Ensign Robinson was also involved in the operation to pick up Kennedy and the other survivors from their island hideout and bring them back to safety.

While there is much more to be said about this book, suffice it to say that Water in My Veins is a very entertaining read.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments