By Al Hemingway

On the morning of March 31, 2004, in the city of Fallujah, Iraq, the unmistakable sound of automatic weapons fire could be heard. A Mitsubishi Pajero, carrying four Americans, was suddenly ambushed by insurgents. Driver Wes Batalona unsuccessfully tried to make a U-turn in the crowded streets, but was gunned down by AK-47 bullets that ripped through the vehicle.

The car spun out of control and rear ended another. It was over in a matter of seconds. The four men, all employees of Blackwater USA, a private military contractor, had been slain. That night on the evening news, the charred and mutilated bodies of two of the men were hung from an old bridge to be viewed by all.

The incident was the catalyst that sparked two separate battles of Fallujah, after which American soldiers and Marines would spend months clearing the city of known terrorists residing there. For the leathernecks, it would be some of the heaviest urban fighting since the Battle of Hue City in Vietnam in 1968. In Operation Phantom Fury: The Assault and Capture of Fallujah, Iraq (Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 320 pp., index, photos, maps, $30.00, hardcover), retired Marine Colonel Dick Camp, a Vietnam veteran and Khe Sanh survivor, delivers an intriguing account of the two major campaigns to drive the terrorists out of the city.

The incident was the catalyst that sparked two separate battles of Fallujah, after which American soldiers and Marines would spend months clearing the city of known terrorists residing there. For the leathernecks, it would be some of the heaviest urban fighting since the Battle of Hue City in Vietnam in 1968. In Operation Phantom Fury: The Assault and Capture of Fallujah, Iraq (Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 320 pp., index, photos, maps, $30.00, hardcover), retired Marine Colonel Dick Camp, a Vietnam veteran and Khe Sanh survivor, delivers an intriguing account of the two major campaigns to drive the terrorists out of the city.

Located approximately 40 miles west of Baghdad, Fallujah was a thriving metropolis prior to the war, with a population of more than half a million residents. Situated in the infamous Sunni Triangle, where the former dictator Saddam Hussein enjoyed his greatest support while in power, it is also called the “city of mosques” because of the 200 religious structures that dominate the city’s landscape.

Initially, military leaders suggested that the Bush administration proceed with caution. Lt. Gen. James T. Conway, 1st Marine Expeditionary Force commander, did not want it to appear that the United States was attacking out of revenge and thus lose the support of the rest of the civilian population. “Once you commit you have to stay committed,” he remarked.

Unfortunately, the pleas of Conway and other commanders fell on deaf ears as Ambassador L. Paul Bremer and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld pressed U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, in charge of all coalition forces in Iraq, to proceed immediately. President George W. Bush, they said, “wanted heads to roll.”

Although they felt that the “timing was not right,” military personnel obeyed their civilian leaders and initiated Operation Vigilant Resolve, the First Battle of Fallujah, in April 2004. The campaign was a dismal failure. Although coalition troops fought aggressively and bravely, they were withdrawn before the insurgents had been driven from the city. The remainder of the task fell to the newly formed Fallujah Brigade, which later disbanded and, in an unbelievable turn of events, surrendered all of its weapons to the terrorists. Twenty-seven Americans paid the supreme sacrifice, and another 90 were wounded in vain.

This prompted the Second Battle of Fallujah in November 2004, code-named Operation Phantom Fury. Once again, American soldiers and Marines stormed the insurgents’ stronghold and, as before, infantrymen had to endure their worst nightmare—going house to house to ferret out the enemy. For more than a month, the terrorist stronghold was the scene of bloody combat as American and Iraqi troops slowly cleared the city of Islamic extremists. To make matters worse, the enemy used numerous mosques within the town as observation points and storage facilities for weapons and supplies. Despite this, Allied forces were victorious, although at a cost of 63 killed and more than 500 wounded.

The author focuses on the friction between the civilian and military camps that produced the first Fallujah fiasco. Instead of listening to their advice, the Bush administration typically rushed in headlong before carefully examining all options and attacking at a time that would be more beneficial to the coalition forces. As in past conflicts, whenever civilian leaders insist upon a disastrous course of action, it is the American servicemen who have to pay for their gross errors in judgment.

In the end, however, the fighting men managed to achieve victory, however costly. Although the coalition troops faced a determined foe bent on their destruction, the enemy was no match for the soldiers and Marines. As Camp concludes, the terrorists attempted to “turn the city into a fortress to defeat the Americans—and they lost.”

An Artist in Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of General James Wilkinson by Andro Linklater, Walker Publishing, New York, 2009, 392 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $27.00, hardcover.

An Artist in Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of General James Wilkinson by Andro Linklater, Walker Publishing, New York, 2009, 392 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $27.00, hardcover.

Maryland-born James Wilkinson was described by his friends as congenial, friendly, and charming. These attributes catapulted him into the limelight during the Revolutionary War, where he soon caught the attention of most of the officers of the Continental Army, including Commander in Chief George Washington, and was appointed the youngest general at the age of 20. Wilkinson’s charismatic behavior and his penchant for delivering a convincing argument would prove beneficial to him in ensuing years, when the outwardly patriotic officer turned into an undercover agent for the Spanish government.

In his new biography, author Andro Linklater delivers an absorbing account of his double life and the reasons why Wilkinson chose such a deceitful path. Wilkinson learned at an early age about the class system. Being from the upper crust of society would always remain an important part of his life. He attended medical school and set up practice in Baltimore, but after he observed the local militia in a parade, he felt the “strongest inclination to military life.”

Wilkinson was simply known as Agent 13 to the Spanish. After his proposal to have Kentucky become part of Spain’s western empire failed, he still continued to receive a pension from the Spanish government. When he was appointed head of the U.S. Army after General “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s untimely death, his clandestine relationship with Spain resumed. Wilkinson tried in vain to stop the Lewis and Clark expedition, informing Spanish authorities, who quickly dispatched a large patrol to scour the territory and arrest the explorers for trespassing on Spanish soil.

Wilkinson’s biggest challenge occurred in 1805, when he was accused of collaborating with ex-Vice President Aaron Burr to provoke a war with Spain and create a new country in the territory of the Louisiana Purchase, with the shifty Burr as its ruler. Some believed that Wilkinson was the mastermind behind the scenario. When Burr’s devious scheme was uncovered, by none other than Wilkinson himself, he was promptly arrested and brought to trial. In true Wilkinson fashion, his flowery testimony and uncanny ability to shift the blame onto others worked in his favor, and all charges against him were dismissed.

Wilkinson’s dismal performance during the War of 1812 was enough for the administration to remove him from command. Retiring, he traveled to Mexico, where he died a few days after Christmas in 1825. In 1872, the American government tried to bring Wilkinson back to his native country and give him a proper burial, but it was discovered that he had been reburied in a common grave. There was no way of determining which remains were his. The wily Agent 13 remained elusive, nearly 50 years after his death.

Thutmose III: The Military Biography of Egypt’s Greatest Warrior King by Richard A. Gabriel, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2009, 241 pp., notes, index, maps, $29.95, hardcover.

Thutmose III: The Military Biography of Egypt’s Greatest Warrior King by Richard A. Gabriel, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2009, 241 pp., notes, index, maps, $29.95, hardcover.

Some historians have referred to Thutmose III, a pharaoh in the 18th Dynasty, as the “Napoleon of Egypt.” Actually, he was considerably taller than his French counterpart. Historians simply did not take into account that grave robbers had desecrated his tomb and cut off his feet.

Height aside, Thutmose III left behind an incredible legacy. He reigned for 32 years and led 19 expeditions into Canaan and Syria. He was also the father of the Egyptian Navy, constructing a massive shipyard and overseeing the expansion of his fleet. His uncanny ability for military strategy enabled him to transform Egypt into a force to be reckoned with. Under his tutelage, the army underwent some of the most stringent training for its time. The armies he conquered were professionals, unlike Alexander the Great, whose victories were achieved against mostly second-rate armies and third-rate generals.

In spite of his royal upbringing, Thutmose III had two enduring qualities—humility and compassion—that made him popular with his troops. He split the spoils with his soldiers and awarded medals for bravery in battle. He even spared his enemies after they were captured and chose not to kill the civilian population after he had seized their towns or villages.

Although best known for his military ingenuity, Thutmose III was a lover of the arts and sciences. He had a keen interest in botany and ordered his men to retrieve unusual plants and shrubbery he encountered while in strange lands and return them to Egypt to be replanted. He was also fascinated by the curious animal life he saw, especially the elephant, which he studied at great length.

This burning curiosity, along with his other positive attributes, made him popular with the people during his tenure as pharaoh. He was indeed a multifaceted individual, probably one of the greatest rulers Egypt has ever known.

American Military Vehicles of World War I: An Illustrated History of Armored Cars, Staff Cars, Motorcycles, Ambulances, Trucks, Tractors and Tanks by Albert Mroz, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC, 2009, 316 pp., index, photos, illustrations, $45.00, softcover.

American Military Vehicles of World War I: An Illustrated History of Armored Cars, Staff Cars, Motorcycles, Ambulances, Trucks, Tractors and Tanks by Albert Mroz, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC, 2009, 316 pp., index, photos, illustrations, $45.00, softcover.

As the title implies, this is probably the definitive book on all types of military vehicles employed during World War I. It is full of wonderful photographs and drawings of every imaginable kind of motorized vehicle from that era. The front cover has an interesting picture of an Indian motorcycle with a sidecar equipped with a machine gun. Other fascinating photos depict armored cars of all shapes and sizes, ambulances, including a Harley-Davidson dubbed “The Flying Squadron,” and even an electric-powered car that was used in munitions factories to transport artillery shells from one part of the plant to another, and was driven by a female worker.

As Mroz demonstrates, the gas-powered combustion engine, although not new when the war began, became invaluable to troops overseas, as well as on the home front. These rudimentary vehicles—tanks, armored cars, and ambulances—would undergo more changes when the United States found itself involved in World War II a quarter of a century later.

Flotilla: The Patuxent Naval Campaign in the War of 1812 by Donald G. Shomette, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2009, 500 pp., notes, index, maps, illustrations, $38.00, hardcover.

Flotilla: The Patuxent Naval Campaign in the War of 1812 by Donald G. Shomette, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2009, 500 pp., notes, index, maps, illustrations, $38.00, hardcover.

Maryland-born Joshua Barney had an illustrious naval career. In the Revolutionary War he served as a young lieutenant on several warships and was taken prisoner on several occasions, escaping from Old Mill Prison in Devon, England. After the United States obtained its independence from Great Britain, Barney received an officer’s commission in the French Navy. He then commanded a schooner, but his days as a privateer on the high seas did not make him any money. In 1812, when hostilities broke out between Great Britain and America, Barney was made a captain in the fledgling U.S. Navy, and once again he ventured out to do battle with his old adversary.

Barney concocted a plan to defend Chesapeake Bay from the annoying and devastating raids being conducted by the British, who had blockaded the waterway at its narrow entrance at Virginia Capes. Their many incursions were not only lowering morale but also hurting the local economy. Barney envisioned a flotilla of gunboats with drafts so shallow that they could maneuver through the more than 8,000 miles of the bay and its tributary, the winding Patuxent River. With these small vessels he could attack the enemy’s barges when they departed the umbrella of covering fire provided by the fleet positioned at the access to the bay.

Although it looked good on paper, Barney’s plan did not succeed. He did harass the redcoats but he had to abandon his flotilla and destroy most of his fleet. He then linked up with the American Army and fought heroically at the Battle of Bladensburg, but once again had to retreat from the battlefield in the face of overwhelming British forces.

In 2006, a committee was created to erect a memorial to the members of the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla. Their bravery and sacrifice against overwhelming odds should never be forgotten.

Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War by John W. Hall, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2009, 367 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War by John W. Hall, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2009, 367 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Native Americans in the 1820s and 1830s described white American settlers as “a drop of Racoons Grease falling on a new blanket, at first [it] is scarcely perceptible, but in time covers almost the whole Blanket.” During this era, the war chief Black Hawk led the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo tribes in a war against the American government in present-day Illinois and Michigan. The Indians were becoming increasingly agitated about the encroachment of more and more whites onto their land—land that had been promised to them.

Not all the tribes rushed to align themselves with Black Hawk. Many warriors of the Menominee, Dakota, Potawatomi, and Ho Chunk clans linked up with American troops to defeat him. Why did Black Hawk’s fellow Native Americans do this? The reasons were varied, according to the author. Some supported the United States because they envisioned Black Hawk losing anyway. Others had longstanding grievances that they wanted to avenge, and some chiefs thought they could attain political and material gains if Black Hawk’s revolt was crushed.

Although a short campaign, the fighting was bloody, with militia and regulars massacring women and children along with the warriors. The tribes that fought alongside U.S. forces fared no better in ensuing years, as a steady stream of white immigrants moved westward. “Unlike the Indian allies of the Black Hawk War,” writes Hall, “today’s Indian warriors must selectively draw upon a problematic past, but—like their forbears—they continue to serve the United States foremost as a means of serving their own people.”

Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945 by Randall Hansen, New American Library, New York, 2009, 352 pp., notes, index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945 by Randall Hansen, New American Library, New York, 2009, 352 pp., notes, index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Ever since the advent of the airplane, bombing has been a source of controversy. Should indiscriminate carpet bombing or strategic bombing be used? In his new book, historian Randall Hansen examines the stark differences between the British and American approach to this problem during World War II. The English were determined to utilize carpet bombing to bring Germany to her knees. The Americans, on the other hand, were advocates of destroying important military installations to halt production and stop the Nazi war machine.

Then there was the touchy subject of civilian casualties. Does the indiscriminate bombing of a specified region justify the killing and maiming of noncombatants? Many Americans did not think so. To air crews, it was abhorrent to purposely bomb defenseless civilians. Although Great Britain and other countries under the dominance of the Nazi boot had suffered similar atrocities, American forces still felt uncomfortable doing it.

Which strategy prevailed? Captured Nazi architect Albert Speer summed it up best when he told British and American interrogators: “The American attacks which followed a definite system of assault on industrial targets, were by far the most dangerous. It was in fact these attacks which caused the breakdown of the German armaments industry.”

Commanding Lincoln’s Navy: Union Naval Leadership During the Civil War by Stephen R. Taaffe, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 324 pp., notes, index, maps, illustrations, $34.16, hardcover.

Commanding Lincoln’s Navy: Union Naval Leadership During the Civil War by Stephen R. Taaffe, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 324 pp., notes, index, maps, illustrations, $34.16, hardcover.

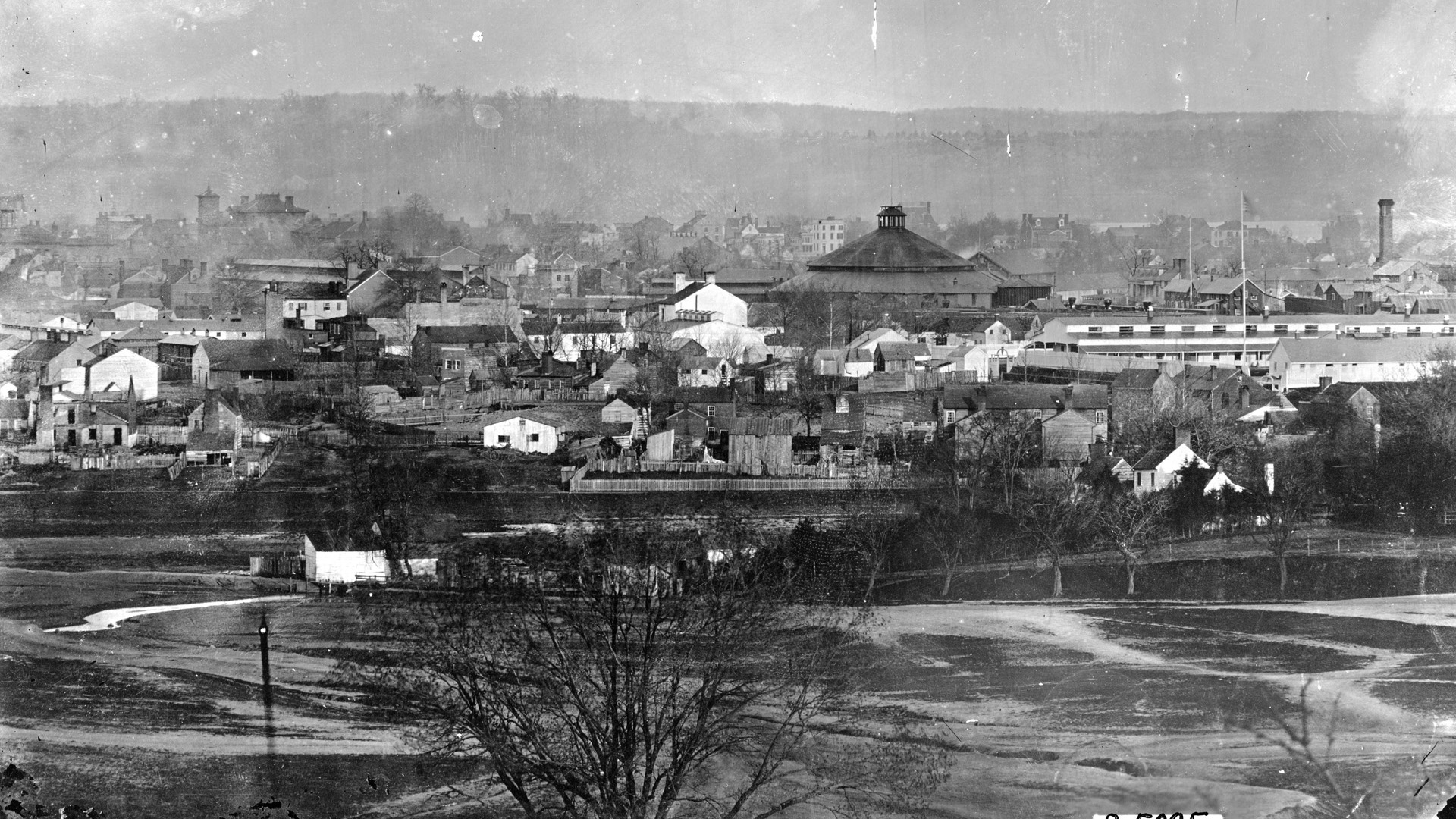

There is no doubt that the Union Navy helped enormously to defeat the Confederacy during the Civil War. “Uncle Sam’s web feet,” as President Abraham Lincoln referred to them, conducted a successful blockade to deprive the Rebels of supplies, sought out Confederate raiding ships that preyed on Northern merchant vessels, and navigated waterways deep into the heart of the South to support the advancing Union armies.

At the start of hostilities in 1861, the Union Navy had a skeleton force of just under 9,000 officers and men to operate a fleet of 42 steam-driven warships. By the end of the conflict in 1865, those numbers had risen dramatically to nearly 58,000 sailors and 650 ships of the line. The man in charge of this near-miraculous conversion was Connecticut-born Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. A friend and political supporter of Lincoln, Welles had a free hand in establishing an impressive seaborne fighting force. Welles made most of his decisions without interference from “Old Abe,” and in most instances he was proven correct.

God’s Battalions: The Case for the Crusades by Rodney Stark, Harper One, New York, 2009, 276 pp., index, bibliography, illustrations, $24.99, hardcover.

God’s Battalions: The Case for the Crusades by Rodney Stark, Harper One, New York, 2009, 276 pp., index, bibliography, illustrations, $24.99, hardcover.

On the outskirts of the French village of Clermont in the year 1095, Pope Urban II delivered a message to the huge crowd assembled there. He spoke of a letter he had received from Emperor Alexius Comnenus of Byzantium telling him of the Islamic invasion that had swept the countryside. In their wake, Comnenus alleged, they had committed unspeakable atrocities upon Christians.

Although Comnenus was Greek, and his brand of Christianity was abhorred by the church, the Pope felt that his cry for assistance should be heeded. From that initial gathering, the first of the Crusades began to drive out the Muslim invaders and save the Holy Land.

Although numerous historians have labeled the Crusades as nothing more then a self-serving expedition to rob, plunder, and loot, author Rodney Stark, a professor at Baylor University, has a different opinion. He believes that the Crusades were in fact a noble venture and were “not unprovoked,” nor were the Crusades the “first round of European colonialism.” His careful research has convinced him that the knights who participated in the Crusades sincerely believed that they were performing God’s duty and saving Christianity for the world.

On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery by Robert M. Poole, Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2009, 369 pp., index, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery by Robert M. Poole, Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2009, 369 pp., index, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

Historian Robert M. Poole has penned a moving narrative dealing with the origins, history, and daily operations of Arlington National Cemetery. Located on nearly 700 acres in Arlington, Virginia, the thousands of rows of white granite headstones are certainly awe-inspiring and poignant. For the majority of those buried there gave their lives in the defense of our country.

From the first person interred there, Union Army Private William Henry Christman of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry, to the remains of those returning from the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, the national landmark never ceases to stir emotions in the four million people who visit it annually.

From its humble beginnings, the cemetery has become the final resting place of many American veterans. Individuals such as Audie Murphy, Ira Hayes, and actor Lee Marvin, seriously wounded while serving as a Marine in World War II during the invasion of Saipan, are among the honored dead. Arlington serves as a constant reminder that the price of freedom is often paid in blood.

The Immortals: History’s Fighting Elites by Nigel Cawthorne, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 224 pp., index, glossary, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

The Immortals: History’s Fighting Elites by Nigel Cawthorne, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 224 pp., index, glossary, photos, $30.00, hardcover.

Military history is full of elite forces whose actions on the battlefield are legendary. From the 300 Spartans who sacrificed themselves at Thermopylae to the Special Forces units operating in Iraq and Afghanistan today, their incredible story continues to be written.

Cawthorne’s coffee table book features a synopsis of each elite unit, accompanied by illustrative paintings and photographs. Each group is listed in chronological order, beginning with the Persian Immortals who defeated the small band of Spartans at Thermopylae. Of particular interest are the battles of the Prussian Guard created by Frederick the Great. Although outnumbered, they fought fiercely in every campaign, with several members earning the Blue Max, Prussia’s highest military decoration.

The battles and campaigns of each specialized unit are an inspiration to future soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines. The modern servicemen who man such elite units are following a proud warrior tradition that their predecessors began many years ago. As the motto of the British-trained Gurkhas states, “Better to die than be a coward.”

Sea Service Medals: Military Awards and Decorations of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard by Fred L. Borch and Charles P. McDowell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 180 pp., notes, index, photographs, $34.95, hardcover.

Sea Service Medals: Military Awards and Decorations of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard by Fred L. Borch and Charles P. McDowell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 180 pp., notes, index, photographs, $34.95, hardcover.

Here is a book for readers wanting to learn more about the awards and decorations presented to Naval and Marine Corps personnel since their inception. The authors are experts in this field, and it is certainly evident in their interesting account.

Surprisingly, the Silver Star, the third-highest award for bravery under fire, was “not a popular award,” the authors note, because many felt that it was “insignificant in size and constitutes very little tangible evidence of gallantry, is not an article that can be handed down to posterity and, therefore, serve as an evidence of a grateful nation and people with attendant stimulation to patriotism.” A fascinating fact about the award is that its first recipient was Douglas MacArthur in World War I.

Each award, beginning with the Medal of Honor, is meticulously detailed. The writers discuss each medal’s historical background, who designed it and, in most cases, who was the first recipient. The criteria an individual must meet to be presented the decoration are discussed at length as well

Scottish Arms and Armour by Fergus Cannan, Shire Publications, Oxford, England, 2009, 120 pp., index, illustrations, photos, $19.95, softcover.

Scottish Arms and Armour by Fergus Cannan, Shire Publications, Oxford, England, 2009, 120 pp., index, illustrations, photos, $19.95, softcover.

Historian Fergus Cannan is not only an expert on the subject of Scottish weapons and other military subjects, he is a descendant of Highland warriors who more than likely used many of the weapons described in his new book. His account traces Scottish arms from their humble beginnings in 2200 bc, with axe heads made from stone, to the early 20th century, when ceremonial swords and knives were still worn by Scottish regiments.

Perhaps the best-known of these weapons is the Highland two-handed sword. Popular during the medieval period, it was one of the few swords that could stop an armor-clad knight. Another popular item was the sgian dhu, a small dagger that is still tucked into the sock of every Scot when he is dressed in formal attire. Another item that every Scot carried in battle was the sturdy leather shield, called a targe, that helped ward off the arrows of deadly British longbowmen.

Often described by the Scots as the “tools of freedom,” these weapons helped forge a nation. In battles such as Bannockburn, Flodden, and Stirling Bridge, heroic Scots fought for their freedom using the very weapons that Cannan describes in his book.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments