By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.d., U.S. Army (Ret.)

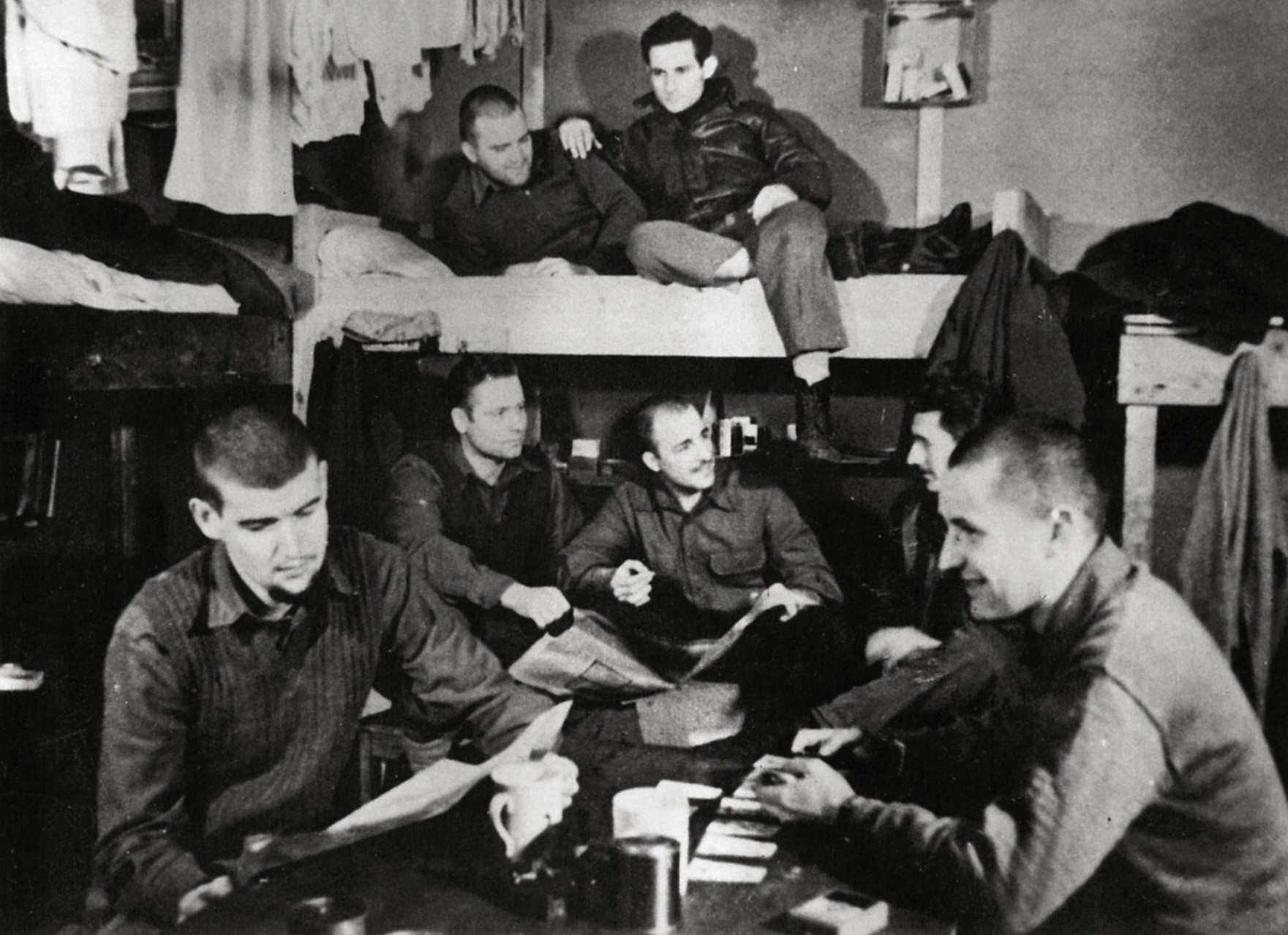

As a boy growing up in New York City in the 1950s, basketball great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then Lew Alcindor) idolized his father’s co-worker, Leonard “Smitty” Smith, and considered him a surrogate father. The senior Alcindor and Smitty both achieved responsible positions in the predominantly white New York City Transit Authority Police, but it was not until decades later that Abdul-Jabbar learned of Smitty’s pioneering and heroic role in World War II.

In 1992, after watching a documentary film on the black 761st Tank Battalion, Abdul-Jabbar learned for the first time that Smitty had been a decorated tank gunner in the 761st during World War II. This motivated Abdul-Jabbar, who was advocating greater recognition for black veterans, to write the excellent Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion, WWII’s Forgotten Heroes (Broadway Books, New York, 2004, 302 pp., illustrations, endnotes, select bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover). He then began collecting research materials and conducting interviews with 761st Tank Battalion veterans and was later assisted by Anthony Walton.

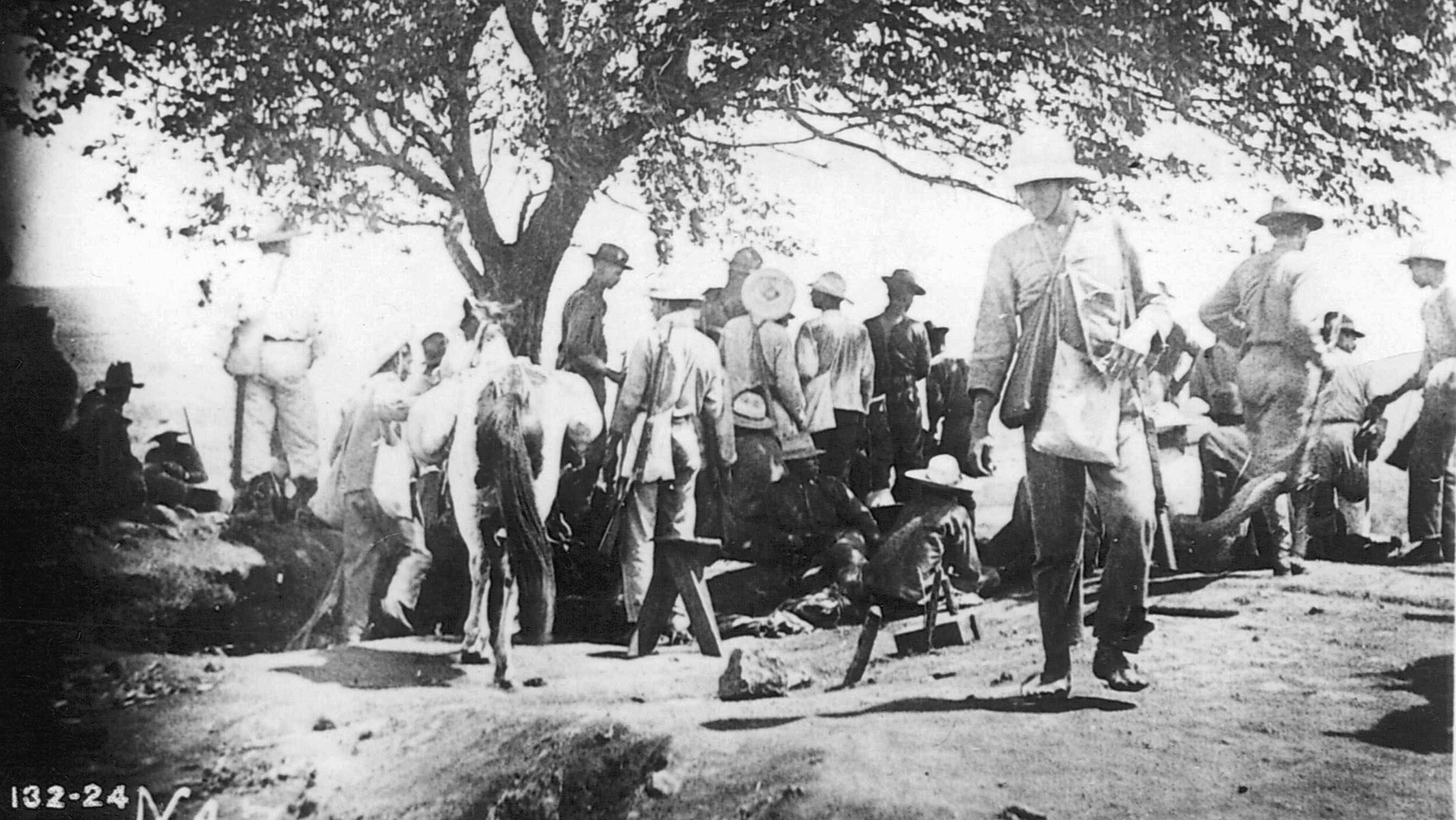

In the fall of 1942, the 761st Tank Battalion (African-American) was formed at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. This unit, along with the black 758th and 784th tank battalions and 99th Fighter Pursuit Squadron (the “Tuskegee Airmen”) had been organized, according to the authors, “not to fight but rather to placate black voters and the Negro press … as a way of solidifying Democratic party gains in the black community.”

This interesting book focuses on the activities, attitudes, and performance of three soldiers of the 761st: Leonard “Smitty” Smith, William McBurney, and Preston McNeil. Their early lives and aspirations, as well as the reasons they joined the army, helped provide a contextual background to this rare example of the black military experience in World War II.

Rome was captured on June 4, 1944, and the Normandy landings took place two days later. During the Normandy campaign, “American forces experienced unexpected difficulties and devastating casualties—particularly among the M-4 Sherman tanks and their crews, which were being lost by the hundreds.” The 761st was the best-trained and equipped tank battalion in the U.S. On June 9, 1944, to the welcome surprise of its soldiers, the battalion received orders to deploy to Europe.

Rome was captured on June 4, 1944, and the Normandy landings took place two days later. During the Normandy campaign, “American forces experienced unexpected difficulties and devastating casualties—particularly among the M-4 Sherman tanks and their crews, which were being lost by the hundreds.” The 761st was the best-trained and equipped tank battalion in the U.S. On June 9, 1944, to the welcome surprise of its soldiers, the battalion received orders to deploy to Europe.

The 761st received its baptism of fire in France in October 1944. The black tankers, while considered second-class soldiers in their own army, put aside racial friction and gallantly fought with their white comrades against the common German foe. Frequently leading the operations of Patton’s Third Army, the “Black Panthers” of the 761st continued the attack across the plains of France, through the bitter Battle of the Bulge, and into Germany and Austria by the war’s end in May 1945.

Even though the 761st sustained a casualty rate close to 50 percent and lost 71 tanks in 183 days of combat, its accomplishments were significant and its soldiers’ heroism was distinguished. The Black Panthers received 11 Silver Stars, 70 Bronze Stars, and over 250 Purple Hearts, in addition to a belated Medal of Honor and Presidential Unit Citation.

The authors skillfully use the experiences of Smith, McBurney, and McNeil to guide the reader through the peacetime struggles and combat tribulations of the brave black soldiers of the 761st Tank Battalion. Their poignant story, of soldiers overcoming racial prejudice on the battlefield and uniting to fight a common adversary, is inspiring and a delight to read.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Parade of the Dead: A U.S. Army Physician’s Memoir of Imprisonment by the Japanese, 1942-1945, by John R. Bumgarner, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, reprint, 2003, 212 pp., illustrations, appendix, map, $19.95, softcover.

“That morning, like every morning,” recalled U.S. Army Captain John R. Bumgarner, M.D., “I left my bahay [quarters] early to witness the parade of the dead, the burial procession of American prisoners of war who had died in the camp during the previous 24 hours.” This was the ghastly ritual of Bumgarner, an Army Reserve physician serving in the Philippines, after becoming a prisoner of war (POW) of the Japanese in April 1942. Transported to Cabanatuan, Bumgarner worked in the camp hospital, which only served “to segregate the very ill from the less ill.” Starved, filthy, tortured, and grossly maltreated, thousands of POWs died, and Bumgarner admitted feeling “less like a doctor than a caretaker of the dying.”

Bumgarner was transported with other POWs in early 1944 to Japan on the hellship Enoura Maru, the last ship carrying POWs to Japan that was not sunk. He spent the rest of the war in two camps in Japan, and after repatriation, he spent almost four years in hospitals being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Bumgarner’s medical expertise and keen observations in this riveting yet repulsive narrative provide an additional dimension to the unparalleled horror and unprecedented savagery of the Japanese during World War II.

In Brief

In Brief

No End Save Victory: Perspectives on World War II, edited by Robert Cowley, Berkley Books, New York, 2002, 688 pp., maps, $16.95, softcover.

This interesting collection of World War II essays has been culled from the pages of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. The 46 articles in this anthology, most written by prominent military historians on thought-provoking topics, are divided into six sections: “The German Breakout: 1939-1941”; “The Great East Asian War”; “World at War: 1942-1943”; “The Secret War”; “The End in Europe: 1944-1945”; and “Armageddon in the Pacific: 1944-1945.” While all essays are of a uniform high quality, a few merit individual recognition. Colonel Robert A. Doughty, in “Almost a Miracle,” explores the German breakthrough at the Meuse River in France in 1940, showing it to have been more precarious than generally considered. In “The Other Pearl Harbor,” D. Clayton James explores the lack of communications, indecisiveness, and ineptitude that resulted in the destruction of the U.S. Far East Air Force in the Philippines by the Japanese—after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Other authors include Bruce I. Gudmundsson, David M. Glantz, Joseph H. Alexander, Sir David Fraser, and Carlo D’Este. With riveting chapters that can be read in a single sitting, No End Save Victory warrants a large audience.

Volkswagen Military Vehicles of the Third Reich: An Illustrated History, by Blaine Taylor, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004, 187 pp., chronology, illustrations, tables, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover.

Volkswagen Military Vehicles of the Third Reich: An Illustrated History, by Blaine Taylor, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004, 187 pp., chronology, illustrations, tables, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover.

The Volkswagen, the “People’s Car,” was developed by Ferdinand Porsche with Adolf Hitler’s enthusiastic support in the 1930s purportedly as a symbol of the prosperity of the German Third Reich. This thoroughly researched book is mainly a pictorial history of the origin, design, and production of the Volkswagen (VW), as well as its post-war renaissance.

The VW was modified for military use during World War II. The VW Kubelwagen (“bucket car”) was a lightweight vehicle used extensively in North Africa and Russia, the Wehrmacht’s wartime equivalent of the U.S. Army’s jeep. Another VW derivative was the Schwimmwagen (“swimming car”), a four-wheel drive amphibious vehicle used in embattled Russia and Normandy. Clearly the highlight of this volume is its many VW illustrations, cut-away views, blueprints, and combat photographs. Hitler’s personal involvement in these VW development programs is interestingly depicted in many photographs. Author Blaine Taylor’s superb study is an invaluable reference work for wargamers, reenactors, and other military enthusiasts.

The Messman Chronicles: African Americans in the U.S. Navy, 1932-1943, by Richard E. Miller, Naval Intitute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 416 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Messman Chronicles: African Americans in the U.S. Navy, 1932-1943, by Richard E. Miller, Naval Intitute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 416 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

In the racially segregated 1930s and early World War II U.S. Navy, black sailors were generally relegated to mess attendant, officers’ cook, and steward positions. They, along with sailors of Filipino, Guamanian, and Chinese ethnicity, were “second-class” members of the sea service, the “messmen.” Despite this institutional prejudice, many black sailors—notably Mess Attendant Doris Miller, who manned his ship’s machine guns during the Pearl Harbor attack and received the Navy Cross for his heroism—willingly shed their blood defending their nation at war.

Author Richard E. Miller, a retired U.S. Navy chief hospital corpsman, conducted in-depth research and over 40 interviews with World War II-era minority Navy messmen while researching this volume. This superb book opens a window on the seldom seem trials and tribulations, and gallantry and contributions, of African American and other minority sailors during the period 1932-1943.

Last Man Out: Glenn McDole, USMC, Survivor of the Palawan Massacre in World War II, by Bob Wilbanks, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 179 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $29.95, softcover.

Last Man Out: Glenn McDole, USMC, Survivor of the Palawan Massacre in World War II, by Bob Wilbanks, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 179 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $29.95, softcover.

The “Palawan Massacre,” while overshadowed by larger atrocities during World War II, was another stunning example of Japanese barbarity and brutality in the Pacific. This story centers on Glen McDole, a 19-year-old Iowan when he joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1940. He was assigned to the Philippines and fought on Corregidor until it was surrendered to the Japanese on May 6, 1942.

McDole was one of about 300 men sent to the Japanese prisoner-of-war (POW) camp on Palawan Island. Through mesmerizing yet frequently hideous detail, the reader witnesses the Japanese beatings, executions, and McDole’s perseverance, “living in conditions no Iowa farmer would impose on his cattle or hogs.” On December 14, 1944, believing American forces were nearby, the Japanese conducted a mock air raid drill for the POWs. The Japanese used this as an excuse to massacre the POWs “burning, shooting, bayoneting, and murdering” 139 of the remaining prisoners. McDole was one of 11 men who escaped the slaughter and returned to the U.S. to report the atrocity. This excellent book reveals the depths of Japanese inhumanity and McDole’s steadfast courage in surmounting mind-numbing adversity.

Spies for Nimitz: Joint Military Intelligence in the Pacific War, by Jeffrey M. Moore, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, maps, tables, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Spies for Nimitz: Joint Military Intelligence in the Pacific War, by Jeffrey M. Moore, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, maps, tables, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area (JICPOA) was, according to Jeffrey M. Moore, “the United States’ first effective, all-source intelligence unit.” Operating from September 7, 1943, until the end of World War II, the unit mainly supported Admiral Chester Nimitz, Pacific Fleet commander in chief, and his operations in the central, western, and southern Pacific.

JICPOA contained over a thousand intelligence specialists who performed various duties, including “analyzing Japanese radio traffic and studying photographs of enemy-held islands, to accompanying infantry forces on beach assaults to process vital combat intelligence.”

Moore chronicles the evolving effectiveness of military intelligence and its impact on the Pacific war through a series of case studies. These examples include amphibious operations in the Marshall Islands, the Marianas, Peleliu, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands. Moore concludes in this thoughtful study, “JICPOA’s strategic intelligence had a tremendous influence on Nimitz and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.” Soundly researched and well written, this excellent book makes a major contribution to the evolution and application of military intelligence in wartime.

Lost in Tibet: The Untold Story of Five American Airmen, a Doomed Plane, and the Will to Survive, by Richard Starks and Miriam Murcutt, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2004, 210 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, $22.95, hardcover.

Lost in Tibet: The Untold Story of Five American Airmen, a Doomed Plane, and the Will to Survive, by Richard Starks and Miriam Murcutt, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2004, 210 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, $22.95, hardcover.

Flying “the Hump,” the aerial resupply route from India to China over the towering and treacherous Himalaya Mountains during World War II, was routinely a dangerous mission. In November 1943, an American C-47 cargo plane with a crew of five took off from Kunming, China, bound for India.

As darkness fell, a violent storm blew the plane off course. Before running out of fuel, the crewmen parachuted and were astonished to find themselves in Tibet. They were escorted to Lhasa, where they were among the first Americans to enter the Forbidden City. Political intrigue and machinations resulted in the eventual repatriation of the American airmen. This is a gripping military adventure tale of a little-known episode of the Second World War.

The Path to Victory: The Mediterranean in World War II, by Douglas Porch, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2004, 799 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, selected bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

The Path to Victory: The Mediterranean in World War II, by Douglas Porch, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2004, 799 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, selected bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

In this sweeping narrative, based upon secondary sources and personal reflection, Naval Postgraduate School Professor Douglas Porch examines World War II military operations in the Mediterranean theater. Interestingly, Porch views the Mediterranean theater “as a geographic and strategic whole, rather than as a sequence of discrete campaigns.”

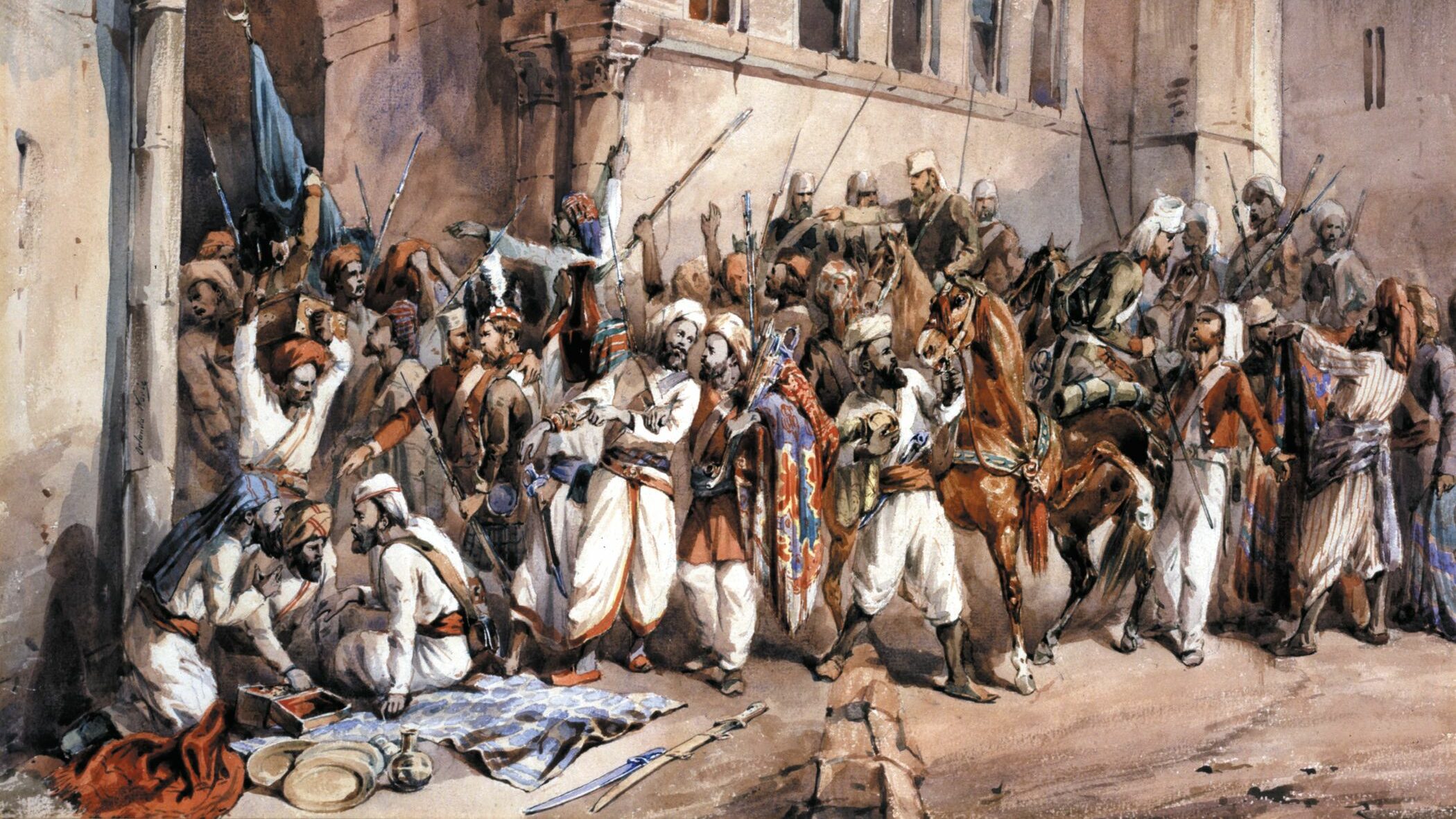

The many North African and Mediterranean campaigns—from Wavell’s 1940 Operation Compass in the Western Desert to the 1942 Torch landings and Battle of El Alamein, and the 1943 invasions of Sicily and Italy—are chronicled and assessed within the framework “of the interaction between air, sea, and land power in a multifaceted operational environment.” Porch also evaluates, insightfully and frequently critically, the generalship of senior commanders including Eisenhower, Alexander, Patton, Montgomery, and Clark.

Interesting photographs enhance the text, but the maps are difficult to read and there are misinterpretations of sources. The author argues convincingly that the “Mediterranean was the European war’s pivotal theater, the critical link without which it would have been impossible for the Western Alliance to go from Dunkirk to Overlord.” Porch’s elegantly written study makes a valuable addition to one’s World War II bookshelf.

Eisenhower and the Art of Warfare: A Critical Appraisal, by D.J. Haycock, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2004, 234 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover.

Eisenhower and the Art of Warfare: A Critical Appraisal, by D.J. Haycock, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2004, 234 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover.

The relative merits and effectiveness of the World War II generalship of General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower and British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery have been debated for decades. Author D.J. Haycock begins this volume by stating, “The more I read, the more convinced I became that too few authors had given an objective portrait of Eisenhower’s wartime accomplishments, and too few had credited Montgomery for his achievements.”

This sets the tone for the book. Haycock surveys the World War II North African and European military operations beginning with “The Decision to Invade North Africa” and ending with “The End of the War in Europe.” In each chapter, Haycock mainly highlights and assesses Eisenhower’s performance and decision-making abilities, occasionally out of context, generally without a thorough understanding of coalition warfare, and frequently without adequate supporting documentation.

Montgomery’s generalship is addressed secondarily. The evidence seems to have been selectively mustered to support Haycock’s contentious claim that “military history is unlikely to deal kindly with [Eisenhower] and all the panegyrics by those who, with so little justification, believe he was a near genius cannot alter the conclusion that Eisenhower failed as a military commander.”

D-Day + 60 Years: A Small Piece of History, by Jerome J. McLaughlin, Authorhouse, Bloomington, IN, 2004, 281 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, endnotes, bibliography, $19.45, softcover.

D-Day + 60 Years: A Small Piece of History, by Jerome J. McLaughlin, Authorhouse, Bloomington, IN, 2004, 281 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, endnotes, bibliography, $19.45, softcover.

The genesis of this book was Jerome J. McLaughlin’s search for the circumstances surrounding the death of his uncle, 1st Lieutenant Joseph Sullivan, during World War II. McLaughlin’s quest revealed that his uncle was a navigator in a Douglas C-47 of the 435th Troop Carrier Group. Sullivan’s plane was shot down over France early on D-Day while transporting paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division in the invasion of Europe. McLaughlin compiled accounts of D-Day, and later reunion recollections, from his uncle’s wartime comrades and French civilians he later met, and cobbled them into a mosaic that sheds light on Sullivan’s military exploits. This is an intriguing and heartwarming story of military comradeship and family loyalty undimmed through the decades since World War II.

Terrible Terry Allen: Combat General of World War II – The Life of an American Soldier, by Gerald Astor, Presidio, New York, 2003, 374 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Terrible Terry Allen: Combat General of World War II – The Life of an American Soldier, by Gerald Astor, Presidio, New York, 2003, 374 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Army Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen was the hard-fighting, hard-swearing, unorthodox commander of two infantry divisions during World War II. He led the 1st Infantry Division, the “Big Red One,” in the landings in North Africa and Sicily and in subsequent fierce combat operations. While many people praised his leadership and his soldiers seemingly idolized him, others were concerned that the care he gave his soldiers caused ill discipline and misbehavior.

While this resulted in Allen’s relief in 1943, he was later given command of the fledgling 104th Division. He led the 104th Division, the “Timberwolves,” in combat in Europe from October 1944, through its link-up with Soviet forces at the Elbe River in April 1945, until its inactivation at the end of 1945. Allen retired from the army in 1946 and died in 1969, two years after his son was killed in action in Vietnam. This biography of Allen, written remarkably without a single note, is very interesting but leaves a number of questions about his military performance and career unanswered. Future biographers of Allen and military readers will find this chronicle of considerable value.

The Americans at D-Day: The American Experience at the Normandy Invasion, by John C. McManus, Forge, New York, 2004, 400 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, select bibliography, index, $26.95, hardcover.

The Americans at D-Day: The American Experience at the Normandy Invasion, by John C. McManus, Forge, New York, 2004, 400 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, select bibliography, index, $26.95, hardcover.

“From the earliest I can remember,” observed author John C. McManus, “I have been fascinated with Operation Overlord and the Battle of Normandy.” While others of post-World War II generations share these sentiments, those World War II soldiers, and especially those who landed at Normandy on D-Day, recognize the operation as having been decisive and representative of the excellent American effort in the war.

McManus has written for a general audience a gripping chronicle of the preparations for and conduct of the unprecedented airborne and amphibious assaults on D-Day. Using many recently collected oral histories recorded decades after the event, the strategic decisions of generals to the heroic actions of infantrymen at the tip of the spear fighting the enemy are narrated in detail. This superbly written and fast-paced book, highlighting the human dimension of warfare, is a fitting tribute to those stalwart soldiers who stared death in the face six decades ago at Normandy.

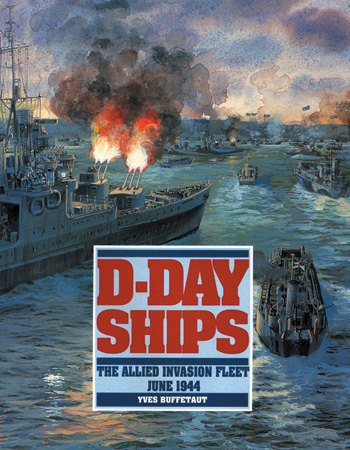

D-Day Ships: The Allied Invasion Fleet, June 1944, by Yves Buffetaut, Conway Maritime Press, London, reprint, 2004, 162 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, further reading, index of ships’ names, $49.95, hardcover.

D-Day Ships: The Allied Invasion Fleet, June 1944, by Yves Buffetaut, Conway Maritime Press, London, reprint, 2004, 162 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, further reading, index of ships’ names, $49.95, hardcover.

The Normandy landings on D-Day, June 6, 1944, constitute the largest amphibious undertaking in history. The experience gained from landings at Gallipoli in World War I and at Dieppe, France, in North Africa, on Sicily, and elsewhere provided valuable lessons for the Allies. In this profusely illustrated volume, historian Yves Buffetaut emphasizes the naval role in all phases of the planning, support, execution, and consolidation of Operation “Overlord.”

Detailed descriptions and plans of the many types of landing craft and ships are provided, and the major Allied naval units and warships are depicted in similar detail. Two of the most interesting chapters focus on “The Artificial Ports,” the Mulberries and the Gooseberries, and “The Storm” of June 19-22, 1944, that battered many ships and severely disrupted Allied resupply operations. The crossing of the English Channel and support of the Allied landings involved some 1,213 warships out of a mind-numbing total of 5,333 naval vessels and craft of all types. This fascinating book chronicles in rich detail and with superb illustrations the indispensable naval contribution to the 1944 Normandy landings.

Hellcats: The 12th Armored Division in World War II, by John C. Ferguson, State House Press, Abilene, TX, 2004, 160 pp., chronology, illustrations, appendices, endnotes, bibliography, index, $16.95, softcover.

Hellcats: The 12th Armored Division in World War II, by John C. Ferguson, State House Press, Abilene, TX, 2004, 160 pp., chronology, illustrations, appendices, endnotes, bibliography, index, $16.95, softcover.

The 12th Armored Division – the “Hellcats” – was one of 16 armored divisions of the 89-division strong U.S. Army in World War II. Activated at Camp (later Fort) Campbell, Kentucky, in September 1942, the 12th Armored Division (12th AD) was organized and trained in Texas and at other locations before deploying to France in November 1944. It began combat operations the following month and fought during the fierce Battle of the Bulge.

The 12th AD attacked German forces in Herrlisheim at least three times in January 1945, with each assault failing miserably and causing the virtual annihilation of two battalions. After this bloody fighting, the Germans dubbed the 12th AD the “Suicide Division.” The 12th AD continued to drive east, helped shatter the Colmar Pocket, crossed the Rhine River, and helped liberate Nazi concentration camps at Hurlag, Landsberg, and Dachau. The experienced and feared 12th AD ended the war in Austria. This well written monograph contains many superb illustrations and maps and a detailed chronology. Even though the 12th Armored Division was inactivated in December 1945, the heritage and fighting spirit of the stalwart Hellcats lives on in this excellent unit history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments