By Al Hemingway

Although the bloody Sepoy insurrection of 1857 was SPARK- ed by the introduction of the new Enfield rifle, the seeds of mistrust between Indian soldiers and their British colonial masters were planted long before that. The growing fear that the British wanted to convert the Sepoys (native soldiers) to Christianiity and do away with their Hindu and Muslim faiths was an ever-present threat in the popular mind. The encroaching territorial gains of the East India Company and its total disregard for native culture and traditions also frightened and angered the Indians.

When the new 1853 Enfield percussion cap rifle was issued, the cartridge had to be bitten open and the gunpowder poured down the muzzle. Then the casing was rammed into the barrel to act as wadding. A rumor spread that the cartridges were lubricated with pig fat and beef tallow—materials that were strictly forbidden to be eaten by Hindus or Muslims. The rumor was false, but when the British high command proved intransigent on the issue, thousands of Sepoys launched a rebellion that would become one of the bloodiest in British military history.

When the new 1853 Enfield percussion cap rifle was issued, the cartridge had to be bitten open and the gunpowder poured down the muzzle. Then the casing was rammed into the barrel to act as wadding. A rumor spread that the cartridges were lubricated with pig fat and beef tallow—materials that were strictly forbidden to be eaten by Hindus or Muslims. The rumor was false, but when the British high command proved intransigent on the issue, thousands of Sepoys launched a rebellion that would become one of the bloodiest in British military history.

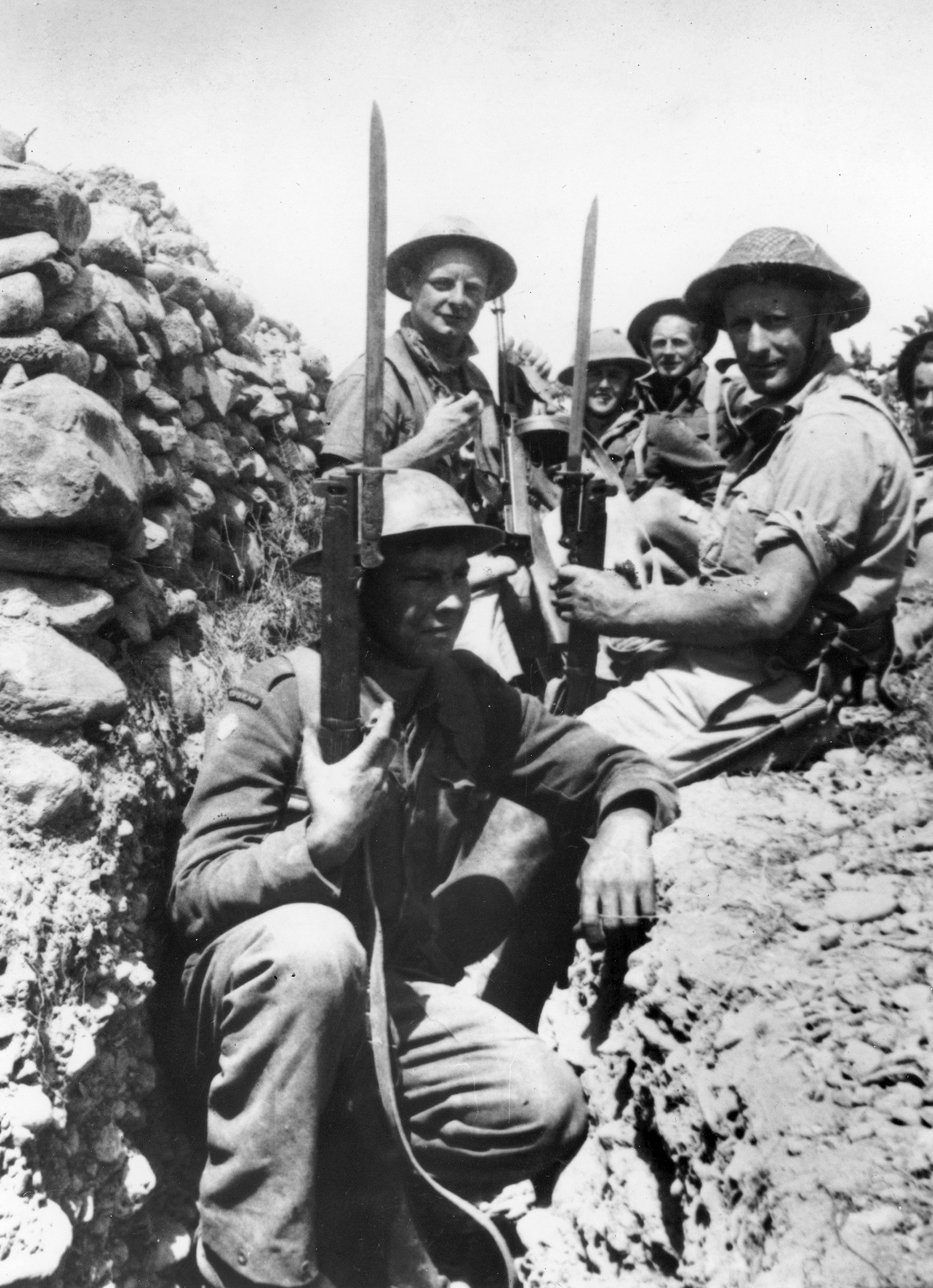

In The Defence of Lucknow: T.F. Wilson’s Memoir of the Indian Mutiny, 1857 with an introduction by noted historian Saul David (MBI Publishing Company, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 172 pp., photographs, maps, $29.95, hardcover), Captain Thomas F. Wilson, a staff officer serving with Chief Commissioner Sir Henry Lawrence, penned a riveting day-by-day account of the horrors faced by the British and their allies during the siege at Lucknow. With a force of about 1,700 men that included British soldiers, loyal Sepoys, and civilians, Lawrence established defensive positions in an area called the Residency. For the next 87 days, the British held out, their supplies and their hope dwindling steadily.

Wilson gives the reader a dramatic rendering of the horrific conditions the inhabitants had to endure. On July 7, Wilson wrote, “Major Francis, 13th Native Infantry was struck in the legs by a round shot rendering amputation of one immediate, and great fears were entertained for the other. The calm manner in which he bore his misfortune, gained him the sympathies of all.” The officer died the following day.

Wilson was also present when Lawrence was mortally wounded. He recounts, “Soon after an eight-inch shell from the eight-inch howitzer of the enemy, entered the room at the window, and exploding, a fragment struck the Brigadier-General on the upper part of the right thigh near the hip, inflicting a fearful wound.” Standing by the bed where Lawrence was resting, Wilson narrowly escaped death when the explosion caused part of the building to collapse. The falling bricks knocked him to ground and a small piece of shrapnel lodged in his back. Sir Lawrence passed away several days later from his wound.

Many civilians, including women and children, were killed during the fighting at Lucknow. Diseases such a smallpox and cholera also claimed numerous lives. The putrid odor of decaying animal carcasses, Wilson notes, filled the humid air, making the “stench from the dead animals in some parts dreadful.”

A relief force finally reached Lucknow on September 25, and the occupants of the besieged city celebrated. Wilson noted the great event: “The garrison’s long pent-up feelings of anxiety and suspense burst forth in a succession of deafening cheers. From every pit, trench and battery—from behind the sandbags piled on shattered houses—from every post still held by a few gallant spirits, rose cheer on cheer—even from the hospital! It was a moment never to be forgotten.”

Wilson’s journal is rich with detail of the horrible conditions the residents of Lucknow were forced to suffer for nearly three months. As Saul David states in his introduction, Wilson’s account is “among the finest war diaries ever written.” The book adroitly captures the fighting spirit of the British and native soldiers who endured much in their despairing defense of Lucknow.

Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War by Tom Wheeler, HarperCollins Books, New York, New York, 2006, 227 pp., index, $24.95, hardcover.

Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War by Tom Wheeler, HarperCollins Books, New York, New York, 2006, 227 pp., index, $24.95, hardcover.

In 1857, Abraham Lincoln was representing legal clients in Pekin, Illinois, when he acquired a room at the Tazewell House in town. A telegraph office had been established in the hotel, and Lincoln watched with great interest as Charles Tinker, the operator, tapped out messages. Mesmerized by the new technology, the future president quizzed Tinker on the theory behind its operation. With his agile mind, Lincoln quickly grasped how the new invention worked and immediately realized its future importance.

Although the Confederate Army also used the telegraph during the Civil War, it was Lincoln who used it most effectively. By the start of the war, he had already had much favorable exposure to the technology. Telegraphed accounts of his famous debates with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas in the 1858 Senate race had catapulted Lincoln into the national spotlight. The telegraph had also brought news of his victory in the 1860 presidential election, an event that soon would spark the Civil War. And it would be the telegraph, through Lincoln’s unique style of leadership and communication skills, that would eventually help to win the conflict.

At the outset of the war, Lincoln used the telegraph sparingly. It wasn’t until the spring of 1862 when Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson began his brilliant Shenandoah Valley campaign that Lincoln began to rely on the telegraph to bring him important news from the battlefield. With Washington, D.C., threatened on two fronts, Lincoln kept in constant communication with his generals in the field and “began to assert his authority directly to the field,” author Tom Wheeler notes, referring to this as an “electronic breakout.” From that point on, Lincoln spent countless hours in the telegraph office reading not only his own telegrams, but messages not addressed to him as well. This enabled him to attain valuable information and learn a great deal more about the men leading the troops.

Wheeler traces Lincoln’s use of the telegraph through his years in the White House. In all, the president issued an astonishing 1,000 telegrams during the Civil War. Up to that time, no other president had such technology at his fingertips, and Lincoln had no frame of reference. He only had his own intuition to guide him. As his confidence with the new instrument grew, so did his leadership abilities. As Wheeler writes, “Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails are a chronicle of how one man, even while confronted by a civil war, applied new technology to define a new kind of electronic leadership.”

Greene: Revolutionary General by Steven E. Siry, Potomac Books, Washington, DC, 2006, 116 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $13.95, softcover.

Greene: Revolutionary General by Steven E. Siry, Potomac Books, Washington, DC, 2006, 116 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $13.95, softcover.

One of the ablest American officers to emerge from the Revolutionary War was Nathaniel Greene. A native of Rhode Island, Greene was raised by strict Quaker parents. His early life showed no indications of a military career. Instead, Greene entered his father’s shipping business. When the British government started imposing harsh taxation and laws against personal liberties on the American colonists, Greene became infuriated. He readily embraced the revolutionary movement and enlisted as a private in the Rhode Island militia.

Greene had a swift rise to brigadier general and was soon a part of George Washington’s inner circle. He performed admirably during the New York and New Jersey campaigns, but he really shone when he was promoted to major general and went south to keep the British at bay in North and South Carolina. His innovative use of guerrilla warfare and fast-moving tactics kept the enemy off balance and contributed greatly to the eventual American victory at Yorktown. Greene was the only general to serve on Washington’s staff faithfully for the entire duration of the war. He died of sunstroke in 1786, five weeks before his 44th birthday. Greene’s fierce determination was aptly summed up in his own words: “We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again!”

History’s Great Untold Stories: The Larger Than Life Characters & Dramatic Events That Changed the World by Joseph Cummins, National Geographic, Washington, DC, 2006, 367 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

History’s Great Untold Stories: The Larger Than Life Characters & Dramatic Events That Changed the World by Joseph Cummins, National Geographic, Washington, DC, 2006, 367 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Author Joseph Cummins has done a remarkable job of compiling 28 of the most fascinating historical events and people who left an indelible mark on world history, whether for good or bad. There is just one problem—most of these figures and events have rarely, if ever, been heard of before.

One good example is the tale of the “Leper King.” In the latter part of the12th century, the Islamic ruler Saladin threatened to destroy the Crusader States, a territory that included Jerusalem, Tripoli, and Beirut. Inhabited by descendants of the Crusaders, many were Catholics who practiced their religion openly. Faced with a Muslim invasion, people naturally looked to their ruler for help. Baldwin IV was a 16-year-old who “was afflicted with a disease which caused his face to ooze with raw ulcers, turned his hands and feet into little more than suppurating paws, and struck him blind,” writes Cummins. The king suffered from leprosy. This dreaded affliction would have prompted any other person to be confined to a leper colony. But to the inhabitants of the Crusader States, he was a magnificent ruler.

Baldwin led his men in combat and defeated Saladin’s forces at the Battle of Mont Gisard in November 1177. In July 1182, he once again routed the enemy at the Battle of Le Forbelet, even though he was vastly outnumbered. The Leper King died in 1184 at the tender age of 23. Without his leadership, the kingdom of Jerusalem would soon collapse. Cummins’s book is full of such captivating stories of little-known individuals who had a tremendous impact on world history.

Sub: An Oral History of U.S. Navy Submarines by Mark Roberts, Berkley Publishing Co., New York, 2007, 298 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Sub: An Oral History of U.S. Navy Submarines by Mark Roberts, Berkley Publishing Co., New York, 2007, 298 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

From its inception, the submarine has fascinated the American public. Historian Mark Roberts has collected 13 oral histories of men who served on various submarines during war and peace. Their stories about life aboard the cramped vessels will definitely hold your interest.

Lieutenant Commander Chris Kreiss, USN (Ret.) tells about his exploits aboard the USS Batfish during World War II in the Philippines. “Another sub appeared, also headed south,” he notes. “This one dove just about the time we closed her and was about ready to fire. Only suddenly, she came back up on the same bearing. We wanted to make an approach on her. We lost some time because we had to swing around and fire torpedoes from our stern tubes. We’d run out of torpedoes up in the bow. We had to make our approach and then do a 180-degree turn in order to fire, which we did, and sunk that one, too. We had a regular feast of Japanese subs.”

Roberts’s account is a tribute to all those men who served, and are still serving, aboard submarines. Their dedication, bravery, and heroism have earned them the right to proudly wear the coveted dolphin—the emblem of a submariner.

The Yugoslav Wars (2): Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia 1992-2001 by Dr. N. Thomas & K. Mikulan, Osprey Publishing, 2006, 64 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $17.95, softcover.

The Yugoslav Wars (2): Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia 1992-2001 by Dr. N. Thomas & K. Mikulan, Osprey Publishing, 2006, 64 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $17.95, softcover.

The savage conflict that raged in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia for nearly a decade in the 1990s can be confusing for the average American to understand. Ethnic hatreds and religious persecutions fostered years of bloodshed in which thousands of innocent people perished. It left an ugly mark on Eastern Europe that caused worldwide condemnation. Eventually, a multinational force intervened to put a stop to the slaughter.

The authors’ book is not a history of that conflict. Instead, it provides readers with a detailed look at the various uniforms, patches, and military insignia worn by the many factions involved in the fighting. As with other Osprey publications in this series, it is full of meticulous artwork, rare photographs, charts, and tables explaining the rank structure and garb worn by the military and paramilitary groups.

For those who collect the books in this Elite series, put this one at the top of your list. You will not be disappointed.

Charge! Great Cavalry Charges of the Napoleonic Wars by Digby Smith, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 304 pp., illustrations, maps, $24.95, softcover.

Charge! Great Cavalry Charges of the Napoleonic Wars by Digby Smith, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 304 pp., illustrations, maps, $24.95, softcover.

Meerheim, an officer riding with the Saxon Garde du Corps who participated in the Battle of Borodino, wrote, “We charged at the ravine and ditch, the horses clearing the bristling fences of bayonets. The combat was frightful! Men and horses hit by gunshots collapsed into the ditches and thrashed around among the dead and dying, each trying to kill the enemy with their weapons, their bare hands or even their teeth.”

Throughout military history, the sound of bugles accompanying a cavalry charge has had an air of romanticism surrounding it. Gallantly uniformed Lancers and Hussars waving their swords above their heads atop horses in full gallop have captured the imagination of many a history buff. As Meerheim describes during the fight at Borodino, where the Raevski Battery was overrun, there was little actual glory in the brutal hand-to-hand struggle when two armies clashed.

Charge! explains the different types of cavalry, the tactics they employed, and the care of the horses during various battles of the Napoleonic era. Cavalry charges did not begin at a full gallop but rather a walk, then a trot. It wasn’t until the cavalry had closed to within 50 paces was the command of charge finally given.

Author Digby Smith has included comprehensive charts at the end of the book listing the many cavalry units employed by both sides in the battles he examines meticulously in his book.

Rome’s Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to the Alaric by Michael Kulikowski, Cambridge University Press, 2007, 225 pp., maps, glossary, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Rome’s Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to the Alaric by Michael Kulikowski, Cambridge University Press, 2007, 225 pp., maps, glossary, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

In the summer of ad 410, the once great Roman Empire was in a shambles. Many of its citizens were starving while a Gothic army, under the command of Alaric, had positioned itself just outside the city. A sense of unparalleled foreboding hung in the air.

Against this backdrop, the author has written an engrossing account of Alaric and the rise of his Goths within the Roman military structure. Born in 370 on the small island of Peuce at the mouth of the Danube, Alaric (who name means “Everyone’s king”) was leader of the Visigoths for 15 years. He was the first Germanic ruler to actually seize Rome. His troops ransacked the Eternal City for three days in 410, signaling unmistakably the decline of Rome’s power and prestige.

Ironically, it was the Romans themselves who created the Goths from “the pressures of life on the Roman frontier.” A gifted leader, Alaric would take them to greater and greater glory just before his untimely death from a fever in 410. But before his passing, Alaric had brought a new spirit of freedom for other barbarian tribes who would follow his example and make their own bloody marks on Roman history.

The Blog of War: Front-Line Dispatches from Soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan by Matthew Currier Burden, Simon & Schuster, New York, New York, 2006, 291 pp., glossary, index, $15.00, softcover.

The Blog of War: Front-Line Dispatches from Soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan by Matthew Currier Burden, Simon & Schuster, New York, New York, 2006, 291 pp., glossary, index, $15.00, softcover.

With computer access available to our military personnel fighting in the Middle East, many of the soldiers are giving personal and intense accounts of life in a war zone. With the blog, an online diary, these stories present an intimate glimpse into the world of the individual serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. MilBlogs, as they are called, have been used since the invasion of Afghanistan and have filled in details, both large and small, not included in military and media accounts of events transpiring in the war-torn countries.

The human cost of war comes home throughout the collection. “There was already a pool of blood under the man’s head, running down his arm, soaking his clothes,” wrote one medic. “I gagged, saliva pooling in my mouth. God I was going to be sick.”

Gut-wrenching blogs such as these help bring the war home to the carefully sheltered American public. The author established his own site, Blackfive.net, to support the men and women fighting the war on terror. The American government is now in the process of shutting down all of these blog sites and imposing censorship on the troops. If this happens, we will lose our most accurate and instantaneous methods of accruing accurate and timely information about the ongoing conflict in the Middle East.

Portrait of War: The U.S. Army’s First Combat Artists and the Doughboy’s Experience in WWI by Peter Krass, John Wiley & Sons, 2007, 342 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $30.00, hardcover.

Portrait of War: The U.S. Army’s First Combat Artists and the Doughboy’s Experience in WWI by Peter Krass, John Wiley & Sons, 2007, 342 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $30.00, hardcover.

Ever since Harper’s Weekly sent their illustrators into the field to cover the American Civil War, combat artists have become an essential part of the media coverage of American conflicts. It wasn’t until World War I, however, that the U.S. Army actively sought artists to go overseas and record the experiences of the common American soldier. Unlike the photojournalists of today’s military, embedded in specific units, the eight men covered in this book were given a free hand to venture anywhere to draw scenes that told the story of the everyday life of the soldier.

When author Peter Krass was given a present of a book of drawings from that period, it started him on a quest to learn more about these individuals. He was fortunate to meet the family of one such artist, George Harding, who allowed him access to his diary. This valuable find gave him a historical window into another era—a fascinating period of our nation’s history—from the close-hand viewpoint of the combat artist.

LeMay by Barrett Tillman, Palgrave MacMillan, 2006, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $21.95, hardcover.

LeMay by Barrett Tillman, Palgrave MacMillan, 2006, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $21.95, hardcover.

One of the most controversial leaders to emerge from World War II was certainly Curtis Emerson LeMay. LeMay’s fascinating career as a pilot and strategist is profiled in this series on influential American generals.

Born in 1906, LeMay was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1930 and entered the Army Air Corps. In World War II, he developed the “combat box formation” during his stint as air commander in Europe. Combative and charismatic, LeMay would personally lead dangerous missions deep into Nazi-controlled territory with no bomber escort. He was quickly promoted to major general and sent to the Pacific, where he oversaw the B-29 bombing raids over Japan that included the punitive firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945.

In his post World War II assignments, LeMay constantly clashed with his civilian superiors. His aggressiveness and hard-charging attitude prompted detractors to nickname him “Bombs Away LeMay.” Perhaps his most famous line was uttered at the beginning of the Vietnam War, when he said: “My solution to the problem would be to tell them frankly that they’ve got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression, or we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Age.”

Upon his retirement, LeMay dabbled in politics by becoming Alabama Governor George Wallace’s running mate in 1968, but that soon fizzled. On October 1, 1990, he died. His remains were interned at the United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs, Colorado, where subsequent generations of American pilots and bombers have trained.

Georg Von Trapp To the Last Salute: Memories of an Austrian U-Boat Commander, translated by Elizabeth M. Campbell, University of Nebraska Press, 2007, 192 pp., illustrations, maps, $21.95, hardcover.

Georg Von Trapp To the Last Salute: Memories of an Austrian U-Boat Commander, translated by Elizabeth M. Campbell, University of Nebraska Press, 2007, 192 pp., illustrations, maps, $21.95, hardcover.

Whenever the name Von Trapp is heard, most people conjure up thoughts of the treacly 1960s musical The Sound of Music, starring Julie Andrews with Christopher Plummer in the role of Georg Von Trapp, the stern father of a musical brood of Teutonic children. The film traces the family’s narrow escape from their Nazi pursuers without ever answering the question, Why did the German officials want him so badly? Coming from an aristocratic family, Von Trapp was a veteran of World War I, having commanded U-boats in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas. As a veteran of that conflict, especially in submarine warfare, Von Trapp was prized by the Nazis, who felt he could provide invaluable service to the Third Reich.

In his personal account, translated by his granddaughter Elizabeth Campbell, Von Trapp captures the feeling of a bygone era where chivalry and love of country were paramount. First published in 1935, this is the first English version of his biography.

His amazing exploits in the Great War and life-and-death experiences as a commander of various U-boats will enthrall readers.

American Patriot: The Life and Wars of Colonel Bud Day by Robert Coram, Little, Brown and Co., 2007, 416 pp., illustrations, index, $27.99, hardcover.

American Patriot: The Life and Wars of Colonel Bud Day by Robert Coram, Little, Brown and Co., 2007, 416 pp., illustrations, index, $27.99, hardcover.

An American hero is one way to describe Colonel George” Bud” Day, a veteran of three wars and POW in the infamous Hanoi Hilton for 67 months. His personal decorations, including the Medal of Honor, are too numerous to mention. It wasn’t until after his retirement, however, that Day would experience another type of combat, this time in a court of law.

As a practicing attorney in the State of Florida, Day sued the United States government in 1996 for breach of contract on behalf of World War II and Korean War veterans. The government had reneged on its promise to provide lifetime medical benefits to all those who served in these wars, he charged. In 2000, Day won a signal victory by restoring 95 percent of their benefits. “None of us WWII/Korea/Vietnam War vets want our service people to suffer,” wrote Day. “We are not at fault for a shortage of money to the military. It is the Congress who is shortchanging the military for the weapons and equipment they need for combat not the retired military veteran and his spouse.”

Wingmen: Two Friends, Four Wars, Flying and Fighting Through the 20th Century by Peter J. Wurts & William R. Yoakley, Wurts Publishing, Pacific Grove, CA, 2006, 324 pp., illustrations, $23.99, softcover.

Wingmen: Two Friends, Four Wars, Flying and Fighting Through the 20th Century by Peter J. Wurts & William R. Yoakley, Wurts Publishing, Pacific Grove, CA, 2006, 324 pp., illustrations, $23.99, softcover.

There are few greater friendships than those forged during time of war. The hardships people are forced to endure leave lasting impressions upon them and the comrades with whom they shared them. Peter J. Wurts and William Yoakley are two such friends. They first met in 1943 in California while undergoing training to be pilots in the Army Air Corps. This chance meeting would form a friendship that would last over 60 years through World War II, Korea, the Cold War, and Vietnam.

“Although our book is a labor of love,” wrote the authors, “we tackled it the way any pilot approaches a new plane: cautiously at first, then with increasing confidence but always with respect for the facts, for our readers and for the people whose lives we shared.” In turn, they have shared their lives and experiences with a new generation of readers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments