By Sam Mcgowan

On June 6, 1944, Allied troops landed in Normandy, commencing the offensive that liberated Western Europe and contributed to the final Allied victory in Europe. It was a tremendous effort that has caught the attention of historians and the media alike, but whether or not it was the most ambitious or dangerous effort of the war is debatable. For almost four years the Allies had been waging an aerial offensive against Germany that accounted for more casualties than any other campaign of the war.

Begun by the British Royal Air Force Bomber Command in 1940, the air war against Nazi Germany had been joined by bomber crews from the U.S. Eighth Air Force in the summer of 1942. Over the next two and a half years, the Eighth Air Force would lose more men than the entire U.S. Marine Corps and would suffer the most losses of any U.S. Army unit. Many died, but thousands of young airmen ended up in the hands of the Germans, who incarcerated them in prison camps for the duration of the war. One of those young airmen was T/Sgt. Ned Handy. He tells his story, with the assistance of Kemp Battle, in The Flame Keepers: The True Story of an American Soldier’s Survival Inside Stalag 17, Hyperion, New York, 2004, 336 pp., $24.95.

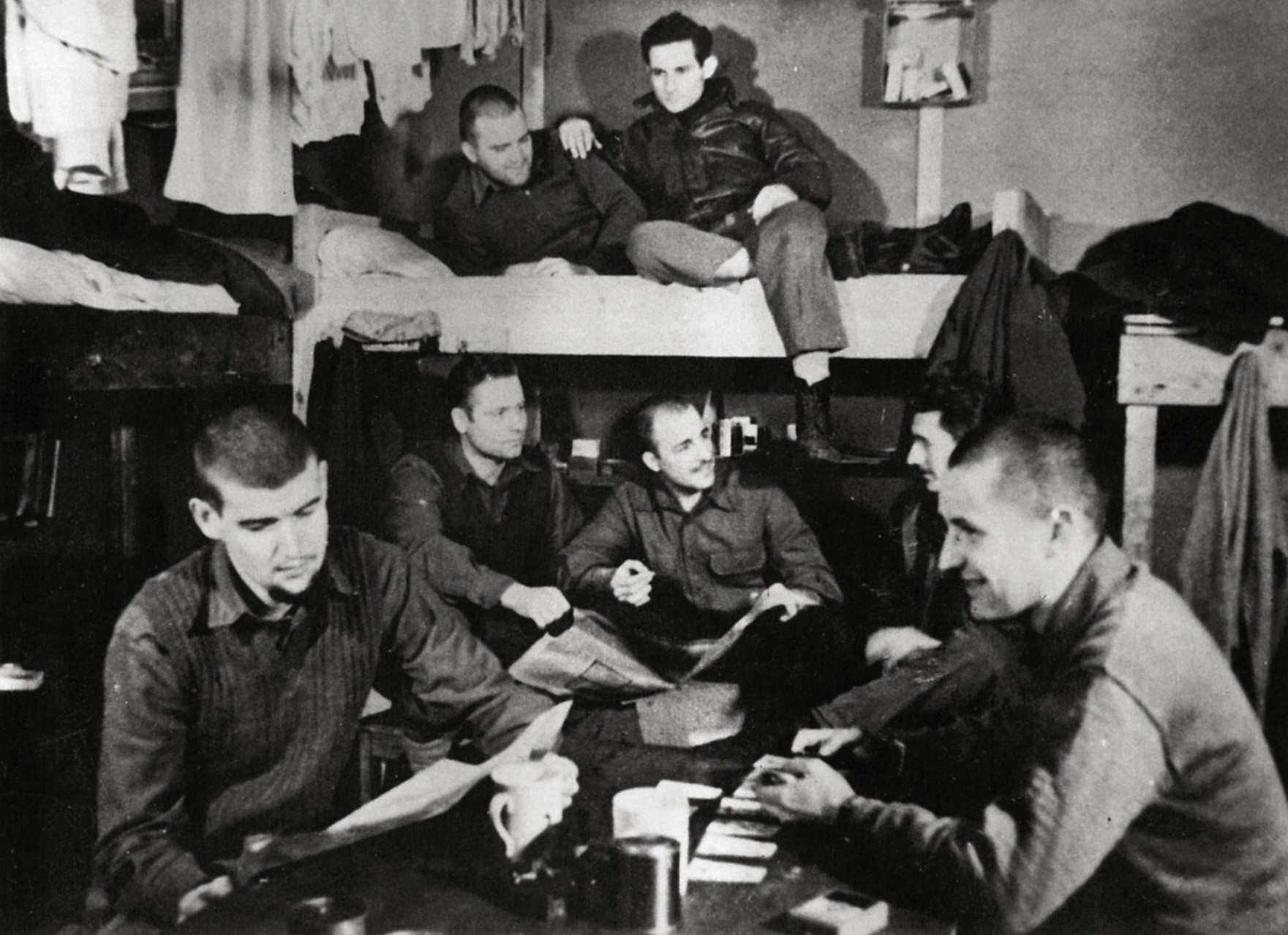

Located in Austria, Stalag 17 was originally established in 1939 to house POWs from Eastern Europe. By 1943, more than 64,000 French, Polish, Russian, Greek, and Serbian prisoners had passed through the camp. In the fall of that year, when the Eighth Air Force began taking heavy casualties on daylight raids deep into Germany, the first of several thousand young American airmen were transferred into a special section in the camp that was the responsibility of the Luftwaffe. The first “kriegies (an abbreviation of the German word for prisoner of war),” as the POWs referred to themselves, were a mixture of men who had been captured between 1942 and the summer of 1943. Their numbers grew again in the spring of 1944 when the Eighth Air Force returned to deep- penetration raids into Germany and again took heavy losses among its air crews.

Handy was an engineer/gunner on a B-24 crew with the 466th Bombardment Group. His crew was on the wing’s ninth mission when their Liberator was attacked by German fighters and so badly damaged that the pilot ordered the crew to bail out. Eight of the 10 crewmembers made it and two others were killed, either in the crash or after they reached the ground. After being rounded up by German soldiers and civilians, the 10 survivors were split up, with the officers going to their own camp while the enlisted men, including Handy, were sent to Stalag 17.

Handy and the other POWs arrived in a camp that they quickly learned was divided. The “Old Kriegies,” the men who had arrived at the camp several months before, set themselves apart from the newly shorn and deloused airmen who arrived in the spring—young men they resented because they were more recent arrivals in England. To the Old Kriegies, the new POWs were interlopers and slackers who had been living the easy life as they went through training in the United States before going overseas to enter combat. Yet Handy found a former schoolmate among the Old Kriegies on his very first day when two dirty and bedraggled POWs came to the new camp to check out the recent arrivals. When he visited his acquaintance the next day as instructed, he learned that his new quarters were in very close proximity to a storm drain that ran through the camp, a conduit that the Old Kriegie believed was his way out of the camp. Handy immediately went to work digging a tunnel that would serve as a sanctuary for POWs who had come to the attention of the Gestapo. During his incarceration, Handy worked on two tunnels, although neither was ever used for an escape.

It may come as a surprise to many readers that the Americans were generally well treated by their German guards, who considered them fellow airmen. The treatment of the American airmen was in stark contrast to that of the Russian POWs in the adjacent camp. While the United States was a signatory to the Geneva Convention for the treatment of prisoners, the Soviet Union was not. In the pecking order of the prison—which included British, French, Poles, and Slavs—the American airmen were at the top and the Russians were at the bottom.

While the story is about Handy’s experiences as a kriegie, interwoven into the narrative are accounts of his previous life, including anecdotes from his boyhood and previous military experience. He had come into the Air Corps by accident after originally enlisting for the Field Artillery, of which his father had been a part in World War I. In mid-1942, the War Department was building up the Army Air Forces and there was greater need for airmen than for artillerymen. His original assignment was as an aircraft mechanic in a maintenance squadron that took care of Consolidated B-24 Liberators at a training facility in Kansas. When he responded to a call for experienced mechanics to volunteer for aircrew duty, his supervisors encouraged him to withdraw the request. Handy refused. He later learned that his old outfit was converted into a remote maintenance squadron and sent to North Africa, where they were overrun by German forces.

There are some shocks in this work, particularly the callousness and cruelty with which the men of Patton’s 13th Armored Division treated the guards and local civilians when the kriegies were liberated at the end of the war. Even though the guards moved the airmen hundreds of miles west to prevent the Americans from falling into Soviet hands, the liberating soldiers fell on the guards after they surrendered and beat them to within an inch of their lives. Handy found himself defending Germans from marauding American soldiers, who were out to administer brutality to any German they came across.

The Flame Keepers is a truly outstanding book that provides an intimate look at the life of the POWs of Stalag 17.

Bataan: A Survivor’s Story, by Lieutenant Gene Boyt with David L. Burch, Foreword by Gregory J.W. Urwin, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2004, 272 pp., $27.95.

Bataan: A Survivor’s Story, by Lieutenant Gene Boyt with David L. Burch, Foreword by Gregory J.W. Urwin, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2004, 272 pp., $27.95.

On December 8, 1941, the late Gene Boyt (who passed away in 2003) was a 23-year-old first lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at Clark Field, Philippine Islands. Boyt’s war commenced when the first Japanese bombs fell on Clark Field, striking the bungalow (right off the main runway) he shared with three other officers just as the occupants were sitting down for their noon meal. One of his housemates was disemboweled by shrapnel and died within minutes. It was but the first of dozens of horrifying experiences Boyt would have over the next four years.

Written in collaboration with history teacher and Boyt family friend David Burch, Bataan is Boyt’s story, beginning with his childhood growing up in several locations from Missouri to Oklahoma to Arizona as his father moved around during the Depression The story continues through his education at the Missouri School of Mines, to his assignment in the Philippines, and through the war until he was finally repatriated at a remote camp in Japan. Boyt’s story is not just about the infamous Death March and the POW experience. A substantial portion of the narrative is related to his Philippines experience, both before the war and during the five months he spent at Clark and on Bataan before the American surrender. As an Army engineer, he was responsible for construction projects at Clark and Bataan, including the building of new runways at Clark Field to accommodate the B-17s that started to arrive in the Philippines in October 1941 and the construction of revetments to protect them from air attack. One of his projects was supervising the construction of decoy aircraft. Although the Japanese got lucky on the first day of the war when they caught the B-17s and a squadron of P-40s refueling on the ground after air patrols that morning, many of their bombs were actually directed at the decoys.

Before the war, Boyt worked under Colonel Wendel Fertig, a mining engineer and Army reservist who was called to active duty as the Americans began building up defenses in the Philippines. Fertig would escape to Mindanao from Corregidor, where he would organize and command a sizable resistance force. Boyt went into Bataan with a team of Filipino contractors and laborers. They joined the 803rd Engineering Battalion, an airfield construction unit, in building roads and airstrips. Boyt and other engineers developed elaborate ruses to decoy Japanese aircraft away from antiaircraft and artillery positions. They painted logs black (to give the appearance of gun positions) and set off dynamite charges to simulate artillery firing. In spite of their ingenuity and defiance before the Japanese, the days were numbered for the American and Filipino troops on Bataan. Inexplicably, when American forces were ordered to retreat to Bataan, they failed to bring adequate food supplies with them. Although there was plenty of ammunition, the men were soon on starvation rations, if they got rations at all. In spite of having inflicted heavy casualties among the attackers in the early weeks of the battle, the American forces were worn down by malnutrition and ill health. Surrender became their only option.

On April 9, 1942, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King surrendered his command on Bataan, believing it was the only logical thing to do. His men were worn down from hunger and the Japanese were rapidly advancing. Almost a month earlier, General Douglas MacArthur had been evacuated from Corregidor, leaving Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright in command of the forces in the Philippines, while King commanded the troops on Bataan. MacArthur’s orders to Wainwright and King were to hold at all costs, but King decided to disobey in the belief that it would save the lives of his men. Most Americans in his command had mixed emotions about surrendering. While they hoped for humane treatment, they had heard stories about Japanese atrocities in China and Singapore. Unfortunately, their worst fears would soon be realized.

In less than a week, thousands of American and Filipino soldiers would be dead at the hands of Japanese guards or of malnutrition and dysentery during the forced march from southern Bataan to Camp O’Donnell. Boyt credited his own survival to a bottle of iodine he managed to keep from the Japanese which allowed him to purify the putrid water and to a fellow POW’s effort to conceal him in the back of an empty truck driven by Filipinos after he was hit in the head by a passing Japanese soldier.

Unlike many of the Bataan survivors, Boyt did not remain in the Philippines. In October 1942, barely six months after the surrender of Bataan, he was part of a contingent of some 1,500 POWs who were transferred to Japan. Fortunately for them, the American submarine campaign against Japanese shipping was in its infancy, and although there were reports of a submarine sighting, the ship safely reached Japan. This could not be said of all of the POWs, however, as hundreds perished during the voyage due to the horrendous conditions under which they were held onboard ship. Boyt spent the rest of the war in camps in Japan.

The book is a well-written, interesting account of Boyt’s experiences that provides insight into the horrors suffered by American and Filipino prisoners at the hands of their Japanese captors.

Some Survived: An Eyewitness Account of the Bataan Death March and the Men Who Lived Through It, by Manny Lawton, with an introduction by John Toland, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 2004, 295 pp., $14.95.

Some Survived: An Eyewitness Account of the Bataan Death March and the Men Who Lived Through It, by Manny Lawton, with an introduction by John Toland, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 2004, 295 pp., $14.95.

Originally published in 1986, this is a re-release of Manny Lawton’s account of his experiences as a POW in the hands of the Japanese. Like Gene Boyt, Manny Lawton is now deceased, having passed away in 1986. Like Boyt, he survived the Bataan Death March and became a prisoner of the Japanese. Unlike Boyt, Manny Lawton remained in the Philippines for most of his captivity, until the frightened Japanese began moving their American POWs out of the islands as American forces advanced toward Luzon. Lawton was one of a group of POWs who were first sent to Japan, then were moved across the Yellow Sea to Korea and transported hundreds of miles to Jinson, later known as Inchon.

Reading Lawton’s and Boyt’s accounts of their imprisonment makes it obvious that all Bataan survivors were not treated the same, that there were degrees of suffering. Lawton was in a group of men who surrendered some 10 to 15 miles north of the southern tip of Bataan and thus were spared many of the treacherous miles of the trek that became a march of death. Most of those in Lawton’s group reached the railhead where they were loaded aboard the train to Camp O’Donnell in fairly good shape. There were some who died, such as the colonel who carried a barracks bag filled with food on the march and refused to throw it away. The additional burden caused him to fall farther and farther behind until an impatient guard finally killed him. Lawton relates the inhumanity of the POWs themselves. Contrary to popular assertions, everyone who serves in wartime is not a hero. Some are heels, and this is just as true of POWs as of anyone else. Quite a few Americans took advantage of their situation as members of work teams on projects outside the camp to obtain badly needed medical supplies and food, which they later sold to their fellow POWs at a large profit. Lawton himself was afflicted with a serious medical problem that he managed to survive only by giving a check for a substantial amount to one of the con artists for otherwise unobtainable food. Fortunately, the con man accepted the check.

Just as the assertion that all POWs were heroes is more myth than fact, so is the belief that inhumane actions by Japanese captors were universal. In fact, some Japanese offered acts of kindness or would look the other way when the POWs were doing something to make their lives easier, but which was against camp rules. This was particularly true of Japanese Christians. In one instance, the benevolence of a guard was rewarded with an escape attempt, an act that did not endear the attempted escapee to the other POWs, who lost one of the bright spots of their captivity as the benevolent guard was removed from the camp.

Lawton was a member of the contingent of POWs who were moved south from Camp O’Donnell to a new camp at Davao. There were successful escapes from the camp that were met with mixed emotions by the men who remained in Japanese hands. To many, the escapees were looked upon almost as traitors, since the Japanese would take out their frustrations on those who remained behind. Other officers and soldiers recognized that it was their military duty to attempt to escape. Japanese camp administrators reduced the number of escape attempts by threatening to kill 10 POWs for every escapee.

Thousands of POWs survived the horrors of the Bataan Death March and imprisonment only to lose their lives aboard ships, trucks, and trains as they were being transported from the camps in the Philippines to Japan and Korea. The terrible conditions on the ships accounted for many of the deaths, but large numbers perished from “friendly fire.” By 1944, when most of the prisoners were transported, the U.S. Navy had gained control of the Pacific Ocean and young American submarine crews made no attempt to determine the cargoes of any ships that came into periscope view. Many of the decrepit POW transports were sunk during the journey and thousands of POWs died at the hands of their fellow Americans.

Some Survived is perhaps one of the best books about the Bataan survivors’ experiences.

The World War II Desk Reference, Douglas Brinkley and Michael E. Haskew, editors, with The Eisenhower Center for American Studies, Grand Central Press, New York, 2004, 572 pp., $39.95.

The goal of the Grand Central Press team was to produce a concise volume of information about World War II that would serve as a ready reference for the student, scholar, or enthusiast. Although a number of encyclopedias and handbooks about the war have been published, until now there hasn’t been a single source of information where the interested reader could go to find specific information, such as the number of casualties experienced by the various combatant nations. The reader will find it in this volume. The information is arranged in short encyclopedic articles, tables, and columns. Significant subjects are covered in articles and sidebars. The text is supplemented by hundreds of photographs. High-quality maps help the reader to locate the cities, regions, nations, landmarks, and features related to the narrative.

As with anything, there are a few minor criticisms. Although major characters such as Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur are covered in detail, the articles for some important individuals are a bit lacking.

Seven Stars: The Okinawa Battle Diaries of Simon Bolivar Buckner and Joseph Stilwell, Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, editor, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2004, 224 pp., $29.95.

Seven Stars: The Okinawa Battle Diaries of Simon Bolivar Buckner and Joseph Stilwell, Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, editor, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2004, 224 pp., $29.95.

On April 1, 1945, Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s Tenth U.S. Army, which included the III Marine Amphibious Force, landed on the beaches opposite the Japanese airfields of Yomitan and Kadena on the Ryukuyan island of Okinawa. The landings were unopposed, and Marines moving northward into the rugged mountains met little resistance—the Japanese had elected to mount a fight-to-the-death defense of the southern part of the island, with their initial defense lines starting just east of the Okinawan city of Naha and the ancient castle at Shuri serving as a central defensive feature. As the American invaders made contact with the enemy’s outer defenses, the Japanese mounted a series of deadly air attacks against the hundreds of Allied naval vessels supporting the invasion. Many, but not all, of the attacking planes were flown by rudimentarily trained pilots who had been recruited to mount suicidal kamikaze attacks in outmoded combat aircraft and trainers. The Battle of Okinawa turned into a deadly slugging match.

As casualties during Okinawa mounted, the American media began questioning the leadership of the campaign. While the media questioning was public, many within the military also questioned Buckner’s competency as a commander. Although he wore three stars, Okinawa was Buckner’s first major battle. Meanwhile, General Joseph W. Stilwell had been fired from his position as the senior American officer in China. At the beginning of the war, Stilwell had been considered by some to be the U.S. Army’s “best general,” but the war had passed him by after he was sent to China to serve as the senior U.S. officer on Chiang Kai-shek’s staff. There was constant conflict between Stilwell, who believed that China’s internal struggles should be put on hold to defeat the Japanese, and Chiang, who recognized that the communist insurgency was as great a threat to China as the Japanese. Stilwell was frustrated by what he saw as a lack of commitment on the part of the Chinese, and he was not hesitant to criticize Chiang. The conflict finally came to a head in mid-1944. Stilwell was sent packing to the United States where he replaced General Leslie McNair, who had just been killed in Europe, as the commander of Army Ground Forces. As a senior U.S. Army officer with no troops to command, Stilwell convinced General of the Army George C. Marshall to allow him to go to the Pacific on an “inspection tour.” This was actually an effort to secure a field command for himself during the upcoming invasion of Japan. He quickly zeroed in on Buckner’s failings and began politicking to have himself appointed as the Tenth Army commander for the invasion.

As it turned out, Stilwell would replace Buckner after the Tenth Army commander was fatally struck by shrapnel from artillery fire while visiting a forward position. To some extent, Buckner was responsible for his own death. He frequently ignored the forward commanders’ requests that he conceal the trappings of his rank, which were easily visible to both U.S. front-line positions and to Japanese artillery observers. In fact, his front-line visits often brought enemy artillery fire to the outposts he had just visited.

Although U.S. Army regulations forbade the keeping of diaries, it was an order that both Buckner and Stilwell chose to ignore. Seven Stars is a juxtaposition of their two diaries, allowing the reader to compare the differences in the two officers’ style and manner of dealing with the problems of command. Stilwell’s diary is particularly interesting as it reveals the acid personality that gave him his nickname “Vinegar Joe.” He doesn’t hesitate to put on paper his criticisms of the various Allied leaders. Stilwell’s recordings of his thoughts during the hectic days prior to and following the Japanese surrender are particularly valuable.

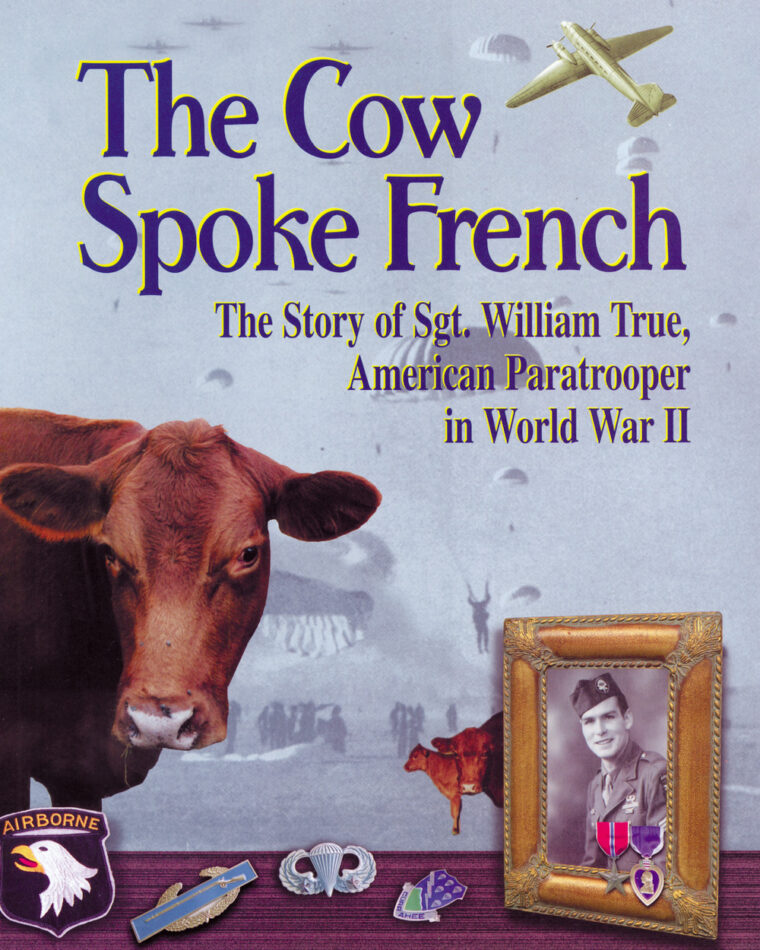

The Cow Spoke French: The Story of Sgt. William True, American Paratrooper in World War II, by William True and Deryck Tufts True, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2002, 180 pp., $34.95.

The Cow Spoke French: The Story of Sgt. William True, American Paratrooper in World War II, by William True and Deryck Tufts True, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2002, 180 pp., $34.95.

A collaboration between a father and his son, The Cow Spoke French follows the life of Bill True, a young Nebraska native living in California, from his enlistment in the paratroopers in the summer of 1942 through his return home at the end of the war. A member of F Company of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, True experienced the rigorous training at Toccoa, Georgia. It was this training that made the 506th unique, as they were the first airborne regiment to train as paratroopers from basic training.

The Trues take a somewhat unique approach to their writing task as the senior member of the team writes in first person, while his son fills out the narrative in the third person. Their book is also unique, in terms of books about paratroops, in that they include a chapter written from the perspective of the young troop carrier pilots and aircrews who flew the paratroopers into combat. After the war, Bill True became friends with Harold Wayne King, the pilot who dropped the stick on D-day, of which True was a part. The authors include an account written by King of his experiences with Douglas C-47 #849, from the time he and his crew picked it up at the factory in Fort Wayne, Indiana, until they surrendered it to a ferry crew when their group received Curtis C-46s to replace their war-weary C-47s in early 1945.

The Cow Spoke French is a well-written work that tells an honest tale of the experiences of a paratrooper in the ETO.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments