By Eric Niderost

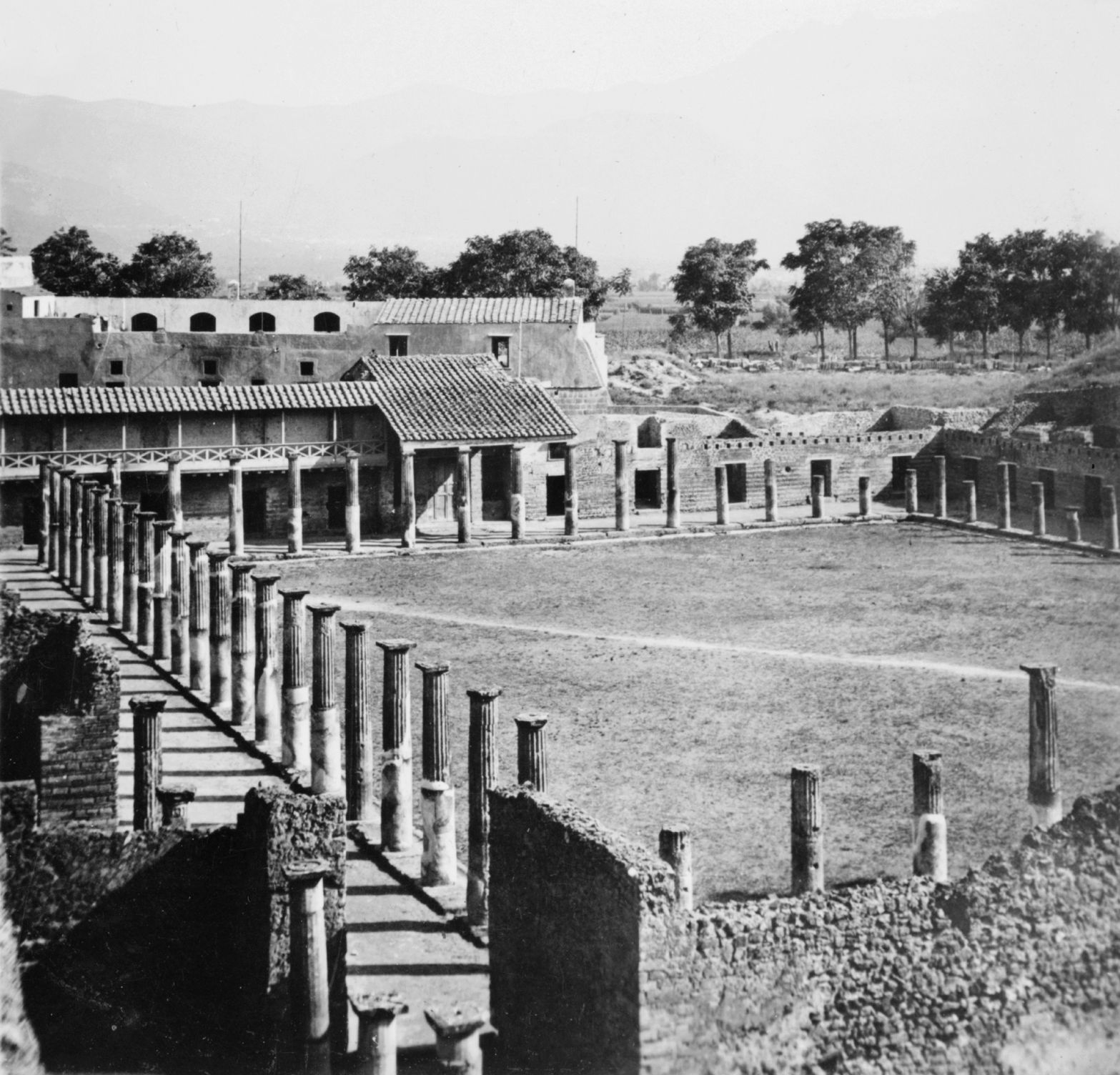

In the spring of 73 bc, Thracian gladiator Spartacus decided that the time was right to attempt an escape. He was a virtual captive at the gladiatorial school of Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Batiatus, located at Capua in the Campania region of southern Italy. Like most gladiatorial schools, the House of Batiatus was a combination barracks, fortress, and prison. There, gladiators such as Spartacus perfected a savage craft of hand-to-hand combat designed to entertain their Roman masters. The gladiators took their names from the short sword, or gladius, favored by many of the combatants. Some, like Spartacus, wielded curved scimitars called sica; others used long swords or tridents. All fought in gladiatorial “games” where life and death were decided by the direction of the crowd’s thumbs. Few expected mercy—most of the thumbs turned down, for death, at the end of a contest.

Spartacus wasn’t afraid of dying—as a warrior he scorned death—but he had grown tired of fighting and probably dying for the amusement of his casually brutal Roman captors. Spartacus was a Thracian, a member of the wild tribes that inhabited the region that is now Bulgaria. His real name was Spardakos, which translated as “famous for his spear.” He was about 30 years of age, and some have speculated he was of noble or aristocratic blood.

Spartacus was not born into slavery, but rather started his career as an auxiliary in the Roman Army. The legionary foot soldier was the backbone of Rome’s military forces, but other roles were provided by the auxilia (literally, “helpers.”) The Thracians, known as expert horsemen and superb cavalrymen, were particularly valued helpers. As a member of the Roman cavalry, Spartacus would have been close enough to observe and remember Roman strategy and tactics. He was a big man, bearded and physically imposing. The Thracians were feared as fierce warriors, with a reputation as hell-raisers not unlike that of the latter-day Vikings. They lived for battle and feasted with the severed heads of enemies decorating their dining halls.

Like many Thracian men, Spartacus sported tattoos that made him even more fearful. Yet beneath the barbarian surface was a man who could think, and think clearly. The Greek writer Plutarch declared that Spartacus “not only had great spirit and physical strength,” but was “most intelligent and cultured, being more like a Greek than a Thracian.” This was high praise indeed from a Greek.

For some reason, Spartacus deserted the Roman Army. Perhaps he wanted to join King Mithridates VI, as other Thracians had done. Mithridates was the ruler of Pontus, located on the southern shores of the Black Sea in modern-day Turkey. He had a powerful army, and his alliance with Cretan and Cilician pirates gave him command of the Black Sea, the Bosporus, and the eastern Mediterranean. Mithridates handily defeated Roman general Marcus Aurelius Cota, in part because the latter was a mediocre general. That was bad enough, but when Marcus Antonius, father of Mark Antony, took on the pirates, he was outmaneuvered and humiliated. Lucius Lucinius Lucullus, one of Rome’s best generals, hurried east to rectify the situation, but it was clear that the campaign would tie up the legions for some time to come.

Whatever the reason for his desertion, Spartacus was captured and sentenced to be a gladiator. In a way, he was lucky. He could have ended up nailed to a cross, as other deserters-turned-bandits had been. Instead, Spartacus became a heavyweight, or murmillo, gladiator, burdened with a staggering 35 to 40 pounds of arms and armor, including the well-known crested helmet. He certainly did not have to learn to fight. As soon as Spartacus entered the gladiator school, he made sure he got hold of a sica, the traditional weapon of a Thracian warrior. Its curved blade was deadly, and Spartacus was expert in its use.

Engineering a Slave Revolt

Discipline was harsh in the gladiatorial schools, and experienced soldiers such as Spartacus balked at the constant exercise, training, and dietary constraints. Punishment for even the slightest offense also chafed the gladiators. By the spring of 73 bc, Spartacus and others hatched an escape plan at Batiatus’s facility. For the breakout to be successful, Batiatus and his armed guards would have to be taken by surprise. It had to be a mass uprising as well, because an individual had little chance of success.

Unfortunately for the gladiators, someone betrayed the plot, and Spartacus’s hand was forced before the gladiators were ready. The guards moved in, but Spartacus and the others raced for the kitchen in a last-ditch quest for freedom. Once inside, they grabbed meat spits, cleavers, and anything else they could find to serve as weapons. A melee ensued that was brutal and bloody. Somehow, Spartacus and 74 others managed to escape into the countryside. By sheer good luck they intercepted a wagonload of weapons going to another gladiator school. Now better armed, they had to decide what to do next.

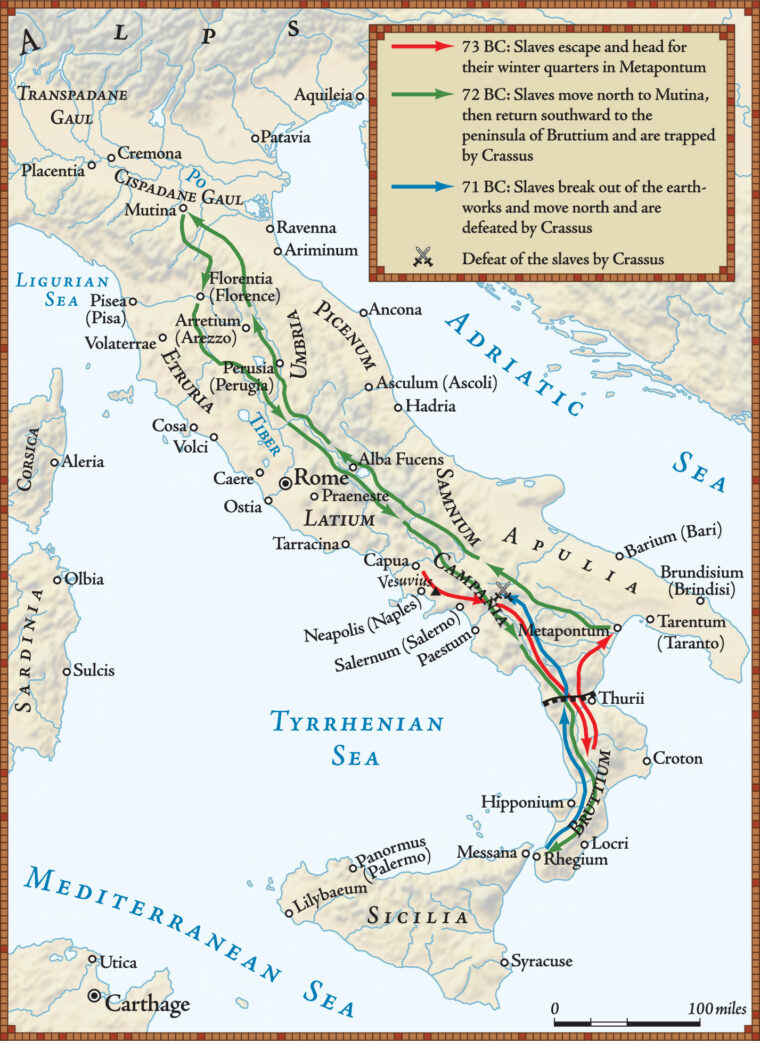

Freedom was not an end in itself; the fugitives wanted revenge for the humiliations they had endured at the hands of their Roman masters. Spartacus’s band included Thracians, Celts, and Germans, and it was natural that they wanted their own leaders. Spartacus led his countrymen, while Crixus headed the Celts, and Oenomaus became chief of the Germans. The unified rebels headed for Mount Vesuvius, some 20 miles away. The 4,000-foot-high volcanic peak had not exploded for centuries. The quiescent volcano afforded a good view of the surrounding countryside and was a natural fortress. Spartacus and his followers settled in to plan their next moves.

Slave revolts were nothing new in the Roman Empire. In 138 bc, several thousand ill-treated wretches rose up but were quickly crushed. In the aftermath of the rising, the survivors were crucified, 450 in Minturnae, 150 in Rome, and 4,000 in Sinuessa. Even more serious were the so-called Servile Wars in Sicily. In 135 bc and again in 104 bc, Sicilian slaves made a desperate bid for liberty but were defeated by the combined might of the Roman Empire.

But there was something different about Spartacus. Bold and charismatic, he welded the disparate elements into an effective fighting force—at least for a time. He was also fortunate in that Italy’s slave population was large and seemingly growing lager by the day. Rome was fast becoming the master of the Mediterranean, a juggernaut whose legions were the greatest military force in the world. In the first century bc, Rome’s dominions included North Africa, Greece, and parts of Asia Minor and Spain. Extensive conquests brought great wealth to the city on the Tiber, profoundly altering Roman society and politics in the bargain. Rome was the richest, most powerful, and most corrupt city in the world.

Rome was master of all it surveyed, but success came at an enormous social cost. In centuries past, the Roman legionary was a peasant soldier, but as Rome’s empire expanded, so did its armies. Legionaries found themselves fighting in the windswept mountains of Spain and the searing deserts of North Africa. When they did come home, they found their farms under threat from large landowners, many of them from the senatorial or business classes.

The process had begun as early as the Second Punic War (218-202 bc). The great Carthaginian general Hannibal had systematically laid waste to much of Etruria and southern Italy. Farmers were killed and records destroyed. As the decades passed and Rome’s wars of conquest continued, returning legionaries preferred the pilum (spear) to the plow and sold out to large landowners. Those who tried to continue farming found themselves under pressure to sell. Usually the large landholders won, and the farmers either retreated to marginal land or flocked to cities like Rome, where they became part of the new urban poor. Kept alive and relatively happy by public games and the government dole, the era of panem et circenis—bread and circuses—had begun.

By the beginning of the first century bc, most of the small farms were gone, replaced by large plantation-like estates called latifundia. Free peasant workers were replaced by slaves, chattel who were exempt from military service and were expected to work the year round. Slaves grew grain, olives, and fruit trees or tended sheep on large estates owned by a wealthy few. The slaves were mainly prisoners of war, although some were domestic slaves born in Italy. Slavery was big business and could reap huge profits for both buyer and seller. Sometimes, Romans even bought captives from pirates who sailed the Mediterranean like predatory sharks. The businessmen and wealthy magnates grew rich from the cheap labor of their human chattel, giving little thought that these same slaves might harbor a secret desire for freedom.

Soon Italy was awash with slaves—some two million in a population of only six million. There were so many slaves that the Roman Senate quickly rejected an idea that slaves wear some kind of distinctive garb. If the slaves realized how truly numerous they were, the senators reasoned, they might take it into their heads to revolt en masse. Spartacus’s breakout was perfectly timed even though the gladiators probably hadn’t given the matter much thought at the time. Rome was simultaneously bogged down in two costly wars on either end of the Mediterranean. The battle-tested, veteran legions were far away on campaign. With some exceptions, only second- or third-rate troops remained in Italy.

The runaway gladiators had a unique opportunity to take revenge on their former Roman masters. Now that they were safely ensconced in Vesuvius’s crater, the fugitives could forage and plunder at will. The countryside was rich, garlanded with grapes that grew on thick vines nourished by the volcanic soil. Food was was plentiful, and nearby patrician estates were ripe for plunder. Spartacus gained more and more recruits. Most were runaway slaves, but others were simply disaffected farmers. Soon there were several thousand rebels camped out on Vesuvius, the beginnings of a small army. Roman authorities were slow to react. Spartacus and his band of rebels were so small in number at first that they seemed little better than the other roving bandits who infested the country roads of Italy. A group of Capuan policemen—armed men probably hired by Batiatus—began tracking the gladiators, but they soon got more than they bargained for. The Capuans were easily sent packing, but they left behind good weapons and armor. From their base on Vesuvius, the rebels raided the rich, lush countryside, terrorizing landowners. Back in Rome, news filtered in about Spartacus’s escape and the plundering of the local countryside. The Senate decided to send one of its praetors, or magistrates, Gaius Claudius Glaber, to deal with the situation. There were eight praetors in all, and most of them were ambitious men. On the other hand, slave catching was not considered the most glorious of occupations.

Glaber accepted the assignment and rounded up some men. In its wisdom, the Senate had decided to characterize the gladiator breakout as a tumultus—an emergency. It was a serious matter, but not as serious as a war. There were few real soldiers available, so Glaber fell back on the time-honored expedience of recruiting from the countryside as he marched south. The retired veterans in the vicinity looked upon slave catching with such distaste that few would volunteer. Glaber somehow managed to gather some 3,000 men, raw recruits who were essentially militia, not soldiers. They were well armed and well equipped—much to Spartacus’s later delight—but it was all a showy façade.

Glaber arrived at the foot of the volcano and considered his options. There was only one road up to the summit, and it was narrow and twisting. Glaber was no Hannibal, but even he recognized that the slaves held the high ground. The praetor decided to blockade the fugitives and starve them out. The Romans made camp at the base of the volcano and put a heavy guard on the road. Spartacus and his rebels were bottled up—or so it seemed.

Not wanting to be held hostage on his own turf, Spartacus decided to take the offensive. His men made ropes of the wild grapevines that carpeted the area. Scouting his position, Spartacus saw that one side of Vesuvius had been left unguarded because the Romans saw it as fairly steep and the surrounding soil as unstable. The vine ropes could be lowered down, thus providing a kind of natural banister that the men could hold onto as they descended. Once all of Spartacus’s men were safely down the mountainside, he led them in an attack on the Roman camp. Caught literally napping, the Roman soldiers had little chance, especially against expert warriors who reveled in hand-to-hand fighting. Most of the Romans simply fled in panic, abandoning their camp and leaving behind a great store of weapons, armor, food, and plunder to the triumphant rebels.

The Competing Strategies of Spartacus and Crixus

The Senate heard of Glaber’s defeat with a mixture of irritation and concern. Praetor Publius Varinius was dispatched to take on the slaves, with his colleague Lucius Cossinius marching in support. Once again, raw troops were gathered along the way, with predicable results. Cossinius was defeated and killed near the baths at Herculaneum, and several detachments led by Varinius’s subordinates also met with disaster near Vesuvius. Varinius still remained in the field, but it was beginning to look like he was in over his head.

Yet rebel successes were causing dissension in their ranks. Spartacus wanted to march north and leave Italy for good. Most of Gaul and parts of Thrace were still free. Passing through the Alps wouldn’t be easy, but if Hannibal had done it 150 years earlier, so could they. In any case, staying in Italy was tantamount to suicide. Sooner or later, the Roman legions—real, battle-tested, veteran legions—would return, and the rebels would be destroyed. The Celtic leader Crixus disagreed. Overconfident, he wanted to attack Varinius. To him, heading north without battle was tantamount to turning tail. Crixus and many of the slaves wanted to keep raiding Roman farms and country estates. Riches were theirs for the taking. The gleam of gold blinded them to the real dangers that confronted them.

Finally a compromise was reached. The gladiators would stay in Italy, at least for the time being, and they would fight Varinius. But Spartacus insisted that their insurgent army was not yet ready to tackle the praetor. The Thracian would lead them south, to open pastureland, where they would gather and train more recruits. They would be heading away from the Alps and safety, but there was method in Spartacus’s madness. The vast pasturelands were where slave shepherds tended flocks. The shepherds were tough, hardy, and independent, and they were used to fighting wild animals and occasionally brigands. With proper weapons and training, they could be molded into the backbone of the insurgent force.

As the gladiators marched south, thousands flocked to Spartacus’s banner. When the time was right, they turned on Varinius at Lucania. The Romans were routed, and Varinius barely escaped with his life. Worse still, the rebels captured the bundles of rods and axes, called fasces, which were the symbols of a Roman magistrate’s power and, by extension, of Rome itself. After this victory, thousands more slaves joined Spartacus’s army, some of them still carrying their chains. The insurgent army now numbered 40,000 men and a vast number of women and children who were camp followers.

Spartacus took the winter of 73-72 bc to manufacture weapons and train men. Now that the Romans had been taken care of—at least for the moment—Spartacus once again turned his thoughts northward. He would cross the Apennines and march along the Adriatic Coast toward the Alps. As before, the ultimate goal for the insurgents was to leave Italy and return to their far-flung homes.

The Romans awoke at last to the gravity of the situation and put Consuls Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus into the field. The rebels played into Roman hands by splitting up their forces. Crixus took around 10,000 men—perhaps more—and separated from Spartacus. Gellius caught up with Crixus near Mount Garganus and crushed him. Two-thirds of the insurgents, including Crixus, were killed in the debacle.

Spartacus, meanwhile, headed north, liberating slaves in the towns of Consentia and Metapontum and adding to his strength. Any freed slaves who wanted to join his army received weapons and rudimentary training on the march. In separate encounters with the pursuing Roman consuls, Spartacus managed to badly defeat both Gellius and Lentulus. The consuls retreated, but there was still a piece of unfinished business left to complete. Spartacus honored the slain Crixus by forcing 300 Roman prisoners to fight to the death near a symbolic funeral pyre. Even the most illiterate slave appreciated the irony: now the Romans were the gladiators and the slaves were the spectators.

Once the games were over, it was time to resume the march north. There was another brief encounter with the consuls, but they were brushed aside and the march resumed. There was one more hurdle for Spartacus to clear: Proconsul Gaius Cassius Longinus, governor of Cisalpine Gaul, and his garrison at Mutina. Cisalpine Gaul was the northernmost province of Italy, centered in the Po valley. Cassius, the father of Julius Caesar’s future murderer, had two legions—some 10,000 men—at his disposal. It did him no good. In the end, Cassius was mauled by Spartacus’s army, and the proconsul barely escaped with his life. The road though the Alps was open and beckoning. Spartacus urged his men to escape Italy at last, but most refused. Grandiose dreams still filled their minds and fevered their imaginations. Much of Italy lay defenseless and ripe for plunder. Some even talked wildly of taking Rome. Probably a few did escape over the mountains and returned home, but the others turned south once again.

In theory, the road to Rome was open, but Spartacus refused to rise to the bait. Rome was smaller than its later Imperial incarnation. Great monuments such as the Coliseum and the Pantheon were yet to be built. Nevertheless, Rome was still a sizable city, with seven miles of walls enclosing 1,000 acres. Some of the walls reached heights of 13 feet. The walls had defied Hannibal, one of the greatest military geniuses of all time. Could Spartacus, untrained in the art of siege craft and lacking engineers, do better?

Spartacus probably never seriously considered trying to take the city, although he may have rendered lip service to his followers. The thing to do was to push south, into the lush and welcoming fields of southern Italy. In the autumn of 72, he and his insurgent army were still at large, and from the Roman point of view there was no end in sight. What was needed was a fresh approach, implemented by a new commander untainted by the stench of recent defeats. The Senate turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus. He was one of the richest men in Rome, with a fortune reckoned at 170,000,000 sesterces.

With money no object, Crassus easily raised six new legions. Thanks to his previous service under the great Roman general Sulla, he had a good reputation as a military man, and retired veterans responded eagerly to his call to arms. In addition to the newly raised legions, Crassus had the remnants of the consular forces recently defeated by Spartacus. In all, Crassus’s army totaled about 45,000 effectives. By contrast, Spartacus was at the peak of his power and fame, with somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000 men at his disposal. Most Romans had contempt for slaves, even after the insurgent victories, but Crassus wasn’t going to fall into that trap. The remains of the consul legions were posted around Ancona in the south. Crassus ordered his subordinate Mummius to shadow Spartacus, but not to engage in battle.

Mummius, seeking glory, disobeyed the orders and fought the wily Thracian with predicable results at Picenum, on the central Adriatic coast. The Romans were not only routed, but some literally threw away their weapons in panic as they ran. This was the ultimate disgrace in the ancient world. Crassus knew that he had to do something—and fast—to stop the contagion of fear from spreading through his new legions. He turned to an ancient method that had fallen out of favor in recent years—decimation. He chose 500 of the runaways who had disgraced themselves by flight and divided them into 50 groups of 10 men each. One man from each group was chosen by lot to be beaten to death by his comrades. This was harsh even by Roman standards, but soon the legionaries feared their commander more than they feared Spartacus.

In the winter of 72-71 bc, Spartacus’s army arrived in Bruttium, in the toe of Italy, and took the city of Thurii. His intention was to cross over to Sicily, but what he intended beyond that is mere speculation. Spartacus may have wanted to establish a freed slave kingdom on the island. Sicily had a history of slave rebellion, and the thousands of still-discontented human chattels would welcome his arrival. Another line of thought involved the Cilician pirates. They might ferry him across the strait to Sicily or be persuaded to transport his men back to their homes, or at least to territory not held by the Romans. If Spartacus took Sicily, he could use the island as a naval base of sorts.

Something went wrong, however, and the pirates never showed up. (Crassus may have bought them off, or else they simply betrayed Spartacus on their own.) With their disappearance, Spartacus was trapped when Crassus showed up and cut him off in the peninsula forming Italy’s toe. Crassus ordered his men to build a wall across Bruttium, from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Ionia Sea, a distance of about 35 miles. The Roman fortifications were not continuous, but they were formidable. There was a stone wall at least 25 feet high, a wooden palisade, and a trench that was spiked by wooden stakes. Spartacus’s first attempt at a breakout ended in defeat. Things looked grim for the formerly triumphant rebels.

It was now the winter of 71 bc, and supplies and tempers were growing shorter by the day. The Italian toe region was a cold, sparse land with little food and less comfort. Rebel morale began to plummet faster than the temperatures. Spartacus had his own antidote to such gloom. According to ancient writers, he crucified a Roman prisoner in no-man’s-land between the two armies to demonstrate to his own troops the fate awaiting them if they were defeated. It was a salutary lesson. Crucifixion had no religious meaning in the first century—it was simply the most painful and degrading death the ancient world could conceive. Spartacus’s men knew that crucifixion would be their fate if they were captured alive. They crucified a Roman in full view of his fellow legionaries.

Spartacus was not going to end up on the cross if he could help it. He devised a bold plan to escape the trap, but he needed the proper weather conditions. Sometime in February, Spartacus made his move. He struck the Roman fortifications in the very teeth of a howling snowstorm, filling in the Roman defensive trench with earth, wood, branches, and the half-frozen corpses of slain prisoners. The bulk of the insurgent army escaped, but the rebels were still an undisciplined force, content to follow a leader only as long as he gave them victory and plunder. Spartacus had gotten them out of the trap, but his aborted Sicilian scheme had nearly led to disaster.

The Defeat of Spartacus

A large group of rebels, led by Castus and Gannicus, split off from Spartacus. Eventually, Crassus caught up with the splinter group and crushed it at Lake Lucania. Many chose death rather than surrender. Some 12,000 rebels, including the leaders, met their end. Spartacus and his remaining men—perhaps 35,000 or so—were still at large, but it was the beginning of the end. The wily Thracian managed another victory against two of Crassus’s subordinates, but the final outcome was never in doubt. In the last weeks, Spartacus’s movements were more like those of a hunted animal than an independent commander.

The main rebel army was finally cornered between two Roman armies near Apulia in April 71. Crassus led one force; Lucius Lucullus landed at Brundisium with another. Spartacus knew that the odds against a victory were astronomical, but he was determined to see it through to the end. As a gesture of defiance, he killed his own horse before the battle. He would fight on foot like the majority of his men. If they won, they would get new horses; if they lost, it wouldn’t matter anyway.

Spartacus tried to reach Crassus in an effort to personally kill his rival. Observers saw Spartacus personally kill two Roman centurions as he pushed through the melee toward Crassus. As he flailed away, his sica coated in crimson, the gladiator got close enough to catch sight of Crassus, wounded in several places, before he finally dropped to his knees. Drenched in sweat and blood—his own and the enemy’s—Spartacus continued to fight from a prone position before being overwhelmed. His body was so hacked to pieces that it was never recovered or identified.

The rest of the slave army was similarly annihilated. After two years, the Spartacus Revolt was over. Triumphant at last, Crassus was determined to exact a terrible punishment on the thousands of rebel prisoners who had survived. All 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way from Capua to Rome, a forest of crosses bearing bitter human fruit. Death was painful and lingering, and after death the bodies were allowed to decay in place. The horror and stench lingered for months.

Spartacus was dead, but he was not forgotten. Over time, his legend grew, a vivid tale that resonated through the centuries. The real Spartacus has been replaced by one motivated by a political agenda. There is no evidence that he was a social revolutionary who wanted freedom and justice for all. He certainly wanted liberty for himself and his followers, but he probably wasn’t interested in completely overturning a social order that was still seen as natural in most ancient societies. But whatever his ultimate motives, Spartacus was an exceptional man, one whose courage and charisma shook the Roman Empire to its very foundations.

A quick comment about gladiators.

Gladiators were paid fighters, a combination of slaves, prisoners, and volunteers who agreed to a contractual term of service. They were not generally expected to die in the arena, they were too valuable. Julius Caesar, at one point, owned a school of some 300 gladiators. Spectators bet on the fights, and owners of schools made a lot of money.

Gladiators who were especially good fighters were sometimes pardoned or freed at the end of the fight. Gladiators were generally freed at the end of their contract, usually 30-35 fights. Many of them became guards for public figures and, what we might call bouncers or police, guarding public places, They were widely respected as proven fighters.

There are lot of myths and legends about gladiators, mostly hearsay. There is only one written account of a gladiatorial match, that of Varus and Priscus is AD 80. They fought to a draw with such gallantry and skill that they were both pardoned at the end. A unique result.

A bit of an aside. Contrary to the movie Ben Hur, Romans did not have galley slaves. Again, in the roman system slaves were too valuable to be wasted as cheap labor. Roman soldiers rowed their own ships. In one account, Julius Caesar needed to race back to Rome from Spain for an election. He, along with every other man on the ship, rowed constantly for eight days in 4-hour shifts. They made it in time.

I generally find real history to be more fascinating than the myths and legends.